From Gqogqora to Liberation: the Struggle Was My Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WITHOUT FEAR OR FAVOUR the Scorpions and the Politics of Justice

WITHOUT FEAR OR FAVOUR The Scorpions and the politics of justice David Bruce Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation [email protected] In May 2008 legislation was tabled in Parliament providing for the dissolution of the Directorate of Special Operations (known as the ‘Scorpions’), an investigative unit based in the National Prosecuting Authority. The draft legislation provides that Scorpions members will selectively be incorporated into a new investigative unit located within the SAPS. These developments followed a resolution passed at the African National Congress National Conference in Polokwane in December 2007, calling for the unit to be disbanded. Since December the ANC has been forced to defend its decision in the face of widespread support for the Scorpions. One of the accusations made by the ANC was that the Scorpions were involved in politically motivated targeting of ANC members. This article examines the issue of political manipulation of criminal investigations and argues that doing away with the Scorpions will in fact increase the potential for such manipulation thereby undermining the principle of equality before the law. he origins of current initiatives to do away Accordingly we have decided not to with the Scorpions go back several years. In prosecute the deputy president (Mail and T2001 the National Prosecuting Authority Guardian online 2003). (NPA) approved an investigation into allegations of corruption in the awarding of arms deal contracts. Political commentator, Aubrey Matshiqi has argued In October 2002 they announced that this probe that this statement by Ngcuka ‘has in some ways would be extended to include allegations of bribery overshadowed every action taken in relation to against Jacob Zuma, then South Africa’s deputy Zuma by the NPA since that point.’ Until June president. -

An Initial Archaeological Assessment of Bloubergstrand

AN INITIAL ARCHAEOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT OF BLOUBERGSTRAND (FOR STRUCTURE PLAN PURPOSES ONLY) Prepared for Steyn Larsen and Partners December 1992 Prepared by Archaeology Contracts Office Department of Archaeology University of Cape Town Rondebosch 7700 Phone (021) 650 2357 Fax (021) 650 2352 1. INTRODUCTION The purpose of this report has been to identify areas of archaeological sensitivity in an area of Bloubergstrand as part of a local structure plan being compiled by Steyn, Larsen and Partners, Town and Regional Planners on behalf of the Western Cape Regional Services Council. The area of land which is examined is presented in Figure 1. Our brief specifically requested that we not undertake any detailed site identification. The conclusions reached are the result of an in loco inspection of the area and reference to observations compiled by members of the Archaeological Field Club1 during a visit to the area in 1978. While these records are useful they are not comprehensive and inaccuracies may be present. 2. BACKGROUND Human occupation of the coast and exploitation of marine resources was practised for many thousands of years before the colonisation of southern Africa by Europeans. This practise continued for some time after colonisation as well. Archaeological sites along the coast are often identified by the scatters of marine shells (middens) which accumulated at various places, sometimes in caves and rockshelters, but very often out in the open. Other food remains such as bones from a variety of faunas will often accompany the shells showing that the early inhabitants utilised the full range of resources of the coastal zone. -

SAHRA-Annual-Report-2007.Pdf

SAHRA Ann Rep Cover 2007 repro Monday, August 27, 2007 1:21:22 PM Table of Contents SAHRA’S VISION AND MISSION STATEMENT 2 LETTER FROM THE CHAIRPERSON 3 THE CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER’S FOREWORD AND MESSAGE 4 APPLICABLE ACTS AND OTHER INFORMATION 7 STATEMENT OF RESPONSIBILITY 8 CORPORATE AFFAIRS 9 Human Resources Management 10 Information and Auxiliary Services 25 HERITAGE RESOURCES MANAGEMENT 27 Head Office Units Archaeology, Palaeontology and Meteorites Unit 28 Architectural Heritage Landscape Unit 34 Burial Grounds and Graves Unit 38 Grading and Declarations Unit 44 Heritage Objects Unit 48 Living Heritage Unit 54 Maritime Archaeology Unit 62 National Inventory Unit 72 Provincial Offices Eastern Cape 76 Free State 80 Gauteng 80 Kwa-Zulu Natal 92 Limpopo 94 Mpumalanga 98 North West 102 Northern Cape 110 Western Cape 116 LEGAL UNIT 128 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 131 SAHRA OFFICES AND STAFF 161 SAHRA’S VISION SAHRA’s vision is to provide for the identification, conservation, protection and promotion of our heritage resources for present and future generations. SAHRA’S MISSION As custodians of our national estate our mission is: ° to coordinate and monitor the identification of our national heritage resources; ° to set norms and standards and maintain the management of heritage resources nationally; ° to encourage co-operative conservation of our national estate; ° to enable and facilitate the development of provincial structures; ° to control the export and import of nationally significant heritage resources; ° to develop policy initiative for the promotion and management of our heritage; ° to nurture an holistic celebration of our history; ° to set national policy for heritage resources management, i.e. -

Refashioning Provincial Government in Democratic South Africa, 1994-1996

REFASHIONING PROVINCIAL GOVERNMENT IN DEMOCRATIC SOUTH AFRICA, 1994-1996 SYNOPSIS In 1994, nine provincial heads, or premiers, came to power as a result of South Africa’s first democratic elections. Many had spent decades mobilizing opposition to the state but had never held political office. All faced the challenge of setting up provincial administrations under a new constitution that reduced the number of provinces and cut the number of departments in each administration, eliminating significant numbers of staff. Anticipating those challenges, the political parties that negotiated South Africa’s democratic transition had laid the groundwork for a commission that would help the newly elected provincial leaders set up their administrations. The panel, called the Commission on Provincial Government, operated under a two-year mandate and played an important role in advising the premiers and mediating between the provincial governments and other influential groups. By providing a trusted channel of critical information, the commission helped the new provincial leaders find their feet after their election, reducing tensions and keeping the postelectoral peace. Tumi Makgetla and Rachel Jackson drafted this case study based on interviews conducted by Makgetla in Pretorian and Johannesburg, South Africa, in January and February 2010. A separate policy note, “Negotiating Divisions in a Divided Land: Creating Provinces for a New South Africa, 1993,” focuses on provincial boundary delimitation. Case originally published in April 2011. Case revised and republished in August 2013. INTRODUCTION that we need to do away with the duplication of “Jobs, jobs, jobs!” read election posters for the some of the posts. We had to cut the civil service African National Congress (ANC) in the run-up almost by half in certain areas,” he said. -

A Comparative Study of Zimbabwe and South Africa

FACEBOOK, YOUTH AND POLITICAL ACTION: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF ZIMBABWE AND SOUTH AFRICA A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY of SCHOOL OF JOURNALISM AND MEDIA STUDIES, RHODES UNIVERSITY by Admire Mare September 2015 ABSTRACT This comparative multi-sited study examines how, why and when politically engaged youths in distinctive national and social movement contexts use Facebook to facilitate political activism. As part of the research objectives, this study is concerned with investigating how and why youth activists in Zimbabwe and South Africa use the popular corporate social network site for political purposes. The study explores the discursive interactions and micro- politics of participation which plays out on selected Facebook groups and pages. It also examines the extent to which the selected Facebook pages and groups can be considered as alternative spaces for political activism. It also documents and analyses the various kinds of political discourses (described here as digital hidden transcripts) which are circulated by Zimbabwean and South African youth activists on Facebook fan pages and groups. Methodologically, this study adopts a predominantly qualitative research design although it also draws on quantitative data in terms of levels of interaction on Facebook groups and pages. Consequently, this study engages in data triangulation which allows me to make sense of how and why politically engaged youths from a range of six social movements in Zimbabwe and South Africa use Facebook for political action. In terms of data collection techniques, the study deploys social media ethnography (online participant observation), qualitative content analysis and in-depth interviews. -

Final Belcom Agenda 18 April 2012

MEETING OF HERITAGE WESTERN CAPE BELCOM 18 APRIL 2012, IN THE 1st FLOOR BOARDROOM, PROTEA ASSURANCE BUILDING, GREENMARKERT SQUARE, CAPE TOWN AT 08H00 PLEASE NOTE THAT: LUNCH TIME WILL START AT 12H30 UNTIL 14H30 DUE TO UNVEILING OF HWC BADGES Case Item Case No Subject Documents to be tabled Matter Reference Officer Documents sent to Notes 1 Opening 2 Attendance 3 Apologies 4 Approval of the previous minutes 4.1 Meeting held on 22 March 2012 4.2 Meeting held on 30 March 2012 5 Confidential Matters 6 Administration Matters Outcome of the Appeals and Tribunal AH/CvW 6.1 Committees ZS 6.2 Erf 443, 47 Napier Street, De Waterkant 7 Appointments None 7.1 MATTERS TO BE DISCUSSED FIRST SESSION: TEAM WEST PRESENTATION W.8 PROVINCIAL HERITAGE SITE: SECTION 27 PERMIT APPLICATIONS Proposed Re-Assembly of the Cenotaph on A Heritage Statement prepared by Bridget Matter W.8.1 HM/CAPE TOWN/GRAND PARADE JW the Grand Parade, Darling Street, Cape Town O'Donoghue, dated April 2012 to be tabled. Arising Site Inspection Report prepared by Mr Chris W.8.2 Proposed Routine Road and Stone Retaining Wall Maintanance, Swartberg Pass, Main Snelling to be tabled Matter HM/CANGO CAVES TO PRINCE Road 369, from Cango caves to Prince Albert Arising ALBERT RN X1110601TG0 Proposed Alterations and Additions, South Matter W.8.3 Re-Submission to be tabled HM/NEWLANDS/ERF 96660 TG 3 African Breweries, Erf 96660, Newlands Arising BELCom Agenda 18 April 2012 Page 1 HM/TULBAGH/SCHOONDERZICHT W.8.4 TG SW, MA and RJ Proposed Alterations and Additions, Farm A Heritage Statement prepared -

Download This Report

Military bases and camps of the liberation movement, 1961- 1990 Report Gregory F. Houston Democracy, Governance, and Service Delivery (DGSD) Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC) 1 August 2013 Military bases and camps of the liberation movements, 1961-1990 PREPARED FOR AMATHOLE DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY: FUNDED BY: NATIONAL HERITAGE COUNCI Table of Contents Acronyms and Abbreviations ..................................................................................................... ii Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................... iii Chapter 1: Introduction ...............................................................................................................1 Chapter 2: Literature review ........................................................................................................4 Chapter 3: ANC and PAC internal camps/bases, 1960-1963 ........................................................7 Chapter 4: Freedom routes during the 1960s.............................................................................. 12 Chapter 5: ANC and PAC camps and training abroad in the 1960s ............................................ 21 Chapter 6: Freedom routes during the 1970s and 1980s ............................................................. 45 Chapter 7: ANC and PAC camps and training abroad in the 1970s and 1980s ........................... 57 Chapter 8: The ANC’s prison camps ........................................................................................ -

Undamaged Reputations?

UNDAMAGED REPUTATIONS? Implications for the South African criminal justice system of the allegations against and prosecution of Jacob Zuma AUBREY MATSHIQI CSVRCSVR The Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation CENTRE FOR THE STUDY OF VIOLENCE AND RECONCILIATION Criminal Justice Programme October 2007 UNDAMAGED REPUTATIONS? Implications for the South African criminal justice system of the allegations against and prosecution of Jacob Zuma AUBREY MATSHIQI CSVRCSVR The Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation Supported by Irish Aid ABOUT THE AUTHOR Aubrey Matshiqi is an independent researcher and currently a research associate at the Centre for Policy Studies. Published by the Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation For information contact: Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation 4th Floor, Braamfontein Centre 23 Jorissen Street, Braamfontein PO Box 30778, Braamfontein, 2017 Tel: +27 (11) 403-5650 Fax: +27 (11) 339-6785 http://www.csvr.org.za © 2007 Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation. All rights reserved. Design and layout: Lomin Saayman CONTENTS Acknowledgements 4 1. Introduction 5 2. The nature of the conflict in the ANC and the tripartite alliance 6 3. The media as a role-player in the crisis 8 4. The Zuma saga and the criminal justice system 10 4.1 The NPA and Ngcuka’s prima facie evidence statement 10 4.2 The judiciary and the Shaik judgment 11 5. The Constitution and the rule of law 12 6. Transformation of the judiciary 14 7. The appointment of judges 15 8. The right to a fair trial 17 9. Public confidence in the criminal justice system 18 10. -

Women in Twentieth Century South African Politics

WOMEN IN TWENTIETH CENTURY SOUTH AFRICAN POLITICS: WOMEN IN TWENTIETH CENTURY SOUTH AFRICAN POLITICS: THE FEDERATION OF SOUTH AFRICAN WOMEN, ITS ROOTS, GROWTH AND DECLINE A thesis submitted for the Degree of Master of Arts at the University of Cape Town October 1978 C.J. WALKER ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express my appreciation to my supervisor, Robin Hallett, and to those friends who helped and encouraged me in numerous different ways. I also wish to acknowledge the financial assistance I received from the following sources, which made the writing of this thesis possible: Human Sciences Research Council Harry Crossley Scholarship Fund H.B. Webb Gijt. Scholarship Fund University of Cape Town Council. The views expressed in this thesis are those of the author alone. CONTENTS List of Abbreviations used in text Introduction CHAPTER 1 : The Position of Women, 1921-1954 CHAPTER 2 : The Roots of the FSAW, 1910-1939 CHAPTER 3 : The Roots of the FSAW, 1939-1954 CHAPTER 4 : The Establishment of the FSAW CHAPTER 5 : The Federation of South African Women, 1954-1963 CHAPTER 6 : The FSAW, 1954-1963: Structure and Strategy CHAPTER 7 : Relationships with the Congress Alliance: The Women's Movement and National Liberation CHAPTER 8 : Conclusion APPENDICES BIBI,!OGRAPHY iv V 1 53 101 165 200 269 320 343 349 354 ABBREVIATIONS USED IN TEXT AAC AllAfricanConvention AME American Methodist Episcopal (Church) ANC African National Congress ANCWL African National Congress Women's League APO African People's Organisation COD CongressofDemocrats CPSA Communist Party -

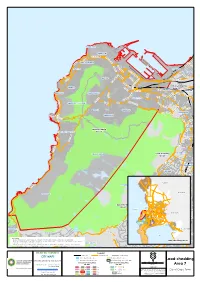

Load-Shedding Area 7

MOUILLE POINT GREEN POINT H N ELEN SUZMA H EL EN IN A SU M Z M A H N C THREE ANCHOR BAY E S A N E E I C B R TIO H A N S E M O L E M N E S SEA POINT R U S Z FORESHORE E M N T A N EL SO N PAARDEN EILAND M PA A A B N R N R D D S T I E E U H E LA N D R B H AN F C EE EIL A K ER T BO-KAAP R T D EN G ZO R G N G A KLERK E E N FW DE R IT R U A B S B TR A N N A D IA T ST S R I AN Load-shedding D D R FRESNAYE A H R EKKER L C Area 15 TR IN A OR G LBERT WOODSTOCK VO SIR LOWRY SALT RIVER O T R A N R LB BANTRY BAY A E TAMBOERSKLOOF E R A E T L V D N I R V R N I U M N CT LT AL A O R G E R A TA T E I E A S H E S ARL K S A R M E LIE DISTRICT SIX N IL F E V V O D I C O T L C N K A MIL PHILIP E O M L KG L SIGNAL HILL / LIONS HEAD P O SO R SAN I A A N M A ND G EL N ON A I ILT N N M TIO W STA O GARDENS VREDEHOEK R B PHILI P KGOSA OBSERVATORY NA F P O H CLIFTON O ORANJEZICHT IL L IP K K SANA R K LO GO E O SE F T W T L O E S L R ER S TL SET MOWBRAY ES D Load-shedding O RH CAMPS BAY / BAKOVEN Area 7 Y A ROSEBANK B L I S N WOO K P LSACK M A C S E D O RH A I R O T C I V RONDEBOSCH TABLE MOUNTAIN Load-shedding Area 5 KLIP PER N IO N S U D N A L RONDEBOSCH W E N D N U O R M G NEWLANDS IL L P M M A A A C R I Y N M L PA A R A P AD TE IS O E R P R I F 14 Swartland RIA O WYNBERG NU T C S I E V D CLAREMONT O H R D WOO BOW Drakenstein E OUDEKRAAL 14 D IN B U R G BISHOPSCOURT H RH T OD E ES N N A N Load-shedding 6 T KENILWORTH Area 11 Table Bay Atlantic 2 13 10 T Ocean R 1 O V 15 A Stellenbosch 7 9 T O 12 L 5 22 A WETTO W W N I 21 L 2S 3 A I A 11 M T E O R S L E N O D Hout Bay 16 4 O V 17 O A H 17 N I R N 17 A D 3 CONSTANTIA M E WYNBERG V R I S C LLANDUDNO T Theewaterskloof T E O 8 L Gordon's R CO L I N L A STA NT Bay I HOUT BAY IA H N ROCKLEY False E M H Bay P A L A I N MAI N IA Please Note: T IN N A G - Every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of information in this map at the time of puMblication . -

Greater Cape Metro Regional Spatial Implementation Framework Final Report July 2019

Greater Cape Metro Regional Spatial Implementation Framework Final Report July 2019 FOREWORD The Western Cape Government will advance the spatial transformation of our region competitive advantages (essentially tourism, food and calls on us all to give effect to a towards greater resilience and spatial justice. beverages, and education) while anticipating impacts of technological innovation, climate change and spatial transformation agenda The Department was challenged to explore the urbanization. Time will reveal the extent to which the which brings us closer to the linkages between planning and implementation dynamic milieu of demographic change, IT advances, imperatives of growing and and to develop a Greater Cape Metropolitan the possibility of autonomous electric vehicles and sharing economic opportunities Regional Implementation Framework (GCM RSIF) climate change (to name a few) will affect urban and wherever we are able to impact rather than “just another plan” which will gravitate to regional morphology. The dynamic environment we upon levers of change. Against the bookshelf and not act as a real catalyst for the find ourselves in is underscored by numerous potential the background of changed implementation of a regional logic. planning legislation, and greater unanticipated impacts. Even as I pen this preface, clarity regarding the mandates of agencies of This GCM RSIF is the first regional plan to be approved there are significant issues just beyond the horizon governance operating at different scales, the PSDF in terms of the Western Cape Land Use Planning Act, for this Province which include scientific advances in 2014 remained a consistent guide and mainspring, 2014. As such it offered the drafters an opportunity (a AI, alternative fuel types for transportation (electric prompting us to give urgent attention to planning in kind of “laboratory”) to test processes and procedures vehicles and hydrogen power) and the possibility the Greater Cape Metropolitan Region as one of three in the legislation. -

Activism in Manenberg, 1980 to 2010

Then and Now: Activism in Manenberg, 1980 to 2010 Julian A Jacobs (8805469) University of the Western Cape Supervisor: Prof Uma Dhupelia-Mesthrie Masters Research Essay in partial fulfillment of Masters of Arts Degree in History November 2010 DECLARATION I declare that „Then and Now: Activism in Manenberg, 1980 to 2010‟ is my own work and that all the sources I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by means of complete references. …………………………………… Julian Anthony Jacobs i ABSTRACT This is a study of activists from Manenberg, a township on the Cape Flats, Cape Town, South Africa and how they went about bringing change. It seeks to answer the question, how has activism changed in post-apartheid Manenberg as compared to the 1980s? The study analysed the politics of resistance in Manenberg placing it within the over arching mass defiance campaign in Greater Cape Town at the time and comparing the strategies used to mobilize residents in Manenberg in the 1980s to strategies used in the period of the 2000s. The thesis also focused on several key figures in Manenberg with a view to understanding what local conditions inspired them to activism. The use of biographies brought about a synoptic view into activists lives, their living conditions, their experiences of the apartheid regime, their brutal experience of apartheid and their resistance and strength against a system that was prepared to keep people on the outside. This study found that local living conditions motivated activism and became grounds for mobilising residents to make Manenberg a site of resistance. It was easy to mobilise residents on issues around rent increases, lack of resources, infrastructure and proper housing.