A La Cubana: Enrique Granados's Cuban Connection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Senior Researcher on Food Technology

SENIOR RESEARCHER ON FOOD TECHNOLOGY About IRTA IRTA is a research institute owned by the Government of Catalonia ascribed to the Department of Agriculture and Livestock. It is regulated by Law 04/2009, passed by the Catalan Parliament on 15 April 2009, and it is ruled by private regulations. IRTA is one of the CERCA centers of excellence of the Catalan Research System. IRTA’s purpose is to contribute to the modernization, competitiveness and sustainable development of agriculture, food and aquaculture sectors, the supply of healthy and quality foods for consumers and, generally, improving the welfare and prosperity of the society. THE PROGRAM OF FOOD TECHNOLOGY This Program is focused on answering the technological and research requirements of the agro-food industry. It has three main research lines: Food Engineering, Processes in the food industry, New process technologies. The Food Engineering research line works on: modelling transformation processes of food; transport operations (mass, heat and quantity of movement); process simulation and control; process engineering. Their scopes are: Drying Engineering studies the optimization of the traditional processes and the development of new drying systems. Optimization of traditional processes works in the modelling of mass transfer processes and transformation kinetics of foods in order to enhance their quality and energetic efficiency. New Technologies Engineering studies food packaging, transformation and preservation. Control systems are applied to raw material, processes and products The Processes in the Food Industry research line focuses on the improvement of traditional technologies in order to enhance quality, safety and sensorial characteristics of the product or the efficiency of the process. -

Beyond Salsa Bass the Cuban Timba Revolution

BEYOND SALSA BASS THE CUBAN TIMBA REVOLUTION VOLUME 1 • FOR BEGINNERS FROM CHANGÜÍ TO SON MONTUNO KEVIN MOORE audio and video companion products: www.beyondsalsa.info cover photo: Jiovanni Cofiño’s bass – 2013 – photo by Tom Ehrlich REVISION 1.0 ©2013 BY KEVIN MOORE SANTA CRUZ, CA ALL RIGHTS RESERVED No part of this publication may be reproduced in whole or in part, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording or otherwise, without written permission of the author. ISBN‐10: 1482729369 ISBN‐13/EAN‐13: 978‐148279368 H www.beyondsalsa.info H H www.timba.com/users/7H H [email protected] 2 Table of Contents Introduction to the Beyond Salsa Bass Series...................................................................................... 11 Corresponding Bass Tumbaos for Beyond Salsa Piano .................................................................... 12 Introduction to Volume 1..................................................................................................................... 13 What is a bass tumbao? ................................................................................................................... 13 Sidebar: Tumbao Length .................................................................................................................... 1 Difficulty Levels ................................................................................................................................ 14 Fingering.......................................................................................................................................... -

Selected Intermediate-Level Solo Piano Music Of

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2005 Selected intermediate-level solo piano music of Enrique Granados: a pedagogical analysis Harumi Kurihara Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Kurihara, Harumi, "Selected intermediate-level solo piano music of Enrique Granados: a pedagogical analysis" (2005). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3242. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3242 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. SELECTED INTERMEDIATE-LEVEL SOLO PIANO MUSIC OF ENRIQUE GRANADOS: A PEDAGOGICAL ANALYSIS A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Harumi Kurihara B.M., Loyola University, New Orleans, 1993 M.M.,University of New Orleans, 1997 August, 2005 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my sincere appreciation to my major professor, Professor Victoria Johnson for her expert advice, patience, and commitment to my monograph. Without her help, I would not have been able to complete this monograph. I am also grateful to my committee members, Professors Jennifer Hayghe, Michael Gurt, and Jeffrey Perry for their interest and professional guidance in making this monograph possible. I must also recognize the continued encouragement and support of Professor Constance Carroll who provided me with exceptional piano instruction throughout my doctoral studies. -

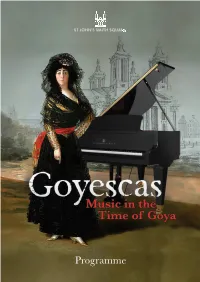

Music in the Time of Goya

Music in the Time of Goya Programme ‘Goyescas’: Music in the Time of Goya Some of the greatest names in classical music support the Iberian and Latin American Music Society with their membership 2 November 2016, 7.00pm José Menor piano Daniel Barenboim The Latin Classical Chamber Orchestra featuring: Argentine pianist, conductor Helen Glaisher-Hernández piano | Elena Jáuregui violin | Evva Mizerska cello Nicole Crespo O’Donoghue violin | Cressida Wislocki viola and ILAMS member with special guest soloists: Nina Corti choreography & castanets Laura Snowden guitar | Christin Wismann soprano Opening address by Jordi Granados This evening the Iberian and Latin American Music Society (ILAMS) pays tribute to one of Spain’s most iconic composers, Enrique Granados (1867–1916) on the centenary year of his death, with a concert programme inspired by Granados’ greatest muse, the great Spanish painter Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (1746–1828), staged amidst the Baroque splendour of St John’s Smith Square – a venue which, appropriately, was completed not long before Goya’s birth, in 1728. Enrique Granados To pay homage to Granados here in London also seems especially fi tting given that the great Composer spent his fi nal days on British shores. Granados Will you drowned tragically in the English Channel along with his wife Amparo after their boat, the SS Sussex, was torpedoed by the Germans. At the height of his join them? compositional powers, Granados had been en route to Spain from New York where his opera, Goyescas, had just received its world premiere, and where he had also given a recital for President Woodrow Wilson; in his lifetime Granados was known as much for his virtuoso piano playing as for his talent as a composer. -

Granados: Goyescas

Goyescas Enrique Granados 1. Los Requiebros [9.23] 2. Coloquio en La Reja [10.53] 3. El Fandango de Candil [6.41] 4. Quejas, ó la Maja y el Ruiseñor [6.22] 5. El Amor y la Muerte: Balada [12.43] 6. Epilogo: Serenata del Espectro [7.39] Total Timings [54.00] Ana-Maria Vera piano www.signumrecords.com The Goyescas suite has accompanied me throughout with her during the recording sessions and felt G my life, and I always knew that one day I would generous and grounded like never before. The music attempt to master it.The rich textures and came more easily as my perspectives broadened aspiring harmonies, the unfurling passion and I cared less about perfection. Ironically this is tempered by restraint and unforgiving rhythmic when you stand the best chance of approaching precision, the melancholy offset by ominous, dark your ideals and embracing your audience. humour, the elegance and high drama, the resignation and the hopefulness all speak to my sense of © Ana-Maria Vera, 2008 being a vehicle, offeeling the temperature changes, the ambiguity, and the emotion the way an actor might live the role of a lifetime. And so this particular project has meant more to me than almost any in my career. Catapulted into the limelight as a small child, I performed around the globe for years before realising I had never had a chance to choose a profession for myself. Early success, rather than going to my head, affected my self-confidence as a young adult and I began shying away from interested parties, feeling the attention wasn't deserved and therefore that it must be of the wrong kind. -

Beyond Salsa for Ensemble a Guide to the Modern Cuban Rhythm Section

BEYOND SALSA FOR ENSEMBLE A GUIDE TO THE MODERN CUBAN RHYTHM SECTION PIANO • BASS • CONGAS • BONGÓ • TIMBALES • DRUMS VOLUME 1 • EFECTOS KEVIN MOORE REVISION 1.0 ©2012 BY KEVIN MOORE SANTA CRUZ, CA ALL RIGHTS RESERVED No part of this publication may be reproduced in whole or in part, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording or otherwise, without written permission of the author. ISBN‐10: 146817486X ISBN‐13/EAN‐13: 978‐1468174861 www.timba.com/ensemble www.timba.com/piano www.timba.com/clave www.timba.com/audio www.timba.com/percussion www.timba.com/users/7 [email protected] cover design: Kris Förster based on photos by: Tom Ehrlich photo subjects (clockwise, starting with drummer): Bombón Reyes, Daymar Guerra, Miguelito Escuriola, Pupy Pedroso, Francisco Oropesa, Duniesky Baretto Table of Contents Introduction to the Beyond Salsa Series .............................................................................................. 12 Beyond Salsa: The Central Premise .................................................................................................. 12 How the Series is Organized and Sold .......................................................................................... 12 Book ......................................................................................................................................... 12 Audio ....................................................................................................................................... -

United States Consulate General Consular Section

United States Consulate General Consular Section Paseo Reina Elisenda, 23 - 08034 Barcelona, Spain Tel: (34) 93-280-22-27 - Fax: (34) 93-280-61-75 Email: [email protected] Web: Lawyers Engine Seach LIST OF ATTORNEYS ALL PRACTICES In the Consular District of Barcelona (As of February 2017) The Barcelona Consular District covers the provinces of Barcelona, Girona, Huesca, Lleida, Tarragona, Teruel, Zaragoza, and the Principality of Andorra. This list has been divided into sections, grouped by countries, autonomous communities, provinces and cities. The U.S. Consulate General in Barcelona, Spain assumes no responsibility or liability for the professional ability or reputation of, or the quality of services provided by, the following persons or firms. Inclusion on this list is in no way an endorsement by the Department of State or the U.S. Consulate in Barcelona. Names are listed alphabetically, and the order in which they appear has no other significance. The information in the list on professional credentials, areas of expertise and language ability is provided directly by the lawyers; the U.S. Consulate General in Barcelona is not in a position to vouch for such information. You may receive additional information about the individuals on the list by contacting the local bar association (or its equivalent) or the local licensing authorities. The Department of State (CA/OCS) has prepared an information sheet on retaining a foreign attorney that is available at this web site: Retaining a Foreign Attorney. Complaints should initially be addressed to the COLEGIO DE ABOGADOS (Bar Association) in the city involved; if you wish you may send a copy of the complaint to the U.S. -

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: NATIONAL

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: NATIONAL CHARACTER AS EXPRESSED IN PIANO LITERATURE Yong Sook Park, Doctor of Musical Arts, 2005 Dissertation directed by: Bradford Gowen, Professor of Music In the middle of the 19th century, many composers living outside of mainstream musical countries such as Germany and France attempted to establish their own musical identity. A typical way of distinguishing themselves from German, French, and Italian composers was to employ the use of folk elements from their native lands. This resulted in a vast amount of piano literature that was rich in national idioms derived from folk traditions. The repertoire reflected many different national styles and trends. Due to the many beautiful, brilliant, virtuosic, and profound ideas that composers infused into these nationalistic works, they took their rightful place in the standard piano repertoire. Depending on the compositional background or style of the individual composers, folk elements were presented in a wide variety of ways. For example, Bartók recorded many short examples collected from the Hungarian countryside and used these melodies to influence his compositional style. Many composers enhanced and expanded piano technique. Liszt, in his Hungarian Rhapsodies, emphasized rhythmic vitality and virtuosic technique in extracting the essence of Hungarian folk themes. Chopin and Szymanowski also made use of rhythmic figurations in their polonaises and mazurkas, often making use of double-dotted rhythms. Obviously, composers made use of nationalistic elements to add to the piano literature and to expand the technique of the piano. This dissertation comprises three piano recitals presenting works of: Isaac Albeniz, Bela Bartók, Frédéric Chopin, Enrique Granados, Edvard Grieg, Franz Liszt, Frederic Rzewski, Alexander Scriabin, Karol Szymanowski, and Peter Ilich Tchaikovsky. -

Creolizing Contradance in the Caribbean

Peter Manuel 1 / Introduction Contradance and Quadrille Culture in the Caribbean region as linguistically, ethnically, and culturally diverse as the Carib- bean has never lent itself to being epitomized by a single music or dance A genre, be it rumba or reggae. Nevertheless, in the nineteenth century a set of contradance and quadrille variants flourished so extensively throughout the Caribbean Basin that they enjoyed a kind of predominance, as a common cultural medium through which melodies, rhythms, dance figures, and per- formers all circulated, both between islands and between social groups within a given island. Hence, if the latter twentieth century in the region came to be the age of Afro-Caribbean popular music and dance, the nineteenth century can in many respects be characterized as the era of the contradance and qua- drille. Further, the quadrille retains much vigor in the Caribbean, and many aspects of modern Latin popular dance and music can be traced ultimately to the Cuban contradanza and Puerto Rican danza. Caribbean scholars, recognizing the importance of the contradance and quadrille complex, have produced several erudite studies of some of these genres, especially as flourishing in the Spanish Caribbean. However, these have tended to be narrowly focused in scope, and, even taken collectively, they fail to provide the panregional perspective that is so clearly needed even to comprehend a single genre in its broader context. Further, most of these pub- lications are scattered in diverse obscure and ephemeral journals or consist of limited-edition books that are scarcely available in their country of origin, not to mention elsewhere.1 Some of the most outstanding studies of individual genres or regions display what might seem to be a surprising lack of familiar- ity with relevant publications produced elsewhere, due not to any incuriosity on the part of authors but to the poor dissemination of works within (as well as 2 Peter Manuel outside) the Caribbean. -

Mapping Urban Water Governance Models in the Spanish Mediterranean Coastline

Water and Society IV 75 MAPPING URBAN WATER GOVERNANCE MODELS IN THE SPANISH MEDITERRANEAN COASTLINE RUBÉN VILLAR & ANA ARAHUETES Instituto Interuniversitario de Geografía, Universidad de Alicante, Spain ABSTRACT The heterogeneity of governance and management models of municipal water supply in the Spanish Mediterranean coastline has increased in recent decades. This diversity is explained by the increase of private companies responsible for the management of the local water service and the presence of supramunicipal public entities responsible for water catchment, treatment and distribution to the municipalities. Based on the review of the existing literature, the information available on the websites of the leading corporate groups in the water sector and contacting with councils, the companies and supramunicipal entities involved in the service of municipal water in the Mediterranean coastline have been identified. The objective of this work is to analyse the territorial presence of the main actors in the urban water management through its cartographic representation, as well as analyse its ownership and importance in terms of population supplied. This analysis shows a high presence of companies belonging to the AGBAR group that supply around half of the total population in the Spanish coastline municipalities. Likewise, there is a regional specialization of certain private companies that concentrate the urban water management for the most part of the coastline municipalities. This is the case of FACSA, which manages the water services in 87% of coastline municipalities in Castellón, or Hidraqua in Alicante, that operates in the 65%. Furthermore, the presence of large supramunicipal public entities is widespread along the coastline, especially in Catalonia and the southeast. -

Carrilet I Greenway (Girona)

Carrilet I Greenway Until the sixties, the Girona-Olot railway was the main transport artery for the rural districts of La Garrotxa, La Selva, and El Gironés. A modest narrow gauge railway (of the type known as "carrilet" in Cataluña) just 54 Kms long, it ran along the banks of the rivers Ter, Bruguent, and Fluvià in the shadow of the menacing La Garrotxa volcanoes. In the not to distant future, this Greenway is to be linked by a track to the Camí de Ferro Greenway de (12 Kms between Ripoll and Sant Joan de les Abadesses). Add on the existing Girona-Costa Brava Greenway between Girona and San Feliú de Guíxols (39 Kms) and we can travel by Greenway from the upper Pyrenees to the Mediterranean, a distance of nearly 135 Km. TECHNICAL DATA CONDITIONED GREENWAY A refreshing itinerary through the shades of the old volcanoes of Garrotxa. LOCATION Between Olot and Girona GIRONA Length: 54 km Users: * * Amer-El Pastoral: Part with steep slopes (there is alternative that runs through the road, 2Km) Type of surface: Conditioned earth Natural landscape: Garrotxa Volcanic park. Banks of rivers Ter and Fluviá Cultural Heritage: Urban centres of Angles, Sant Feliú and Girona. Romanic chapels. D´Hostoles Castle Infrastructure: Greenway. 12 bridges How to get there: Girona: Medium and long distance Renfe lines (*) Please ask the conditions of bike admittance in Renfe trains Olot: Teisa Bus company Connections: Barcelona: 130 Kms. to Girona. Maps: Military map os spain. 1:50.000 scale 256, 257, 294, 295, 333 y 334sheets Official road map of the Ministry of Public Works (Ministerio de Fomento) More information on Spanish Greenways Travel Guides, Volume 1 From Girona also departs the Carrilet II Greenway DESCRIPTION Km. -

CYCLE TOURING in Spain

CYCLE TOURING in Spain www.spain.info CYCLE TOURING IN SPAIN CONTENTS Introduction 3 Greenway cycling routes 5 Senda del Oso Greenway cycling route Greenway cycling route along the Vasco Navarro railway Greenway cycling routes in Girona Oja River Greenway cycling route Eresma Valley Greenway cycling route Ojos Negro Greenway cycling route Tajuña Greenway cycling route Sierra de Alcaraz Greenway cycling route Northwest Greenway cycling route El Aceite Greenway cycling route Manacor-Artá Greenway cycling route 10 bike-friendly cities 12 Donostia/San Sebastián Vitoria-Gasteiz Zaragoza Gijón Albacete Seville Barcelona Valencia Ministry of Industry, Commerce and Tourism Palma de Mallorca Published by: © Turespaña Cordoba Created by: Lionbridge NIPO: Great routes for enjoying 19 nature and culture FREE COPY The Way of Saint James The content of this leaflet has been created with the utmost care. However, if you find an error, Silver Route please help us to improve by sending an email to Extremadura brochures@tourspain. es The TransAndalus Front Page: Puig Major, Majorca The Transpirenaica Back: Madrid Río The Way of El Cid The Route of Don Quixote Castilla Canal Eurovelo routes in Spain Other routes 2 Practical information 27 Whether you're on a road INTRODUCTION bike or a mountain bike Photo: csp/123rf. com Photo: csp/123rf. Spain invites you to come and discover it in your own a BARCELONA way and at your own pace. If you love cycling, then Spain is the routes. What's more, along the way place for you. You'll have the chance to you'll find all types of accommodation, explore beautiful landscapes, towns, specialist companies and hiring options.