Inspiration and Influence Behind the Keyboard Styles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

El Flamenco Del Siglo XIX: Entre Lo Andaluz, Lo Gitano Y Lo Clásico

Fotografía. Café cantante del Burrero (©Emilio Beauchy Cano, ca. 1880) x23 diciembre estreno El flamenco del siglo XIX: entre lo andaluz, lo gitano y lo clásico Lo que a partir de 1847 conocemos como flamenco empieza a formarse a finales del siglo XVIII como reacción a la música italiana y francesa que se imponía desde los ambientes académicos. Unas cuantas familias gitanas de la bahía de Cádiz comienzan a interpretar con entonaciones inéditas las canciones populares andaluzas, pero también españolas y transatlánticas. Esta doble vertiente gitana y andaluza se complementa con la guitarra, que se nutre a su vez de lo popular y lo clásico. Lo mismo sucede con el baile, perfecta síntesis de maneras gitanas y boleras. Desde 1865 el género encuentra gran difusión en los cafés cantantes hasta finales de la centuria, cuando se inician las grabaciones en cilindros de cera y discos de pizarra, soporte con el que el flamenco inicia una nueva etapa en el siglo xx. Estos repertorios los escucharemos en El flamenco del siglo XIX: entre lo andaluz, lo gitano y lo clásico. Cante Nuria Martín, Bonela y David Carpio Cante y guitarra Sergio Cuesta ‘El Hombrecillo’ Guitarra Chaparro de Málaga, Francisco Vinuesa y la colaboración especial de Rafael Riqueni Guitarra clásica Davinia Ballesteros Violín Pepe Molina Baile Carmen Ríos y Cristóbal García Palmas Fernando Santiago Voz en off Fran Perea Ayudante de dirección Marina Perea Dirección documental y artística Ramón Soler Díaz Producción Teatro Cervantes de Málaga Con la colaboración de Museo Carmen Thyssen Málaga I Violín y guitarra por verdiales (tradicional). Pepe Molina y Sergio Cuesta ‘El Hombrecillo’ Toná del Brujo, corrido de los Puertos y alboreás (tradicional). -

Selected Intermediate-Level Solo Piano Music Of

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2005 Selected intermediate-level solo piano music of Enrique Granados: a pedagogical analysis Harumi Kurihara Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Kurihara, Harumi, "Selected intermediate-level solo piano music of Enrique Granados: a pedagogical analysis" (2005). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3242. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3242 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. SELECTED INTERMEDIATE-LEVEL SOLO PIANO MUSIC OF ENRIQUE GRANADOS: A PEDAGOGICAL ANALYSIS A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Harumi Kurihara B.M., Loyola University, New Orleans, 1993 M.M.,University of New Orleans, 1997 August, 2005 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my sincere appreciation to my major professor, Professor Victoria Johnson for her expert advice, patience, and commitment to my monograph. Without her help, I would not have been able to complete this monograph. I am also grateful to my committee members, Professors Jennifer Hayghe, Michael Gurt, and Jeffrey Perry for their interest and professional guidance in making this monograph possible. I must also recognize the continued encouragement and support of Professor Constance Carroll who provided me with exceptional piano instruction throughout my doctoral studies. -

Rhythmic Foundation and Accompaniment

Introduction To Flamenco: Rhythmic Foundation and Accompaniment by "Flamenco Chuck" Keyser P.O. Box 1292 Santa Barbara, CA 93102 [email protected] http://users.aol.com/BuleriaChk/private/flamenco.html © Charles H. Keyser, Jr. 1993 (Painting by Rowan Hughes) Flamenco Philosophy IA My own view of Flamenco is that it is an artistic expression of an intense awareness of the existential human condition. It is an effort to come to terms with the concept that we are all "strangers and afraid, in a world we never made"; that there is probably no higher being, and that even if there is he/she (or it) is irrelevant to the human condition in the final analysis. The truth in Flamenco is that life must be lived and death must be faced on an individual basis; that it is the fundamental responsibility of each man and woman to come to terms with their own alienation with courage, dignity and humor, and to support others in their efforts. It is an excruciatingly honest art form. For flamencos it is this ever-present consciousness of death that gives life itself its meaning; not only as in the tragedy of a child's death from hunger in a far-off land or a senseless drive-by shooting in a big city, but even more fundamentally in death as a consequence of life itself, and the value that must be placed on life at each moment and on each human being at each point in their journey through it. And it is the intensity of this awareness that gave the Gypsy artists their power of expression. -

A Comparison of the Piano and Guitar Versions of Isaac Albéniz's Spanish Suite Op

A COMPARISON OF THE PIANO AND GUITAR VERSIONS OF ISAAC ALBÉNIZ'S SPANISH SUITE OP. 47 by YI-YIN CHIEN A LECTURE-DOCUMENT Presented to the School of Music and Dance of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts November 2016 2 “A Comparison of the Piano and Guitar Versions of Isaac Albéniz’s Spanish Suite, Op. 47’’ a document prepared by Yi-Yin Chien in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Musical Arts degree in the School of Music and Dance. This document has been approved and accepted by: Jack Boss, Chair of the Examining Committee Date: November 20th, 2016 Committee in Charge: Dr. Jack Boss, Chair Dr. Juan Eduardo Wolf Dr. Dean Kramer Accepted by: Director of Graduate Studies, School of Music and Dance © 2016 Yi-Yin Chien 3 CURRICULUM VITAE NAME OF AUTHOR: Yi-Yin Chien PLACE OF BIRTH: Taiwan DATE OF BIRTH: November 02, 1986 GRADUATE AND UNDERGRADUATE SCHOOLS ATTENDED: University of Oregon, School of Music and Dance Peabody Institute of the Johns Hopkins University Tainan National University of Arts DEGREES AWARDED: Doctor of Musical Arts, 2016, University of Oregon Master of Music, 2011, Peabody Institute of the Johns Hopkins University Bachelor of Music, 2009, Tainan National University of Arts AREAS OF SPECIAL INTEREST: Piano Pedagogy Music Theory PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE: College Piano Teaching, University of Oregon, School of Music and Dance, 09/2014 - 06/2015 Taught piano lessons for music major and non-major college students Graduate Teaching -

Pdf (Boe-A-2021-8027

BOLETÍN OFICIAL DEL ESTADO Núm. 115 Viernes 14 de mayo de 2021 Sec. III. Pág. 57801 III. OTRAS DISPOSICIONES COMUNIDAD AUTÓNOMA DE EXTREMADURA 8027 Resolución de 24 de noviembre de 2020, de la Consejería de Cultura, Turismo y Deportes, por la que se incoa expediente de declaración de bien de interés cultural a favor del «Flamenco en Extremadura», en la categoría de patrimonio cultural inmaterial. El Estatuto de Autonomía de Extremadura, aprobado mediante Ley Orgánica 1/1983, de 25 de febrero, y modificado mediante Ley Orgánica 1/2011, de 28 de enero, la cual se publicó y entró en vigor con fecha 29 de enero de 2011, recoge como competencia exclusiva en su artículo 9.1.47 la «Cultura en cualquiera de sus manifestaciones», así como el «Patrimonio Histórico y Cultural de interés para la Comunidad Autónoma». En desarrollo de esta competencia se dictó la Ley 2/1999, de 29 de marzo, de Patrimonio Histórico y Cultural de Extremadura. El artículo 1.2 de la norma determina que «constituyen el Patrimonio Histórico y Cultural de Extremadura todos los bienes tanto materiales como intangibles que, por poseer un interés artístico, histórico, arquitectónico, arqueológico, paleontológico, etnológico, científico, técnico, documental y bibliográfico, sean merecedores de una protección y una defensa especiales. También forman parte del mismo los yacimientos y zonas arqueológicas, los sitios naturales, jardines y parques que tengan valor artístico, histórico o antropológico, los conjuntos urbanos y elementos de la arquitectura industrial, así como la rural o popular y las formas de vida y su lenguaje que sean de interés para Extremadura». -

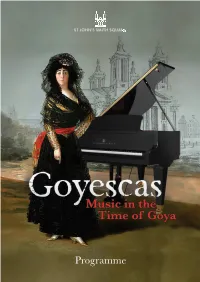

Music in the Time of Goya

Music in the Time of Goya Programme ‘Goyescas’: Music in the Time of Goya Some of the greatest names in classical music support the Iberian and Latin American Music Society with their membership 2 November 2016, 7.00pm José Menor piano Daniel Barenboim The Latin Classical Chamber Orchestra featuring: Argentine pianist, conductor Helen Glaisher-Hernández piano | Elena Jáuregui violin | Evva Mizerska cello Nicole Crespo O’Donoghue violin | Cressida Wislocki viola and ILAMS member with special guest soloists: Nina Corti choreography & castanets Laura Snowden guitar | Christin Wismann soprano Opening address by Jordi Granados This evening the Iberian and Latin American Music Society (ILAMS) pays tribute to one of Spain’s most iconic composers, Enrique Granados (1867–1916) on the centenary year of his death, with a concert programme inspired by Granados’ greatest muse, the great Spanish painter Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (1746–1828), staged amidst the Baroque splendour of St John’s Smith Square – a venue which, appropriately, was completed not long before Goya’s birth, in 1728. Enrique Granados To pay homage to Granados here in London also seems especially fi tting given that the great Composer spent his fi nal days on British shores. Granados Will you drowned tragically in the English Channel along with his wife Amparo after their boat, the SS Sussex, was torpedoed by the Germans. At the height of his join them? compositional powers, Granados had been en route to Spain from New York where his opera, Goyescas, had just received its world premiere, and where he had also given a recital for President Woodrow Wilson; in his lifetime Granados was known as much for his virtuoso piano playing as for his talent as a composer. -

Granados: Goyescas

Goyescas Enrique Granados 1. Los Requiebros [9.23] 2. Coloquio en La Reja [10.53] 3. El Fandango de Candil [6.41] 4. Quejas, ó la Maja y el Ruiseñor [6.22] 5. El Amor y la Muerte: Balada [12.43] 6. Epilogo: Serenata del Espectro [7.39] Total Timings [54.00] Ana-Maria Vera piano www.signumrecords.com The Goyescas suite has accompanied me throughout with her during the recording sessions and felt G my life, and I always knew that one day I would generous and grounded like never before. The music attempt to master it.The rich textures and came more easily as my perspectives broadened aspiring harmonies, the unfurling passion and I cared less about perfection. Ironically this is tempered by restraint and unforgiving rhythmic when you stand the best chance of approaching precision, the melancholy offset by ominous, dark your ideals and embracing your audience. humour, the elegance and high drama, the resignation and the hopefulness all speak to my sense of © Ana-Maria Vera, 2008 being a vehicle, offeeling the temperature changes, the ambiguity, and the emotion the way an actor might live the role of a lifetime. And so this particular project has meant more to me than almost any in my career. Catapulted into the limelight as a small child, I performed around the globe for years before realising I had never had a chance to choose a profession for myself. Early success, rather than going to my head, affected my self-confidence as a young adult and I began shying away from interested parties, feeling the attention wasn't deserved and therefore that it must be of the wrong kind. -

Coastal Iberia

distinctive travel for more than 35 years TRADE ROUTES OF COASTAL IBERIA UNESCO Bay of Biscay World Heritage Site Cruise Itinerary Air Routing Land Routing Barcelona Palma de Sintra Mallorca SPAIN s d n a sl Lisbon c I leari Cartagena Ba Atlantic PORTUGALSeville Ocean Granada Mediterranean Málaga Sea Portimão Gibraltar Seville Plaza Itinerary* This unique and exclusive nine-day itinerary and small ship u u voyage showcases the coastal jewels of the Iberian Peninsula Lisbon Portimão Gibraltar between Lisbon, Portugal, and Barcelona, Spain, during Granada u Cartagena u Barcelona the best time of year. Cruise ancient trade routes from the October 3 to 11, 2020 Atlantic Ocean to the Mediterranean Sea aboard the Day exclusively chartered, Five-Star LE Jacques Cartier, featuring 1 Depart the U.S. or Canada the extraordinary Blue Eye, the world’s first multisensory, underwater Observation Lounge. This state-of-the-art small 2 Lisbon, Portugal/Embark Le Jacques Cartier ship, launching in 2020, features only 92 ocean-view Suites 3 Portimão, the Algarve, for Lagos and Staterooms and complimentary alcoholic and nonalcoholic beverages and Wi-Fi throughout the ship. Sail up Spain’s 4 Cruise the Guadalquivir River into legendary Guadalquivir River, “the great river,” into the heart Seville, Andalusia, Spain of beautiful Seville, an exclusive opportunity only available 5 Gibraltar, British Overseas Territory on this itinerary and by small ship. Visit Portugal’s Algarve region and Granada, Spain. Stand on the “Top of the Rock” 6 Málaga for Granada, Andalusia, Spain to see the Pillars of Hercules spanning the Strait of Gibraltar 7 Cartagena and call on the Balearic Island of Mallorca. -

The Barzakh of Flamenco: Tracing the Spirituality, Locality and Musicality of Flamenco from South of the Strait of Gibraltar

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Fall 2011 The aB rzakh of Flamenco: Tracing the Spirituality, Locality and Musicality of Flamenco From South of the Strait of Gibraltar Tania Flores SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Dance Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, and the Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons Recommended Citation Flores, Tania, "The aB rzakh of Flamenco: Tracing the Spirituality, Locality and Musicality of Flamenco From South of the Strait of Gibraltar" (2011). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 1118. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/1118 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Barzakh of Flamenco: Tracing the Spirituality, Locality and Musicality of Flamenco from South of the Strait of Gibraltar Tania Flores Occidental College Migration and Transnational Identity: Fall 2011 Flores 2 Acknowledgments I could not have completed this project without the advice and guidance of my academic director, Professor Souad Eddouada; my advisor, Professor Taieb Belghazi; my professor of music at Occidental College, Professor Simeon Pillich; my professor of Islamic studies at Occidental, Professor Malek Moazzam-Doulat; or my gracious and helpful interviewees. I am also grateful to Elvira Roca Rey for allowing me to use her studio to choreograph after we had finished dance class, and to Professor Said Graiouid for his guidance and time. -

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: NATIONAL

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: NATIONAL CHARACTER AS EXPRESSED IN PIANO LITERATURE Yong Sook Park, Doctor of Musical Arts, 2005 Dissertation directed by: Bradford Gowen, Professor of Music In the middle of the 19th century, many composers living outside of mainstream musical countries such as Germany and France attempted to establish their own musical identity. A typical way of distinguishing themselves from German, French, and Italian composers was to employ the use of folk elements from their native lands. This resulted in a vast amount of piano literature that was rich in national idioms derived from folk traditions. The repertoire reflected many different national styles and trends. Due to the many beautiful, brilliant, virtuosic, and profound ideas that composers infused into these nationalistic works, they took their rightful place in the standard piano repertoire. Depending on the compositional background or style of the individual composers, folk elements were presented in a wide variety of ways. For example, Bartók recorded many short examples collected from the Hungarian countryside and used these melodies to influence his compositional style. Many composers enhanced and expanded piano technique. Liszt, in his Hungarian Rhapsodies, emphasized rhythmic vitality and virtuosic technique in extracting the essence of Hungarian folk themes. Chopin and Szymanowski also made use of rhythmic figurations in their polonaises and mazurkas, often making use of double-dotted rhythms. Obviously, composers made use of nationalistic elements to add to the piano literature and to expand the technique of the piano. This dissertation comprises three piano recitals presenting works of: Isaac Albeniz, Bela Bartók, Frédéric Chopin, Enrique Granados, Edvard Grieg, Franz Liszt, Frederic Rzewski, Alexander Scriabin, Karol Szymanowski, and Peter Ilich Tchaikovsky. -

UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Fleeing Franco’s Spain: Carlos Surinach and Leonardo Balada in the United States (1950–75) Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5rk9m7wb Author Wahl, Robert Publication Date 2016 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Fleeing Franco’s Spain: Carlos Surinach and Leonardo Balada in the United States (1950–75) A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music by Robert J. Wahl August 2016 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Walter A. Clark, Chairperson Dr. Byron Adams Dr. Leonora Saavedra Copyright by Robert J. Wahl 2016 The Dissertation of Robert J. Wahl is approved: __________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________ Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements I would like to thank the music faculty at the University of California, Riverside, for sharing their expertise in Ibero-American and twentieth-century music with me throughout my studies and the dissertation writing process. I am particularly grateful for Byron Adams and Leonora Saavedra generously giving their time and insight to help me contextualize my work within the broader landscape of twentieth-century music. I would also like to thank Walter Clark, my advisor and dissertation chair, whose encouragement, breadth of knowledge, and attention to detail helped to shape this dissertation into what it is. He is a true role model. This dissertation would not have been possible without the generous financial support of several sources. The Manolito Pinazo Memorial Award helped to fund my archival research in New York and Pittsburgh, and the Maxwell H. -

DE PLAYERAS Y SEGUIDILLAS La Seguiriya Y Su Legendario Nacimiento

DE PLAYERAS y SEGUIDILLAS La Seguiriya y su legendario nacimiento Guillermo Castro Buendía Musicólogo especializado en Flamenco Introducción En el flamenco, parece que nunca está dicha la última palabra en materia de investigación. En pleno siglo XXI, a nosotros todavía nos asaltan dudas en aspectos relacionados con el origen musical de algunos palos, sobre todo de los primeros en formarse: es el caso de la seguiriya. En este trabajo vamos a hacer un análisis de las músicas que sirvieron de soporte a los diferentes tipos estróficos cultivados en la seguiriya, para intentar comprender el origen musical y desarrollo de este singular e importante estilo, uno de los puntales del género flamenco. Para ello utilizaremos los documentos musicales que hemos podido encontrar desde principios del siglo XIX, época aún preflamenca, hasta principios del siglo XX, momento en que la seguiriya ya se encontraba plenamente definida y estructurada desde el punto de vista flamenco. Igualmente, realizaremos un profuso estudio de los metros que aparecen en la seguiriya, siendo éste un aspecto muy particular e importante –creemos nosotros– dentro de la transmisión oral y, en particular, de este estilo flamenco. Recomendamos la impresión de este extenso trabajo para una mayor comodidad de lectura. Hemos incluido un índice al final (pág. 150) para facilitar el acceso a los diferentes puntos del mismo. Preliminares ―Lo flamenco‖ Uno de los problemas que arrastra el flamenco en su faceta de investigación es la propia definición de ―lo flamenco‖, y su aplicación en las distintas etapas que como arte ha venido desarrollando. Es evidente que ―lo flamenco‖ desde el punto de vista musical, no fue igual a mediados del siglo XIX que a finales, o ya entrado el siglo XX, y no digamos en las últimas décadas del pasado siglo.