Santurce San Juan, Puerto Rico

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Informe Final Evolución Del Plan Maestro Y Las Extensiones Al Tren Urbano

Programa de Desarrollo Profesional UPR/PUPR/ATI División Grupo PUPR Informe Final Evolución del Plan Maestro y las Extensiones al Tren Urbano Mentores: Prof. Amado Vélez Gallego, M.S.C.E., P.E. [email protected] Prof. Felipe Luyanda Villafañe, Dr.Eng., P.E. [email protected] Gustavo E. Pacheco Crosetti, Ph. D., P.E. [email protected] Sometido por: Carlos J. Rodríguez Bury [email protected] Universidad Politécnica de Puerto Rico Ave. Ponce de León, Hato Rey, Puerto Rico Departamento de Ingeniería Civil y Ambiental 17 de mayo de 2008 Prefacio Esta investigación consiste en el estudio de la evolución del plan maestro del Tren Urbano (PMTU), desde sus comienzos en la década del 1960 hasta el presente y las extensiones del mismo hoy día. Se desarrollo una recopilación de información de los estudios previos seleccionados al plan maestro del tren urbano (TU) y sus extensiones, de manera de proveer una sola fuente en la cual la comunidad profesional y el gobierno puedan ver las diferentes ideas asociadas al TU en un solo documento. 2 Tabla de Contenido 1. Introducción .................................................................................. 4 1.1 Tema de Investigación ................................................................................ 4 1.3 Objetivo y Alcance ....................................................................................... 5 1.4 Metodología ................................................................................................. 6 2. Evolución del PMTU Década 1960-1969 .................................... -

TSD: Chapter 36 Final Round 3 Area Designations for the 2010 1-Hour

Technical Support Document: Chapter 36 Final Round 3 Area Designations for the 2010 1-Hour SO2 Primary National Ambient Air Quality Standard for Puerto Rico 1. Summary Pursuant to section 107(d) of the Clean Air Act (CAA), the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (the EPA, we, or us) must designate areas as either “nonattainment,” “attainment,” or “unclassifiable” for the 2010 1-hour sulfur dioxide (SO2) primary national ambient air quality 1 standard (NAAQS) (2010 SO2 NAAQS). Our Notice of Availability (NOA) and our Technical Support Document2 (TSD) for our intended designations for the round of designations we are required to complete by December 31, 2017, provided background on the relevant CAA definitions and the history of the designations for this NAAQS. Chapter 1 of this TSD for the final designations explains the definitions we are applying in the final designations. The TSD for the intended Round 3 area designations also described Puerto Rico’s recommended designations, assessed the available relevant monitoring, modeling, and any other information, and provided our intended designations. This TSD for the final Round 3 area designations for Puerto Rico addresses any change in Puerto Rico’s recommended designations since we communicated our intended designations for areas in Puerto Rico. It also provides our assessment of additional relevant information that were submitted too close to the signature of the NOA to have been considered in our intended designations, or that have been submitted by Puerto Rico or other parties since the publication of the NOA. This TSD does not repeat information contained in the TSD for our intended designations except as needed to explain our assessment of the newer information and to make clear the final action we are taking and its basis, but that information is incorporated as part of our final designations. -

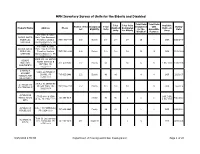

MFH Inventory Survey of Units for the Elderly and Disabled

MFH Inventory Survey of Units for the Elderly and Disabled Total Units Total Units Total Total Units Available Section of the Occupancy Total Designated with Survey Property Name Address Phone Assisted Designated Bedroom Act Eligibility Units for the Accessible Date Units for Elderly Sizes Disabled Features #10 Pablo R. Salas ACCION SOCIAL Hato Tejas Reverendo EGIDA LOS Florentino Santana (787) 786-0094 202 Elderly 100 100 100 16 0 1-BR 8/28/2008 CANTARES Building Bayamon, PR 00959-0000 #10 Pablo R. Salas ACCION SOCIAL Hato Tejas Reverendo EGIDA LOS Florentino Santana (787) 786-0094 202 Elderly 100 100 100 16 16 1-BR 11/10/2009 CANTARES Building Bayamon, PR 00959-0000 CARR. KM. 4.1 VICTOR ADOLFO ROJAS Street 18 B MARTINEZ 787- 879-4560 202 Elderly 55 55 6 6 0-BR, 1-BR 12/5/2006 ARECIBO, PR APARTMENTS 00612-0000 ALBERTO E. JOSE L QUINTON ST SANCHEZ COAMO, PR 787-825-2448 202 Elderly 48 48 4 4 1-BR 2/2/2007 HOUSING FOR 00769-0000 THE ELDERLY KM 4.5 65 INFANTRY ALTERGARTEN RD SAN JUAN, PR (787)769-2054 202 Elderly 100 100 100 10 0-BR 1/2/2009 LAS TERESAS II 00925-0000 ALTURAS DE ST RD KM 0.6 VEGA 1-BR, 2-BR, MONTE VERDE 787-883-6374 Family 60 60 0 0 5 4/21/2010 ALTA, PR 00692-0000 3-BR, 4-BR APTS ALTURAS DE Calle 1 J-17 PENUELAS, 787-836-1995 Family 88 88 0 0 0 3-BR 4/16/2010 PENUELAS II PR 00624-0000 Third St. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 (Rev. Aug. 2002) (Expires 1-31-2009) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. Name of Property historic name __Condado Vanderbilt Hotel_________________________________________________________ other names/site number Grand Hotel Condado Vanderbilt; The Condado Hotel; Hotel Condado; Condado Beach Hotel; Hyatt Puerto Rico Hotel______________ 2. Location street & number _1055 Ashford Avenue_______________________________________ not for publication city or town _______San Juan_________________________________________________ x vicinity state Puerto Rico_______ code _ PR__ county _San Juan___ code 127_ zip code 00907__ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property X meets does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant nationally X statewide locally. ( See continuation sheet for additional comments.) José Luis Vega Colón, PhD Signature of certifying official/Title Date State or Federal agency or Tribal government In my opinion, the property meets does not meet the National Register criteria. ( See -

Appraisal Report

Appraisal Report 12,771 SF/GCA - 10,502 SF/GRA Income Producing Multi-Unit Commercial-Office Property 415 Ing. Manuel V. Domenech Avenue, Reparto Parque Central Development Hato Rey Sur Ward, San Juan, Puerto Rico #20150226022 – Mandy’s BBQ Corporation Requested by Ms. Damaris Figueroa Rivera Appraisal Coordinator, Credit Risk Management Unidad Centralizada de Tasaciones / Oriental-Puerto Rico PO Box 364745 San Juan, Puerto Rico 00936-4745 As of April 21, 2015 Prepared on May 13, 2015 Suite A, 1001 Ponce de León Avenue, San Juan, Puerto Rico, 00907 Tel. 977-1940 / Fax 977-1903 / www.tasadorcomercial.com May 13, 2015 Ms. Damaris Figueroa Rivera Appraisal Coordinator, Credit Risk Management Unidad Centralizada de Tasaciones Oriental-Puerto Rico PO Box 364745 San Juan, Puerto Rico 00936-4745 RE:(13012) Dear Ms. Figueroa: In accordance with your request, we are submitting an appraisal report of a three (3) level multi- unit income producing commercial-office property that comprise 12,771 square feet of gross construction area and 10,502 square feet of gross rentable area, built on a 718.20 square meter site, located at 415 of Manuel V. Domenech Avenue in Reparto Parque Central Development of the Hato Rey Sur Ward in San Juan of Puerto Rico. The subject property enjoy a rear services entrance through Montilla Street. The property is leased/owner occupied yet mostly vacant. The purpose of this appraisal is to form an opinion of the “as is” market and liquidation values of the lease fee interest of the subject property, as defined in the report, subject to the assumptions, limiting conditions and certification also included in the report, as of April 21, 2015. -

2010 CENSUS - CENSUS TRACT REFERENCE MAP: San Juan Municipio, PR 65.976974W LEGEND SYMBOL DESCRIPTION SYMBOL LABEL STYLE Puerto Rico PUERTO RICO 72

18.568901N 18.568449N 66.143W 2010 CENSUS - CENSUS TRACT REFERENCE MAP: San Juan Municipio, PR 65.976974W LEGEND SYMBOL DESCRIPTION SYMBOL LABEL STYLE Puerto Rico PUERTO RICO 72 Municipio FLORIDA 054 Barrio or Barrio-Pueblo Palmas bar 58451 Subbarrio Mercado 53025 Comunidad or Guaynabo 32522 Zona Urbana 1 Census Tract 33.07 DESCRIPTION SYMBOL DESCRIPTION SYMBOL Pr- 52 Primary Road Water Body Cabo Rojo Ave Las Caobas Other Road Military Ft Allen 4WD Trail, Stairway, Alley, Walkway, or Ferry National or State Park, Calle Pelicano Cayo Mata Raiload Forest, or Recreation Area Pipeline or Inset Area Power Line A Ridge or Fence Outside Subject Area Property Line Nonvisible Boundary or Feature Not Elsewhere Classified Where Puerto Rico, municipio, and/or barrio or barrio-pueblo boundaries coincide, the map shows the boundary symbol for only the highest-ranking of these boundaries. 1 Label color correlates to the fill color. TOA BAJA 137 SAN JUAN 127 PUERTO RICO 72 LOÍZ A 087 1 A 03 OLIN CAR Océano Atlantico 9900 CAROLINA 031 Palo Seco bar 59268 Océano Atlántico LOÍZA 087 TOA BAJA 137 SAN JUAN 127 Ballajá 05180 9802 4 Ensenada de C ll Cll Lucila Silva Boca Vieja de l M or 9801.07 ro Mercado Bu Bahía de levar del Valle San San Juan 53025 Cristóbal 75843 Naval Base San Juan Cll Sol 9801.05 7 S Cll an A Cll de gu Cll sti la Luna n Sol San Juan Antiguo bar 76812 Ave Muñoz Rivera 5.06 Pr- 38 Puerta de Tierra 65249 Catedral 15355 137 Cll Marina Ave Juan JA Cll del Tren Ponce de León A BA Pso de la San Francisco 76042 O C Princesa l T l Cll Sur P Ave -

Cu Aderno De Investiga Ción En La Educa Ción

CUADERNO DE INVESTIGACIÓN EN LA EDUCACIÓN NÚMERO 30 • DICIEMBRE 2015 Índice Palabras preliminares SECCIÓN ESPECIAL Víctor Hernández-Rivera La Ley Federal de Educación Pública No Child Left Behind en los Estados NÚMERO 30 • 2015 DICIEMBRE • 30 NÚMERO ARTÍCULOS Unidos y Puerto Rico: Trayectoria e El baloncesto femenino escolar y impacto, 2002-2015 universitario al amparo del Título IX Ismael Ramírez-Soto María del R. Medina-Díaz Pedagogía Montessori, más allá del Building Teacher Skill by Learning método (en conversación sobre el about Racialized Experiences sentido del juicio y el educador) Described by Latin@ Middle and Eduardo J. Cuevas-González High School Youth Maria L. Gabriel Assessing a Graduate Schoool Science Recruitment Symposium Wilson González-Espada, Greetchen Díaz-Muñoz, Mónica Feliú-Mójer, Jacqueline Flores-Otero, Yaihara Fortis-Santiago, Giovanna Guerrero- Medina, Marcos López-Casillas, Daniel A. Colón-Ramos, & Emma Fernández-Repollet Análisis del contenido curricular en los documentos normativos del Programa de Ciencias para la escuela superior pública de Puerto Rico: 1993-2012 Melissa Dávila-Montañez Knowledge Production, Social Change and the Future of Research Universities: Trends and Challenges Eduardo Aponte-Hernández Arte: Bermarie Rodríguez Pagán CENTRO DE INVESTIGACIONES EDUCATIVAS NÚMERO 30 FACULTAD DE EDUCACIÓN DICIEMBRE 2015 UNIVERSIDAD DE PUERTO RICO ISSN 1540-0786 CUADERNO DE INVESTIGACIÓN EN LA EDUCACIÓN LA EN INVESTIGACIÓN DE CUADERNO RECINTO DE RÍO PIEDRAS ISSN 1540-0786 NÚMERO 30 DICIEMBRE 2015 IGACIO ST N E E V S Centro de Investigaciones Educativas N E I D E U Facultad de Educación D C A O T Universidad de Puerto Rico R I V T A N S E Recinto de Río Piedras C U P R CUADERNO DE INVESTIGACIÓN EN LA EDUCACIÓN Centro de Investigaciones Educativas, Facultad de Educación Universidad de Puerto Rico, Recinto de Río Piedras Uroyoán Walker Ramos, Ph.D. -

Senado De Puerto Rico Diario De Sesiones Procedimientos Y Debates De La Decimosexta Asamblea Legislativa Primera Sesion Ordinaria Año 2009 Vol

SENADO DE PUERTO RICO DIARIO DE SESIONES PROCEDIMIENTOS Y DEBATES DE LA DECIMOSEXTA ASAMBLEA LEGISLATIVA PRIMERA SESION ORDINARIA AÑO 2009 VOL. LVII San Juan, Puerto Rico Lunes, 16 de marzo de 2009 Núm. 20 A la una y diecisiete minutos de la tarde (1:17 p.m.) de este día, lunes, 16 de marzo de 2009, el Senado reanuda sus trabajos bajo la Presidencia de la señora Margarita Nolasco Santiago, Vicepresidenta. ASISTENCIA Senadores: Roberto A. Arango Vinent, Luis A. Berdiel Rivera, Eduardo Bhatia Gautier, José Ramón Díaz Hernández, Alejandro García Padilla, José E. González Velázquez, Angel Martínez Santiago, Migdalia Padilla Alvelo, Itzamar Peña Ramírez, Kimmey Raschke Martínez, Carmelo J. Ríos Santiago, Thomas Rivera Schatz, Luz M. Santiago González, Lawrence Seilhamer Rodríguez, Antonio Soto Díaz, Cirilo Tirado Rivera, Carlos Javier Torres Torres y Margarita Nolasco Santiago, Vicepresidenta. SRA. VICEPRESIDENTA: Habiendo quórum, se inician los trabajos del Senado de Puerto Rico, hoy lunes, 16 de marzo de 2009. (Se hace constar que después del Pase de Lista Inicial entraron a la Sala de Sesiones: las señoras Luz Z. Arce Ferrer, Norma E. Burgos Andújar; los señores José L. Dalmau Santiago, Antonio J. Fas Alzamora; la señora Sila María González Calderón; los señores Juan E. Hernández Mayoral, Héctor Martínez Maldonado, Luis D. Muñiz Cortés, Eder E. Ortiz Ortiz; las señoras Lornna Soto Villanueva y Evelyn Vázquez Nieves). INVOCACION El Reverendo Adolfo Santana y el Padre Efraín López Sánchez, miembros del Cuerpo de Capellanes del Senado de Puerto Rico, proceden con la Invocación. REVERENDO SANTANA: Oramos. Señor, queremos comenzar esta semana dándote muchas gracias por la vida que nos regalas. -

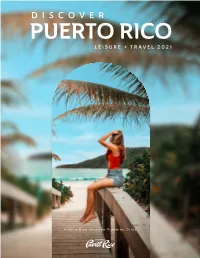

To See Our Puerto Rico Vacation Planning

DISCOVER PUERTO RICO LEISURE + TRAVEL 2021 Puerto Rico Vacation Planning Guide 1 IT’S TIME TO PLAN FOR PUERTO RICO! It’s time for deep breaths and even deeper dives. For simple pleasures, dramatic sunsets and numerous ways to surround yourself with nature. It’s time for warm welcomes and ice-cold piña coladas. As a U.S. territory, Puerto Rico offers the allure of an exotic locale with a rich, vibrant culture and unparalleled natural offerings, without needing a passport or currency exchange. Accessibility to the Island has never been easier, with direct flights from domestic locations like New York, Charlotte, Dallas, and Atlanta, to name a few. Lodging options range from luxurious beachfront resorts to magical historic inns, and everything in between. High standards of health and safety have been implemented throughout the Island, including local measures developed by the Puerto Rico Tourism Company (PRTC), alongside U.S. Travel Association (USTA) guidelines. Outdoor adventures will continue to be an attractive alternative for visitors looking to travel safely. Home to one of the world’s largest dry forests, the only tropical rainforest in the U.S. National Forest System, hundreds of underground caves, 18 golf courses and so much more, Puerto Rico delivers profound outdoor experiences, like kayaking the iridescent Bioluminescent Bay or zip lining through a canopy of emerald green to the sound of native coquí tree frogs. The culture is equally impressive, steeped in European architecture, eclectic flavors of Spanish, Taino and African origins and a rich history – and welcomes visitors with genuine, warm Island hospitality. Explore the authentic local cuisine, the beat of captivating music and dance, and the bustling nightlife, which blended together, create a unique energy you won’t find anywhere else. -

Gay Guide to Puerto Rico

APPENDIX D: GAY GUIDE TO PUERTO RICO Also please see our website www.PuertoRicoGayVacation.com Please email me any updates or additional information to [email protected] so we can keep the below info as up to date as possible. ! GAY LIFE: Puerto Rico is one of the most gay friendly of all Caribbean islands. Gay marriage and adoption is legal in Puerto Rico (see Ricky Martin). The two large Pride parades (one in Condado and one in Cabo Rojo) are well attended annually. Condado, Ocean Park, Santurce and Rio Piedras are the biggest “gayborhoods” though there are bars in Old San Juan as well. You should feel at ease with your partner on any beach, but particularly the Ocean Park beaches. The island of Vieques is also a gay haven. That being said, Puerto Rico is a very Catholic area and being gay is not always accepted. It may be best to use caution if you travel to any of the smaller cities/villages or leave the San Juan area. ! HEALTH CLINIC/HIV TESTING: Free instant HIV tests are available upon request at the walgreens clinic during normal hours (inside Walgreens). This takes about 30 minutes total. ! PRIDE: San Juan/Condado: Always in June. Typically news of the date is not available until late. The parade is always on Sunday about noon. Parties start usually the Thursday prior and continue through the weekend. The parade starts around noonish (island time) at Parque Indio and goes until Parque Escambron. After parties are at the beach of Atlantic Beach Hotel or other venues and clubs. -

Senado De Puerto Rico Diario De Sesiones Procedimientos Y Debates De La Decimosexta Asamblea Legislativa Tercera Sesion Extraordinaria Del Presidente Año 2011 Vol

SENADO DE PUERTO RICO DIARIO DE SESIONES PROCEDIMIENTOS Y DEBATES DE LA DECIMOSEXTA ASAMBLEA LEGISLATIVA TERCERA SESION EXTRAORDINARIA DEL PRESIDENTE AÑO 2011 VOL. LIX San Juan, Puerto Rico Jueves, 14 de julio de 2011 Núm. 1 A las once y cincuenta minutos de la mañana (11:50 a.m.) de este día, jueves, 14 de julio de 2011, el Senado inicia sus trabajos bajo la Presidencia del señor Thomas Rivera Schatz. ASISTENCIA Senadores: Roberto A. Arango Vinent, Luz Z. Arce Ferrer, Luis A. Berdiel Rivera, José R. Díaz Hernández, Antonio J. Fas Alzamora, Juan E. Hernández Mayoral, Roger J. Iglesias Suárez, Angel Martínez Santiago, Luis D. Muñiz Cortés, Margarita Nolasco Santiago, Migdalia Padilla Alvelo, Itzamar Peña Ramírez, Kimmey Raschke Martínez, Carmelo J. Ríos Santiago, Melinda K. Romero Donnelly, Antonio Soto Díaz, Lornna J. Soto Villanueva, Cirilo Tirado Rivera, Carlos J. Torres Torres y Thomas Rivera Schatz, Presidente. SR. PRESIDENTE: Habiendo el quórum requerido, iniciamos los trabajos de esta Tercera Sesión Extraordinaria convocada por este Presidente del Senado. (Se hace constar que después del Pase de Lista Inicial entraron a la Sala de Sesiones el señor Eduardo Bhatia Gautier; la señora Norma E. Burgos Andújar; los señores José Luis Dalmau Santiago, Alejandro García Padilla, Eder E. Ortiz Ortiz; la señora Luz M. Santiago González; y los señores Lawrence Seilhamer Rodríguez y Jorge I. Suárez Cáceres). SR. ARANGO VINENT: Señor Presidente. SR. PRESIDENTE: Señor Portavoz. SR. ARANGO VINENT: Señor Presidente, para ir a la Invocación. SR. PRESIDENTE: Adelante. INVOCACION La senadora Kimmey Raschke Martínez, procede con la Invocación. SRA. RASCHKE MARTINEZ: Dios les bendiga a todos en esta mañana. -

San Juan Harbor Mitigation Project, Draft FONSI and EA, 23 May 2014, Puerto Rico

SAN JUAN HARBOR SUBMERGED AQUATIC VEGETATION MITIGATION PROJECT, SAN JUAN, PUERTO RICO DRAFT ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT f.'Z"f.'' ~.:..:!.!.~ U.S. Army Corps of Engineers May 2014 Jacksonville District This page intentionally left blan EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Mitigation is required as a result of widening the Puerto Nuevo Channel in San Juan Harbor, which impacted an estimated 1.2 acres of sea grass (Halophila decipiens) and marine macro- algae. The mitigation originally proposed involved raising the bottom elevation of a portion of San Juan Harbor to support sea grass. This mitigation plan presents (among other concerns) engineering concerns over the confinement of the material used for raising the elevation. Extensive and costly structures would be needed to contain the material and prevent migration of material into the navigation channel. The new mitigation proposal would involve filling of approximately 4 acres (including side slopes) of certain dredged holes in the nearby Condado Lagoon with approximately 46,000 cubic yards of suitable material to a depth of -12 feet to -15 feet resulting in 1.2 acres at an elevation suitable for sea grass. The fill material would come from the recently shoaled areas of the La Esperanza Ecosystem Restoration project located along the western shore of San Juan Bay. An alternative borrow source would be the San Antonio channel in San Juan Harbor. In La Esperanza, one borrow source would be the north-facing opening into San Juan Bay. The east-facing opening could also provide some material if needed. See enclosed maps and drawings for additional details. Both of these areas have experienced substantial shoaling since the completion of the La Esperanza Ecosystem Restoration Project on May 20, 2005.