Rural Commercialisation Tspace.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reichertshofener Anzeiger Nr. 21 Vom 28. Mai 2021

Amts- und Mitteilungsblatt der Verwaltungsgemeinschaft Reichertshofen Markt Reichertshofen - Gemeinde Pörnbach Verantwortlich für amtliche Bekanntmachungen: Verwaltungsgemeinschaftsvorsitzender Bürgermeister Michael Franken / Stellvertreter Bürgermeister Helmut Bergwinkel Reichertshofen: Rathaus Tel: 0 84 53 / 5 12 - 0 • Rathaus Fax: 0 84 53 / 5 12 - 60 • Bauhof Tel. 0 84 53 / 33 16 59 • Homepage: http://www.reichertshofen.de •Email:info § reichertshofen.de Pörnbach: Rathaus Tel. 0 84 46 / 10 33 • Rathaus Fax: 0 84 46 / 16 91 • Email: poernbach § reichertshofen.de Öffnungszeiten der Rathäuser Reichertshofen und Pörnbach: Bis auf weiteres nur nach vorheriger Terminvereinbarung. Herausgeber: F. Prummer, Druck, Verlag u. Anzeigen: PRIMO-Ortsnachrichten Verlag GmbH, 81825 München, Hans-Pfann-Str. 1c, ˛ 0 89 / 42 24 26, Fax: 0 89 / 42 21 23 Mit der Einsendung oder Überlassung von Textbeiträgen und Fotos übernimmt der Verfasser bzw. Einsender die Gewähr dafür, dass durch eine Veröffentlichung keine Urheberrechte verletzt werden und überträgt damit gleichzeitig das Recht zur Veröffentlichung an die Gemeinde und an den Verlag. 61.62. JAHRGANG JAHRGANG FREITAG,FREITAG, 18. DEZEMBER 28. MAI 2021 2020 NUMMERNUMMER 51/52 21 In lebensbedrohlichen Situationen wählen Sie weiterhin die Nr 112. Aktuelle Informationen finden Sie auch auf unseren Homepages Den ärztlichen Notdienst für PÖRNBACH können Sie ebenfalls www.reichertshofen.de und www.poernbach.de! unter Tel. 116 117 erfragen. Bei gleicher Umgebung lebt doch jeder in einer anderen Notfallbetreuung Welt. Arthur Schopenhauer (1788 – 1860) • Der Hauswirtschaftliche Fachservice (HWF) unterstützt bei fami- liären Notfällen, wie z.B. bei Erkrankung der Mama, Zuhause-bei Krankenhausaufenthalt-Risiko-Schwangerschaft oder Kur/Reha. INHALT: Die Fachkräfte übernehmen die Kinderbetreuung und Haushalts- führung. Darüber hinaus unterstützen sie Senioren und Alleinste- Bek. -

Teisnach Aktuell Ausgabe Juli 2019

an alle Haushalte | Ausgabe 02 | Juli 2019 HEIMAT MIT PERSPEKTIVE TEISNACH AKTUELL IMPRESSUM & REDAKTION: GESTALTUNG & SATZ MARKT TEISNACH, PRÄLAT-MAYER-PLATZ 5 SOWIESO CREATIV.HANDWERK E.K. 94244 TEISNACH, 09923 / 8011-0 MATZELSDORF 31, 93444 BAD KÖTZTING MAIL: [email protected] 09945 / 94337-0, [email protected] TEISNACHER CHRONIK VERANSTALTUNGEN CHRISTOPHORUS MEDAILLE HEIMAT MIT PERSPEKTIVE WEB: WWW.TEISNACH.DE WEB: WWW.CREATIV-HANDWERK.DE Ereignisse im Markt | S.5 Feste, Konzerte & mehr | S.25 Ehrung für Lebensretter | S. 39 GRUSSWORT ihres 1. Bürgermeisters Daniel Graßl Liebe Mitbürgerinnen, Rahmenprogramm eingeladen. An diesem Tag müssen Sie, liebe Teisnacherinnen liebe Mitbürger, und Teisnacher, einige Einschränkungen in Kauf nehmen. Um einen reibungslosen mit dieser Broschüre möchten wir Ihnen Ablauf der Veranstaltung sicherzustellen, als Gemeindebürger aktuelle Informa- muss die REG 18 (Kaikenrieder Straße) tionen und Berichte aus Ihrer Heimatge- zwischen der Apotheke und der meinde zweimal pro Jahr kostenlos nach Abzweigung Richtung Wetzelsdorf als Hause liefern. Einbahnstraße in Fahrrichtung Teisnach Oed geführt werden. Es werden aber Wenn man sich Gedanken macht, was alle betroffenen Ausfahrten beschil- innerhalb des letzten Halbjahres 2019 dert. Für alle Besucher ist die Firma geschehen ist, fällt einem vieles ein. Es Rohde & Schwarz dennoch an diesem gibt mit Sicherheit sehr viele Ereignisse Tag bequem zu erreichen. Es fahren an die man zurückdenkt. In unserer durchgehend Pendelbusse von Broschüre „Teisnach aktuell“ können ausgewiesenen Bushaltestel- wir natürlich nicht alles abdecken, aber len (Busbahnhof, Wetzelsdorf, wir haben wieder versucht einen breiten Kartbahn und EDEKA-Markt) in Querschnitt für Sie zusammenzufassen. Richtung Rohde & Schwarz, welche Sie An dieser Stelle sei auch erwähnt, dass die kostenlos nutzen können. -

200703 Auswertung Gesamt

STADTRADELN 2020 Gesamtauswertung Aktionszeitraum: Landkreis Pfaffenhofen a.d.Ilm 4. bis 24.07.2020 Insgesamt geradelte Kilometer: 260.053 km CO2-Vermeidung: 37 t Teams: 88 Aktive Radelnde: 981 Politiker: 49 theoretische Radlkilometer je EW: 2,03 km Kommunenteilnahme: Name Anzahl Teams aktive RadlerInnen zurückgelegte km vermiedenes CO2 in t 1 Gerolsbach 14 150 30.747 km 5 3.609 2 Pfaffenhofen 28 312 86.277 km 11 26.035 3 Pörnbach 3 21 3.893 km 1 2.165 4 Reichertshofen 5 42 14.424 km 2 8.208 5 Scheyern 6 48 11.377 km 2 4.929 6 Vohburg 13 100 31.964 km 5 8.367 7 Wolnzach 6 47 15.198 km 2 11.657 Teilnahme als Kommunenteam 8 Geisenfeld 1 56 15.734 km 2 11.432 9 Hohenwart 1 2 526 km <1 4.777 10 Ilmmünster 1 25 8.283 km 1 2.270 11 andere - Landkreis 10 178 41.630 km 6 Gesamt 88 981 260.053 km 37 127.815 Team-Ergebnisse absolut: Welches Team legt die meisten km mit dem Rad zurück? 1 Geisenfeld Kreis Pfaffenhofen a.d.Ilm15.734 km 2.313 kg CO2 2 MBB SG Manching Kreis Pfaffenhofen a.d.Ilm13.019 km 1.914 kg CO2 3 Wasserwacht Manching Kreis Pfaffenhofen a.d.Ilm9.926 km 1.459 kg CO2 4 geschwisterstolz Pfaffenhofen 9.497 km 1.396 kg CO2 Mittwochsradler der NaturFreundePfaffenhofen 9.257 km 1.361 kg CO2 5 Offenes Team - Vohburg a.d.DonauVohburg 9.205 km 1.353 kg CO2 6 Fridays For Future Pfaffenhofen Pfaffenhofen 9.011 km 1.325 kg CO2 7 Ilmmünster Kreis Pfaffenhofen a.d.Ilm8.283 km 1.218 kg CO2 8 Landratsamt Pfaffenhofen Kreis Pfaffenhofen a.d.Ilm7.039 km 1.035 kg CO2 9 TV-Radler Vohburg 6.481 km 953 kg CO2 10 RSV Hallertau Pfaffenhofen 6.035 km 887 kg CO2 11 Team One Gerolsbach Gerolsbach 5.902 km 868 kg CO2 12 Offenes Team - Reichertshofen Reichertshofen 5.885 km 865 kg CO2 STADTRADELN 2020 Gesamtauswertung Aktionszeitraum: Landkreis Pfaffenhofen a.d.Ilm 4. -

XI. Summarische Uebersicht Der Kodizes in Den Bayerischen Landesarchiven

XI. Summarische Uebersicht der Kodizes in den bayerischen Landesarchiven. Vorbemerkung. Ueber das sechszehnte Jahrhundert ist diese Zusammenstellung nicht hinausgeführt, und auch für dieses begnügte man sich mit einer Auswahl, weniger historisch wichtige Ämtsbücher wurden ausgeschlossen. Für die früheren Jahrhunderte geben die Zahlen den Oesammtbestand an, und war für die Ein- reihung je nach der Entstehungszeit maaesgebend die Niederschrift der ältesten Theile eines Kodex und bei Sammelbänden das Alter der frühesten Bestandtheile. Nachträge, die in vielen sich finden, konnten hier nicht berücksichtigt werden. Die Zahl der durch Alter, Inhalt, Illustrationen oder auch durch eine seltene kunstreiche Art des Einbandes hervorragenden Kodizes ist durch fetteren Druck ausgezeichnet | 1 r e Archivaliengruppe Jahrhundert Fortlfd Numme IX. X. XI. XII. ΧΙΠ.Ι XIV. XV. XVI I. BtlcìtirtliT il MDukei. A. Hook- lud Domstifte. fl 1 Augsburg 2 11 7 66 145 2 Bamberg . 1 5 3 Berchtesgaden .... β fl 2 99 4 Brixen fl 3 # # 5 Chiemsee . 1 1 fl 6 Eichstädt 11 62 73 7 Ellwangen β . 1 1 * 8 Preising 1 • • » 1 8 60 76 fl 8 9 Kempten fl. 4 • • • 41 121 Archivaliache Zeitschrift. IX. 18 Brought to you by | New York University Bobst Library Technical Services Authenticated Download Date | 9/21/15 7:51 PM 194 Summarische Ucbersiclit fier Kodizes in den bay er. Landesnrchiven. a S J a h r li u η (1 c r t ? a Archiv aliengruppe „tO s0 fe» IX. X. XI XII XIII. XIV. XV. XVI. 10 Mainz • t 2 1 4 11 Münster . 1 . 10 11 12 Passau 1 1 * 4 42 » 205 13 Begensburg • 1 5 14 49 14 Salzburg • I · . -

Gemeindeanzeiger 2020

2 Vorwort des Bürgermeisters Dezember 2020 Liebe Mitbürgerinnen und Mitbürger, liebe Klousterer, Sie sind es gewohnt, dass dem jährlich Durch das Auftauchen des Virus SARS II– Aber sie schließt nicht aus, dass wir sterben erscheinenden Gemeindeanzeiger ein Covid 19 ist die Aufgabenbewältigung nicht müssen.“ Es macht mir Sorge, dass diese Geleitwort des Bürgermeisters voransteht. einfacher geworden. Der Staat, an dessen Wahrheit vielfach ausgeblendet wird. Wieviel Da der „Dane“, dem eine große Mehrheit der Tropf eine finanzschwache Gemeinde, wie ist uns die Natur des Menschen als Wählerinnen und Wähler im März dieses wir es sind, hängt, wird nicht beliebig lange Gemeinschaftswesen noch wert? Ist es Jahres dieses Amt übertragen hat, leider seit beliebig viel Geld ausgeben können, wenn bedeutungslos, wenn Beziehungen, ob in der längerer Zeit wegen Krankheit an der gleichzeitig auf der anderen Seite immer Familie, in Vereinen oder in den Gemeinden Ausübung seines Amtes verhindert ist, fällt weniger Steuergeld eingenommen werden (egal ob politische oder kirchliche Gemeinde) mir die Aufgabe zu, diese Tradition kann. Die jetzigen Kreditaufnahmen werden wegbrechen? Was ich sagen will: Natürlich ist fortzusetzen. Ich will das gerne tun, nachdem unsere Enkel und Urenkel zurückzahlen die Gesundheit ein wichtiges Gut und dafür mir der neugewählte Gemeinderat in seiner müssen; das sind genau die, denen heute ein muss gekämpft werden. Es muss aber ganz ersten Sitzung die Stellvertretung des Teil der Jugend, wie wir sie erleben durften, sicher auch die Frage gestellt werden, ob Bürgermeisters übertragen hat. Sie kennen genommen wird. Aber nicht nur finanziell einige Mittel in diesem Kampf nicht teilweise mich! Sie wissen, dass ich keine einfach werden sich aus dieser Pandemie Folgen mehr Schaden als Nutzen bringen. -

Provenienzen Von Inkunabeln Der BSB

Provenienzen von Inkunabeln der BSB Nähere historisch-biographische Informationen zu den einzelnen Vorbesitzern sind enthalten in: Bayerische Staatsbibliothek: Inkunabelkatalog (BSB-Ink). Bd. 7: Register der Beiträger, Provenienzen, Buchbinder. [Redaktion: Bettina Wagner u.a.]. Wiesbaden: Reichert, 2009. ISBN 978-3-89500-350-9 In der Online-Version von BSB-Ink (http://inkunabeln.digitale-sammlungen.de/sucheEin.html) können die in der Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek vorhandenen Inkunabeln aus dem Besitz der jeweiligen Institution oder Person durch Eingabe des Namens im Suchfeld "Provenienz" aufgefunden werden. Mehrteilige Namen sind dabei in Anführungszeichen zu setzen; die einzelnen Bestandteile müssen durch Komma getrennt werden (z.B. "Abensberg, Karmelitenkloster" oder "Abenperger, Hans"). 1. Institutionen Ort Institution Patrozinium Abensberg Karmelitenkloster St. Maria (U. L. Frau) Aichach Stadtpfarrkirche Beatae Mariae Virginis Aldersbach Zisterzienserabtei St. Maria, vor 1147 St. Petrus Altdorf Pfarrkirche Altenhohenau Dominikanerinnenkloster Altomünster Birgittenkloster St. Peter und Paul Altötting Franziskanerkloster Altötting Kollegiatstift St. Maria, St. Philipp, St. Jakob Altzelle Zisterzienserabtei Amberg Franziskanerkloster St. Bernhard Amberg Jesuitenkolleg Amberg Paulanerkloster St. Joseph Amberg Provinzialbibliothek Amberg Stadtpfarrkirche St. Martin Andechs Benediktinerabtei St. Nikolaus, St. Elisabeth Angoulême Dominikanerkloster Ansbach Bibliothek des Gymnasium Carolinum Ansbach Hochfürstliches Archiv Aquila Benediktinerabtei -

Amtsblatt 01/2019

1 Amtsblatt FÜR DEN LANDKREIS REGEN Verantwortlicher Herausgeber: Landratsamt REGEN Erscheint nach Bedarf - Zu beziehen beim Landratsamt Regen Einzelbezugspreis: 0,50 € ___________________________________________________________________________ Nr. 1 Regen, 25.01.2019 Inhalt: Einwohnerzahlen – Stand 30.06.2018 Vollzug der Bayer. Bauordnung; Baugenehmigung für das Bauvorhaben: Neubau eines Pferdestalles mit Nebenge- bäude und Auslauf in Kirchdorf i. Wald, Abtschlag, Kirchdorfer Str. 11; Bauherr: Sabrina Ebner; Hintberg 30a, 94259 Kirchberg i. Wald Verordnung zur Änderung der Verordnung über das Landschaftsschutzgebiet „Bayerischer Wald“ vom 23.01.2019 2 10-0132 Für den Landkreis Regen und die Gemeinden des Landkreises Regen ergeben sich folgende auf Basis Zensus 2011 fortgeschriebene Einwohnerzahlen zum Stand 30. Juni 2018: Landkreis Regen Niederbayern Gemeinde Einwohner insgesamt Achslach 910 Arnbruck 1 932 Bayerisch Eisenstein 1 035 Bischofsmais 3 150 Bodenmais, M 3 492 Böbrach 1 640 Drachselsried 2 462 Frauenau 2 727 Geiersthal 2 201 Gotteszell 1 219 Kirchberg i.Wald 4 347 Kirchdorf i.Wald 2 109 Kollnburg 2 795 Langdorf 1 830 Lindberg 2 275 Patersdorf 1 707 Prackenbach 2 752 Regen, St 11 005 Rinchnach 3 069 Ruhmannsfelden, M 2 060 Teisnach, M 2 939 Viechtach, St 8 331 Zachenberg 2 078 Zwiesel, St 9 450 zusammen 77 515 folgendem Link abgerufen werden: https://www.statistikdaten.bayern.de/genesis/online?sequenz=tabelleAufbau&selectionname=12411-009r (kopieren Sie diesen Link bitte in die Browserzeile, falls der direkte Aufruf nicht funktioniert). Regen, den 07.01.2019 Landratsamt gez. Röhrl Landrätin 3 Vollzug der Bayer. Bauordnung; Öffentliche Bekanntmachung der Baugenehmigung gemäß Art. 66 Abs. 2 BayBO Bausachen-Nummer 00580-I18 Bauherr Sabrina Ebner, Hintberg 30a, 94259 Kirchberg i. -

3D-Segmentierung Von Einzelbäumen Und Baumartenklassifikation Aus

TECHNISCHE UNIVERSITAT¨ MUNCHEN¨ Institut fur¨ Photogrammetrie und Kartographie Fachgebiet Photogrammetrie und Fernerkundung 3D-Segmentierung von Einzelb¨aumen und Baumartenklassifikation aus Daten flugzeuggetragener Full Waveform Laserscanner Josef Reitberger Dissertation 2010 TECHNISCHE UNIVERSITAT¨ MUNCHEN¨ Institut fur¨ Photogrammetrie und Kartographie Fachgebiet Photogrammetrie und Fernerkundung 3D-Segmentierung von Einzelb¨aumen und Baumartenklassifikation aus Daten flugzeuggetragener Full Waveform Laserscanner Josef Reitberger Vollst¨andiger Abdruck der von der Fakult¨at fur¨ Bauingenieur- und Vermessungswesen der Technischen Universit¨at Munchen¨ zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Doktor-Ingenieurs (Dr.-Ing.) genehmigten Dissertation. Vorsitzende: Univ.-Prof. Dr.-Ing. L. Meng Prufer¨ der Dissertation: 1. Univ.-Prof. Dr.-Ing. U. Stilla 2. Univ.-Prof. Dr. techn. W. Wagner, Technische Universit¨at Wien/Osterreich¨ 3. Prof. Dr.-Ing. P. Krzystek, Hochschule Munchen¨ Die Dissertation wurde am 02.03.2010 bei der Technischen Universit¨at Munchen¨ eingereicht und durch die Fakult¨at fur¨ Bauingenieur- und Vermessungswesen am 26.04.2010 angenommen. Kurzfassung Das luftgestutzte¨ Laserscanning hat sich in den letzten 15 Jahren rasant entwickelt und hebt sich insbesondere im Waldbereich von anderen Fernerkundungsmethoden ab, weil die Wald- struktur an Lucken¨ von den Laserstrahlen durchdrungen wird. Bedingt durch die Einschr¨ankung der meisten konventionellen Lasersysteme, nur die ersten und letzten Reflexionen zu erfas- sen, konzentrierten sich die Forschungsaktivit¨aten der letzten Jahre auf die Ableitung pr¨aziser Oberfl¨achen- und Gel¨andemodelle, sowie auf die Nutzung dieser Modelle fur¨ die automatische Ermittlung von Waldinformationen. Im Gegensatz dazu besitzen die neuartigen Full Waveform Lasersysteme die F¨ahigkeit, den reflektierten Laserimpuls vollst¨andig aufzuzeichnen. Dadurch wird neben der Oberfl¨ache und dem Boden des Waldes auch die dazwischenliegende Wald- struktur detailliert erfasst. -

Vdk Kreiskegelturnier 2019 Kreisverband „Arberland“

VdK Ortsverband Regen Ergebnisliste VdK Kreiskegelturnier 2019 Kreisverband „Arberland“ in der Kegelhalle Regen- Oleumhütte am 04./05. Oktober Siegerliste VdK-Kegelturnier 2019 Mannschaft Herren gesam. Platz Name OV In die vollen Abräumen Mannschaft Ergebnis Wengler Dieter Regen 62 34 96 184 1 Fenzl Karl Regen 61 27 88 184 Straßer Eberhard Regen 55 23 78 165 2 Nirschl Josef Regen 54 33 87 165 Graf Hans Regen 61 26 87 160 3 Kroner Hans Regen 56 17 73 160 Bernreiter Karl Zwiesel 71 22 93 150 4 Hannes Max Zwiesel 42 15 57 150 Rankl Alfred Kirchdorf 65 17 82 148 5 Guba Peter Kirchdorf 48 18 66 148 Ebner Franz Regen 50 26 76 148 6 Brandl Max Regen 56 16 72 148 Mühlbauer Paul Zellertal 45 24 69 145 7 Schaffer Hans Zellertal 51 25 76 145 Oppowa Richard Rinchnach 59 35 94 145 8 Gigl Karl Rinchnach 34 17 51 145 Peschl Heinrich Frauenau 45 27 72 136 9 Hirschauer Ulli Frauenau 46 18 64 136 Fischer Max Zwiesel 59 18 77 134 10 Weber Franz Zwiesel 50 7 57 134 Müldner Rudi Kirchdorf 50 13 63 134 11 Wildfeuer Herbert Kirchdorf 46 25 71 134 Förster Günther Kirchdorf 53 24 77 126 12 Ebner Karl-Heinz Kirchdorf 41 8 49 126 Schlecht August Kollnburg 41 24 65 122 13 Hanninger Alois Kollnburg 41 16 57 122 Reith Johann Zellertal 58 9 67 119 14 Schötz Willi Zellertal 43 9 52 119 Wilhelm Karl Kollnburg 41 9 50 107 15 Klomann Herbert Kollnburg 40 17 57 107 Siegerliste VdK-Kegelturnier 2019 Mannschaft Herren gesam. -

T-Pvs/De(2015)

Strasbourg, 5 March 2015 T-PVS/DE (2015) 8 [de08e_15.doc] CONVENTION ON THE CONSERVATION OF EUROPEAN WILDLIFE AND NATURAL HABITATS GROUP OF SPECIALISTS ON THE EUROPEAN DIPLOMA FOR PROTECTED AREAS 13 March 2015 Strasbourg, Palais de l’Europe, Room 11 ---ooOoo--- REPORT ON AN EXCEPTIONAL ON-THE-SPOT APPRAISAL VISIT TO THE BAYERISCHER WALD NATIONAL PARK (GERMANY) 24 – 25 FEBRUARY 2015 Document prepared by Olivier Biber (Switzerland) This document will not be distributed at the meeting. Please bring this copy. Ce document ne sera plus distribué en réunion. Prière de vous munir de cet exemplaire. T-PVS/DE (2015) 8 - 2 - 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1. Reason for the on-the-spot appraisal In January 2015, the Secretariat of the Biodiversity Unit of the Directorate of democratic governance (Directorate General II) of the Council of Europe was alerted on the possible severe threats which may affect the outstanding biodiversity of the Bayerischer Wald National Park, holder of the European Diploma since 1986, as a result of the planned imminent construction of a large wind farm in the immediate vicinity of the Park. Taking into account the urgency of the situation, an exceptional on-the-spot appraisal visit was decided, applying Article 8 of the Revised Regulations for the European Diploma for Protected Areas, and received the agreement of the national authorities in Germany. 1.2. Bayerischer Wald National Park (NP) Bayerischer Wald National Park has been awarded the European Diploma for Protected Areas in 1986. 2. THE WIND FARM PROJECT WAGENSONNRIEGEL 2.1. Background and history of the wind farm project The wind farm project under consideration – Wagensonnriegel, an area of 1700 ha on a forested hill range culminating at 950 masl -- has originated in the German Concept for the promotion of renewable energies in the frame of the decided phasing out of the use of nuclear energy (Energiewende, Energiekonzept Ausstieg aus der Atomenergie). -

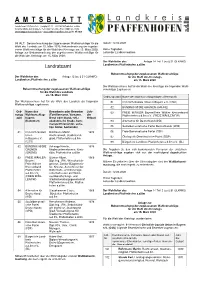

Amtsblatt 05

AMTSBLATT Landratsamt Pfaffenhofen – Hauptplatz 22 – 85276 Pfaffenhofen a.d.Ilm Verantwortlich: Astrid Appel – Tel. 08441/27-394 – Fax: 08441/27-13394 [email protected] - www.landkreis-pfaffenhofen.de Nr. 05/2020 INHALT: Bekanntmachung der zugelassenen Wahlvorschläge für die Datum: 12.02.2020 Wahl des Landrats am 15. März 2020; Bekanntmachung der zugelas- senen Wahlvorschläge für die Wahl des Kreistags am 15. März 2020; Heinz Taglieber, Anlage zur Bekanntmachung der zugelassenen Wahlvorschläge für Leiter der Landkreiswahlen die Wahl des Kreistags am 15. März 2020; _______________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________ Der Wahlleiter des Anlage 14 Teil 1 (zu § 51 GLKrWO) Landkreises Pfaffenhofen a.d.Ilm Landratsamt Bekanntmachung der zugelassenen Wahlvorschläge Der Wahlleiter des Anlage 15 (zu § 51 GLKrWO) für die Wahl des Kreistags Landkreises Pfaffenhofen a.d.Ilm am 15. März 2020 Der Wahlausschuss hat für die Wahl des Kreistags die folgenden Wahl- Bekanntmachung der zugelassenen Wahlvorschläge vorschläge zugelassen: für die Wahl des Landrats am 15. März 2020 Ordnungszahl Name des Wahlvorschlagsträgers (Kennwort) Der Wahlausschuss hat für die Wahl des Landrats die folgenden 01 Christlich-Soziale Union in Bayern e.V. (CSU) Wahlvorschläge zugelassen: 02 BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN (GRÜNE) Ord- Name des Bewerberin oder Bewerber Jahr 03 FREIE WÄHLER Bayern/Freie Wähler Kreisverband nungs Wahlvorschlag- (Familienname, Vorname, der Pfaffenhofen a.d.Ilm e.V. (FREIE WÄHLER/FW) zahl trägers Beruf oder Stand, evtl.: Geburt (Kennwort) akademische Grade, kom- 04 Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) munale Ehrenämter, sons- tige Ämter, Gemeinde) 05 Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands (SPD) 01 Christlich-Soziale Rohrmann Martin, 1972 06 Freie Demokratische Partei (FDP) Union Rechtsanwalt, Stadtratsmit- 07 Ökologisch-Demokratische Partei (ÖDP) in Bayern e.V. -

P R E S S E M I T T E I L U

Hometown Dynamics Fraueninsel on Lake Chiemsee: Artists’ paradise and place of longing The peaks of the Chiemgau Alps rise majestically to the south-east of the small island of Fraueninsel on Lake Chiemsee. The leaves of the ancient trees sway gently in the wind on the shores of Bavaria’s largest lake – accompanied by the constant splashing of the waves. The shallow banks, small bays and extensive moorland combine to create a picturesque lake landscape like no other. Frauenchiemsee artists’ colony: The mythology of a complete natural idyll For centuries, people have been captivated by the beautiful scenery of Lake Chiemsee. In 1828, four young artists from Munich settled on the secluded little island of Fraueninsel on the lake. This marked the birth of the Frauenchiemsee artists’ colony, which includes sculptors and writers and is one of the oldest and best-known artists’ colonies in Europe. The artists record their longing for perfect beauty on canvas using opulent motifs: the romantic fishermen’s houses of the island, the floral gardens, the decorated houses, the breathtaking natural idylls in the interplay of light and cloud shadows. In this way they use their landscape paintings to spread the mythology of Bavaria around the world. Island pottery: Traditional craftsmanship with a love of detail To this day, artists still live on the secluded, car-free Fraueninsel in the middle of Lake Chiemsee. One of them is Georg Klampfleuthner from the island’s pottery. Founded in the year 1609 to serve the monastery, the pottery has been in his family since 1723, and has been passed down from generation to generation.