The Press and Edward Kennedy: a Case Study of Journalistic Behavior

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ORANGE COUNTY CAUFORNIA Continued on Page 53

KENNEDY KLUES Research Bulletin VOLUME II NUMBER 2 & 3 · November 1976 & February 1977 Published by:. Mrs • Betty L. Pennington 6059 Emery Street Riverside, California 92509 i . SUBSCRIPTION RATE: $6. oo per year (4 issues) Yearly Index Inc~uded $1. 75 Sample copy or back issues. All subscriptions begin with current issue. · $7. 50 per year (4 issues) outside Continental · · United States . Published: · August - November - Febr:UarY . - May .· QUERIES: FREE to subscribers, no restrictions as· ·to length or number. Non subscribers may send queries at the rate of 10¢ pe~)ine, .. excluding name and address. EDITORIAL POLICY: -The E.ditor does· not assume.. a~y responsibility ~or error .. of fact bR opinion expressed by the. contributors. It is our desire . and intent to publish only reliable genealogical sour~e material which relate to the name of KENNEDY, including var.iants! KENEDY, KENNADY I KENNEDAY·, KENNADAY I CANADA, .CANADAY' · CANADY,· CANNADA and any other variants of the surname. WHEN YOU MOVE: Let me know your new address as soon as possibie. Due. to high postal rates, THIS IS A MUST I KENNEDY KLyES returned to me, will not be forwarded until a 50¢ service charge has been paid, . coi~ or stamps. BOOK REVIEWS: Any biographical, genealogical or historical book or quarterly (need not be KENNEDY material) DONATED to KENNEDY KLUES will be reviewed in the surname· bulletins·, FISHER FACTS, KE NNEDY KLUES and SMITH SAGAS • . Such donations should be marked SAMfLE REVIEW COPY. This is a form of free 'advertising for the authors/ compilers of such ' publications~ . CONTRIBUTIONS:· Anyone who has material on any KE NNEDY anywhere, anytime, is invited to contribute the material to our putilication. -

Senator Edward

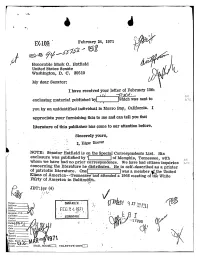

_ _ 7 _g__ ! 1 i 3 4 February24¢, 1971 'REG-#7-l5 7% HonorableC!. Mark Hateld W » United. States Senate Washington, D. C, 20510 M; My dear -Senator; » i I have receivedyogr letter of gebrllti1351 F be enclosingp11b1ished'by material to s* sent_ Ib"/C yon.by an unidentified inélividualin Morro;Bay,; ¬&.1if011I.119i-I appreciate your"furnishing thisto me.and0an1te11Y°u'th9~l? literatureof this publisher has come.to our attention before. , Sincerely you1$, i s ~ J, EdgaliHoover NOTE: SenatorHatfield ison the Specia17Cor_respo,n_dents-His List.' enclosure waspI1b1iSheClby !|:| of Memphis, Tennessee, with 106 V5-fh0m»have We had'no_ *corresponden prior _:~e.have We had oitizeninquiries ibvc cvonceroningthe" literaturehe distributes. He is self-described asai printer of patrioticliterature. Qne was membergj;a the United K;{§~nSAmerica--Tenne_ssee"and of attendeda 1966meeting oftiiaetWhite t Party of America in Baltimeie-. /it ' 92 Tolson __.______ JBT:.jsr ! . I P» " Sullivan ,>.¬_l."/ Zllohr a l 4 Bisl92op.___.ri Brennan. C.D. Callahan i_.. CaSPCT i__.____ Conrad .?__._____ ~ 1* t : *1 l ~ nalb<§y§f_,Iz__t'_I_t ,coMMFBI, 8T~2, it __~ _ at Felt " l , ......W_-»_-_-»_Qtg/<>i.l£Fa¥, .,¢ Gale Roseni___ Tavel _i___r Walters ____i__ Soyars ' Tole. Ronni l set 97l Holmes _ _ M Si andv ¬ * MAI_L~R0.01§/ll:_ TELETYPE UNII[:] 3* .7H, §M1'. 'Icls'>n.-_._.__ -K i»><':uRyM. JACKSON,WASH., CHAIRMAN~92 Q "1 MT Sullivan? c|_|rrro|'uANDERSON, P.Mac. N. sermon m_|_o 'v_o. -

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (2)” of the Sheila Weidenfeld Files at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 14, folder “5/12/75 - Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (2)” of the Sheila Weidenfeld Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Gerald Ford donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Some items in this folder were not digitized because it contains copyrighted materials. Please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library for access to these materials. Digitized from Box 14 of the Sheila Weidenfeld Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library Vol. 21 Feb.-March 1975 PUBLISHED BI-MONTHLY BY PARC, THE PHILADELPHIA ASSOCIATION FOR RETARDED CITIZENS FIRST LADY TO BE HONORED Mrs. Gerald R. Ford will be citizens are invited to attend the "guest of honor at PARC's Silver dinner. The cost of attending is Anniversary Dinner to be held at $25 per person. More details the Bellevue Stratford Hotel, about making reservations may be Monday, May 12. She will be the obtained by calling Mrs. Eleanor recipient of " The PARC Marritz at PARC's office, LO. -

VINCENT VALDEZ the Strangest Fruit

VINCENT VALDEZ The Strangest Fruit Staniar Gallery Washington and Lee University April 27–May 29, 2015 The Strangest Fruit Vincent Valdez Staniar Gallery Department of Art and Art History Washington and Lee University 204 West Washington Street Lexington, VA 24450 USA http://www.wlu.edu/staniar-gallery The Staniar Gallery endeavors to respect copyright in a manner consistent with its nonprofit educational mission. If you believe any material has been included in this publication improperly, please contact the Staniar Gallery. Copyright © 2015 by Staniar Gallery, Washington and Lee University, Lexington, Virginia All essays copyright © 2015 by the authors All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Layout by Billy Chase Editing in English by Kara Pickman Editing of Spanish translations by María Eugenia Hidalgo Preliminary Spanish translations by Mariana Aguirre, Mauricio Bustamante, Sally Curtiss, Franco Forgiarini, Ellen Mayock, Alicia Martínez, Luna Rodríguez, and Daniel Rodríguez Segura Printed and bound in Waynesboro, Virginia, by McClung Companies English and Spanish covers: Vincent Valdez, Untitled, from The Strangest Fruit (2013). Oil on canvas, 92 x 55 inches. © 2015 Vincent Valdez. Photo: Mark Menjivar MUDD CENTER EFGFoundation for ETHICS This catalogue has been funded in part by the Elizabeth Firestone Graham Foundation, the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities and Washington and Lee’s Roger Mudd Center for Ethics. The Strangest Fruit Vincent Valdez April 27–May 29, 2015 Staniar Gallery Washington and Lee University Lexington, Virginia Catalogue Contributors: Clover Archer Lyle William D. -

We Are All Called to Be Doormen Faith 3

NowadaysMontgomery Catholic Preparatory School Fall 2015 • Vol 4 • Issue 1 Administration 2 We are All Called to be Doormen Faith 3 Perhaps Saint André Bessette countless achievements of the School News 6 should be named the Patron saint students of Montgomery Catholic Student Achievement 9 for this issue of Nowadays. Preparatory School in many areas: academic, the arts, athletics, and Alumni 14 St. André was orphaned at a service. These accomplishments very early age, lived a life of Faculty News 17 are due to the students’ extreme poverty, and had little dedication and hard work, but Memorials 18 opportunity to go to school. also to their parents’ support and He would be termed illiterate Advancement 20 teacher involvement. They are in today’s standards because the doormen helping to open the he was barely able to write his doors of possibilities. name. He was short in stature and struggled with health issues. You will also read about the many Planning process has been on However, this did not deter him donors that have supported going for the past 10 months, and from his desire to become a MCPS through their gifts of time, on June 18 over 100 stakeholders, member of the Congregation of talent, and treasure. Through including our local priests, parents, the Holy Cross. their generosity many wonderful and invited guests, came together things are happening at each of to hammer out a plan that would After three years of being our campuses. We are so grateful map out MCPS’s course. These a novitiate, he was denied to Partners in Catholic Education, people are the doormen for our admittance. -

Matthew C. Ehrlich (August 2015) 119 Gregory Hall, 810 S

Matthew C. Ehrlich (August 2015) 119 Gregory Hall, 810 S. Wright St., Urbana IL 61801; 217-333-1365 [email protected] OR [email protected] I. PERSONAL HISTORY AND PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Academic Positions Since Final Degree Currently Professor of Journalism and Interim Director of the Institute of Communications Research, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. 1992: Appointed Assistant Professor. 1998: Promoted to Associate Professor with tenure. 2006: Promoted to Professor with tenure. 2015: Appointed Interim Director, Institute of Communications Research. 1991-1992: Assistant Professor, School of Journalism and Mass Communication, University of Oklahoma. Educational Background 1991: Ph.D., University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Institute of Communications Research. 1987: M.S., University of Kansas, School of Journalism and Mass Communications. 1983: B.J., University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism. Journalism/Media Experience 1987-1991, WILL-AM, Urbana, IL. Served at various times as Morning Edition and Weekend Edition host for public radio station; hosted live call-in afternoon interview program; created and hosted award-winning weekend news magazine program; produced spot and in-depth news reports; participated in on-air fundraising. 1985-1987, KANU-FM, Lawrence, KS. Served as Morning Edition newscaster for public radio station; produced spot and in-depth news reports. 1985-1986, Graduate Teaching Assistant, University of Kansas. Supervised students in university’s radio and television stations and labs, including KJHK-FM. 1984-1985, KCUR-FM, Kansas City, MO. Produced spot and in-depth news reports for public radio station; hosted midday news magazine program. 1983-1984, KBIA-FM, Columbia, MO. Supervised University of Missouri journalism students in public radio newsroom; served as evening news host and editor. -

{PDF EPUB} Walt Disney: the Triumph of the American Imagination

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination by Neal Gabler Neal Gabler is the author of five books: An Empire of Their Own: How the Jews Invented Hollywood, Winchell: Gossip, Power and the Culture of Celebrity, Life the Movie: How Entertainment Conquered Reality, Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination, and, most recently, Barbra Streisand: Redefining Beauty, Femininity and Power for the Yale Jewish Lives series.Cited by: 131Author: Neal GablerReviews: 524Brand: VintageWalt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination by ...https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/118824“Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination” by Neal Gabler was published in 2006 and won the Los Angeles Times Book Prize for Biography. Gabler is an author, journalist and former film critic whose previous books include a biography of Barbra Streisand and a …4/5Ratings: 10KReviews: 662Videos of Walt Disney: The Triumph of The American Imagination … bing.com/videosWatch video25:17Neal Gabler on 'Walt Disney The Triumph of American Imagination'2.2K viewsApr 24, 2014YouTubetheatertalkWatch video8:52Walt Disney The Triumph Of The American Imagination Neal Gabler Book New277 viewsJan 22, 2020YouTubemoviefan8Watch video28:37Walt Disney: The Triumph of American Imagination2.8K viewsAug 13, 2008Internet ArchivejkarushWatch video on thirteen.orgWalt Disney: The Triumph of American Imagination | The ...thirteen.orgWatch video16:26Impact Books: Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination by …2.8K viewsApr 15, 2017YouTubeTom BilyeuSee more videos of Walt Disney: The Triumph of The American Imagination by Neal GablerWalt Disney - the Triumph of the American Imagination ...https://www.amazon.com/Walt-Disney-Triumph...This item: Walt Disney - the Triumph of the American Imagination by Neal gabler Paperback $20.74 Only 1 left in stock - order soon. -

![Download Music for Free.] in Work, Even Though It Gains Access to It](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0418/download-music-for-free-in-work-even-though-it-gains-access-to-it-680418.webp)

Download Music for Free.] in Work, Even Though It Gains Access to It

Vol. 54 No. 3 NIEMAN REPORTS Fall 2000 THE NIEMAN FOUNDATION FOR JOURNALISM AT HARVARD UNIVERSITY 4 Narrative Journalism 5 Narrative Journalism Comes of Age BY MARK KRAMER 9 Exploring Relationships Across Racial Lines BY GERALD BOYD 11 The False Dichotomy and Narrative Journalism BY ROY PETER CLARK 13 The Verdict Is in the 112th Paragraph BY THOMAS FRENCH 16 ‘Just Write What Happened.’ BY WILLIAM F. WOO 18 The State of Narrative Nonfiction Writing ROBERT VARE 20 Talking About Narrative Journalism A PANEL OF JOURNALISTS 23 ‘Narrative Writing Looked Easy.’ BY RICHARD READ 25 Narrative Journalism Goes Multimedia BY MARK BOWDEN 29 Weaving Storytelling Into Breaking News BY RICK BRAGG 31 The Perils of Lunch With Sharon Stone BY ANTHONY DECURTIS 33 Lulling Viewers Into a State of Complicity BY TED KOPPEL 34 Sticky Storytelling BY ROBERT KRULWICH 35 Has the Camera’s Eye Replaced the Writer’s Descriptive Hand? MICHAEL KELLY 37 Narrative Storytelling in a Drive-By Medium BY CAROLYN MUNGO 39 Combining Narrative With Analysis BY LAURA SESSIONS STEPP 42 Literary Nonfiction Constructs a Narrative Foundation BY MADELEINE BLAIS 43 Me and the System: The Personal Essay and Health Policy BY FITZHUGH MULLAN 45 Photojournalism 46 Photographs BY JAMES NACHTWEY 48 The Unbearable Weight of Witness BY MICHELE MCDONALD 49 Photographers Can’t Hide Behind Their Cameras BY STEVE NORTHUP 51 Do Images of War Need Justification? BY PHILIP CAPUTO Cover photo: A Muslim man begs for his life as he is taken prisoner by Arkan’s Tigers during the first battle for Bosnia in March 1992. -

Iraq: Options for U.S

THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE POLICY FOCUS IRAQ: OPTIONS FOR U.S. POLICY LAURIE MYLROIE RESEARCH MEMORANDUM NUMBER TWENTY-ONE MAY 1993 Cover and title page illustrations from windows of the tom Bi-AmnW Mosque. 990-1013 THE AUTHOR Laurie Mylroie is Arab Affairs Fellow at The Washington Institute. She has previously taught in the Department of Government at Harvard University and at the U.S. Naval War College. Among Dr. Mylroie's many published works on Iraq are Saddam Hussein and the Crisis in the Gulf (with Judith Miller), and The Future of Iraq (Washington Institute Policy Paper Number 24). The views expressed in this Policy Focus are those of the author and should not necessarily be construed as representing those of The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, its Board of Trustees, or its Board of Advisors. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Clinton administration inherited a flawed Iraq policy from the Bush administration, but, in formulating a new policy, it has failed to accurately define those flaws. Its emphasis on "depersonalizing" the conflict with Iraq by shifting the focus from Saddam Hussein to Baghdad's compliance with relevant UN resolutions may mean that the Clinton administration will eventually, if reluctantly, come to terms with Saddam's dogged hold on power and accept a diluted form of Iraqi compliance with the resolutions. Although that may be far from the administration's intent, the present formulation of U.S. policy may weaken the coalition and lead to that result nonetheless. The Clinton administration has stated that it will enforce all UN resolutions, including Resolution 687, which, inter alia, provides for stripping Iraq of weapons of mass destruction, and Resolution 688, which demands that Baghdad cease to repress its population. -

Common Sense Common Sense

CCOMMONOMMON SSENSEENSE GGOVERNMENTOVERNMENT WWORKSORKS BBETTERETTER &C&COSTSOSTS LLESSESS Vice President Al Gore Third ReportReport of of thethe National Performance Performance Review Review Common Sense Government Works Better and Costs Less Vice President Al Gore Third Report of the National Performance Review Contents Introduction.................................................................................................1 Calling in the Real Experts............................................................................1 There’s a Wrong Way and a Right Way .........................................................2 Reclaiming Government “For the People”.....................................................2 Delivering the Goods at Last.........................................................................6 It’s Never Finished.........................................................................................6 1. A Government That Makes Sense........................................11 The Real Business of Government ..............................................................12 Americans Want a Government That Works Better, Costs Less...................13 Why We Have a Federal Government.........................................................14 How Things Got Out of Hand...................................................................16 Failing to Change With a Changing World.................................................16 Going By the Book .....................................................................................18 -

THE TAKING of AMERICA, 1-2-3 by Richard E

THE TAKING OF AMERICA, 1-2-3 by Richard E. Sprague Richard E. Sprague 1976 Limited First Edition 1976 Revised Second Edition 1979 Updated Third Edition 1985 About the Author 2 Publisher's Word 3 Introduction 4 1. The Overview and the 1976 Election 5 2. The Power Control Group 8 3. You Can Fool the People 10 4. How It All BeganÐThe U-2 and the Bay of Pigs 18 5. The Assassination of John Kennedy 22 6. The Assassinations of Robert Kennedy and Dr. Martin Luther King and Lyndon B. Johnson's Withdrawal in 1968 34 7. The Control of the KennedysÐThreats & Chappaquiddick 37 8. 1972ÐMuskie, Wallace and McGovern 41 9. Control of the MediaÐ1967 to 1976 44 10. Techniques and Weapons and 100 Dead Conspirators and Witnesses 72 11. The Pardon and the Tapes 77 12. The Second Line of Defense and Cover-Ups in 1975-1976 84 13. The 1976 Election and Conspiracy Fever 88 14. Congress and the People 90 15. The Select Committee on Assassinations, The Intelligence Community and The News Media 93 16. 1984 Here We ComeÐ 110 17. The Final Cover-Up: How The CIA Controlled The House Select Committee on Assassinations 122 Appendix 133 -2- About the Author Richard E. Sprague is a pioneer in the ®eld of electronic computers and a leading American authority on Electronic Funds Transfer Systems (EFTS). Receiving his BSEE degreee from Purdue University in 1942, his computing career began when he was employed as an engineer for the computer group at Northrup Aircraft. He co-founded the Computer Research Corporation of Hawthorne, California in 1950, and by 1953, serving as Vice President of Sales, the company had sold more computers than any competitor. -

Raven Leilani the Novelist Makes a Shining Debut with Luster, a Mesmerizing Story of Race, Sex, and Power P

Featuring 417 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children'sand YA books KIRKUSVOL. LXXXVIII, NO. 15 | 1 AUGUST 2020 REVIEWS Raven Leilani The novelist makes a shining debut with Luster, a mesmerizing story of race, sex, and power p. 14 Also in the issue: Raquel Vasquez Gilliland, Rebecca Giggs, Adrian Tomine, and more from the editor’s desk: The Dysfunctional Family Sweepstakes Chairman BY TOM BEER HERBERT SIMON President & Publisher MARC WINKELMAN John Paraskevas # As this issue went to press, the nation was riveted by the publication of To o Chief Executive Officer Much and Never Enough: How My Family Created the World’s Most Dangerous Man MEG LABORDE KUEHN (Simon & Schuster, July 14), the scathing family memoir by the president’s niece. [email protected] Editor-in-Chief For the past four years, nearly every inhabitant of the planet has been affected TOM BEER by Donald Trump, from the impact of Trump administration policies—on [email protected] Vice President of Marketing climate change, immigration, policing, and more—to the continuous feed of SARAH KALINA Trump-related news that we never seem to escape. Now, thanks to Mary Trump, [email protected] Ph.D., a clinical psychologist, we understand the impact of Donald Trump up Managing/Nonfiction Editor ERIC LIEBETRAU close, on his family members. [email protected] It’s not a pretty picture. Fiction Editor LAURIE MUCHNICK The book describes the Trumps as a clan headed by a “high-functioning [email protected] Tom Beer sociopath,” patriarch Fred Trump Sr., father to Donald and the author’s own Young Readers’ Editor VICKY SMITH father, Fred Jr.