Places of Live Music: Eventful Geographies of the Roundhouse and the Troubadour

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Joys of Advertisements Istorians and Others Who Study Suschitzky’S Bookshop Libris at 38 Boundary in 1968

VOLUME 15 NO.3 MARCH 2015 journal The Association of Jewish Refugees The joys of advertisements istorians and others who study Suschitzky’s bookshop Libris at 38 Boundary in 1968. Its second branch, just off Finchley patterns of consumption have long Road, a mecca for scholars and connoisseurs Road facing the side of what is now Waitrose been aware of the importance of of German books. Well known in its time was John Barnes, opened in 1956 and survived Hadvertisements as rich sources of material; the Blue Danube Club at 153 Finchley Road, into the 21st century. Gideon Reuveni of the Centre for German- where Peter Herz directed Continental-style Refugee businesses in this part of London Jewish Studies at the University of Sussex, for reviews until he returned to his native Vienna catered to their clients’ needs across the example, has published fascinating work on in 1953; the Blue Danube Club was itself board of everyday life. In the sphere of office the Jews of Germany as consumers in the pre- an offshoot of another Kleinkunstbühne, the equipment, A. Breuer of 43 Buckland Crescent Hitler era. As I have myself learnt a great deal small-stage cabaret theatre Das Laterndl (The specialised in the repair and maintenance of about the community of Jewish refugees from Lantern), which had been set up at 69 Eton typewriters, while Ernst Rosenthal of 92 Eton Nazism in Britain from the ads in the back Avenue by the wartime Austrian Centre. Place, Eton College Road, offered ‘photocopies issues of AJR Information, I was intrigued by The distinctively Continental atmosphere in the middle of Hampstead’. -

Phil Cohen, Reading Room Only: Memoir of a Radical Bibliophile And

Phil Cohen, Reading Room Only: Memoir of a Radical Bibliophile, hardback, 274 pages, Nottingham: Five Leaves, 2013. ISBN: 978-1907869785; £14.99. and Sophie Parkin, The Colony Room Club: A History of Bohemian Soho, 1948-2006, hardback, 265 pages, London: Palmtree Publishers, 2012. ISBN: 978-0957435407; £35. Reviewed by James Heartfield (Freelance, UK) The Literary London Journal, Volume 12 Number 1–2 (Spring/Autumn 2015) Bloomsbury and Soho in the nineteenth century were places where political refugees lived, though the Germans preferred Bloomsbury, just to the north, on the grounds that the Parisians of Soho were all drunks and womanisers. Phil Cohen is a long-standing activist and now academic, who has written his memoir of radical Bloomsbury, while writer and club manager Sophie Parkin’s history of drinking clubs takes Soho as its epicentre, and in particular the Colony Club on Dean Street. Phil Cohen was sent to St Paul’s School and later Oxford, but his attention was taken up by the London of Somerstown and Bloomsbury. As a youth worker, he wandered through the radical 1960s, being involved in various movements of the Fluxus and Situationist art scene that he met in bookshops like Better Books, India, and later Gay’s the Word, and working for a while as an assistant to the surrealist John Latham. He participated in the radical psychoanalytic movement led by R. D. Laing, paying for his treatment with more youth work, and then took part in the Dialectic of Liberation conference with Black Power’s Stokely Carmichael, New Leftist Herbert Marcuse and Beat poet Allen Ginsberg at the Roundhouse in 1967. -

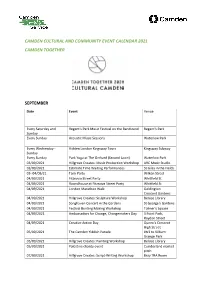

Camden Cultural and Community Event Calendar 2021 Camden Together

CAMDEN CULTURAL AND COMMUNITY EVENT CALENDAR 2021 CAMDEN TOGETHER SEPTEMBER Date Event Venue Every Saturday and Regent's Park Music Festival on the Bandstand Regent's Park Sunday Every Sunday Acoustic Music Sessions Waterlow Park Every Wednesday - Hidden London Kingsway Tours Kingsway Subway Sunday Every Sunday Park Yoga at The Orchard (Second Lawn) Waterlow Park 03/09/2021 Hillgrove Creates: Music Production Workshop ARC Music Studio 03/09/2021 Estimate Time Waiting Performances St Giles in the Fields 03- 04/09/21 Tank Party Wilken Street 04/09/2021 Fitzrovia Street Party Whitfield St 04/09/2021 Roundhouse at Fitzroiva Street Party Whitfield St 04/09/2021 London Marathon Walk Goldington Crescent Gardens 04/09/2021 Hillgrove Creates: Sculpture Workshop Belsize Library 04/09/2021 Songhaven Concert in the Gardens St George's Gardens 04/09/2021 Festival Bunting Making Workshop Tolmer's Square 04/09/2021 Ambassadors for Change, Changemakers Day 3 Point Park, Raydon Street 04/09/2021 Creative Action Day Queen's Crescent High Street 05/09/2021 The Camden Yiddish Parade JW3 to Kilburn Grange Park 05/09/2021 Hillgrove Creates: Painting Workshop Belsize Library 05/09/2021 Palestine charity event Cumberland market pitch 07/09/2021 Hillgrove Creates: Script-Writing Workshop Bray TRA Room 07/09/2021 Hillgrove Creates: Music Production Workshop ARC Music Studio 08/09/2021 Hillgrove Creates: Music Production Workshop ARC Music Studio 09/09/2021 Hillgrove Creates: Theatre Performance Belsize Library Workshop 09/09/2021 Hillgrove Creates: Music Production -

Roundhouse Access Guide 1. Introduction 2. Contact Details 3

Roundhouse Access Guide 1. Introduction 2. Contact Details 3. Venue Description 4. Bookable Access Facilities 5. How to apply 6. Travel Guide 7.1 By Tube 7.2 By Overground 7.3 By Bus 7.4 By Coach 7.5 By CarArrival Guide 7. Toilets 8. Customers with Medical Requirements 9. Access to Performance 9.1 Facilities for Deaf and Hard of Hearing Patrons 9.2 Facilities for Blind or Vision-Impaired Visitors 9.3 Venue Accessibility for Wheelchair Users 9.4 Relaxed Performances at the Roundhouse 10. Assistance Dogs 11. Strobe Lighting ///////////////////////////////////////////////// 1. Introduction We’re committed to making all aspects of your visit to the Roundhouse enjoyable, universally welcoming and physically accessible and are proud to have been awarded a Gold Standard Award from Attitude is Everything, recognising our on-going commitment to provide the best possible experience for deaf and disabled visitors ///////////////////////////// 2. Contact Details To discuss any access-related enquiries, please don’t hesitate to contact us: [email protected] www.roundhouse.org.uk 0300 6789 222, Option 3 (Roundhouse Access Enquiries and Accessible Ticket Purchasing) Roundhouse, Chalk Farm Road, London, NW1 8EH We will endeavor to respond to your enquiries as soon as possible. Generally speaking, this will be within 24 hours, though postal responses and requests received outside workings hours (weekends and holidays) may take a little longer. //////////////////////////////////// 3. Venue Description The Roundhouse has step free (lift) access to Accessible Toilets, Bars and Performance Spaces on all levels as well as level access to the Box Office, MADE Bar and Kitchen and Paul Hamlyn Roundhouse Studios on Level 0. -

Restaurants British French Italian Greek

11 6 RESTAURANTS BRITISH Freud 1. ODETTE’S Museum 130 Regents Park Road NW1 8XL Tel. 020 7586 8569 FRENCH TOP LOCAL ATTRACTIONS 2. BRADLEYS 25 Winchester Road 9 NW3 3NR Tel. 020 7722 3457 ENTERTAINMENT & SPORTS 3. L’ABSINTHE VENUES Hampstead Chalk 40 Chalcot Road Theatre Farm Roundhouse NW1 8LS Tel. 020 7843 4848 Regent’s Park Open Air Theatre Swiss ITALIAN Roundhouse 19 Camden CoƩage 18 4. VILLA BIANCA Lord's Cricket Ground 2 Market Jason’sJa Trip 1 Perrin’s Court, Hampstead //London NW3 1QS Tel. 020 7435 3131 Hampstead Theatre 5. J PIZZERIA AND CUCINA 17 WWaterbus 10 7 148 Regents Park Road PARKS & OUTDOOR ACTIVITIES 13 NW1 8XN Tel. 020 7586 9100 5 6. ARTIGIANO Regent's Park 12A Belsize Terrace Primrose Hill South 14 1 NW3 4AX Tel. 020 7794 4288 Primrose 16 15 Camden GREEK ZSL London Zoo Hampstead Hill Lock Camden 3 Town 7. LEMONIA Jason’s Trip - Canal Tours 89 Regents Park Road London Waterbus Company - Boat Trips NW1 8UY Tel. 020 7586 7454 CHINESE 8. ROYAL CHINA CLUB SHOPS & MARKETS 40-42 Baker Street Camden Market W1U 7AJ Tel. 020 7486 3898 9. CHINA GARDEN Camden Lock 5-6 New College Parade NW3 5EP Tel. 020 7722 9552 MUSEUMS & LANDMARKS The Jewish MALAYSIAN Museum Madame Tussauds 10. SINGAPORE GARDEN ZSL London 83 Fairfax Road Freud Museum Zoo NW6 4DY Tel. 020 7328 5314 The Jewish Museum Mornington INDIAN Crescent 11. HAZARA Abbey Road Studios & Crossing St. John’s 44 Belsize Lane Wood NW3 5AR Tel. 020 7433 1147 STEAKHOUSE FOR MORE ATTRACTIONS, 12. -

"A Band on Every Corner": Using Historical GIS to Describe Changes in the Sydney and Melbourne Live Music Scenes

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Social Sciences - Papers Faculty of Arts, Social Sciences & Humanities 2014 "A Band on Every Corner": Using Historical GIS to Describe Changes in the Sydney and Melbourne Live Music Scenes Sarah Taylor Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology Colin Arrowsmith Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology, [email protected] Nicole T. Cook University of Wollongong, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/sspapers Part of the Education Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Taylor, Sarah; Arrowsmith, Colin; and Cook, Nicole T., ""A Band on Every Corner": Using Historical GIS to Describe Changes in the Sydney and Melbourne Live Music Scenes" (2014). Faculty of Social Sciences - Papers. 3071. https://ro.uow.edu.au/sspapers/3071 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] "A Band on Every Corner": Using Historical GIS to Describe Changes in the Sydney and Melbourne Live Music Scenes Abstract This paper demonstrates the use of historical Geographic Information Systems (historical GIS) to investigate live music in Sydney and Melbourne. It describes the creation of a tailored historical geodatabase built from samples of gig listings (comprising dates, locations, and performer names), and how this historical geodatabase offers insight into the changing dynamics of performers and venue locations. The major findings from the analyses using the developed historical geodatabase are that neither city showed a decline in live music performance or performer numbers, but Melbourne increased at a greater rate than Sydney. -

Mpowerissue4resizedc.Pdf

- Action methods - Film production with young people - Interactive workshops -Issue based Theatre in Edu- cation Recent clients include Nor- wich Playhouse UK, Anti-Bul- lying Alliance (ABA), Govern- ment Departments, (eg DFES, DOE)British Council, Regional and Borough Councils, Kyoto University, the Dawn Center Japan, University of London, Whitechapel Hospital, The Norwegian Institute of Dram- atherapy, Belmarsh prison, Exeter University, schools & Actionwork We don’t just talk we do youth centres across the UK. Actionwork comes to you. We Theatre - Film - Education travel the length and breadth of the country and to many destinations abroad. Please Action = The causation of just sit around chatting about contact us for further details. change by the exertion of a topic, actually get in to it. power Live your topic, document it, We want to hear from you. draw inspiration from it, feel Work = Accomplishment the vibes of it, tune in to it. Actionwork, PO Box 433, through action activities Take your thoughts and ideas WSM, BS24 0WY, England UK on to a new level. Find new Actionwork makes films and angles of experience and ex- Tel: 01934 815163 produces theatre. Also check pression. Feel the force! Website: out our creative workshops & other educational sessions. Make a film, learn how to use www.actionwork.com a camera, direct actors or act Actionwork specialises in yourself. Create music and tackling bullying, racism, and drama. Play games! Produce sexism through the power of a play, make masks, design a multimedia and action. Arts set or manage a stage. Have fusion, ritual, celebration, fun and create action. -

Ricky Martin

B63C:B7;/B35C723B=5/G:=<2=< 3 4@3 @719G;/@B7< :/B7<AC>3@AB/@5/G2/2 7<A72323>CBG;/G=@@716/@20/@<3A;=23@<4/;7:G 83@3;G8=A3>6B636C;/<:3/5C3:=D30=F A13<3B@/<<GA6/195CBB3@A:CB 3/AB3@>/@B73A EEE=Cb;/51=C9 7AAC3474BGBE=" =CbT`]\b PAGE 20 PAGE 38 RICKY MARTIN FOOD EDITORIAL// Coq D’Argent reviewed ADVERTISING PAGE 41 MOVING ON Editor Healing a broken heart David Hudson [email protected] PAGE 43 +44 (0)20 7258 1943 OUT THERE Design Concept Upcoming scene Boutique Marketing highlights for April, www.boutiquemarketing.co.uk plus coverage of Graphic Designer Trannyshack and the Ryan Beal launch of Pulse Sub Editor Chance Delgado PAGE 63 Contributors OUTREACH Richard Bevan, Stuart Why LGBT charity PACE Brumfi tt, Adrian Foster, needs your help, and Daniel Fry, Simon Gage, community listings Anthony Gordon, Nick Levine, Paul Murphy, John PAGE 66 O‘Ceallaigh, George Prior, Lily OUTNEWS Rogers, Justin Swift, Richard All the gay news from Tonks, Michael Turnbull, Josh CONTENTS home and abroad Winning Photographer Chris Jepson PAGE 04 Publishers LETTERS Sarah Garrett//Linda Riley Send your ISDN: 1473-6039 correspondence to Head of Advertising editorial@outmag. Rob Harkavy co.uk PHOTO CHRIS © JEPSON [email protected] + 44 (0)20-7258 1777 PAGE 06 Head of Business MY LONDON Development HUDSON’S LETTER DJ Ariel gives us his Lyndsey Porter capital highlights… PAGE 48 [email protected] Gay parenting stories have Increasingly, adoption and SUPERMARTXÉ AT PULSE + 44 (0)20-7258 1777 been featuring more in fostering agencies across PAGE 08 Advertising Manager the news recently. -

Roundhouse Annual Review 2012/13

TICKETS 0844 482 8008 ROUNDHOUSE WWW.ROUNDHOUSE.ORG.UK ANNUAL REVIEW 2012/13 ROUNDHOUSE CHALK FARM ROAD LONDON NW1 8EH ENERGY, ENTHUSIASM & INVENTIVENESS Christopher Satterthwaite Chairman, the Roundhouse Trust Nothing has inspired me more during my time at the Ron Arad, Anthony Gormley, Alan Bennett and Roundhouse than our work with young people and Sebastian Coe, among others. the way that work runs through everything we do. Since taking my seat around the Board table at the end From our very own Street Circus troupe performing at of 2010, I’ve been continually impressed by the energy, CircusFest, to the Broadcast Crew live-streaming bands enthusiasm and inventiveness of Roundhouse staff, from the Main Space, and 15 teenagers creating and especially in these challenging economic times. And, performing The Dark Side of Love as part of the World led by Marcus, they’ve shown that they possess the Shakespeare Festival, the participation of young people skills, experience and ambition to keep developing this is an essential element of the Roundhouse experience. wonderful organisation. Every year we work with thousands of 11–25 year-olds It only remains for me to thank everyone who, in one – many of whom have been excluded, marginalised or way or another, enables the Roundhouse to keep doing disadvantaged by society – offering them a chance to such extraordinary work and reaching out to so many discover the sheer joy of participating in the arts, find young people: Arts Council England for their continued their way back into education, gain confidence or, in funding; the many companies, trusts, foundations and some cases, truly transform their lives. -

Using Historical GIS to Describe Changes in the Sydney and Melbourne Live Music Scenes

GSR_3 Geospatial Science Research 3. School of Mathematical and Geospatial Science, RMIT University December 2014 “A band on every corner”: Using historical GIS to describe changes in the Sydney and Melbourne live music scenes Sarah Taylor1, Colin Arrowsmith1 and Nicole Cook2 1School of Mathematical and Geospatial Science, RMIT University, Australia 2Department of Resource Management and Geography, The University of Melbourne, Australia Email: [email protected] Key words: Historical GIS; historical geodatabase; live music; Melbourne; Sydney Abstract This paper demonstrates the use of historical Geographic Information Systems (historical GIS) to investigate live music in Sydney and Melbourne. It describes the creation of a tailored historical geodatabase built from samples of gig listings (comprising dates, locations, and performer names), and how this historical geodatabase offers insight into the changing dynamics of performers and venue locations. The major findings from the analyses using the developed historical geodatabase are that neither city showed a decline in live music performance or performer numbers, but Melbourne increased at a greater rate than Sydney. Further, the spatial concentration within Melbourne has been far greater than that for Sydney. While Melbourne has expanded numerically but shrunk spatially, Sydney has experienced a geographic dispersion of performances throughout the study period. Introduction This paper demonstrates the use of historical Geographic Information Systems (historical GIS) to investigate live music in Sydney and Melbourne. It describes the creation of a tailored historical geodatabase built from samples of gig (concert) listings comprising dates, locations, and performer names. It then presents descriptive statistics and thematic maps derived from this historical geodatabase, demonstrating how this offers insight into the changing dynamics of live music performers and venue locations. -

Bare Facts, Issue No. 890, 08.11.1996

4 The Issue University of No. 890 Surrey's Student Magazine 8th November 1996 £15 Photocopy Bargain Revealed few weeks ago, it was design or architecture courses stu- lege buildings, and with few books revealed that hidden dents will pay out around £800 per left in libraries. Fees will be the nail course fees of £15 were year on extra course costs. Hidden in the coffin of access to éducation, A Course Costs, the NUS research but who would pay for such a dev- being charged to Surrey Economies Students for report to be published later this astated éducation system? We are photocopies and other course month draws on the results of a aheady paying out enough. We are material. However, compared to country-wide survey of university subsidismg the universities to the departments last summer. tuneof£171 million per year. Ifthe average hidden course costs in top up fees are introduced this will other universities, this is a real Yesterday, students across the coimtry demonstrated for National mean students and their parents bargain. The findings of a NUS paying out a further £300 million." survey, to be published later this No Fees Day in protest at threat- month, show that Britain's ened top-up fees and up to £1000 300,000 undergraduates are a year registration by university aiready forced to pay up over £ 171 heads. NUS announced the results of a ballot of student unions, million a year in hidden course showing unanimous support of the costs. The news comes as students Higher Education Shutdown by across the country join National the teaching trade unions, who No Fees Day (November 5th) to will announce the result of their protest against a possible £1,000 ballot on Friday 8th November. -

“You Went There for the People and Went There for the Bands”

“You went there for the people and went there for the bands” The Sandringham Hotel – 1980 to 1998 Brendan Paul Smyly Doctor of Philosophy University of Western Sydney August 2010 2 Acknowledgements I offer thanks to my supervisors, principally Dr Diana Blom whose knowledge, good advise and enthusiasm for a broad array of topics was invaluable for the length of this study. To Dr Greg Noble, a serendipitous choice who provided great counsel at the oddest hours and introduced me to whole vistas of academic view, thank you. Also to Professor Michael Atherton who offered unwavering support (along with some choice gigs) over the years of my engagement with UWS, many thanks. I offer very special thanks to all my colleagues from the Music Department at UWS. Ian Stevenson and Dr Sally Macarthur, thank you for your faith and support. To John Encarnacao, who was also an interviewee for the project, your advice and enthusiasm for the project has been invaluable and saw me through some difficult months, as has your friendship, thank you. To Mitchell Hart, your knowledge and willingness to help with myriad tasks whenever asked is greatly appreciated. My time as a student in this department will be fondly remembered due to you people being there. Many thanks to the administrative staff of the School of Communication Arts, particularly Robin Mercer for candidature funding and travel advice, and Tracy Mills at the Office of Research Service for your prompt and valuable help. Above all, I wish to thank Darinca Blajic. Thank you for your unfailing love, support and wonderful food.