Enrique Granados and Modern Piano Technique Carol A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Selected Intermediate-Level Solo Piano Music Of

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2005 Selected intermediate-level solo piano music of Enrique Granados: a pedagogical analysis Harumi Kurihara Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Kurihara, Harumi, "Selected intermediate-level solo piano music of Enrique Granados: a pedagogical analysis" (2005). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3242. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3242 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. SELECTED INTERMEDIATE-LEVEL SOLO PIANO MUSIC OF ENRIQUE GRANADOS: A PEDAGOGICAL ANALYSIS A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Harumi Kurihara B.M., Loyola University, New Orleans, 1993 M.M.,University of New Orleans, 1997 August, 2005 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my sincere appreciation to my major professor, Professor Victoria Johnson for her expert advice, patience, and commitment to my monograph. Without her help, I would not have been able to complete this monograph. I am also grateful to my committee members, Professors Jennifer Hayghe, Michael Gurt, and Jeffrey Perry for their interest and professional guidance in making this monograph possible. I must also recognize the continued encouragement and support of Professor Constance Carroll who provided me with exceptional piano instruction throughout my doctoral studies. -

A Comparison of the Piano and Guitar Versions of Isaac Albéniz's Spanish Suite Op

A COMPARISON OF THE PIANO AND GUITAR VERSIONS OF ISAAC ALBÉNIZ'S SPANISH SUITE OP. 47 by YI-YIN CHIEN A LECTURE-DOCUMENT Presented to the School of Music and Dance of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts November 2016 2 “A Comparison of the Piano and Guitar Versions of Isaac Albéniz’s Spanish Suite, Op. 47’’ a document prepared by Yi-Yin Chien in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Musical Arts degree in the School of Music and Dance. This document has been approved and accepted by: Jack Boss, Chair of the Examining Committee Date: November 20th, 2016 Committee in Charge: Dr. Jack Boss, Chair Dr. Juan Eduardo Wolf Dr. Dean Kramer Accepted by: Director of Graduate Studies, School of Music and Dance © 2016 Yi-Yin Chien 3 CURRICULUM VITAE NAME OF AUTHOR: Yi-Yin Chien PLACE OF BIRTH: Taiwan DATE OF BIRTH: November 02, 1986 GRADUATE AND UNDERGRADUATE SCHOOLS ATTENDED: University of Oregon, School of Music and Dance Peabody Institute of the Johns Hopkins University Tainan National University of Arts DEGREES AWARDED: Doctor of Musical Arts, 2016, University of Oregon Master of Music, 2011, Peabody Institute of the Johns Hopkins University Bachelor of Music, 2009, Tainan National University of Arts AREAS OF SPECIAL INTEREST: Piano Pedagogy Music Theory PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE: College Piano Teaching, University of Oregon, School of Music and Dance, 09/2014 - 06/2015 Taught piano lessons for music major and non-major college students Graduate Teaching -

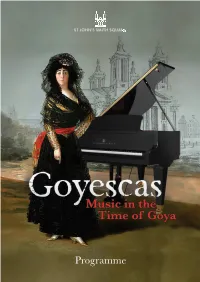

Music in the Time of Goya

Music in the Time of Goya Programme ‘Goyescas’: Music in the Time of Goya Some of the greatest names in classical music support the Iberian and Latin American Music Society with their membership 2 November 2016, 7.00pm José Menor piano Daniel Barenboim The Latin Classical Chamber Orchestra featuring: Argentine pianist, conductor Helen Glaisher-Hernández piano | Elena Jáuregui violin | Evva Mizerska cello Nicole Crespo O’Donoghue violin | Cressida Wislocki viola and ILAMS member with special guest soloists: Nina Corti choreography & castanets Laura Snowden guitar | Christin Wismann soprano Opening address by Jordi Granados This evening the Iberian and Latin American Music Society (ILAMS) pays tribute to one of Spain’s most iconic composers, Enrique Granados (1867–1916) on the centenary year of his death, with a concert programme inspired by Granados’ greatest muse, the great Spanish painter Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (1746–1828), staged amidst the Baroque splendour of St John’s Smith Square – a venue which, appropriately, was completed not long before Goya’s birth, in 1728. Enrique Granados To pay homage to Granados here in London also seems especially fi tting given that the great Composer spent his fi nal days on British shores. Granados Will you drowned tragically in the English Channel along with his wife Amparo after their boat, the SS Sussex, was torpedoed by the Germans. At the height of his join them? compositional powers, Granados had been en route to Spain from New York where his opera, Goyescas, had just received its world premiere, and where he had also given a recital for President Woodrow Wilson; in his lifetime Granados was known as much for his virtuoso piano playing as for his talent as a composer. -

Granados: Goyescas

Goyescas Enrique Granados 1. Los Requiebros [9.23] 2. Coloquio en La Reja [10.53] 3. El Fandango de Candil [6.41] 4. Quejas, ó la Maja y el Ruiseñor [6.22] 5. El Amor y la Muerte: Balada [12.43] 6. Epilogo: Serenata del Espectro [7.39] Total Timings [54.00] Ana-Maria Vera piano www.signumrecords.com The Goyescas suite has accompanied me throughout with her during the recording sessions and felt G my life, and I always knew that one day I would generous and grounded like never before. The music attempt to master it.The rich textures and came more easily as my perspectives broadened aspiring harmonies, the unfurling passion and I cared less about perfection. Ironically this is tempered by restraint and unforgiving rhythmic when you stand the best chance of approaching precision, the melancholy offset by ominous, dark your ideals and embracing your audience. humour, the elegance and high drama, the resignation and the hopefulness all speak to my sense of © Ana-Maria Vera, 2008 being a vehicle, offeeling the temperature changes, the ambiguity, and the emotion the way an actor might live the role of a lifetime. And so this particular project has meant more to me than almost any in my career. Catapulted into the limelight as a small child, I performed around the globe for years before realising I had never had a chance to choose a profession for myself. Early success, rather than going to my head, affected my self-confidence as a young adult and I began shying away from interested parties, feeling the attention wasn't deserved and therefore that it must be of the wrong kind. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 110, 1990-1991, Subscription

&Bmm HHH 110th Season 19 9 0-91 Boston Symphony Orchestra Seiji Ozawa, Music Director 90th Anniversary of Symphony Hall m<K Only The few will own an aldemars. Only the few will seek the exclusivity that comes with owning an Audemars Piguet. Only the few will recognize wn more than a century of technical in- f\Y novation; today, that innovation is reflected in our ultra-thin mech- Memars Piguet anical movements, the sophistica- tion of our perpetual calendars, and more recently, our dramatic new watch with dual time zones. Only the few will appreciate The CEO Collection which includes a unique selection of the finest Swiss watches man can create. Audemars Piguet makes only a limited number of watches each year. But then, that's something only the few will understand. SHREVECRUMP &LOW JEWELERS SINCE 1800 330BOYLSTON ST., BOSTON, MASS. 02116 (617) 267-9100 • 1-800-225-7088 THE MALL AT CHESTNUT HILL • SOUTH SHORE PLAZA Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Grant Llewellyn and Robert Spano, Assistant Conductors One Hundred and Tenth Season, 1990-91 Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. Nelson J. Darling, Jr., Chairman Emeritus J. P. Barger, Chairman George H. Kidder, President Mrs. Lewis S. Dabney, Vice-Chairman Archie C. Epps, Vice-Chairman Mrs. John H. Fitzpatrick, Vice-Chairman William J. Poorvu, Vice-Chairman and Treasurer David B. Arnold, Jr. Avram J. Goldberg Mrs. August R. Meyer Peter A. Brooke Mrs. R. Douglas Hall III Mrs. Robert B. Newman James F. Cleary Francis W. Hatch Peter C. Read John F. Cogan, Jr. Julian T. Houston Richard A. -

Luis Fernando Pérez Piano

LUIS FERNANDO PÉREZ Praised for his virtuosity, his colorful playing and his extraordinary and rare capability to comunicate straight forward to his public, Luis Fernando Pérez is considered to be one of the most excepcional artists of his generation and “The Renaissance of Spanish Piano” (Le Monde). Applauded unanimously by the world critics and owner of numerous prizes as the Franz Liszt (Italy) and the Granados Prize-Alicia de Larrocha prize (Barcelona), Luis Fernando is owner too of the Albeniz Medall, given to him for his outstanding interpretation of Iberia, considered by Gramophone Magazine as “one of the four mythical” (together with those of Esteban Sanchez, Alicia de Larrocha and Rafael Orozco). Luis Fernando belongs to this rare group of outstanding musicians who have been taught by legendary artists; with Dimitri Bashkirov and Galina Egyazarova, students of the great Alexander Goldenweiser - following a straight tradition after Liszt´s considered best student Siloti- further on with Pierre-Laurent Aimard and with the great spanish pianist Alicia de Larrocha and her assistant Carlota Garriga in the Marshall Academy in Barcelona. It is precisely in the Marshall Academy beside Larrocha where he specializes in the interpretation of Spanish Music, obtaining his Masters in Spanish Music Interpretation and where he also works all piano of Federico Mompou with his widow, Carmen Bravo. He has received also continuated lessons and masterclasses from great artists as Leon Fleisher, Andras Schiff, Bruno-Leonardo Gelber, Menahen Pressler, Fou Tsong and Gyorgy Sandor. He has collaborated with numerous orchestras as the Spanish National Orchestra, Montecarlo Filharmonic, Sinfonia Varsovia, Franz Liszt Chamber Orchestra, Filharmonia Baltycka, Enemble Kanazawa (Japan), Real Filarmonía de Galicia, OBC (Barcelona), BOS (Bilbao), Ensemble National de Paris, Brasil National Orchestra…and together with great conductors as Ros Marbá, Georges Tchitchinadze, Kazuki Yamada, Jesús López Cobos, Jean-Jacques Kantorow, Dimitri Liss, Paul Daniel, Rumon Gamba, Carlo Rizzi. -

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: NATIONAL

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: NATIONAL CHARACTER AS EXPRESSED IN PIANO LITERATURE Yong Sook Park, Doctor of Musical Arts, 2005 Dissertation directed by: Bradford Gowen, Professor of Music In the middle of the 19th century, many composers living outside of mainstream musical countries such as Germany and France attempted to establish their own musical identity. A typical way of distinguishing themselves from German, French, and Italian composers was to employ the use of folk elements from their native lands. This resulted in a vast amount of piano literature that was rich in national idioms derived from folk traditions. The repertoire reflected many different national styles and trends. Due to the many beautiful, brilliant, virtuosic, and profound ideas that composers infused into these nationalistic works, they took their rightful place in the standard piano repertoire. Depending on the compositional background or style of the individual composers, folk elements were presented in a wide variety of ways. For example, Bartók recorded many short examples collected from the Hungarian countryside and used these melodies to influence his compositional style. Many composers enhanced and expanded piano technique. Liszt, in his Hungarian Rhapsodies, emphasized rhythmic vitality and virtuosic technique in extracting the essence of Hungarian folk themes. Chopin and Szymanowski also made use of rhythmic figurations in their polonaises and mazurkas, often making use of double-dotted rhythms. Obviously, composers made use of nationalistic elements to add to the piano literature and to expand the technique of the piano. This dissertation comprises three piano recitals presenting works of: Isaac Albeniz, Bela Bartók, Frédéric Chopin, Enrique Granados, Edvard Grieg, Franz Liszt, Frederic Rzewski, Alexander Scriabin, Karol Szymanowski, and Peter Ilich Tchaikovsky. -

1 Fons Sants Sagrera I Anglada Partitures I Documentació De Sants

Fons Sants Sagrera i Anglada Partitures i documentació de Sants Sagrera i Anglada Secció de Música Biblioteca de Catalunya 2019 SUMARI Identificació Context Contingut i estructura Condicions d’accés i ús Documentació relacionada Notes Control de la descripció Inventari IDENTIFICACIÓ Codi de referència: BC, Fons Sants Sagrera i Anglada Nivell de descripció: Fons Títol: Partitures i documentació de Sants Sagrera i Anglada Dates de creació: 1880-1980 Dates d’agregació: 1911-2005 Volum i suport de la unitat de descripció: 1,34 metres lineals (11 capses, 3.251 documents aproximadament): Documentació: - 17 àlbums (2252 unitats documentals aproximadament) - Col·leccions (391 programes, 19 publicacions periòdiques, 19 retalls de premsa, 6 fotografies, 9 caricatures i dibuixos, 3 nadales, 1 postal) - Documentació professional (6 unitats documentals) - Correspondència (2 unitats documentals) - Documentació vària (23 unitats documentals) Partitures: - 520 unitats documentals aproximadament CONTEXT Nom del productor: Sants Sagrera i Anglada Notícia biogràfica: Sants Sagrera i Anglada (Girona, 1893 - Barcelona, 2 de gener de 1983). Violoncel·lista i pedagog. Començà els seus estudis musicals a l’Acadèmia d’Isidre i Tomàs Mollera a Girona. Posteriorment continuà els estudis de violoncel a l’Escola Municipal de Barcelona amb Josep Soler i Ventura. Més tard amplià la seva formació com a violoncel·lista amb Gaspar Cassadó i de música de cambra amb Joan Massià i Prats. 1 Principalment es dedicà a la interpretació d’obres de música de cambra, sent fundador junt amb altres músics de diferents formacions musicals, d’entre les quals cal remarcar les següents: el Quintet Català de Girona (ca. 1912), format per Josep Dalmau, Rafael Serra (violinistes), Josep Serra (violista), Sants Sagrera i Tomàs Mollera (pianista); el Trio Girona (ca. -

Orquestra De Cadaqués Josep Vicent, Director

Orquestra de Cadaqués Josep Vicent, director La Orquesta de Cadaqués se formó en 1988 con unos objetivos claros: trabajar de cerca Graduado Cum Laude en el Conservatorio de Alicante y en el Amsterdam con los compositores contemporáneos vivos, recuperar un legado de música española Conservatory. Fue asistente de Alberto Zedda y Daniel Barenboim. Recibe el Primer olvidada e impulsar la carrera de solistas, compositores y directores emergentes. Premio de Interpretación de Juventudes Musicales, el Premio Vicente Monfort de las Júlia Gállego, solista Sir Neville Marriner, Gennady Rozhdestvensky o Philippe Entremont se convirtieron en Artes Ciudad de Valencia 2013 y el Premio Óscar Esplá Ciudad de Alicante. Es principales invitados, así como Alicia de Larrocha, Victoria de los Ángeles, Teresa Embajador Internacional de la “Fundación Cultura de Paz” presidida por D. Federico Berganza, Paco de Lucía, Ainhoa Arteta, Jonas Kaufmann, Olga Borodina y Juan Diego Mayor Zaragoza. Premio Los Mejores Diario LA VERDAD 2016. Excepcional solista Alicantina, fue miembro de la Joven Orquesta Nacional de Florez entre otros. Tras una amplia y temprana carrera como Solista-Director Artístico y su trabajo en la España y de la Gustav Mahler Jugendorchester, flauta Principal de la Oquesta En 1992 la orquesta impulsó el Concurso Internacional de Dirección. Pablo González, Orquesta del Concertgebouw (1998- 2004), inicia una imparable carrera internacional Sinfónica de Tenerife y de la Orquesta Sinfónica de Galicia. Galardonada con Gianandrea Noseda, Vasily Petrenko o Michal Nesterowicz han sido algunos de los frente a formaciones como: London Symphony, The World Orchestra, Paris Chamber el Premio de la Ciudad de París en 1994, el Primer Premio en el concurso de ganadores. -

La Academia Granados-Marshall Y Su Contribución a La Consolidación De La Técnico-Pedagogía Española: Actividad Y Rendimiento Entre 1945 Y 19551

LA ACADEMIA GRANADOS-MARSHALL Y SU CONTRIBUCIÓN A LA CONSOLIDACIÓN DE LA TÉCNICO-PEDAGOGÍA ESPAÑOLA: ACTIVIDAD Y RENDIMIENTO ENTRE 1945 Y 19551. Por Aida Velert Hernández 1 La información que ofrezco en este artículo procede del Trabajo Fin de Grado Superior en la Especialidad de Piano inédito que realicé bajo la dirección de la dra. Victoria Alemany y presenté al Departamento de Instrumentos Polifónicos del Conservatorio Superior de Música “Joaquín Rodrigo” de Valencia en 2013 [Velert (2013)]. Descubrí la Academia Marshall el curso 2003-2004, cuando iba a cumplir catorce años y fui aceptada como alumna en dicho centro sin ser en absoluto consciente al principio de su prestigio, y poco a poco me fue fascinando lentamente. Una entidad que ha sido capaz de mantenerse firme e imperturbable durante más de una centuria, que ha sido testigo directo de los cambios/transformaciones sociopolíticas2 y económicas del país resistiendo embistes y contratiempos, y que ha logrado formar a algunos de los pianistas más relevantes del siglo XX en España, estimo que merece ser estudiada en profundidad. En definitiva, decidí abordar la investigación sobre un período de la existencia de esta academia en mi Trabajo Fin de Grado Superior por el respeto y la admiración que siento hacia esta institución, que se han ido acrecentando con el paso del tiempo. Facilitó mi tarea contar con abundante información aportada gentilmente por el Centro Documental de la Academia Marshall (CEDAM), por lo que quiero en primer lugar agradecer sinceramente al personal de administración de la Academia, y en especial a su directora de gestión doña Cintia Matamoros3, su confianza y la inestimable ayuda que me han brindado de forma desinteresada en todo momento. -

Music in Catalonia Today

MUSIC MUSIC IN CATALONIA TODAY CATALONIA'S MOST CHARACTERISTIC CONTRIBUTION TO UNIVERSAL MUSIC HAS BEEN ITS REPERTORY OF FOLKSONGS, ONE OF THE MOST BEAUTIFUL AND RICHEST IN EUROPE.IN CLASSICAL MUSIC, ALONGSIDE QUITE OUTSTANDING COMPOSERS, THERE IS AN EXTRAORDINARY LIST OF FIRST-RATE INTERNATIONAL PERFORMERS. SEBASTIA BENET I SANVICENS MUSICOLOGIST he music scene in Catalonia to- there is an extraordinary list of first-rate end of the nineteenth century. The mu- day has a remote ancestry which intemational performers. sic is played by a special band, the co- has fashioned its character down Pau Casals, father of the modern cello, bla, led by the tenora, an instrument to the present moment. In the course of contributed to a universal knowledge of which originated in Catalonia. The sar- this evolution we see that Catalonia's Catalan folk music by adopting the dana is a living dance, which people of most characteristic contribution to uni- beautiful tune "El cant dels ocells" as a al1 ages take part in at any celebration versal music has been its repertory of testimony of his cultural origin. Our during the year, and which has pro- folksongs, one of the most beautiful and popular music also includes a wide va- duced masterpieces composed by some richest in Europe. In classical music, riety of dances, in particular the sarda- of the best Catalan musicians, includ- alongside quite outstanding composers, na, Catalonia's national dance since the ing Pau Casals himself. Igor Stravinsky, MUSIC on a visit to Barcelona in 1924, was 1927-, which had a primarily classical recently, the conductors Salvador Mas filled with enthusiasm for a sardana repertoire and soon took their place in and Josep Pons, successful internatio- with music by Juli Garreta, a musician the European choral movement. -

A La Cubana: Enrique Granados's Cuban Connection

UC Riverside Diagonal: An Ibero-American Music Review Title A la cubana: Enrique Granados’s Cuban Connection Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/90b4c4cb Journal Diagonal: An Ibero-American Music Review, 2(1) ISSN 2470-4199 Author de la Torre, Ricardo Publication Date 2017 DOI 10.5070/D82135893 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California A la cubana: Enrique Granados’s Cuban Connection RICARDO DE LA TORRE Abstract Cuba exerted a particular fascination on several generations of Spanish composers. Enrique Granados, himself of Cuban ancestry, was no exception. Even though he never set foot on the island—unlike his friend Isaac Albéniz—his acquaintance with the music of Cuba became manifest in the piano piece A la cubana, his only work with overt references to that country. This article proposes an examination of A la cubana that accounts for the textural and harmonic characteristics of the second part of the piece as a vehicle for Granados to pay homage to the piano danzas of Cuban composer Ignacio Cervantes. Also discussed are similarities between A la cubana and one of Albéniz’s own piano pieces of Caribbean inspiration as well as the context in which the music of then colonial Cuba interacted with that of Spain during Granados’s youth, paying special attention to the relationship between Havana and Catalonia. Keywords: Granados, Ignacio Cervantes, Havana, Catalonia, Isaac Albéniz, Cuban-Spanish musical relations Resumen Varias generaciones de compositores españoles sintieron una fascinación particular por Cuba. Enrique Granados, de ascendencia cubana, no fue la excepción.