Testing for Channels of Persuasion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Separations-06-00017-V2.Pdf

separations Article Perfluoroalkyl Substance Assessment in Turin Metropolitan Area and Correlation with Potential Sources of Pollution According to the Water Safety Plan Risk Management Approach Rita Binetti 1,*, Paola Calza 2, Giovanni Costantino 1, Stefania Morgillo 1 and Dimitra Papagiannaki 1,* 1 Società Metropolitana Acque Torino S.p.A.—Centro Ricerche, Corso Unità d’Italia 235/3, 10127 Torino, Italy; [email protected] (G.C.); [email protected] (S.M.) 2 Università di Torino, Dipartimento di Chimica, Via Pietro Giuria 5, 10125 Torino, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondences: [email protected] (R.B.); [email protected] (D.P.); Tel.: +39-3275642411 (D.P.) Received: 14 December 2018; Accepted: 28 February 2019; Published: 19 March 2019 Abstract: Per and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) are a huge class of Contaminants of Emerging Concern, well-known to be persistent, bioaccumulative and toxic. They have been detected in different environmental matrices, in wildlife and even in humans, with drinking water being considered as the main exposure route. Therefore, the present study focused on the estimation of PFAS in the Metropolitan Area of Turin, where SMAT (Società Metropolitana Acque Torino S.p.A.) is in charge of the management of the water cycle and the development of a tool for supporting “smart” water quality monitoring programs to address emerging pollutants’ assessments using multivariate spatial and statistical analysis tools. A new “green” analytical method was developed and validated in order to determine 16 different PFAS in drinking water with a direct injection to the Ultra High Performance Liquid Chromatography tandem Mass Spectrometry (UHPLC-MS/MS) system and without any pretreatment step. -

Orari E Percorsi Della Linea Bus 3107

Orari e mappe della linea bus 3107 3107 Brusasco Visualizza In Una Pagina Web La linea bus 3107 (Brusasco) ha 16 percorsi. Durante la settimana è operativa: (1) Brusasco: 13:10 - 17:25 (2) Casalborgone Scuole: 07:35 - 14:30 (3) Chivasso Istituto Ubertini: 09:10 - 13:20 (4) Chivasso Movicentro: 08:15 (5) Chivasso Movicentro: 06:50 - 12:10 (6) Chivasso Via Po: 09:10 - 19:35 (7) Chivasso Via Po: 05:15 - 21:20 (8) Gassino: 10:20 - 17:50 (9) Piana San Raffaele: 13:50 - 17:20 (10) Piovà Massaia: 17:55 (11) Torino Via Fiochetto: 06:05 - 22:15 Usa Moovit per trovare le fermate della linea bus 3107 più vicine a te e scoprire quando passerà il prossimo mezzo della linea bus 3107 Direzione: Brusasco Orari della linea bus 3107 65 fermate Orari di partenza verso Brusasco: VISUALIZZA GLI ORARI DELLA LINEA lunedì 13:10 - 17:25 martedì 13:10 - 17:25 Torino (Via Fiochetto - Autostazione Dora) 30 Lungo Dora Savona, Torino mercoledì 13:10 - 17:25 Pisa giovedì 13:10 - 17:25 109 Lungo Dora Firenze, Torino venerdì 13:10 - 17:25 Gtt Stabilimento Tortona sabato 13:10 - 15:30 54/E Corso Tortona, Torino domenica 06:55 - 17:30 Tortona 28 Corso Belgio, Torino Chieti 60/D Corso Belgio, Torino Informazioni sulla linea bus 3107 Direzione: Brusasco Brianza Fermate: 65 96 /B Corso Belgio, Torino Durata del tragitto: 75 min La linea in sintesi: Torino (Via Fiochetto - Cadore Autostazione Dora), Pisa, Gtt Stabilimento Tortona, 166 Corso Belgio, Torino Tortona, Chieti, Brianza, Cadore, Pasini, Mongreno, Sassi-Superga, Cafasso, Casale N.472, Croce, Pasini Pescatori, Delle Pietre, La Valle, Diaz, Casale N.33, Piazza Alberto Pasini, Torino San Mauro (Scambio Peso), San Mauro (Sambuy), Castiglione (Molino), Castiglione (Pedaggio), Mongreno Castiglione (Fornace), Castiglione (Rezza), 310 Corso Casale, Torino Castiglione (Sant' Eufemia), Gassino (Circonvallazione / Diaz), Gassino (Centro), Gassino Sassi-Superga (Sobrero), Gassino (V. -

Provincia Di Alessandria Determinazione Dirigenziale N

REGIONE PIEMONTE BU47 24/11/2011 Provincia di Alessandria Determinazione Dirigenziale n. 494/130339 del 02/11/2011 che autorizza in via provvisoria le concessioni preferenziali comprese nell’elenco allegato (5° elenco). DIPARTIMENTO AMBIENTE TERRITORIO E INFRASTRUTTURE DIREZIONE AMBIENTE E PIANIFICAZIONE L’anno 2011 il giorno 2 del mese di Novembre, nella sede provinciale di Via Galimberti n. 2/A, 15121 Alessandria Il sottoscritto Ing. Claudio Coffano, Dirigente della Direzione Ambiente e Pianificazione Vista la D.G.P. n. 28/10470 del 26/01/2011 ad oggetto:“Modifica regolamento sull’ordinamento degli uffici e dei servizi parte I – Regolamento di organizzazione”; Vista la D.G.P. n. 29/10483 del 26/01/2011 ad oggetto “Macrostruttura provinciale. Approvazione”; Visto il Decreto del Presidente della Provincia n. 134/11847 del 31/01/2011 con il quale è stato affidato l’incarico dirigenziale relativo alla Direzione Ambiente e Pianificazione; Visto l’Ordine di Servizio n. 5/2011 prot. 116478 del 30/09/2011 ad oggetto “Piano esecutivo di gestione 2011 Direzione Ambiente e Pianificazione individuazione servizi e uffici collocazione personale, individuazione responsabili dei procedimenti – endoprocedimenti e attività di certificazione e gestione banche dati” che dispone circa l’organizzazione interna della Direzione; Visto l’art. 107 del Decreto Legislativo 267/2000 “Funzioni e responsabilità della dirigenza”; Visto l’art. 53 dello Statuto della Provincia di Alessandria “Funzioni e compiti dei Dirigenti”; Visto l’art. 4 del Decreto Legislativo 30 marzo 2001 n. 165; Visti gli artt. 183 e 184 del Decreto Legislativo 18 agosto 2000 n. 267; Richiamati: - il T.U. 11/12/1933 n. -

Albo Dei Medici Chirurghi

ORDINE PROVINCIALE DEI MEDICI CHIRURGHI E DEGLI ODONTOIATRI DI VC C.so MAGENTA, 1 - 13100 VERCELLI Tel. 0161256256 - Fax 0161256156 Albo dei Medici Chirurghi Aggiornato al: 18/01/2018 Totale nominativi: 819 Pagina 1 di 78 A Cod. Medici Cod. Odont. Nominativo Cittadinanza Luogo di nascita Laurea Altre competenze Data att.le iscr. Data att.le iscr. Domicilio Codice Enpam Data di nascita Data e luogo Laurea I° Iscr. Medici I° Iscr. Odont. CAP Comune Cod. fisc. Anno, luogo e sessione Abil. Qualifiche Libera docenza Titoli accademici Master 02106 ABBAGNANO ANTONELLA ITALIA VERCELLI (VC) LAUREA MED. 08/07/1988 VIA LULLO 63 300137878U 30/01/1961 25/03/1988 (PV) 08/07/1988 (VC) 13100 VERCELLI BBGNNL61A70L750P 1988 (PV) - 1 - medico generico 02669 ABELLI GIANFRANCO ITALIA VERCELLI (VC) LAUREA MED. 21/03/2005 C.SO VERCELLI 151 300163096J 11/01/1964 27/09/1990 (PV) 21/02/1991 (NO) 13011 BORGOSESIA BLLGFR64A11L750C 1990 (PV) - 2 SCIENZA STATISTICA DELL'ALIMENTAZIONE SANITARIA 01170 ACANFORA FERDINANDO ITALIA VERCELLI (VC) LAUREA MED. 06/03/1974 VIA DANTE 80 010014140C 08/04/1948 16/11/1973 (PV) 06/03/1974 (VC) 13100 VERCELLI CNFFDN48D08L750D 1974 (PV) - 1 - ospedaliero UROLOGIA ONCOLOGIA 02680 ADEM CHARBEL ITALIA BAUCHRIEH (LIBANO) LAUREA MED. 28/11/2005 VIA CERRONE 10 300222195M 02/09/1966 29/06/1995 (MI) 28/11/2005 (VC) 13100 VERCELLI DMACRB66P02Z229J 1995 (MI) - 2 PEDIATRIA 02701 AGUGGIA LUCA ITALIA VERCELLI (VC) LAUREA MED. 05/03/2007 VIA GALILEO FERRARIS 300297121N 25/11/1981 24/10/2006 (NO) 25 05/03/2007 (VC) 13100 VERCELLI GGGLCU81S25L750X 2007 (NO) - 1 01206 AGUGGIA MAURO ITALIA VERCELLI (VC) LAUREA MED. -

Prospetto Allegato

PROVINCIA SIGLA CODICE ENTE ENTE IMPORTO ALESSANDRIA AL 1010020090 ARQUATA SCRIVIA 30.595,27 ALESSANDRIA AL 1010020380 CASALE MONFERRATO 48.130,21 ALESSANDRIA AL 1010021110 NOVI LIGURE 4.259,97 ALESSANDRIA AL 1010021510 SAN SALVATORE MONFERRATO 32.007,64 ALESSANDRIA AL 1010021710 TORTONA 33.142,90 ASTI AT 1010070050 ASTI 30.958,41 BIELLA BI 1010960040 BIELLA 25.719,85 BIELLA BI 1010960710 VALDENGO 43.123,61 BIELLA BI 1010960770 VIGLIANO BIELLESE 28.631,34 CUNEO CN 1010270030 ALBA 5.465,46 CUNEO CN 1010270780 CUNEO 64.885,82 NOVARA NO 1010521000 NOVARA 49.198,50 TORINO TO 1010810570 CARIGNANO 15.304,44 TORINO TO 1010810580 CARMAGNOLA 31.889,82 TORINO TO 1010810800 CHIVASSO 32.377,43 TORINO TO 1010810880 COLLEGNO 34.504,29 TORINO TO 1010811180 GRUGLIASCO 29.456,97 TORINO TO 1010812090 RIVAROLO CANAVESE 31.300,33 TORINO TO 1010812550 SETTIMO TORINESE 24.358,84 TORINO TO 1010812620 TORINO 601.191,34 VERBANO-CUSIO-OSSOLA VB 1011020570 PREMOSELLO-CHIOVENDA 15.450,00 VERCELLI VC 1010881360 SERRAVALLE SESIA 30.531,22 BERGAMO BG 1030120200 BARIANO 28.103,81 BERGAMO BG 1030120240 BERGAMO 64.700,58 BERGAMO BG 1030120860 CURNO 30.503,16 BERGAMO BG 1030121220 LOVERE 31.999,29 BERGAMO BG 1030121730 ROMANO DI LOMBARDIA 5.381,30 BRESCIA BS 1030150260 BRESCIA 66.529,42 BRESCIA BS 1030150600 DARFO BOARIO TERME 16.397,84 BRESCIA BS 1030150620 DESENZANO DEL GARDA 7.853,36 COMO CO 1030240720 COMO 88.371,39 COMO CO 1030241380 MASLIANICO 33.163,82 COMO CO 1030241510 MONTORFANO 25.176,14 LECCO LC 1030980130 CALOLZIOCORTE 30.300,43 LECCO LC 1030980420 LECCO 29.380,24 -

Deliberazione Della Giunta Regionale 1 Marzo 2019, N. 26-8491

REGIONE PIEMONTE BU12 21/03/2019 Deliberazione della Giunta Regionale 1 marzo 2019, n. 26-8491 Definizione degli ambiti territoriali di scelta dell' ASL AL entro i quali l'assistito puo' esercitare il proprio diritto di scelta/revoca del medico di assistenza primaria. A relazione del Presidente Chiamparino: Visto l’art. 19, comma 2, della Legge n. 833/78 che prevede la possibilità di libera scelta del medico, da parte dell’assistibile, nei limiti oggettivi dell’organizzazione sanitaria; visto l’art. 33, comma 3, dell’Accordo Collettivo Nazionale per la disciplina dei rapporti con i Medici di Medicina generale del 23 marzo 2005 e s.m.i. (nel prosieguo ACN MMG) che conferisce alle Regioni la competenza ad articolare il livello organizzativo dell’assistenza primaria in ambiti territoriali di comuni, gruppi di comuni o distretti; dato atto che attualmente l’ASL AL è articolata in 4 Distretti qui di seguito elencati: • Distretto di Acqui Terme-Ovada (risultante dalla fusione dell’ ex Distretto di Acqui -Terme con l’ ex Distretto di Ovada); • Distretto di Alessandria-Valenza (risultante dalla fusione dell’ ex Distretto di Alessandria con l’ ex Distretto di Valenza); • Distretto di Casale Monferrato; • Distretto di Novi Ligure- Tortona (risultante dalla fusione dell’ ex Distretto di Novi Ligure con l’ ex Distretto di Tortona); preso atto della deliberazione n. 782 del 28 novembre 2018, a firma del Direttore Generale dell'ASL AL (agli atti della Direzione Sanità, Settore Sistemi organizzativi e Risorse umane del SSR) nella quale viene posto in evidenza che: a) con legge regionale n. 4 del 5 aprile 2017 è stato istituito, con decorrenza dal 1° gennaio 2018, il Comune di Cassano Spinola , afferente il Distretto di Novi Ligure-Tortona, risultante dalla fusione dei Comuni di Cassano Spinola e di Gavazzana; b) con legge regionale n. -

Allegato Sub B Gestore A.M.C. S.P.A

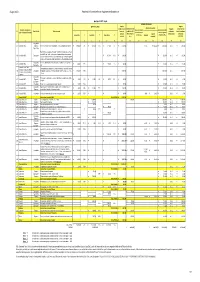

Allegato Sub B Piano Stralcio Triennale (2007-2009) - Aggiornamento Dicembre 2008 Gestore A.M.C. S.p.A QUADRO FINANZIARIO IMPORTO LAVORI Importo Importo complessivo dei Contributi di fonti Altre fonti finanziarie Soggetto complessivo dei Territorio comunale nel Interventi attivati Interventi attivabili N° Fase del ciclo Titolo intervento lavori sul pubbliche (UE, realizzatore lavori da realizzare quale si sviluppa l'intervento con mutui accesi a cura del gestore territorio Stato, Regioni, Importo dell'intervento nel triennio Acquedotto % Fognatura % Depurazione %dal comune Soggetto -Tramite Tariffa- comunale etc.) disponibile 2007÷2009 1 2 3 4 56789101112131415161718 Acquedotto 001 Comuni di A.M.C. Fognatura Interventi di manutenzione straordinaria e rinnovo/ampliamento impianti € 2.990.000 56% € 1.879.000 35% € 471.000 9% € 5.340.000 A.M.C. € 1.040.000 € 4.300.000 A.M.C. € 5.340.000 Depurazione Realizzazione e adeguamento impianti di trattamento delle acque reflue ai sensi del D.Lgs 152/06 (realizzazione di impianti di depurazione presso i 004 Comuni di A.M.C. Depurazione € 200.000 100% € 200.000 € 200.000 A.M.C. € 200.000 comuni e i nuclei frazionali dei comuni attualmente sprovvisti di tali impianti; revisione ed adeguamento degli impianti di piccole dimensioni già esistenti) Acquedotto Interventi volti al miglioramento energetico e alla riduzione delle perdite in 217 Comuni di A.M.C. € 350.000 88% € 50.000 13% € 400.000 € 400.000 A.M.C. € 400.000 Depurazione rete Comuni di: Casale M.to, Collegamento acquedottistico tra Casale Monferrato e i comuni di Caresana, Caresana, Costanzana, Motta 200 Acquedotto Stroppiana, Costanzana, Pezzana, Motta dè Conti e Pertengo – Vercelli – € 2.000.000 100% € 2.000.000 € 2.000.000 A.M.C. -

Sub Ambito 01 – Alessandrino Istat Comune 6003

SUB AMBITO 01 – ALESSANDRINO ISTAT COMUNE 6003 ALESSANDRIA 6007 ALTAVILLA MONFERRATO 6013 BASSIGNANA 6015 BERGAMASCO 6019 BORGORATTO ALESSANDRINO 6021 BOSCO MARENGO 6031 CARENTINO 6037 CASAL CERMELLI 6051 CASTELLETTO MONFERRATO 6052 CASTELNUOVO BORMIDA 6054 CASTELSPINA 6061 CONZANO 6068 FELIZZANO 6071 FRASCARO 6075 FRUGAROLO 6076 FUBINE 6078 GAMALERO 6193 LU E CUCCARO MONFERRATO 6091 MASIO 6105 MONTECASTELLO 6122 OVIGLIO 6128 PECETTO DI VALENZA 6129 PIETRA MARAZZI 6141 QUARGNENTO 6142 QUATTORDIO 6145 RIVARONE 6154 SAN SALVATORE MONFERRATO 6161 SEZZADIO 6163 SOLERO 6177 VALENZA SUB AMBITO 02 – CASALESE ISTAT COMUNE 6004 ALFIANO NATTA 6011 BALZOLA 6020 BORGO SAN MARTINO 6023 BOZZOLE 6026 CAMAGNA 6027 CAMINO 6039 CASALE MONFERRATO 6050 CASTELLETTO MERLI 6056 CELLA MONTE 6057 CERESETO 6059 CERRINA MONFERRATO ISTAT COMUNE 6060 CONIOLO 6072 FRASSINELLO MONFERRATO 6073 FRASSINETO PO 6077 GABIANO 6082 GIAROLE 6094 MIRABELLO MONFERRATO 6097 MOMBELLO MONFERRATO 5069 MONCALVO 6099 MONCESTINO 6109 MORANO SUL PO 6113 MURISENGO 6115 OCCIMIANO 6116 ODALENGO GRANDE 6117 ODALENGO PICCOLO 6118 OLIVOLA 6120 OTTIGLIO 6123 OZZANO MONFERRATO 6131 POMARO MONFERRATO 6133 PONTESTURA 6135 PONZANO MONFERRATO 6149 ROSIGNANO MONFERRATO 6150 SALA MONFERRATO 6153 SAN GIORGIO MONFERRATO 6159 SERRALUNGA DI CREA 6164 SOLONGHELLO 6171 TERRUGGIA 6173 TICINETO 6175 TREVILLE 6178 VALMACCA 6179 VIGNALE MONFERRATO 6182 VILLADEATI 6184 VILLAMIROGLIO 6185 VILLANOVA MONFERRATO SUB AMBITO 03 – NOVESE TORTONESE ACQUESE E OVADESE ISTAT COMUNE 6001 ACQUI TERME 6002 ALBERA LIGURE 6005 -

Tasselli Di Cultura...Castelli, Palazzi E Dimore Storiche

AVVERTENZA Foreword Le schede dei siti e dei monumenti presenti su questa pubblicazione sono suddivise, attraverso l’utilizzo di colori diversi, per area geografica di appartenenza (zone di Acqui Terme – Ovada, Alessandria, Casale Monferrato – Valenza, Novi Ligure – Tortona); all’interno di ogni sezione gli articoli sono ordinati alfabeticamente per Comune di ubicazione dell’opera. All’interno della copertina è riportata una pratica legenda di tutti i simboli utilizzati. The pages of the sites and buildings in this publication are divided up by colour codes for each area (Acqui Terme – Ovada, Alessandria, Casale Monferrato – Valenza, Novi Ligure – Tortona); inside each section the sites are listed alphabetically according to the local town or village. On the inside cover is a key detailing all the symbols used. Recapiti Addresses Giorni e orario di apertura - Timetable; Condizioni ❼ domenica o di ingresso giorno festivo Conditions ❼ Sunday or of entrance holidays Modalità di pagamento Tickets Servizi Services COME-DOVE-QUANDO HOW-WHERE-WHEN In Piemonte, ad un’ora dedicarsi ad attività spor- In Piedmont, just an through tradition, art, di viaggio da Milano, Torino tive all’aria aperta. Autunno hour’s drive from Milan, food, wine and the spa e Genova e poco più ed inverno, invece, sono i Turin and Genoa, not far waters. Spring and distante dai confini con la mesi prediletti dai buongu- from the borders with summer Francia e la Svizzera, tra le stai che potranno assapo- France and are the Alpi ed il Mar Ligure, c’è la rare, in abbinamento ai Switzerland and best times provincia di Alessandria, pregiati vini, i prestigiosi between the Alps to che rappresenta uno dei “frutti” del territorio: tartufi, and the cuori culturali, artistici ed funghi, castagne, nocciole. -

Capitolato Appalto Linea Cuceglio

COMUNE DI SAN GIORGIO CANAVESE Provincia di Torino Tel. 0124-32.121 – Fax. 0124-32.51.06 e-mail: [email protected] – P.E.C.: [email protected] P.IVA/Cod.Fisc.: 02143040018 CAPITOLATO SPECIALE D’APPALTO PER L’AFFIDAMENTO DEL SERVIZIO TRASPORTO ALUNNI SCUOLA DELL’OBBLIGO LINEA “CUCEGLIO – MONTALENGHE” ANNO SCOLASTICO 2013/2014 ART. 1 – OGGETTO DELL’APPALTO Costituisce oggetto del presente Capitolato Speciale d’Appalto l’affidamento del servizio di trasporto a favore degli alunni della Scuola dell’obbligo provenienti dai Comuni convenzionati di CUCEGLIO e MONTALENGHE frequentanti la scuola Media “CARLO BOTTA di SAN GIORGIO CAN.SE. Il servizio sarà effettuato nei giorni dal lunedì al venerdì con le modalità e gli itinerari indicati all’art. 4 del presente capitolato. L’Amministrazione comunale si riserva la facoltà di apportare modiche ai percorsi ed al programma delle fermate anche nel corso dell’anno scolastico, concordando con la ditta le modalità di variazione. La durata temporale annuale del servizio coincide con l’anno scolastico 2013/2014. Il Servizio di cui all’oggetto è da considerarsi a tutti gli effetti servizio di pubblico interesse e per nessuna ragione potrà essere sospeso o abbandonato, pena l’immediata risoluzione del contratto e risarcimento dei danni subiti, fatti salvi i casi comprovati di forza maggiore o di scioperi del personale della ditta, ferma restando la non fatturazione del mancato servizio. ART. 2 – DURATA ED IMPORTO DELL’APPALTO Il servizio viene appaltato per l’anno scolastico 2013/2014 ed avrà durata pari a quella del calendario scolastico approvato dalle competenti autorità (Ministero della Pubblica Istruzione, Provveditorato agli Studi), in relazione ai giorni di effettiva apertura delle scuole. -

Pagina 1 Comune Sede Torino Sede Grugliasco Sede Orbassano Torino

Sede Sede Sede Comune Torino Grugliasco Orbassano Torino 21388 794 461 Moncalieri 987 51 29 Collegno 958 70 41 Numero di iscritti alle Rivoli 894 79 72 sedi UNITO di Torino, Settimo Torinese 832 22 10 Grugliasco e Nichelino 752 26 27 Orbassano distinte Chieri 713 55 14 Grugliasco 683 94 32 Venaria Reale 683 26 23 Ad es. sono 958 i Pinerolo 600 19 37 domiciliati a Collegno Chivasso 445 22 3 che sono iscritti a CdS San Mauro Torinese 432 21 7 Orbassano 404 27 31 sono 70 i domiciliati a Carmagnola 393 24 5 Collegno che sono Ivrea 381 23 1 iscritti a CdS con sede Cirié 346 14 12 Caselle Torinese 323 17 12 sono 41 i domiciliati a Rivalta di Torino 307 28 29 Collegno che sono Piossasco 292 16 25 iscritti a CdS con sede Beinasco 284 16 23 Alpignano 274 24 11 Volpiano 271 12 1 Pianezza 264 18 3 Vinovo 262 11 14 Borgaro Torinese 243 16 1 Giaveno 238 12 11 Rivarolo Canavese 232 7 Leini 225 10 4 Trofarello 224 18 5 Pino Torinese 212 8 3 Avigliana 189 14 16 Bruino 173 6 16 Gassino Torinese 173 10 1 Santena 161 13 4 Druento 159 8 6 Poirino 151 12 5 San Maurizio Canavese 151 8 7 Castiglione Torinese 149 8 2 Volvera 135 5 7 None 133 7 3 Carignano 130 4 1 Almese 124 10 4 Brandizzo 120 4 1 Baldissero Torinese 119 5 1 Nole 118 5 3 Castellamonte 116 5 Cumiana 114 6 9 La Loggia 114 7 3 Cuorgné 111 5 2 Cambiano 108 9 5 Candiolo 108 7 2 Pecetto Torinese 108 6 2 Buttigliera Alta 102 9 4 Luserna San Giovanni 101 7 8 Caluso 100 1 Pagina 1 Sede Sede Sede Comune Torino Grugliasco Orbassano Bussoleno 97 6 1 Rosta 90 12 4 San Benigno Canavese 88 2 Lanzo Torinese -

LE IMPRESE DEL DISTRETTO ORAFO VALENZANO (Valenza, San Salvatore, Bassignana, Pecetto Di Valenza) AL 3O GIUGNO 20201

1 LE IMPRESE DEL DISTRETTO ORAFO VALENZANO (Valenza, San Salvatore, Bassignana, Pecetto di Valenza) AL 3O GIUGNO 20201 Indice delle pagine: a pagina 2 l’analisi in sintesi a pagina 3 le imprese di Valenza a pagina 5 le imprese di Valenza per settore a pagina 6 le imprese di Valenza per classe di natura giuridica e per settore a pagina 9 le imprese artigiane di Valenza a pagina 12 l’export di gioielleria a pagina 15 gli altri 3 Comuni del Distretto Orafo: Bassignana, Pecetto, San Salvatore a pagina 17 il valore della produzione nel Distretto a pagina 18 le imprese del Distretto Orafo non fabbricanti a pagina 20 l’evoluzione del Distretto dal 2004 al 2020 1 Questo report è stato scritto nel mese di luglio 2020. Per il 2020 i dati sono al 30 giugno; per gli anni precedenti i dati sono al 31 dicembre di ogni anno; i dati export sono invece aggiornati al primo trimestre 2020. Si tratta degli ultimi dati disponibili al momento in cui si scrive. _______________________________________________________________________________________ Report scritto a luglio 2020 a cura dell’Ufficio Studi Camera di Commercio di Alessandria. T. 0131 313 350, [email protected] www.al.camcom.gov.it/studi 2 L’ANALISI IN SINTESI VALENZA . Sono 2.331 le imprese complessive (tutte, non solo le orafe) a Valenza al 30 giugno 2020, e occupano 6.805 addetti2 . Manifattura, commercio e costruzioni sono i primi tre settori dell’economia valenzana, per numero di imprese . Le imprese orafe3 sono 706, pari al 30% del totale imprese, e occupano 4.249 addetti.