Students on the Right Way

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Populist Backlash Against Europe : Why Only Alternative Economic and Social Policies Can Stop the Rise of Populism in Europe

This is a repository copy of The populist backlash against Europe : why only alternative economic and social policies can stop the rise of populism in Europe. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/142119/ Version: Accepted Version Book Section: Bugaric, B. (2020) The populist backlash against Europe : why only alternative economic and social policies can stop the rise of populism in Europe. In: Bignami, F., (ed.) EU Law in Populist Times : Crises and Prospects. Cambridge University Press , pp. 477-504. ISBN 9781108485081 https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108755641 © 2020 Francesca Bignami. This is an author-produced version of a chapter subsequently published in EU Law in Populist Times. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. See: https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108755641. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ The Populist Backlash Against Europe: Why Only Alternative Economic and Social Policies Can Stop the Rise of Populism in Europe Bojan Bugarič1 I. -

Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe

This page intentionally left blank Populist radical right parties in Europe As Europe enters a significant phase of re-integration of East and West, it faces an increasing problem with the rise of far-right political par- ties. Cas Mudde offers the first comprehensive and truly pan-European study of populist radical right parties in Europe. He focuses on the par- ties themselves, discussing them both as dependent and independent variables. Based upon a wealth of primary and secondary literature, this book offers critical and original insights into three major aspects of European populist radical right parties: concepts and classifications; themes and issues; and explanations for electoral failures and successes. It concludes with a discussion of the impact of radical right parties on European democracies, and vice versa, and offers suggestions for future research. cas mudde is Senior Lecturer in the Department of Political Science at the University of Antwerp. He is the author of The Ideology of the Extreme Right (2000) and the editor of Racist Extremism in Central and Eastern Europe (2005). Populist radical right parties in Europe Cas Mudde University of Antwerp CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 8RU, UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521850810 © Cas Mudde 2007 This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provision of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. -

1St Meeting of the Think Tank on Youth Participation 3-4 April 2018 Tallinn, Estonia

1st meeting of the Think Tank on Youth Participation 3-4 April 2018 Tallinn, Estonia INTRODUCING THE THINKERS Facilitator: Alex Farrow (United Kingdom) Alex supports civil society in the UK and around the world, attempting to improve the lives of communities through knowledge, training and expression. Building on his global work with activists and youth movements internationally, Alex is currently working at the National Council of Voluntary Organisations in England, supporting voluntary organisations to strengthen their strategy and evaluate their impact. Alex's area of interest are youth participation, policy and practice. He worked for the National Youth Agency and the British Youth Council, as well as freelancing extensively with organisations in the youth development sector. He has undertaken numerous research projects on youth participation, including with Restless Development, Commonwealth Secretariat, SALTO, and UNICEF. At Youth Policy Labs, Alex led on consultancy projects, supporting national governments and UN agencies to design, implement and evaluate national youth policies, through research, training and events. Alex is a campaigner - mostly on climate change, child rights and young people - and is active in UK politics. He is currently a trustee of Girlguiding UK and a member of the CIVICUS Youth Action Team. Airi-Alina Allaste (Estonia) I am professor of sociology specialising in youth studies. For the past fifteen years I have been investigating young people’s participation including political participation, belonging to subcultures, impact of mobility and informal education to participation etc. The focus of the studies has been on the meanings that young people attribute to their participation, which has been analysed in the wider social context. -

Association of Accredited Lobbyists to the European Parliament

ASSOCIATION OF ACCREDITED LOBBYISTS TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT OVERVIEW OF EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT FORUMS AALEP Secretariat Date: October 2007 Avenue Milcamps 19 B-1030 Brussels Tel: 32 2 735 93 39 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.lobby-network.eu TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction………………………………………………………………..3 Executive Summary……………………………………………………….4-7 1. European Energy Forum (EEF)………………………………………..8-16 2. European Internet Forum (EIF)………………………………………..17-27 3. European Parliament Ceramics Forum (EPCF………………………...28-29 4. European Parliamentary Financial Services Forum (EPFSF)…………30-36 5. European Parliament Life Sciences Circle (ELSC)……………………37 6. Forum for Automobile and Society (FAS)…………………………….38-43 7. Forum for the Future of Nuclear Energy (FFNE)……………………..44 8. Forum in the European Parliament for Construction (FOCOPE)……..45-46 9. Pharmaceutical Forum…………………………………………………48-60 10.The Kangaroo Group…………………………………………………..61-70 11.Transatlantic Policy Network (TPN)…………………………………..71-79 Conclusions………………………………………………………………..80 Index of Listed Companies………………………………………………..81-90 Index of Listed MEPs……………………………………………………..91-96 Most Active MEPs participating in Business Forums…………………….97 2 INTRODUCTION Businessmen long for certainty. They long to know what the decision-makers are thinking, so they can plan ahead. They yearn to be in the loop, to have the drop on things. It is the genius of the lobbyists and the consultants to understand this need, and to satisfy it in the most imaginative way. Business forums are vehicles for forging links and maintain a dialogue with business, industrial and trade organisations. They allow the discussions of general and pre-legislative issues in a different context from lobbying contacts about specific matters. They provide an opportunity to get Members of the European Parliament and other decision-makers from the European institutions together with various business sectors. -

Jahresrückblick 2012 Deutsch-Luxemburgisches

JAHRESRÜCKBLICK 2012 DEUTSCH-LUXEMBURGISCHES Frank Piplat, Leiter des Informationsbüros des Europäischen Parlaments in Deutschland, lädt Sie herzlich ein zu: BÜRGERFORUM NG U O Y & AM S E Wettbewerb AGENC Euroscola 2012 MISCH M In Vielfalt geeint United in diversity DONNERSTAG, 26. A IT ! Unie dans la diversité PRIL 2012, 19.00 UHR Worum geht es beim Wettbewerb? Setzt das Motto der Europäischen Union „In Vielfalt geeint“ kreativ um – ob als Blog, Hörspiel, Video Wer kann mitmachen? Alle Schülerinnen und Schüler der oder Zeitung. BÜRGERFORUM im Alter von 16 bis 18 Jahre. - Rede und Antwort stehen Mitmachen könnt Ihr als Schul gruppe mit bis zu 24 Schüler- am Donnerstag, 18. Oktober 2012 | 19.00 Uhr die Europaabgeordneten : innen und Schülern. im Brandenburgsaal in der Staatskanzlei des Landes Brandenburg Heinrich-Mann-Allee 107 | 14473 Potsdam Was gibt es zu gewinnen? Charles GOERENS (DP) Als Gewinner des Wett- In Europa diskutiert man über die Zukunftsfragen der Europäischen Union. Diskutieren Sie mit! Christa KLAß (CDU) bewerbs nehmt Ihr als Vertreter am deutsche Begrüßung: Henning Heidemanns Norbert NEUSER (SPD) Programm Euroscola im Staatssekretär im Ministerium für Wirtschaft und Europaangelegenheiten des Landes Brandenburg Claude TURMES Europäischen Parlament Frank Piplat (Déi Gréng) in Straßburg teil und Leiter des Informationsbüros des Europäischen Parlaments in Deutschland CSAK A SZÉL werdet bei Eurer (JUST THE WIND) Podium: Dr. Christian Ehler BENCE FLIEGAUF Fahrt nach Straß- Mitglied des Europäischen Parlaments (CDU) IO SONO LI burg finanziell (SHUN LI AND THE POET) LUX Norbert Glante unterstützt. Mitglied des Europäischen Parlaments (SPD) ANDREA SEGRE QUO VADIS, Gestaltung: www.typoly.de Gestaltung: Helmut Scholz TABU und mischt mit Mitglied des Europäischen Parlaments (DIE LINKE) MIGUEL GOMES Elisabeth Schroedter FILM EUROPA ? Mitglied des Europäischen Parlaments (BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN) MONTAG UND DIENSTAG, 12. -

ESS9 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS9 - 2018 ed. 3.0 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Bulgaria 7 Croatia 8 Cyprus 10 Czechia 12 Denmark 14 Estonia 15 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Italy 26 Latvia 28 Lithuania 31 Montenegro 34 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 44 Serbia 47 Slovakia 52 Slovenia 53 Spain 54 Sweden 57 Switzerland 58 United Kingdom 61 Version Notes, ESS9 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS9 edition 3.0 (published 10.12.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Denmark, Iceland. ESS9 edition 2.0 (published 15.06.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2017 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ) - Social Democratic Party of Austria - 26.9 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) - Austrian People's Party - 31.5 % election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) - Freedom Party of Austria - 26.0 % 4. Liste Peter Pilz (PILZ) - PILZ - 4.4 % 5. Die Grünen – Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne) - The Greens – The Green Alternative - 3.8 % 6. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ) - Communist Party of Austria - 0.8 % 7. NEOS – Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum (NEOS) - NEOS – The New Austria and Liberal Forum - 5.3 % 8. G!LT - Verein zur Förderung der Offenen Demokratie (GILT) - My Vote Counts! - 1.0 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

The Similarities and the Differences in the Functioning of the European Right Wing: an Attempt to Integrate the European Conservatives and Christian Democrats

Journal of Social Welfare and Human Rights, Vol. 1 No. 2, December 2013 1 The Similarities and the Differences in the Functioning of the European Right Wing: An Attempt to Integrate the European Conservatives and Christian Democrats Dr. Kire Sarlamanov1 Dr. Aleksandar Jovanoski2 Abstract The text reviews the attempt of the European Conservative and Christian Democratic Parties to construct a common platform within which they could more effectively defend and develop the interests of the political right wing in the European Parliament. The text follows the chronological line of development of events, emphasizing the doctrinal and the national differences as a reason for the relative failure in the process of unification of the European right wing. The subcontext of the argumentation protrudes the ideological, the national as well as the religious-doctrinal interests of some of the more important Christian Democratic, that is, conservative parties in Europe, which emerged as an obstacle of the unification. One of the more important problems that enabled the quality and complete unification of the European conservatives and Christian Democrats is the attitude in regard to the formation of EU as a federation of countries. The weight down of the British conservatives on the side of the national sovereignty and integrity against the Pan-European idea for united European countries formed on federal basis, is considered as the most important impact on the unification of the parties from the right ideological spectrum on European land. Key words: Conservative Party, Christian Democratic Party, CDU European Union, European People’s Party. 1. Introduction On European land, the trend of connection of political parties on the basis of ideology has been notable for a long time. -

Parliaments and Legislatures Series Samuel C. Patterson

PARLIAMENTS AND LEGISLATURES SERIES SAMUEL C. PATTERSON GENERAL ADVISORY EDITOR Party Discipline and Parliamentary Government EDITED BY SHAUN BOWLER, DAVID M. FARRELL, AND RICHARD S. KATZ OHI O STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS COLUMBUS Copyright © 1999 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Party discipline and parliamentary government / edited by Shaun Bowler, David M. Farrell, and Richard S. Katz. p. cm. — (Parliaments and legislatures series) Based on papers presented at a workshop which was part of the European Consortium for Political Research's joint sessions in France in 1995. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8142-0796-0 (cl: alk. paper). — ISBN 0-8142-5000-9 (pa : alk. paper) 1. Party discipline—Europe, Western. 2. Political parties—Europe, Western. 3. Legislative bodies—Europe, Western. I. Bowler, Shaun, 1958- . II. Farrell, David M., 1960- . III. Katz, Richard S. IV. European Consortium for Political Research. V. Series. JN94.A979P376 1998 328.3/75/ 094—dc21 98-11722 CIP Text design by Nighthawk Design. Type set in Times New Roman by Graphic Composition, Inc. Printed by Bookcrafters, Inc.. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48-1992. 98765432 1 Contents Foreword vii Preface ix Part I: Theories and Definitions 1 Party Cohesion, Party Discipline, and Parliaments 3 Shaun Bowler, David M. Farrell, and Richard S. Katz 2 How Political Parties Emerged from the Primeval Slime: Party Cohesion, Party Discipline, and the Formation of Governments 23 Michael Laver and Kenneth A. -

European Parliament 2014-2019

European Parliament 2014-2019 Committee on Fisheries PECH_PV(2015)0922_1 MINUTES Meeting of 22 September 2015, 15:00-18:30, and 23 September 2015, 9:00-12:30-15:00-18:30 and 15:00-18:30-18:30 BRUSSELS The meeting opened at 15:00 on Tuesday, 22 September 2015, with Alain Cadec (Chair) presiding. 1. Adoption of agenda PECH_OJ (2015)0922_1 The agenda was adopted with following change: the point 13 was taken instead of point 8 , and vice-versa. 2. Chair's announcements None. 3. Approval of minutes of the meeting of: 3 September 2015 PE 567.469v01-00 The minutes were approved. 4. Public hearing on the Multispecies Management Plans for Fisheries Speakers: Alain Cadec, Ireneusz Wojcik (National Marine Fisheries Research Institute, Poland), Olivier Leprêtre (President of the regional fisheries committee of Boulogne-sur-Mer, France), Marek Józef Gróbarczyk, Ulrike Rodust, Linnéa Engström, Raymond Finch, Peter van Dalen, Simon Collins (Head of Shetland Fisherman's Association, Scotland, UK), Raul Prellezo (Principal Researcher, AZTI, Basque Country, Spain), Jarosław Wałęsa, Ian Hudghton, David Coburn, Ian Duncan, Izaskun Bilbao Barandica, Gabriel Mato, Richard Corbett, Andrew Clayton (Project Director, The Pew Charitable Trusts, UK), Pim Visser (Chief Executive of VisNed, the Netherlands), Joost Paardekooper (EC) PV\1073498EN.doc PE567.777v01-00 EN United in diversity EN 5. Coordinators’ meeting IN CAMERA. 6. Provisions for fishing in the GFCM (General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean) Agreement area PECH/8/03213 ***II 2014/0213(COD) 08806/1/2015 – C8-0260/2015 T8-0005/2015 Rapporteur: Gabriel Mato (PPE) PR – PE565.194v01-00 Responsible: PECH Consideration of draft recommendation (consent) Decision on deadline for tabling amendments Speakers: Alain Cadec, Gabriel Mato, Clara Eugenia Aguilera García, Ruža Tomašić, Izaskun Bilbao Barandica, Ricardo Serrão Santos, Remo Sernagiotto, Fabrizio Donatella (EC) Deadline for tabling amendments: 24/09/2015 at 12:00 7. -

EU-27 Watch No 8

EU-27 WATCH No. 8 ISSN 1610-6458 Issued in March 2009 Edited by the Institute for European Politics (IEP), Berlin in collaboration with the Austrian Institute of International Affairs, Vienna Institute for International Relations, Zagreb Bulgarian European Community Studies Association, Institute for World Economics of the Hungarian Sofia Academy of Sciences, Budapest Center for European Studies / Middle East Technical Institute for Strategic and International Studies, University, Ankara Lisbon Centre européen de Sciences Po, Paris Institute of International and European Affairs, Centre d’étude de la vie politique, Université libre de Dublin Bruxelles Institute of International Relations, Prague Centre d’Etudes et de Recherches Européennes Institute of International Relations and Political Robert Schuman, Luxembourg Science, Vilnius University Centre of International Relations, Ljubljana Istituto Affari Internazionali, Rome Cyprus Institute for Mediterranean, European and Latvian Institute of International Affairs, International Studies, Nicosia Riga Danish Institute for International Studies, Mediterranean Academy of Diplomatic Studies, Copenhagen University of Malta Elcano Royal Institute and UNED University, Madrid Netherlands Institute of International Relations European Institute of Romania, Bucharest ‘Clingendael’, The Hague Federal Trust for Education and Research, London Slovak Foreign Policy Association, Bratislava Finnish Institute of International Affairs, Helsinki Stockholm International Peace Research Institute Foundation -

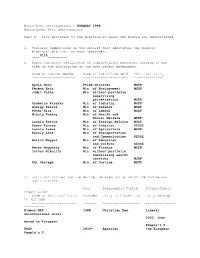

HUNGARY 1998 Macro-Level Data Questionnaire Part I: Data Pertinent

Macro-Data Questionnaire - HUNGARY 1998 Macro-Level Data Questionnaire Part I: Data Pertinent to the Election at which the Module was Administered 1. Variable number/name in the dataset that identifies the primary electoral district for each respondent. ____V114__________ 2. Names and party affiliation of cabinet-level ministers serving at the time of the dissolution of the most recent government. Name of Cabinet Member Name of the Office Held Political Party ---------------------- ----------------------- --------------- Gyula Horn Prime Minister MSZP Ferenc Baja Min. of Environment MSZP Judit Csiha Min. without portfolio supervising privatization MSZP Szabolcs Fazakas Min. of Industry MSZP Gyorgy Keleti Min. of Defence MSZP Peter Kiss Min. of Labour MSZP Mihaly Kokeny Min. of Health and Social Welfare MSZP Laszlo Kovacs Min. of Foreign Affairs MSZP Gabor Kuncze Min. of Interior SZDSZ Laszlo Lakos Min. of Agriculture MSZP Karoly Lotz Min. of Transportation and Communication SZDSZ Balint Magyar Min. of Education and Culture SZDSZ Peter Megyessy Min. of Finance MSZP Istvan Nikolits Min. without portfolio supervising secret services MSZP Pal Vastagh Min. of Justice MSZP 3. Political Parties (active during the election at which the module was administered). Year Ideological Family International Organization Name of Political Party Founded Party is Closest to Party Belongs to (if any) ----------------------- ------- ------------------- ---------------- ---------- Fidesz-MPP 1988 Christian Dem. Liberal International until 2000, then moved to European People's P. FKGP 1930* Agrarian the European People's P. suspended the FKGP's membership in 1992 KDNP 1988 Christian Dem. The European People's P. suspended the KDNP's membership in 1997 MDF 1988 Christian Dem. European People's P. -

Finnish and Swedish Policies on the EU and NATO As Security Organisations

POST-NEUTRAL OR PRE-ALLIED? Finnish and Swedish Policies on the EU and NATO as Security Organisations Tapani Vaahtoranta Faculty Member Geneva Center for Security Policy email: [email protected] Tuomas Forsberg Director Finnish Institute of International Affairs email: [email protected] Working Papers 29 (2000) Ulkopoliittinen instituutti (UPI) The Finnish Institute of International Affairs Tapani Vaahtoranta - Tuomas Forsberg POST-NEUTRAL OR PRE-ALLIED? Finnish and Swedish Policies on the EU and NATO as Security Organisations This report was made possible by NATO Research Fellowships Programme 1998/2000. We would also like to thank Niklas Forsström for his contribution in preparing the report as well as Jan Hyllander and Hanna Ojanen for comments on earlier drafts. We are also grateful to Fredrik Vahlquist of the Swedish Embassy in Helsinki and Pauli Järvenpää of the Finnish Representation to NATO who were helpful in organizing our fact finding trips to Stockholm in November 1999 and to Brussels in April 2000. Finally, Kirsi Reyes, Timo Brock and Mikko Metsämäki helped to finalise this Working Paper. 2 Contents Finland and Sweden: Twins, Sisters, or Cousins? 3 The Past: Neutrals or “Neutrals”? 7 Deeds: The Line Drawn 14 Words: The Line Explained 19 The Debate: The Line Challenged 27 Public Opinion: The Line Supported 34 The Future Line 37 3 Finland and Sweden: Twins, Sisters, or Cousins? At the beginning of the 21st century – a decade after the end of the Cold War – two major developments characterise the transformation of the European security landscape. The first development is the NATO enlargement and its evolving strategic concept that was applied in the Kosovo conflict.