Darcus Howe: a Political Biography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Joys of Advertisements Istorians and Others Who Study Suschitzky’S Bookshop Libris at 38 Boundary in 1968

VOLUME 15 NO.3 MARCH 2015 journal The Association of Jewish Refugees The joys of advertisements istorians and others who study Suschitzky’s bookshop Libris at 38 Boundary in 1968. Its second branch, just off Finchley patterns of consumption have long Road, a mecca for scholars and connoisseurs Road facing the side of what is now Waitrose been aware of the importance of of German books. Well known in its time was John Barnes, opened in 1956 and survived Hadvertisements as rich sources of material; the Blue Danube Club at 153 Finchley Road, into the 21st century. Gideon Reuveni of the Centre for German- where Peter Herz directed Continental-style Refugee businesses in this part of London Jewish Studies at the University of Sussex, for reviews until he returned to his native Vienna catered to their clients’ needs across the example, has published fascinating work on in 1953; the Blue Danube Club was itself board of everyday life. In the sphere of office the Jews of Germany as consumers in the pre- an offshoot of another Kleinkunstbühne, the equipment, A. Breuer of 43 Buckland Crescent Hitler era. As I have myself learnt a great deal small-stage cabaret theatre Das Laterndl (The specialised in the repair and maintenance of about the community of Jewish refugees from Lantern), which had been set up at 69 Eton typewriters, while Ernst Rosenthal of 92 Eton Nazism in Britain from the ads in the back Avenue by the wartime Austrian Centre. Place, Eton College Road, offered ‘photocopies issues of AJR Information, I was intrigued by The distinctively Continental atmosphere in the middle of Hampstead’. -

Darcus Howe: a Political Biography

Bunce, Robin, and Paul Field. "Authors' Preface." Darcus Howe: A Political Biography. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2014. viii–x. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 29 Sep. 2021. <>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 29 September 2021, 20:11 UTC. Copyright © Robin Bunce and Paul Field 2014. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. Authors ’ Preface Writing this book has involved many wonderful experiences. Hours in archives are, of course, the historian ’ s delight, and we thank the staff at the National Archives, the Institute of Race Relations, the George Padmore Institute, the British Library, the Colindale Newspaper Archive, Warwick University Library, Cambridge University Library, the Butler Library at the Columbia University and the archives of the Oilfi eld Workers Trade Union of Trinidad and Tobago, to name but a few. We have spent many hours being entertained by our interviewees. Early on in the project, we had the good fortune to spend an aft ernoon with Farrukh Dhondy. ‘ I expect you want me to tell you all the scandal, ’ was his opener. We earnestly assured him that we were writing a serious political piece, adding that we couldn ’ t believe that there would be enough scandal to fi ll a single page. ‘ Th ere ’ s enough to fi ll seven volumes! ’ , he retorted. One of the stranger experiences, only obliquely related to the project, was an Equality and Diversity training session that one of us was compelled to attend in the summer of 2011. -

Decolonising Knowledge

DECOLONISING KNOWLEDGE Expand the Black Experience in Britain’s heritage “Drawing on his personal web site Chronicleworld.org and digital and print collection, the author challenges the nation’s information guardians to “detoxify” their knowledge portals” Thomas L Blair Commentaries on the Chronicleworld.org Users value the Thomas L Blair digital collection for its support of “below the radar” unreported communities. Here is what they have to say: Social scientists and researchers at professional associations, such as SOSIG and the UK Intute Science, Engineering and Technology, applaud the Chronicleworld.org web site’s “essays, articles and information about the black urban experience that invite interaction”. Black History Month archived Bernie Grant, Militant Parliamentarian (1944-2000) from the Chronicleworld.org Online journalists at the New York Times on the Web nominate THE CHRONICLE: www.chronicleworld.org as “A biting, well-written zine about black life in Britain” and a useful reference in the Arts, Music and Popular Culture, Technology and Knowledge Networks. Enquirers to UK Directory at ukdirectory.co.uk value the Chronicleworld.org under the headings Race Relations Organisations promoting racial equality, anti- racism and multiculturalism. Library”Govt & Society”Policies & Issues”Race Relations The 100 Great Black Britons www.100greatblackbritons.com cites “Chronicle World - Changing Black Britain as a major resource Magazine addressing the concerns of Black Britons includes a newsgroup and articles on topical events as well as careers, business and the arts. www.chronicleworld.org” Editors at the British TV Channel 4 - Black and Asian History Map call the www.chronicleworld.org “a comprehensive site full of information on the black British presence plus news, current affairs and a rich archive of material”. -

Phil Cohen, Reading Room Only: Memoir of a Radical Bibliophile And

Phil Cohen, Reading Room Only: Memoir of a Radical Bibliophile, hardback, 274 pages, Nottingham: Five Leaves, 2013. ISBN: 978-1907869785; £14.99. and Sophie Parkin, The Colony Room Club: A History of Bohemian Soho, 1948-2006, hardback, 265 pages, London: Palmtree Publishers, 2012. ISBN: 978-0957435407; £35. Reviewed by James Heartfield (Freelance, UK) The Literary London Journal, Volume 12 Number 1–2 (Spring/Autumn 2015) Bloomsbury and Soho in the nineteenth century were places where political refugees lived, though the Germans preferred Bloomsbury, just to the north, on the grounds that the Parisians of Soho were all drunks and womanisers. Phil Cohen is a long-standing activist and now academic, who has written his memoir of radical Bloomsbury, while writer and club manager Sophie Parkin’s history of drinking clubs takes Soho as its epicentre, and in particular the Colony Club on Dean Street. Phil Cohen was sent to St Paul’s School and later Oxford, but his attention was taken up by the London of Somerstown and Bloomsbury. As a youth worker, he wandered through the radical 1960s, being involved in various movements of the Fluxus and Situationist art scene that he met in bookshops like Better Books, India, and later Gay’s the Word, and working for a while as an assistant to the surrealist John Latham. He participated in the radical psychoanalytic movement led by R. D. Laing, paying for his treatment with more youth work, and then took part in the Dialectic of Liberation conference with Black Power’s Stokely Carmichael, New Leftist Herbert Marcuse and Beat poet Allen Ginsberg at the Roundhouse in 1967. -

Kristine Stiles

Concerning Consequences STUDIES IN ART, DESTRUCTION, AND TRAUMA Kristine Stiles The University of Chicago Press Chicago and London KRISTINE STILES is the France Family Professor of Art, Art Flistory, and Visual Studies at Duke University. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2016 by Kristine Stiles All rights reserved. Published 2016. Printed in the United States of America 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 12345 ISBN13: 9780226774510 (cloth) ISBN13: 9780226774534 (paper) ISBN13: 9780226304403 (ebook) DOI: 10.7208/chicago/9780226304403.001.0001 Library of Congress CataloguinginPublication Data Stiles, Kristine, author. Concerning consequences : studies in art, destruction, and trauma / Kristine Stiles, pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 9780226774510 (cloth : alkaline paper) — ISBN 9780226774534 (paperback : alkaline paper) — ISBN 9780226304403 (ebook) 1. Art, Modern — 20th century. 2. Psychic trauma in art. 3. Violence in art. I. Title. N6490.S767 2016 709.04'075 —dc23 2015025618 © This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper). In conversation with Susan Swenson, Kim Jones explained that the drawing on the cover of this book depicts directional forces in "an Xman, dotman war game." The rectangles represent tanks and fortresses, and the lines are for tank movement, combat, and containment: "They're symbols. They're erased to show movement. 111 draw a tank, or I'll draw an X, and erase it, then redraw it in a different posmon... -

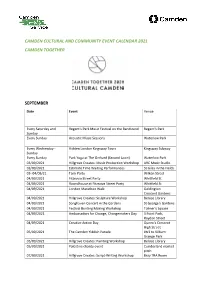

Camden Cultural and Community Event Calendar 2021 Camden Together

CAMDEN CULTURAL AND COMMUNITY EVENT CALENDAR 2021 CAMDEN TOGETHER SEPTEMBER Date Event Venue Every Saturday and Regent's Park Music Festival on the Bandstand Regent's Park Sunday Every Sunday Acoustic Music Sessions Waterlow Park Every Wednesday - Hidden London Kingsway Tours Kingsway Subway Sunday Every Sunday Park Yoga at The Orchard (Second Lawn) Waterlow Park 03/09/2021 Hillgrove Creates: Music Production Workshop ARC Music Studio 03/09/2021 Estimate Time Waiting Performances St Giles in the Fields 03- 04/09/21 Tank Party Wilken Street 04/09/2021 Fitzrovia Street Party Whitfield St 04/09/2021 Roundhouse at Fitzroiva Street Party Whitfield St 04/09/2021 London Marathon Walk Goldington Crescent Gardens 04/09/2021 Hillgrove Creates: Sculpture Workshop Belsize Library 04/09/2021 Songhaven Concert in the Gardens St George's Gardens 04/09/2021 Festival Bunting Making Workshop Tolmer's Square 04/09/2021 Ambassadors for Change, Changemakers Day 3 Point Park, Raydon Street 04/09/2021 Creative Action Day Queen's Crescent High Street 05/09/2021 The Camden Yiddish Parade JW3 to Kilburn Grange Park 05/09/2021 Hillgrove Creates: Painting Workshop Belsize Library 05/09/2021 Palestine charity event Cumberland market pitch 07/09/2021 Hillgrove Creates: Script-Writing Workshop Bray TRA Room 07/09/2021 Hillgrove Creates: Music Production Workshop ARC Music Studio 08/09/2021 Hillgrove Creates: Music Production Workshop ARC Music Studio 09/09/2021 Hillgrove Creates: Theatre Performance Belsize Library Workshop 09/09/2021 Hillgrove Creates: Music Production -

Game Reserves, Murder, Afterlives: Grace A

This is a repository copy of Game Reserves, Murder, Afterlives: Grace A. Musila’s A Death Retold in Truth and Rumour. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/121047/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Nicholls, BL (2017) Game Reserves, Murder, Afterlives: Grace A. Musila’s A Death Retold in Truth and Rumour. Eastern African Literary and Cultural Studies, 3 (2-4). pp. 184-199. ISSN 2327-7408 https://doi.org/10.1080/23277408.2017.1343006 © 2017 Brendon Nicholls. This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in Eastern African Literary and Cultural Studies on 11th October 2017, available online: https://doi.org/10.1080/23277408.2017.1343006. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ 1 Brendon Nicholls Game Reserves, Murder, Afterlives: Grace A. Musila’s A Death Retold in Truth and Rumour At the end of Ngg wa Thiong’o’s Petals of Blood, a young woman called Akinyi visits Karega, a trade unionist imprisoned on suspicion of communism by the Kenyatta regime. -

VS. Naipauñ "The Return of Eva Perón " and the Loss of "True Wonder

VS. Naipauñ "The Return of Eva Perón " and the Loss of "True Wonder TRACY WARE ... the experience of wonder continually reminds us that our grasp of the world is incomplete. STEPHEN GREENBLATT, Marvelous Possessions IN "CONRAD'S DARKNESS," the concluding essay in The Return of Eva Perón, V. S. Naipaul laments the decay of Joseph Conrad's aesthetic ideals: The novelist, like the painter, no longer recognizes his interpretive function; he seeks to go beyond it; and his audience diminishes. And so the world we inhabit, which is always new, goes by unexamined, made ordinary by the camera, unmeditated on; and there is no one to awaken the sense of true wonder. (245) As a "fair definition of the novelist's purpose, in all ages" (245), this passage seems at least partially at odds with Naipaul's own increasingly bleak fiction and with his achievement in this vol• ume. Here, in penetrating and contentious analyses of Third World corruption, he fulfills his own demands for examination, meditation, and interpretation, if not for wonder. Though he subordinates these essays to the thematically similar novels he wrote later ( Guerrillas and A Bend in the River), though he claims no "further unity" than comes from "intensity" and an "obses• sional nature" ("Author's Note"), the book is ideologically con• sistent and intricately designed: each essay offers "a vision of the world's half-made societies as places which continuously made and unmade themselves" (233), to borrow Naipaul's account of Nostromo; each of the first three essays has an apt citation from ARIEL: A Review of International English Literature, 24:2, April 1993 102 TRACY WARE Conrad, whom the last essay considers at length. -

Roundhouse Access Guide 1. Introduction 2. Contact Details 3

Roundhouse Access Guide 1. Introduction 2. Contact Details 3. Venue Description 4. Bookable Access Facilities 5. How to apply 6. Travel Guide 7.1 By Tube 7.2 By Overground 7.3 By Bus 7.4 By Coach 7.5 By CarArrival Guide 7. Toilets 8. Customers with Medical Requirements 9. Access to Performance 9.1 Facilities for Deaf and Hard of Hearing Patrons 9.2 Facilities for Blind or Vision-Impaired Visitors 9.3 Venue Accessibility for Wheelchair Users 9.4 Relaxed Performances at the Roundhouse 10. Assistance Dogs 11. Strobe Lighting ///////////////////////////////////////////////// 1. Introduction We’re committed to making all aspects of your visit to the Roundhouse enjoyable, universally welcoming and physically accessible and are proud to have been awarded a Gold Standard Award from Attitude is Everything, recognising our on-going commitment to provide the best possible experience for deaf and disabled visitors ///////////////////////////// 2. Contact Details To discuss any access-related enquiries, please don’t hesitate to contact us: [email protected] www.roundhouse.org.uk 0300 6789 222, Option 3 (Roundhouse Access Enquiries and Accessible Ticket Purchasing) Roundhouse, Chalk Farm Road, London, NW1 8EH We will endeavor to respond to your enquiries as soon as possible. Generally speaking, this will be within 24 hours, though postal responses and requests received outside workings hours (weekends and holidays) may take a little longer. //////////////////////////////////// 3. Venue Description The Roundhouse has step free (lift) access to Accessible Toilets, Bars and Performance Spaces on all levels as well as level access to the Box Office, MADE Bar and Kitchen and Paul Hamlyn Roundhouse Studios on Level 0. -

Restaurants British French Italian Greek

11 6 RESTAURANTS BRITISH Freud 1. ODETTE’S Museum 130 Regents Park Road NW1 8XL Tel. 020 7586 8569 FRENCH TOP LOCAL ATTRACTIONS 2. BRADLEYS 25 Winchester Road 9 NW3 3NR Tel. 020 7722 3457 ENTERTAINMENT & SPORTS 3. L’ABSINTHE VENUES Hampstead Chalk 40 Chalcot Road Theatre Farm Roundhouse NW1 8LS Tel. 020 7843 4848 Regent’s Park Open Air Theatre Swiss ITALIAN Roundhouse 19 Camden CoƩage 18 4. VILLA BIANCA Lord's Cricket Ground 2 Market Jason’sJa Trip 1 Perrin’s Court, Hampstead //London NW3 1QS Tel. 020 7435 3131 Hampstead Theatre 5. J PIZZERIA AND CUCINA 17 WWaterbus 10 7 148 Regents Park Road PARKS & OUTDOOR ACTIVITIES 13 NW1 8XN Tel. 020 7586 9100 5 6. ARTIGIANO Regent's Park 12A Belsize Terrace Primrose Hill South 14 1 NW3 4AX Tel. 020 7794 4288 Primrose 16 15 Camden GREEK ZSL London Zoo Hampstead Hill Lock Camden 3 Town 7. LEMONIA Jason’s Trip - Canal Tours 89 Regents Park Road London Waterbus Company - Boat Trips NW1 8UY Tel. 020 7586 7454 CHINESE 8. ROYAL CHINA CLUB SHOPS & MARKETS 40-42 Baker Street Camden Market W1U 7AJ Tel. 020 7486 3898 9. CHINA GARDEN Camden Lock 5-6 New College Parade NW3 5EP Tel. 020 7722 9552 MUSEUMS & LANDMARKS The Jewish MALAYSIAN Museum Madame Tussauds 10. SINGAPORE GARDEN ZSL London 83 Fairfax Road Freud Museum Zoo NW6 4DY Tel. 020 7328 5314 The Jewish Museum Mornington INDIAN Crescent 11. HAZARA Abbey Road Studios & Crossing St. John’s 44 Belsize Lane Wood NW3 5AR Tel. 020 7433 1147 STEAKHOUSE FOR MORE ATTRACTIONS, 12. -

This Issue Is Dedicated to the Memory of John La Rose, Founder of New Beacon Books

EnterText 6.3 Dedication and Introduction This issue is dedicated to the memory of John La Rose, founder of New Beacon Books, London. He lived to see the fortieth anniversary, in 2006, of the publishing house—or maisonette, as he sometimes called it, wryly—bookshop and cultural centre he had established. Having come to London from Trinidad in the early 1960s, he always had the intention to start a bookshop in the British capital because he understood how important ideas are if we are to act on our dreams of changing the world. And it was this phrase, so often on his lips, which Horace Ove chose as the title for his feature film about John La Rose’s life, Dream to Change the World (2005). In the intervening decades since its foundation, New Beacon’s impact on the cultural map of Britain, the Caribbean and the wider world has acquired real significance, not least as a bright beacon of what a few individuals can achieve with intelligence, passion and dedication (not money, which nowadays tends to be seen as the only prerequisite). New Beacon was named after the Beacon political movement of 1930s Trinidad, which was associated with the slogan “Agitate! Educate! Federate!” While these words have a particular resonance in Trinidad, of course, they also echo round the wider Anglophone Caribbean, where the West Indies Federation, which had promised a realisation of the dreams of John’s generation, lasted so few years, from 1958 to 1962. And they remain resonant on the global stage, reminding us, as they do, of the need to Paula Burnett: Dedication and Introduction 3 EnterText 6.3 rouse ordinary people’s awareness and feelings, to deepen dialogue and understanding, and to co-operate with one another if our puny individualities are to be able to exert real influence. -

Looking at the BUFP &

Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line Independent radical black politics: Looking at the BUFP & BLF First Published: October 2017. https://wordpress.com/post/woodsmokeblog.wordpress.com/1499 Transcription, Editing and Markup: Sam Richards and Paul Saba Copyright: This work is in the Public Domain under the Creative Commons Common Deed. You can freely copy, distribute and display this work; as well as make derivative and commercial works. Please credit the Encyclopedia of Anti‐Revisionism On‐Line as your source, include the url to this work, and note any of the transcribers, editors & proofreaders above. There is a history after Empire Windrush docking in 1948. Since then the involvement of black Britons in the assertion of their own equality in post-war Britain receives little recognition or acknowledgement. There is a rich vein to explore and acknowledge with the varied and complex history of self-organizing within different minority communities that have help shaped British society through expression of their political awareness, active democracy and involvement against the racism of state and society, raising the demands for equality and justice. Even a narrow focus on any decade in recent British history brings to light a varied and complicated history of struggles for civil rights and justice to be respected in terms of family rights, immigration, employment, defence of communities from racist attacks and policing that was as vibrant and heroic as its American counterpart. The organisation of independent and emphatic opposition