Contestation and Service Delivery in Urban South Africa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cape Town's Film Permit Guide

Location Filming In Cape Town a film permit guide THIS CITY WORKS FOR YOU MESSAGE FROM THE MAYOR We are exceptionally proud of this, the 1st edition of The Film Permit Guide. This book provides information to filmmakers on film permitting and filming, and also acts as an information source for communities impacted by film activities in Cape Town and the Western Cape and will supply our local and international visitors and filmmakers with vital guidelines on the film industry. Cape Town’s film industry is a perfect reflection of the South African success story. We have matured into a world class, globally competitive film environment. With its rich diversity of landscapes and architecture, sublime weather conditions, world-class crews and production houses, not to mention a very hospitable exchange rate, we give you the best of, well, all worlds. ALDERMAN NOMAINDIA MFEKETO Executive Mayor City of Cape Town MESSAGE FROM ALDERMAN SITONGA The City of Cape Town recognises the valuable contribution of filming to the economic and cultural environment of Cape Town. I am therefore, upbeat about the introduction of this Film Permit Guide and the manner in which it is presented. This guide will be a vitally important communication tool to continue the positive relationship between the film industry, the community and the City of Cape Town. Through this guide, I am looking forward to seeing the strengthening of our thriving relationship with all roleplayers in the industry. ALDERMAN CLIFFORD SITONGA Mayoral Committee Member for Economic, Social Development and Tourism City of Cape Town CONTENTS C. Page 1. -

(Re) Constructing Identities: South African Domestic Workers, English Language Learning, and Power a Dissertation SUBMITTED TO

(Re) Constructing Identities: South African Domestic Workers, English Language Learning, and Power A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Anna Kaiper IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Dr. Joan DeJaeghere, Advisor May 2018 © Anna Kaiper 2018 i Acknowledgements To the women in my study: • It is because of you that this dissertation is in existence. Thank you and your families for everything you have given me and taught me. By sharing the stories of your lives, you have changed my own. To the most important people in my life: • My Mommy PP, who has provided me with the most incredible love, support, wisdom, and inspiration throughout my life. I love you forever times 2 ½ + 1. Love, Anna PB • My Daddy Bruce- although your life has been anything but easy, your incredible creativity, intelligence, and passion for life keeps me inspired every day. I love you Dad. • My love, Ian- having you as a partner makes me feel loved and thankful every single day. I couldn’t have finished this without you (and our sweet family: Thandi, Annie, and Snoopy). I love you Nini, forever. • My Best Fwend, Steph, whose incredible friendship and sisterhood has sustained me for decades and ALWAYS makes me happy. Your love for human beings motivates me daily. • Ray Ray- Your continual ability to care and love while you fight for what is right and just makes me feel proud to call you one of my best and longest friends! (and love to Errol and sweet Hazel too) To my incredible mentors: • My advisor, Dr. -

Super Family

Super Family (Chaim Freedman, Petah Tikvah, Israel, September 2008) Yehoash (Heibish/Gevush) Super, born c.1760, died before 1831 in Latvia. He married unknown. I. Shmuel Super, born 1781,1 died by 1855 in Lutzin (now Ludza), Latvia,2 occupation alcohol trader. Appears in a list from 1837 of tax litigants who were alcohol traders in Lutzin. (1) He married Brokha ?, born 1781 in Lutzin (now Ludza), Latvia,3 died before 1831 in Lutzin (now Ludza), Latvia.3 (2) He married Elka ?, born 1794.4 A. Payka Super, (daughter of Shmuel Super and Brokha ?) born 1796/1798 in Lutzin (now Ludza), Latvia,3 died 1859 in Lutzin (now Ludza), Latvia.5 She married Yaakov-Keifman (Kivka) Super, born 1798,6,3 (son of Sholom "Super" ?) died 1874 in Lutzin (now Ludza), Latvia.7 Yaakov-Keifman: Oral tradition related by his descendants claims that Koppel's surname was actually Weinstock and that he married into the Super family. The name change was claimed to have taken place to evade military service. But this story seems to be invalid as all census records for him and his sons use the name Super. 1. Moshe Super, born 1828 in Lutzin (now Ludza), Latvia.8 He married Sara Goda ?, born 1828.8 a. Bentsion Super, born 1851 in Lutzin (now Ludza), Latvia.9 He married Khana ?, born 1851.9 b. Payka Super, born 1854 in Lutzin (now Ludza), Latvia.10 c. Rassa Super, born 1857 in Lutzin (now Ludza), Latvia.11 d. Riva Super, born 1860 in Lutzin (now Ludza), Latvia.12 e. Mushke Super, born 1865 in Lutzin (now Ludza), Latvia.13 f. -

Women in the Informal Economy: the Face of Precariousness in South Africa

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Stellenbosch University SUNScholar Repository Women in the informal economy: Precarious labour in South Africa Makoma Mabilo Thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (Political Science) in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Prof. A. Gouws March 2018 The financial assistance of the National Research Foundation (NRF) towards this research is hereby acknowledged. Opinions expressed and conclusions arrived at, are those of the author and are not necessarily to be attributed to the NRF. Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Makoma Mabilo March 2018 Copyright © 2018 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved i Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Abstract High levels of unemployment, widespread poverty and growing inequality in South Africa have led to an emphasis on employment as a solution to these problems. In the current post-apartheid era, various scholars have documented a growing flexibility within South Africa’s labour market, which they suggest indicates a breakdown of traditional, formal full-time employment contracts as well as a growth of precarious, marginal and atypical employment. -

CT, Franschoek, Eastern Cape

T H E A F R I C A H U B S O U T H B Y S M A L L W O R L D M A R K E T I N G A F R I C A T r u s t e d i n s i d e r k n o w l e d g e f r o m h a n d p i c k e d e x p e r t s S A M P L E I T I N E R A R Y # 1 I N P A R T N E R S H I P W I T H N E W F R O N T I E R S T O U R S Cape Town, Franschoek "South Africa can be overwhelming to sell due & Eastern Cape Safari to the sheer variety of locations and 9 nights accommodation options. This SA information sharing partnership between SWM and New Frontiers is invaluable in helping to inform & enthuse aficionados and non-specialists alike." - Albee Yeend, Albee's Africa W W W . S M A L L W O R L D M A R K E T I N G . C O . U K / T H E A F R I C A H U B I T I N E R A R Y W H O ? O V E R V I E W Families | Couples H I G H L I G H T S 4 nights | Cape Grace Cape Grace offers an excellent location to 2 nights | Boschendal explore the city from 3 nights | Kwandwe Great Fish River Lodge Treehouse experience included in Boschendal stay Guests will spend their first 4 nights Exceptional game viewing experience in the discovering Cape Town. -

Creating More Inclusive Economies: Conceptual, Measurement And

Creating More Inclusive Economies: Conceptual, Measurement and Process Dimensions By Chris Benner Gabriela Giusta Gordon McGranahan Manuel Pastor With Bidisha Chaudhuri Ivan Turok Justin Visagie May 23, 2018 http://inclusiveeconomies.org Supported by: Acknowledgements This report was supported by the Rockefeller Foundation under a project led by PI Chris Benner at the Everett Program for Technology and Social Change, and co-PIs Manuel Pastor at the Program for Environmental and Regional Equity (PERE) and Gordon McGranahan at the Institute of Development Studies (IDS). Considerable thanks to the Rockefeller Foundation for their generous funding which made this work possible. We also like to thank the team of people at the Foundation who worked with us closely throughout the entirety of this project for their invaluable insights, support and timely feedback. We extend our gratitude to our research partners Bidisha Chaudhuri at the International Institute of Information Technology Bangalore in India, and Ivan Turok and Justin Visagie at the Human Sciences Research Council in South Africa. Additional thanks to our partner organizations in Colombia, Fundación Corona and Red de Ciudades Cómo Vamos. Special thanks to Everett Program staff and fellows, Katie Roper, Amber Holguin, Tonje Switzer, Janie Flores, Ryan Shook, Omar Paz, Tyler Spencer, Yesenia Torres and Christine Ongjoco for their invaluable assistance, as well as Madeline Wander and Pamela Stephens at PERE, and Magaly Lopez, formerly at PERE and currently at the UCLA Labor Center for contributions on initial drafts and field work. Considerable thanks to Sarah Burd-Sharps, Besiki Kutladeze, Daniel Schensul, Eva Jesperson, Michael Bamburger, Sanjay Reddy, Michelle DePass, Deepak Bhargava, Paul Rommer, Tamara Draut, John Irons, John Mollenkopf, George Sarrinikolaou, Michael Green, Nancy Birdsall, Patricia McCarney, Ravi Kanbur, Amy Glasmeier, Victor Rubin and David Madland for feedback during our first convening in New York City. -

Your Guide to Myciti

Denne West MyCiTi ROUTES Valid from 29 November 2019 - 12 january 2020 Dassenberg Dr Klinker St Denne East Afrikaner St Frans Rd Lord Caledon Trunk routes Main Rd 234 Goedverwacht T01 Dunoon – Table View – Civic Centre – Waterfront Sand St Gousblom Ave T02 Atlantis – Table View – Civic Centre Enon St Enon St Enon Paradise Goedverwacht 246 Crown Main Rd T03 Atlantis – Melkbosstrand – Table View – Century City Palm Ln Paradise Ln Johannes Frans WEEKEND/PUBLIC HOLIDAY SERVICE PM Louw T04 Dunoon – Omuramba – Century City 7 DECEMBER 2019 – 5 JANUARY 2020 MAMRE Poeit Rd (EXCEPT CHRISTMAS DAY) 234 246 Silverstream A01 Airport – Civic Centre Silwerstroomstrand Silverstream Rd 247 PELLA N Silwerstroom Gate Mamre Rd Direct routes YOUR GUIDE TO MYCITI Pella North Dassenberg Dr 235 235 Pella Central * D01 Khayelitsha East – Civic Centre Pella Rd Pella South West Coast Rd * D02 Khayelitsha West – Civic Centre R307 Mauritius Atlantis Cemetery R27 Lisboa * D03 Mitchells Plain East – Civic Centre MyCiTi is Cape Town’s safe, reliable, convenient bus system. Tsitsikamma Brenton Knysna 233 Magnet 236 Kehrweider * D04 Kapteinsklip – Mitchells Plain Town Centre – Civic Centre 245 Insiswa Hermes Sparrebos Newlands D05 Dunoon – Parklands – Table View – Civic Centre – Waterfront SAXONSEAGoede Hoop Saxonsea Deerlodge Montezuma Buses operate up to 18 hours a day. You need a myconnect card, Clinic Montreal Dr Kolgha 245 246 D08 Dunoon – Montague Gardens – Century City Montreal Lagan SHERWOOD Grosvenor Clearwater Malvern Castlehill Valleyfield Fernande North Brutus -

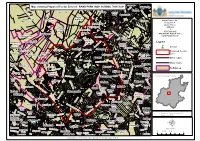

Map Showing Proposed Feeder Zone Of

n Nooitgedacht Bloubosrand e Fourways Kya Sand SP p D p o MapA sHhowing Proposed Feeder Zone of : RAND PARK HIGo H SCJHohOanOneLsb 7ur0g0151241 lie Magaliessig tk u s B i North g e Hoogland l L W e W a y s Norscot i e ll r Cosmo City ia s Noordhang Jukskei m N a n i N a r Park u Douglasdale i d a c é o M North l Rietfontein AH Sonnedal AH Riding AH Bryanston District Name: JN Circuit No: 4 North Riding G ro Cluster No: 2 sv Bellairs Park en Jackal or Address: Creek Golf Northworld AH d 1 J n a a Estate Olivedale c l ASSGAAI AVE a r n r o Northgate a e t n b s RANDPARK RIDGE EXT1 Zandspruit SP da n m a u y Rietfontein AH r RANDPARK RIDGE Sharonlea C s B n y Vandia i a H a o Sundowner Hunters K Grove m M e e Zonnehoewe AH Hill A. h s Roodekrans Ext c t Legend u e H. SP o Beverley a AH F d Country s. e Gardens er r Life Ruimsig Noord et P School P Bryanbrink Park Sundowner Northworld Sonneglans Tres Jolie AH Laser Park t Kensington B Proposed Feeder r ord E Alsef AH a xf t Ruimsig w O o Zone Ruimsig AH .S Strijdompark n Lyme Park .R Ambot AH C Bond Bromhof H New Brighton a Other roads n s Boskruin Eagle Canyon s Schoeman S Han t Hill Ferndale Kimbult AH r ij Major roads Poortview t d Hurlingham e ut o Willowbrook ho m AH W r d Bordeaux e Harveston AH st Malanshof r e Y e r d o Willowild Subplaces uge R Kr Randpark ep w ul n ub Pa lic r a s e a Ridge Ruiterhof h i R V c t a Amorosa Aanwins AH i ic b N r Honeydew s ie k i i Glenadrienne SP1 e r r d e Ridge h President d i Jo Moret n Craighall Locality in Gauteng Province C hn Vors Fontainebleau D ter Ridge e H J Wilro Wilgeheuwel a J n Radiokop . -

COPYRIGHT and CITATION CONSIDERATIONS for THIS THESIS/ DISSERTATION O Attribution — You Must Give Appropriate Credit, Provide

COPYRIGHT AND CITATION CONSIDERATIONS FOR THIS THESIS/ DISSERTATION o Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use. o NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes. o ShareAlike — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you must distribute your contributions under the same license as the original. How to cite this thesis Surname, Initial(s). (2012) Title of the thesis or dissertation. PhD. (Chemistry)/ M.Sc. (Physics)/ M.A. (Philosophy)/M.Com. (Finance) etc. [Unpublished]: University of Johannesburg. Retrieved from: https://ujcontent.uj.ac.za/vital/access/manager/Index?site_name=Research%20Output (Accessed: Date). Forsaken Heritage: The Case of Kliptown Genevieve Nicole Ray School of Tourism and Hospitality, College of Business and Economics, University of Johannesburg Supervisor: Professor C.M. Rogerson A Dissertation submitted to the College of Business and Economics, University of Johannesburg, in fulfilment for the requirement of the degree of Master in Tourism and Hospitality Submitted: August 2018 i Declaration I declare that this thesis is my own and original work, conducted under the supervision of Professor Christian Rogerson. It is submitted in fulfilment for the requirement of a master’s degree in Tourism and Hospitality in the College of Business and Economics at the University of Johannesburg, Gauteng, South Africa. No part of this research has been submitted in the past, or is being submitted, for a degree or examination at any other university. -

Advancing Transformative Justice? a Case Study of a Trade Union, Social Movement and NGO Network in South Africa

Advancing transformative justice? A case study of a trade union, social movement and NGO network in South Africa Matthew Hamilton Evans PhD University of York Politics October 2013 Abstract Transitional justice mechanisms have largely focused upon individual violations of a narrow set of civil and political rights and the provision of legal and quasi-legal remedies, typically truth commissions, amnesties and prosecutions. In contrast, this thesis highlights the significance of structural violence in producing and reproducing violations of socio-economic rights. The thesis argues that there is a need to utilise a different toolkit, and a different understanding of human rights, to that typically employed in transitional justice in order to remedy structural violations of human rights such as these. A critique of the scope of existing models of transitional justice is put forward and the thesis sets out a definition of transformative justice as expanding upon and providing an alternative to the transitional justice mechanisms typically employed in post-conflict and post-authoritarian contexts. Focusing on a case study of a network of social movements, nongovernmental organisations and trade unions working on land and housing rights in South Africa, the thesis asks whether networks of this kind can advance transformative justice. In answering this question the thesis draws upon the idea of political responsibility as a means of analysing and assessing network action. The existing literature on political responsibilities and transnational advocacy networks is interrogated and adapted to the largely domestic case study network. Based on empirical research on the case study network and an analysis of its political responsibilities the thesis finds that networks of this kind can contribute to transformative justice. -

South Africa Political Snapshot New ANC President Ramaphosa’S Mixed Hand Holds Promise for South Africa’S Future

South Africa Political Snapshot New ANC President Ramaphosa’s mixed hand holds promise for South Africa’s future South Africa’s ruling party, the African National Congress, yesterday (20 December) concluded its 54th National Conference at which it elected a new leadership. South African Deputy President Cyril Ramaphosa was announced the ANC’s new leader against a backdrop of fast-deteriorating investor confidence in the country. The new team will likely direct the ANC’s leadership of the country for the next five years and beyond. Mr Ramaphosa’s victory is not complete. The election results have been the closest they have been of any ANC leadership election in recent times. The results for the top six leaders of the ANC (Deputy President, National Chairperson, Secretary-General, Treasurer-General and Deputy Secretary-General) and the 80-member National Executive Committee (NEC - the highest decision-making body of the party between conferences) also represent a near 50-50 composition of the two main factions of the ANC. Jacob Zuma, Mr Ramaphosa’s predecessor, still retains the presidency of South Africa’s government (the next general election is still 18 months away). It enables Mr Zuma to state positions difficult for the new ANC leadership to find clawback on, and to leverage whatever is left of his expanded patronage network where it remains in place. A pointed reminder of this was delivered on the morning the ANC National Conference commenced, when President Zuma committed the government to provide free tertiary education for students from homes with combined incomes of below R600 000 – an commitment termed unaffordable by an expansive judicial investigation, designed to delay his removal from office and to paint him as a victim in the event it may be attempted. -

ANNUAL REPORT APRIL 2013–MARCH 2014 Vision: the Creation of Sustainable Human Settlements Through Development Processes Which Enable Human Rights, Dignity and Equity

ANNUAL REPORT APRIL 2013–MARCH 2014 Vision: The creation of sustainable human settlements through development processes which enable human rights, dignity and equity. Mission: To create, implement and support opportunities for community-centred settlement development and to advocate for and foster a pro-poor policy environment which addresses economic, social and spatial imbalances. Umzomhle (Nyanga), Mncediisi Masakhane, RR Section, Participatory Action Planning CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS ANC African National Congress KCT Khayelitsha Community Trust BESG Built Environment Support Group KDF Khayelitsha Development Forum Abbreviations 2 BfW Brot für die Welt KHP Khayelitsha Housing Project CBO Community-Based Organisation KHSF Khayelitsha Human Settlements Our team 3 CLP Community Leadership Programme Forum Board of Directors 4 CoCT City of Cape Town (Metropolitan) LED Local economic development Chairperson’s report 5 CORC Community Organisation Resource LRC Legal Resources Centre Centre MIT Massachusetts Institute of Executive Director’s report 6 CBP Capacity-Building Programme Technology From vision to strategy 9 CPUT Cape Peninsula University of NDHS National Department of Human Technology Settlements Affordable housing and human settlements 15 CSO Civil Society Organisation NGO Non-Governmental Organisation Building capacity in the urban sector 20 CTP Cape Town Partnership NDP National Development Plan Partnerships 23 DA Democratic Alliance NUSP National Upgrading Support DAG Development Action Group Programme Institutional change 25 DPU