C&C 40 Still Turning Heads

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Make Handy Boat Your Home Port in 2012 Fuel, Ice, Supplies Stop by Our New Marine Facilities Gasoline & Diesel to Discuss Your Boating Needs

Maine Yacht Racing 2012 The offiicall Yearbook of the Guullf of Maiine Ocean Raciing Associiatiion www.gmora.org !!"## $ %& '( ' )!' )%$ HANDY BOAT SERVICE A Full Service Boatyard Boat Storage Painting & Gelcoat Yacht Rigging Fiberglass Repair Re-Powering Launch Service Moorings Make Handy Boat your home port in 2012 Fuel, Ice, Supplies Stop by our new marine facilities Gasoline & Diesel to discuss your boating needs. Mechanical Repairs Join us at the new Falmouth Sea Grill. Custom Wood Work 215 Foreside Rd. Falmouth, ME 04105 (207) 781-5110 www.handyboat.com 2 www.gmora.org Maine Yacht Racing She’s Taken You To Bermuda, The Caribbean And The Bras d’Or Lakes. Perhaps It’s Time You Took Her To Morris. MorrisCare. The Refit, Refined. Let MorrisCare take your expectations for ser vice some of the world’s most admired yachts. to a completely new level. At Morris there is no job On top of that, our yards in Northeast Harbor and we haven’t seen before and no special fabrication Bass Harbor are situated in the heart of Maine’s most beyond our capabilities. Whether we troubleshoot dramatic cruising grounds. Penobscot Bay, Blue Hill Bay, a small electrical problem and send you on your offshore islands and Acadia National Park are all right way or undertake a major refit, you’ll quickly at our doorstep. A rewarding destination unto itself. see the difference Morris service Don’t you think your boat deserves a people make. trip to Morris? Maybe you should come to That means you can plan to repaint, our doorstep as well. -

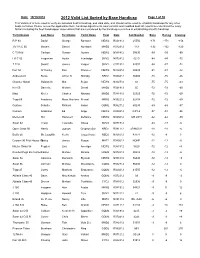

2012 Valid List Sorted by Base Handicap

Date: 10/19/2012 2012 Valid List Sorted by Base Handicap Page 1 of 30 This Valid List is to be used to verify an individual boat's handicap, and valid date, and should not be used to establish handicaps for any other boats not listed. Please review the appilication form, handicap adjustments, boat variants and modified boat list reports to understand the many factors including the fleet handicapper observations that are considered by the handicap committee in establishing a boat's handicap Yacht Design Last Name First Name Yacht Name Fleet Date Sail Number Base Racing Cruising R P 90 David George Rambler NEW2 R021912 25556 -171 -171 -156 J/V I R C 66 Meyers Daniel Numbers MHD2 R012912 119 -132 -132 -120 C T M 66 Carlson Gustav Aurora NEW2 N081412 50095 -99 -99 -90 I R C 52 Fragomen Austin Interlodge SMV2 N072412 5210 -84 -84 -72 T P 52 Swartz James Vesper SMV2 C071912 52007 -84 -87 -72 Farr 50 O' Hanley Ron Privateer NEW2 N072412 50009 -81 -81 -72 Andrews 68 Burke Arthur D Shindig NBD2 R060412 55655 -75 -75 -66 Chantier Naval Goldsmith Mat Sejaa NEW2 N042712 03 -75 -75 -63 Ker 55 Damelio Michael Denali MHD2 R031912 55 -72 -72 -60 Maxi Kiefer Charles Nirvana MHD2 R041812 32323 -72 -72 -60 Tripp 65 Academy Mass Maritime Prevail MRN2 N032212 62408 -72 -72 -60 Custom Schotte Richard Isobel GOM2 R062712 60295 -69 -69 -57 Custom Anderson Ed Angel NEW2 R020312 CAY-2 -57 -51 -36 Merlen 49 Hill Hammett Defiance NEW2 N020812 IVB 4915 -42 -42 -30 Swan 62 Tharp Twanette Glisse SMV2 N071912 -24 -18 -6 Open Class 50 Harris Joseph Gryphon Soloz NBD2 -

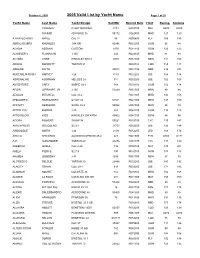

Valid List by Design

Date: 10/19/2012 2012 Valid List by Design, Adjustments Page 1 of 31 This Valid List is to be used to verify an individual boat's handicap, and valid date, and should not be used to establish handicaps for any other boats not listed. Please review the appilication form, handicap adjustments, boat variants and modified boat list reports to understand the many factors including the fleet handicapper observations that are considered by the handicap committee in establishing a boat's handicap. Design Last Name Yacht Name Record Date Base LP Adj Spin Rig Prop Rec Misc Race Cruise 1 D35 Schimenti Zefiro Toma R043012 36 -9 -3 24 42 12 Metre Gregory Valiant R071212 3 +6 9 9 12 Metre Mc Millen 111 Onawa R011512 33 -6 27 33 5.5 Carney Lyric R082912 156 u156 u165 8 Metre Palm Quest N071612 111 111 117 Aerodyne 38 D' Alessandro Alexis R053112 39 39 48 Akilaria Class 40 Davis Amhas R072312 -9 -9 -3 Akilaria Class 40 Dreese Toothface R041012 -9 -9 0 Alben 54 Ketch Wiseman Legacy V R070212 57 +6 +6 69 78 Alberg 35 Prefontaine Helios R042312 201 -3 198 210 Alberg 37 Mintz L' Amarre R061612 156 +6 +3 +6 171 186 Albin Cumulus Droste Cumulus 3 R030412 189 189 204 Albin Nimbus 42 Pomfret Anne R052212 99 99 111 Alden 42 S D S M Vieira Cadence R011312 120 +6 +6 132 144 Alden 44 Rice Pilgrim N053112 111 +9 +6 126 141 Alden 44 Weisman Nostos R011312 111 +9 +6 126 132 Alden 45 Davin Querence R071912 87 +9 +6 102 108 Alden 45" Seagoer Dunne Cygnet N040212 141 141 147 Alerion 26 Lurie Mischief R040612 225 U225 U231 Alerion Express 28 Brown Lumen Solare C082212 -

YACHT SALES & CHARTERS Contact Scott Blake in Bellingham Or Ken Bowles in Seattle at 206.554.1642 for All Your Brokerage Needs

OCEAN ALEXANDER !R() *)+?>7$" :R@9)< 0'7$" /6'9'/,#$.#%$:#!! ?(2 @8#!!#3%$# Gh tr Tryrpv s Ir H `hpu Dr ur Xr 8h :R() *)+?>7$! :$R;')<= ')67!" 3.R 9) 2 (97$$ 3R 9)6?>7$% )9,0#$3#".#$" 6 '8(9#$.#"$!#%.. /6'9'/,#$.#%$:#!! )9,0#$3#".#$" 3R() *)+67$3 3$R 9) 2 (97$: 3R )96+'7$% ."R>(2427!:" 6 '8(9#$.#"$!#%.. /6'9'/,#$.#%$:#!! (2 #!!#":$#" ?(2 @8#!!#3%$# ."R() *)+67$ ."R() *)+67$3 .3R() *)+67!"3 ..R() *)+."67$ )9,0#$3#".#$" /6'9'/,#$.#%$:#!! (2 #!!#":$#" ?(2 @8#!!#3%$# ..R)(9 / 7$3 ..R,0')67$. .%R 9) +67$ .%R67$ )9,0#$3#".#$" ?(2 @8#!!#3%$# )9,0#$3#".#$" ?(2 @8#!!#3%$# .$R'+(<7$: A$B.$R() *)+67!! .$R1/ )67$ .R() *)+ (('7$3 6 '8(9#$.#"$!#%.. ;)60#$3#$:# 6 '8(9#$.#"$!#%.. /6'9'/,#$.#%$:#!! !"! $.. '/$$0'1(2!$33% #"#$#%" #"#!#%.. &'() *)+&(', &'() *)+&(', -'() *)+&(', 4')-'() *)+&(', & $Q` %:%RV`R:CV R R JJ:]QC1R R V:CV R R Q% .:I] QJU^_ % `:C1:LV1V:C:JRU " :JG%CU .79!#(4).'!02), SECOND ANNUAL ( * + ( N% - . ! / 011)% & [ 2 ( !! 34 $ ( ! R 80+BOATS [ ! "# $ % % & ' ( ! )#[ ! ON DISPLAY /( * [ '% & 5 6 $ 7)R038R - ! R""R94R . : ! $ ! [ ! ! : (! 5 ( ; * [ MAY 5 ( 2 5 (/ <.! ( . !! 0)# ( $ ( ( ! < =>! R : \ ( 20-22 ! ( ( R ( =>! &' [ ( R FRI•SAT•SUN 12 PM-7 PM 5! [ ' 2 ' = = > ( * + ##R7#R<9#R 5 !( : ( -

2011 Valid List by Design, Adjustments

Date: 10/04/2011 2011 Valid List by Design, Adjustments Page 1 of 34 This Valid List is to be used to verify an individual boat's handicap, and valid date, and should not be used to establish handicaps for any other boats not listed. Please review the appilication form, handicap adjustments, boat variants and modified boat list reports to understand the many factors including the fleet handicapper observations that are considered by the handicap committee in establishing a boat's handicap. Design Last Name Yacht Name Record Date Base LP Adj Spin Rig Prop Rec Misc Race Cruise Pomfret Anne R033111 99 +9 108 108 Schoeder Dakota R041211 144 +6 U150 U159 1 D35 Schimenti Zefiro Toma N072611 36 -9 -3 24 42 12 Metre Gregory Valiant R062411 3 3 9 12 Metre Marshall American Eagle N061711 24 24 36 12 Metre Mc Millen 111 Onawa R012811 33 -6 27 33 30 Sq Metre Kilvert Cythera R040111 138 U138 U147 Advance 33 Delaney Ardent N071811 150 150 159 Aerodyne 38 D' Alessandro Alexis R041011 39 39 48 Akilaria Class 40 Davis Amhas R061511 -9 -9 -3 Akilaria Class 40 Dreese Toothface R040511 -9 -9 0 Alberg 35 Krakoff Caper N081511 201 +3 +6 210 225 Alberg 35 Prefontaine Helios R041211 201 -3 198 210 Alberg 37 Case Thisbe N052211 162 +3 165 177 Alberg 37 Kuhl Kemo Sabe R051011 162 +3 165 177 Albin Cumulus Droste Cumulus 3 R030411 189 189 204 Albin Nimbus 42 Nelson Slora Bjomen C091211 99 +9 +6 114 120 Alden 40 Burt, Jr. Gitana R041311 171 171 177 Alden 42 S D S M Vieira Cadence R042011 120 +6 +6 132 144 Alden 44 Flores Checkmate N062811 111 111 123 Alden 45 Davin -

Swiftsure International Yacht Race 2010 Presented By: Royal Victoria Yacht Club Official Results

Swiftsure International Yacht Race 2010 Presented by: Royal Victoria Yacht Club Official Results Place in Place in Place in Rnd. Place Sail Elap. Rnd Corr. Elapsed Finish Elap. Fin Corr. Elapsed Div Status Division Class Race in Division Number Yacht Name Make Skipper Yacht Club Rating Time Rounding Time Time Time Finish Time Swiftsure Lightship Classic Class: 1 A Finished 1 1 1 3 CAN54500 Strum Riptide 50 MacDonald, Ross RVanYC -54 11:45:00 13:50:42 30 13:23:02 27:23:02 29:28:44 A Finished 2 2 2 1 69189 Icon Perry 66 Welch, Kevin Anacortes -69 9:58:12 12:38:49 30 13:12:08 27:12:08 29:52:45 A Finished 3 3 3 2 USA 66 Neptune's Car Santa Cruz 70 , CYCSeattle -66 10:46:28 13:20:06 30 13:22:27 27:22:27 29:56:05 A Finished 4 4 4 4 28852 Marda Gras santa cruz Phelps, Marda Seattle -6 14:39:00 14:52:58 30 15:46:03 29:46:03 30:00:01 A Finished 5 10 10 5 18 Jam J/160 McPhail, John GigHbr -6 15:05:00 15:18:58 30 17:46:10 31:46:10 32:00:08 A Finished 6 11 11 6 69830 Rage Wylie Rander, Steve & Nancy RVicYC -36 14:41:00 16:04:48 30 16:40:52 30:40:52 32:04:40 B Finished 1 6 6 2 3801 Kairos Aerodyne Jewula, Ron RVicYC 45 16:15:20 14:30:35 30 18:26:35 32:26:35 30:41:50 B Finished 2 9 9 1 59902 Terremoto Riptide 35 Burbank, Scott Slooptvrn 39 15:58:37 14:27:50 30 19:04:49 33:04:49 31:34:02 B Finished 3 12 12 3 59494 Night Runner Perry Fryer, Doug Anacortes 75 18:34:36 15:40:01 30 21:13:37 35:13:37 32:19:02 B DNF - - - - 74427 Red Sheilla Beneteau Innes, Jim Waikiki 57 - - n/a - - B DNF - - - - 46724 Electre Beneteau 45F5 Bishop, George Nanaimo 72 18:20:29 -

INSTALLATION LISTING * Denotes Installation Drawing Available Configuration May Be Boat-Dependent

INSTALLATION LISTING * Denotes installation drawing available Configuration may be boat-dependent BOAT MODEL SHAFT BRACKETS 7 Seas Sailer 37.5 ft ketch* M HE Able 42* M+5 HE Acadian 30* M HE Acapulco 40 (Islander) L HE Accent 28 S HE Accord 36 M HH Achilles 24 S HE Achilles 840 M EH Achilles 9m M EH Adams 35* M EH Adams 40 M HE Adams 45 M EH Adams 45/12.7T* X HH Afrodita 2 1/2 (Cal 2‐46)* X HE Alaska 42 L EH Alberg 29* M HE Alberg 30 M HE Alberg 34* M HE Alberg 35 S HE Alberg 37* M HE Albin Ballad* M EH Albin Vega* S HE Alden 42 yawl* S HA Alden 45/51* X HA Alden 50* X HE Alden 50* X+5 HA Alden Challenger 39* M HA Allegro 33 ‐ off center M HH Allen Pape 43* L HE Allied mistress MK III 42 ketch L HE Allied Princess* L HH Allied Seawind 32 Ketch* M HE Allures 45 S AH Älo 33* M EH Aloha 28* S EH Aloha 30* M EH Alpa 11.5* M EH Alubaat Ovni 495 S‐10 AH Aluboot BV L EH Aluminium 48 X HH Aluminum Peterson 44 racer X AH Amazon 37 L HA Amazon 37* L HE Amel 48 ketch X EH Amel 54 L AH Amel Euros 39* L HE Amel Euros 41* L HH Amel Mango* L HA Amel Maramu 46 and 48* L HH Amel Santorin X EH Amel Santorin 46 Ketch* L EH Amel Sharki 39 L EH Amel Sharki 39 M EH Amel Sharki 40 L EH Amel Sharki* L EH Amor 40* L HE Amphitrite 43/12T* X+15 HA Angleman Ketch* L HE Ankh 44* M HE Apache 41 L HH Aphrodite 36* L EH Aphrodite 40* L EH Aquarius 24 L HE Aquatelle 149 X HA Arcona 40 DS* L EH or AH Arcona 400 L HA Arpege M EH Arpege (non‐reverse transom)* L HH Athena 38 L AH Atlanta 26 (Viking)* M HE Atlanta 28 M EH Atlantic 36* X EH Atlantic 38 Power Ketch* L HE Atlantic -

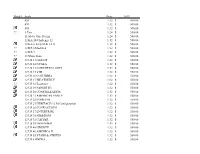

2020 High Point Score Races to Qualify = 9 High Point Totals No

2020 High Point Score Races to Qualify = 9 High Point Totals No. of Total Races High No. of Boats Max Pos Place Boat Skipper Races in Point Score Beat Points Sailed Series 1 Caribbean Magic Schoolden, Greg & Gary 0.866 14 89 103 16 2 Etoile Klik, Marcel 0.825 14 85 104 16 3 Oasis/Sea Hack Copley, David 0.600 14 58 104 16 4 Wavelength Landgrebe , Robert 0.587 15 59 110 16 5 Poco a Poco Marcic, David 0.582 14 57 106 16 6 Kaimana Budar‐Danoff, Jon 0.350 14 27 101 16 7 Japhy's Spirit Vosseller, Richard 0.346 12 25 91 16 8 Pegathy Sheer, Dan 0.316 11 20 82 16 9 Berschert Peers, Peter 0.140 9 3 70 16 10 Swellville Anderson, John 0.000 5 17 37 16 10 Incommunicado Polk, Tim & Tracey, Ed 0.000 2 15 15 16 10 Kooza Snyder, David 0.000 1 0 7 16 Wednesday Night Series CBYRA Races Series 1 Star Spangled Classic 1 Etiole PHRF‐N 2 Caribbean Magic 1 Etoile Macel & Barbie Klik 3 Wavelength Multi‐Hull Series 2 1 Temple of the Wind Douglas Dykman 1 Caribbean Magic 2 Cecile Rose 3 Etolie Francis Scott Key Classic Series 3 PHRF‐N 1 Etoile 1 Incommunicado Polk, Tim & Tracey, Ed 2 Caribbean Magic 2 Kokomo Express Terri High Brett Sorensen 3 Oasis/Sea Hack Multi‐Hull A Series Ending Pursuit 1 OrgaZmaron Joshua Colwell 1 Caribbean Magic 2 Oasis/Sea Hack Multi‐Hull B 3 Wavelength 1 Flipper John Wayshner 4/27/2021 Regatta Management Solutions - Race Registration System - Final Results : 2020 Francis Scott Key Classic Finall Ressulltsts 2020 Francciiss Scco Key Cllassssiicc First Gun Time: 11:00:00 Race Conditions: Started at 6kts diminished to less then 2kts Fleet Name Yacht Name Club Sail Boat Type Rating DIV Div Sail Finish Elapsed Corr. -

Bargain Voyagers Ocean-Worthy, and Affordable

USED BOAT REVIEW CLASSIC CRUISERS FOR LESS THAN $75,000 The Endeavour 37 was based on a Lee Creekmore hull that was cut in half and extended. The handsome Luders 33 was the boat in which teenager Robin Lee Graham completed his historic cir- cumnavigation. Arthur Edmunds designed the full-keel Princess 36 aft-cockpit ketch and the larger Coyle Brian by Photo Mistress 39 center-cockpit ketch. None of these boats are fancily finished, but the fiberglass work is solid and well executed. They’re Bargain Voyagers ocean-worthy, and affordable. The Princess 36 was in production from roughly 1972 to 1982. We’d look for PS picks a few recession-proof a later model year; prices are under cruisers worthy of sweat equity. $50,000. BRISTOL 35.5C et’s say you’re looking to buy a board engine. Too small, however, to Bristol Yachts was founded by Clint L boat for summer cruising along satisfy our new criteria. So we need Pearson, after he left Pearson Yachts the coastal U.S. or on the Great Lakes, to jump up in size. As we culled in 1964. His early boats were Ford one that, when the time is right, is through the possibilities, we found and Chevy quality, good but plainly also capable of taking you safely and a fairly narrow range of boat lengths finished, like the Allieds. Over the efficiently to Baja or the Bahamas, and vintages that satisfy the criteria. years this changed, so that by the and perhaps even island-hopping Of course, there always are excep- late 1970s and early 1980s, his boats from Miami to the West Indies. -

Valid List by Yacht Name Page 1 of 25

October 6, 2005 2005 Valid List by Yacht Name Page 1 of 25 Yacht Name Last Name Yacht Design Sail Nbr Record Date Fleet Racing Cruising CORREIA O DAY MARINER 3181 R032105 MAT U294 U300 SCHMID ADVANCE 36 50172 C062805 MHD 123 129 A FRAYED KNOT APPLE CAL 31 85 R050805 PLY 168 183 ABRACADABRA KNOWLES J 44 WK 42846 R052905 GOM 36 48 ACADIA KEENAN CUSTOM 1001 R041105 GOM 123 123 ACHIEVER V FLANAGAN J 105 442 R022605 MHD 81 90 ACTAEA CONE HINCKLEY B40-3 3815 R061305 NEW 144 156 ADAJIO DOHERTY TARTAN 31 N082105 COD 159 171 ADELINE SCITO 20914 N081105 NBD 216 231 ADRENALIN RUSH HARVEY J 24 4139 R052205 JBE 168 174 ADRENALINE KOOPMAN MELGES 24 514 R052205 JBE 102 108 ADVENTURE CARY SABRE 30-3 168 R032705 GOM 162 174 AEGIR GIERHART, JR. J 105 51439 R051505 MRN 90 96 AEOLUS MITCHELL CAL 33-2 R021305 MHD 144 156 AEQUOREAL RASMUSSEN O DAY 34 51521 R041005 MRN 147 159 AFFINITY DESMOND SWAN 48-2 50922 R051505 MRN 36 39 AFTER YOU MORRIS J 80 261 R062205 GOM 114 123 AFTERGLOW WEG HINCKLEY SW 43TM 43602 R041105 GOM 84 96 AGORA POWERS SHOW 34 50521 R032705 CYC 135 147 AIR EXPRESS GOLDBERG S2 9.1 31753 R052205 JBE 132 144 AIRDOODLE SMITH J 24 2109 R052205 JEB 168 174 AIRTHA SPIECKER ALERION EXPRESS 28-2 227 R021305 PTS U165 U171 AJA ALEXANDER TARTAN 40 41276 C081105 CYC 117 120 AKEEPAH GRAUL CAL 2-29 146 R050105 NHT 189 201 AKELA PIERCE S2 7.9 390 N032705 GOM 174 183 AKUBBA GOODDAY J 44 B96 R061905 NEW 27 39 AL FRESCO PELSUE TARTAN 30 20486 R052205 JBE 183 195 ALACITY TEHAN C&C 29-1 643 R052205 JBE 174 186 ALANNAH SQUIRE COLGATE 26 152 R070605 MHD 162 168 -

Pricesheet with Model Additions-Coallated

Model Scale Price 2019 420 1:12 ($ 500.00) 470 1:12 ($ 500.00) 505 1:12 ($ 500.00) ?? 1 Ton 1:24 ($ 550.00) 11 Meter One Design 1:24 ($ 550.00) 12 KA 10 Challenge 12 1:32 ($ 550.00) 12 KA 6 AUSTRALIA II 1:32 ($ 550.00) ?? 12 KZ 3 Modified 1:32 ($ 550.00) ?? 12 KZ-7 1:32 ($ 550.00) ?? 12 Meter Kate 1:32 ($ 550.00) 12 US 11 GLEAM 1:32 ($ 550.00) 12 US 12 NYALA 1:32 ($ 550.00) 12 US 14 NORTHERN LIGHT 1:32 ($ 550.00) 12 US 15 VIM 1:32 ($ 550.00) 12 US 16 COLUMBIA 1:32 ($ 550.00) 12 US 17 WEATHERLY 1:32 ($ 550.00) ?? 12 US 18 Easterner 1:32 ($ 850.00) 12 US 19 NEFERTITI 1:32 ($ 550.00) 12 US 20 CONSTELLATION 1:32 ($ 550.00) 12 US 21 AMERICAN EAGLE 1:32 ($ 550.00) 12 US 22 INTREPID 1:32 ($ 550.00) 12 US 23 HERITAGE-12 M Configuration 1:32 ($ 550.00) 12 US 26 COURAGEOUS 1:32 ($ 550.00) 12 US 27 ENTERPRISE 1:32 ($ 550.00) 12 US 30 FREEDOM 1:32 ($ 550.00) 12 US 32 CLIPPER 1:32 ($ 550.00) 12 US 33 DEFENDER 1:32 ($ 550.00) 12 US 40 LIBERTY 1:32 ($ 550.00) 12 US 46 AMERICA II 1:32 ($ 550.00) 12 US 55 STARS & STRIPES 1:32 ($ 550.00) 12 US 6 ONIWA 1:32 ($ 550.00) 12 US 61 USA 1:32 ($ 550.00) 1D 35 1:24 ($ 550.00) ?? 420 Jib 1:12 ($ 150.00) ?? 420 Sails 1:12 ($ 300.00) 470 w/ Sails 1:12 ($ 850.00) ?? 49er Skiff 1:24 ($ 550.00) Able Apogee 50 1:32 ($ 550.00) ?? Aerodyne 38 1:24 ($ 550.00) ?? Aerodyne 42 1:24 ($ 550.00) AGS-26 Class USN Survey Ship 1:92 ($ 550.00) Airco Distributor 1:24 ($ 550.00) Alberg 30 1:24 ($ 550.00) Alberg 35 1:24 ($ 550.00) ?? Alberg 36 1:24 ($ 550.00) Alberg 37 1:24 ($ 550.00) ?? Alberg C 22 1:24 ($ 550.00) Albin Nimbus 42 1:24 -

Valid List by Fleet, Last Name Page 1 of 26

Date 10/19/2012 2012 Valid List by Fleet, Last Name Page 1 of 26 Fleet: Boston-MA Last Name First Name Fleet Yacht Name Design Sail Nbr Record Date Racing Cruising Bedingfield Blake BSN2 Sojourner Pearson 365 S R 258 R051012 225 228 Boyd/Wiest Dan/Mitch BSN2 Wildthing J 109 272 R042212 66 78 Brun-Cottan Georges BSN2 Foot Loose J 30 467 R042212 135 141 Caron David BSN2 Legacy Hunter 30 T M N080712 180 186 Childs Kathleen BSN2 Mr. Smooch C&C 34 30444 R081012 150 162 Claffey James BSN2 Flying Cloud Tartan 28 111 R042212 192 207 Davis Andrew BSN2 Destiny J 37 W K 50987 R051012 93 96 Di Pietro Joshua BSN2 Dawn Rain Tartan 27 60381 N042112 237 249 Everett Patrick BSN2 Wango Seidelmann 37 38 R042212 138 153 Feeney Stephen BSN2 Impulse Pearson 36-2 21090 R042212 138 150 Hardy Ernest BSN2 Jaguar J 105 102 R042212 90 96 Hodgman Leslee BSN2 Pajama Girl Sabre 34 62 R051012 174 180 Hyde Jr. Richard W. BSN2 Freightrain Frers 36 40926 R042212 90 102 Klim Marty BSN2 Flingo Bingo Islander 30-2 14332 C071212 186 198 Lanza Jonathan BSN2 Chandele Pearson 10 M 179 N081012 156 168 Lawton Richard BSN2 Spirit C&C 34 30372 R042212 150 162 Mascott J Bard BSN2 Two If By Sea J 105 209 R042212 90 96 Mc Dougall David BSN2 Candy G Macgregor 26 M 60356 N042212 228 234 Melcher Dwayne BSN2 "Sloopy" Lacoste 42 S E 40779 R042212 72 84 Pomer John BSN2 Ophelia Capri 22 W K 281 R050412 219 228 Reardon Greg BSN2 Someday Hunter 376 S D H 376 N042212 132 141 Smith Robert BSN2 Outter Limits Capri 22 W K R042212 219 225 Talbot Jeffrey BSN2 Tachy Tartan Ten 138 R042212 126 132 Winkler