Title Birmingham Community Safety Partnership Public Space

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Warding Arrangements for Legend Ladywood Ward

Newtown Warding Arrangements for Soho & Jewellery Quarter Ladywood Ward Legend Nechells Authority boundary Final recommendation North Edgbaston Ladywood Bordesley & Highgate Edgbaston 0 0.1 0.2 0.4 Balsall Heath West Kilometers Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016. $ Bournville & Cotteridge Allens Cross Warding Arrangements for Longbridge & West Heath Ward Legend Frankley Great Park Northfield Authority boundary King's Norton North Final recommendation Longbridge & West Heath King's Norton South Rubery & Rednal 0 0.15 0.3 0.6 Kilometers Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016. $ Warding Arrangements for Lozells Ward Birchfield Legend Authority boundary Final recommendation Aston Handsworth Lozells Soho & Jewellery Quarter Newtown 0 0.05 0.1 0.2 Kilometers Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016. $ Small Heath Sparkbrook & Balsall Heath East Tyseley & Hay Mills Warding Balsall Heath West Arrangements for Moseley Ward Edgbaston Legend Authority boundary Final recommendation Sparkhill Moseley Bournbrook & Selly Park Hall Green North Brandwood & King's Heath Stirchley Billesley 0 0.15 0.3 0.6 Kilometers Hall Green South Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016. $ Perry Barr Stockland Green Warding Pype Hayes Arrangements for Gravelly Hill Nechells Ward Aston Legend Authority boundary Final recommendation Bromford & Hodge Hill Lozells Ward End Nechells Newtown Alum Rock Glebe Farm & Tile Cross Soho & Jewellery Quarter Ladywood Heartlands Bordesley & Highgate 0 0.15 0.3 0.6 Kilometers Bordesley Green Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016. $ Small Heath Handsworth Aston Warding Lozells Arrangements for Newtown Ward Legend Authority boundary Final recommendation Newtown Nechells Soho & Jewellery Quarter 0 0.075 0.15 0.3 Ladywood Kilometers Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database Ladywood right 2016. -

Central Print and Bindery 10–12 Castle Road Birmingham Kings Norton Driving Maps B30 3ES Edgbaston Park

Kings Norton Business Centre Central Print and Bindery 10–12 Castle Road Birmingham Kings Norton driving maps B30 3ES Edgbaston Park Cotteridge University A38 A441 Canon Hill University of Park A4040 Birmingham WATFORD ROAD BRISTOL ROAD A441 PERSHORE ROAD A4040 Bournebrook A38 Selly Oak Selly Park Selly Oak Park Selly Oak A441 B4121 PERSHORE ROAD PERSHORE Selly Park MIDDLETON HALL ROAD OAK TREE LANE Selly Oak Hospital A441 Muntz Park Stirchley University of Kings Norton Castle Road Birmingham A4040 Bournville BRISTOL ROAD Station Road A38 LINDEN ROAD Dukes Road Cadbury Sovereign Road World Bournville Sovereign Road Park Bournville A441 Cotteridge ROAD PERSHORE Camp Lane Woodlands Park Park A4040 Melchett Road Dukes Road Cotteridge WATFORD ROAD Cotteridge Sovereign Road A4040 PERSHORE ROAD A441 WATFORD ROAD Prince Road MIDDLETON HALL ROAD B4121 B4121 Prince Road A441 A441 Melchett Road Kings Norton PERSHORE ROAD Kings Norton walking map A441 B4121 A441 PERSHORE ROAD PERSHORE Walking directions from Kings Norton station: MIDDLETON HALL ROAD Turn left out of the station and turn left again towards the Pershore Road. Turn left and make your way to the Crossing pedestrian crossing (approx 90 metres). Press the button and wait for green man before crossing over the road. Kings Norton Castle Road Turn right and walk down the road (approx 90 metres) until you see a walkway on your left. At the end of the walkway, Station Road take care to cross Sovereign Road and enter the car park Dukes Road entrance directly opposite (the entrance before Castle Sovereign Road Sovereign Road Road). We are the second large building on the left with a large black University of Birmingham sign above the reception entrance. -

Cotteridge Meeting Newsletter

www.cotteridge.quaker.org.uk 1 November 2017/No.10 Cotteridge Meeting Newsletter Meeting for Worship every Sunday 10.30am Children’s Meeting in term time Diary Dates - November/December 19 November, Pineapple Jam will be playing and singing for us at Shared Lunch 26 November, 6pm, Meeting for Worship, Northfield Meeting House 30 November, Coffee Morning at Sarah J’s house, 10.30 - 12 noon. All welcome 2 December, Creative Day, Northfield MH, 10.00-4.00, details from Tina, 07802 413 143, all welcome 3 December, 12 noon, Local Business Meeting: Annual Review Thursday 7 December, Area Meeting, Bull Street, 6.15pm10 December, Mindful Gardening, 8am start 10 December, Midday - 12.30 sharp Come and join the conversation! Enquirers’ gathering - see page 2 16 December, 10.00-12.00, Reflections in the garden 17 December, All age Meeting for Worship and Shared lunch - details below 22 November, Staying Friends, details page 2 Political Night Prayer Footsteps - Tread Lightly on 7.30 – 9.00pm Sunday 26 November this Earth Annual Conference Cotteridge Church Sunday 19 November 2-5 pm Austerity: Abundance? at Birmingham Progressive Synagogue Political Night Prayer bringing together our concerns about austerity and our hope in God’s abundance For programme and more information see www.footsteps.peacehub.org.uk/treadlightly All age worship: 17th December On the 17th December children’s committee, with the support of elders, are planning to arrange all age worship. The worship will be on the theme of Christmas and will include a number of different elements including a collect of items for the food bank. -

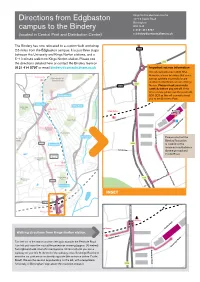

Directions from Edgbaston Campus to the Bindery

Kings Norton Business Centre Directions from Edgbaston 10–12 Castle Road Birmingham B30 3HZ campus to the Bindery t: 0121 414 5797 (located in Central Print and Distribution Centre) e: [email protected] Cotteridge The Bindery has now relocated to a custom-built workshop A4040 2.5 miles from the Edgbaston campus. It is just three stops WATFORD ROAD between the University and Kings Norton stations, and a 5–10 minute walk from Kings Norton station. Please see the directions detailed here or contact the Bindery team on A441 0121 414 5797 or email [email protected] Park Important sat nav information The official postcode is B30 3HZ. However, please be aware that some University A38 A441 Canon Hill University of Park sat nav systems incorrectly locate Birmingham another Castle Road outside of Kings A441 BRISTOL ROAD B4121 Norton. Please check your route PERSHORE ROAD PERSHORE carefully before you set off. If this MIDDLETON HALL ROAD PERSHORE ROAD error occurs, please use the postcode A4040 Bournebrook B30 3ES as this will correctly direct you to the Business Park. A38 Selly Oak Selly Park Selly Oak Park Selly Oak Kings Norton Castle BinderyRoad Reception Selly Park Station Road P OAK TREE LANE Selly Oak Sovereign Road Hospital A441 Sovereign Road Muntz Park Stirchley University of Please note that the Birmingham Bindery Reception A4040 Bournville A441 is located on the unnamed road between BRISTOL ROAD Camp Lane Sovereign road and A38 LINDEN ROAD Castle Road. Melchett Road Cadbury Cotteridge Bournville World Park Sovereign Road A4040 PERSHORE ROAD Bournville WATFORD ROAD Prince Road A441 Prince Road PERSHORE ROAD PERSHORE Cotteridge ROAD PERSHORE A441 Woodlands Park Park A4040 Melchett Road WATFORD ROAD Cotteridge A441 INSET A441 MIDDLETON HALL ROAD B4121 B4121 B4121 PERSHORE ROAD PERSHORE MIDDLETON HALL ROAD Kings Norton PERSHORE ROAD Crossing Kings Norton Castle Road A441 Walking directions from Kings Norton station: Station Road Turn left out of the station and turn left again towards the Pershore Road. -

Longbridge Centres Study Good Morning / Afternoon / Evening. I Am

Job No. 220906 Longbridge Centres Study Good morning / afternoon / evening. I am ... calling from NEMS Market Research, we are conducting a survey in your area today, investigating how local people would like to see local shops and services improved. Would you be kind enough to take part in this survey – the questions will only take a few minutes of your time ? QA Are you the person responsible or partly responsible for most of your household's shopping? 1 Yes 2No IF ‘YES’ – CONTINUE INTERVIEW. IF ‘NO’ – ASK - COULD I SPEAK TO THE PERSON WHO IS RESPONSIBLE FOR MOST OF THE SHOPPING? IF NOT AVAILABLE THANK AND CLOSE INTERVIEW Q01 At which food store did you last do your household’s main food shopping ? DO NOT READ OUT. ONE ANSWER ONLY. IF 'OTHER' PLEASE SPECIFY EXACTLY STORE NAME AND LOCATION Named Stores 01 Aldi, Cape Hill, Smethwick 02 Aldi, Selly Oak 03 Aldi, Sparkbrook 04 Asda, Bromsgrove 05 Asda, Merry Hill 06 Asda, Oldbury 07 Asda, Small Heath / Hay Mills 08 Co-op, Maypole 09 Co-op, Rubery 10 Co-op Extra, Stirchley 11 Co-op, West Heath 12 Iceland, Bearwood 13 Iceland, Bromsgrove 14 Iceland, Harborne 15 Iceland, Halesowen 16 Iceland, Kings Heath 17 Iceland, Northfield 18 Iceland, Shirley 19 Kwik Save, Stirchley 20 Lidl, Balsall Heath 21 Lidl, Dudley Road 22 Lidl, Silver Street, Kings Heath 23 Marks & Spencer, Harborne 24 Morrisons, Birmingham Great Park 25 Morrisons, Bromsgrove 26 Morrisons, Redditch 27 Morrisons, Shirley (Stratford Road) 28 Morrisons, Small Heath 29 Netto, Warley 30 Sainsburys, Blackheath, Rowley Regis 31 Sainsburys, -

Cotteridge LM

Friends Meeting House, Cotteridge 23a Watford Road, Birmingham, B30 1JB National Grid Reference: SP 04744 79838 Statement of Significance The building has medium heritage significance as a meeting house purpose- built in 1964, in a modernist style with a striking butterfly roof by local architect Frederick W Gregory. Evidential value Cotteridge meeting house has an overall low level of significance for evidential value. The Birmingham Historic Environment Record has not identified the site for any archaeological interest. Historical value Being of relatively recent date, the meeting house has low historical value. Together with the former Mission Hall on the site, it provides some local context into the recent history of Quakerism in Cotteridge. Aesthetic value The meeting house has a functional modern design, typical of the post-war period; it has medium aesthetic value. The butterfly roof is an attractive feature and creates a dramatic space internally. Communal value The meeting house has high communal value as a building developed for the Quakers which has been in use since it opened in 1964. The building has in recent years provided a local community focus and its facilities are used by many local and social groups with diverse interests. Part 1: Core data 1.1 Area Meeting: Central England 1.2 Property Registration Number: 0026440 1.3 Owner: Area Meeting 1.4 Local Planning Authority: Birmingham City Council 1.5 Historic England locality: West Midlands 1.6 Civil parish: Birmingham 1.7 Listed status: Not listed 1.8 NHLE: Not applicable 1.9 Conservation Area: No 1.10 Scheduled Ancient Monument: No 1.11 Heritage at Risk: No 1.12 Date: 1964 1.13 Architect: Frederick W Gregory 1.14 Date of visit: 7 November 2015 1.15 Name of report author: Emma Neil 1.16 Name of contact made on site: Harriet Martin 1.17 Associated buildings and sites: Not applicable 1.18 Attached burial ground: No 1.19 Information sources: Butler, D.M., The Quaker Meeting Houses of Britain (London: Friends Historical Society, 1999), vol. -

Title Birmingham Community Safety Partnership Annual Report (2018

Title Birmingham Community Safety Partnership Annual Report (2018-19) Date 26th September 2019 Report Cllr John Cotton (Chair, Birmingham Community Safety Partnership/ Cabinet Author Member – Social Inclusion, Community Safety and Equalities) Chief Superintendent John Denley (Vice Chair, Birmingham Community Safety Partnership/ NPU Commander, Birmingham West) 1. Purpose 1.1 This annual report provides an overview of Birmingham Community Safety Partnership (BCSP) activity and impact during 2018-19. However, the report will refer to more recent information and activity to provide a more up to date context for the Committee. 1.2 Additional and more detailed information can be provided to the Committee on individual areas of business, if required. 2. Background 2.1 The Crime and Disorder Act (1997) mandated all local authority areas to establish Crime and Disorder Partnerships. In Birmingham, this partnership is referred to as the Birmingham Community Safety Partnership (BCSP). 2.2 The core membership of the BCSP includes all Responsible Authorities. These include: Birmingham City Council; Birmingham Children’s Trust; West Midlands Police; West Midlands Fire Service; National Probation Service; Community Rehabilitation Company and Birmingham and Solihull Clinical Commissioning Group. Co-opted members are Birmingham Social Housing Partnership and Birmingham and Solihull Mental Health Trust. 2.3 2.3 The BCSP has responsibility for discharging the following statutory requirements: Work together to form and implement strategies to prevent and reduce crime and anti-social behaviour, and the harm caused by drug and alcohol misuse. This will include producing an annual plan. Produce plans to reduce reoffending by adults and young people Manage the Community Trigger process Commission Domestic Homicide Reviews Serious Violence – this is a new duty and we are waiting for further information from Government on how this will be delivered. -

Bournville Parks

Bournville Parks (Circular route) 6km (3.5 miles) An easy flat walk, on paved paths all the way except one 150 yard stretch. Can be cycled, but the bicycle will have to be pushed through Cadbury’s grounds and up one flight of steps. Access Points: Walk is circular so can be started anywhere along route. The suggested start point is the Car Park for Cotteridge Park in Franklin Road (Leaflet Map Reference D7). The no. 11 bus (outer circle) stops in Linden Road close to end of Franklin Road. The nearest station is Bournville. Points of Interest: Picturesque circular walk following parts of the Wood Brook and Bourn Brooks through Woodlands, and Bournville Parks. The walk also includes Cotteridge and Rowheath Parks. Other points of interest include Victorian alms houses, terraced housing (note house names), Rowheath Pavilion, The Cadbury Factory and original Cadbury shops, Bournville Green and the Carillon, Selly Manor, and a model yachting pool. In spring there are lots of spring flowers and blossom. Refreshments: Shops at the junction of Mary Vale Road and Linden Road; Teas/Lunches and Bar at the Rowheath Pavilion. Row of shops at the Bournville Green and coffee shop set back at end of shops. Nearest pub:- Cotteridge Inn (Pershore Road South – short way beyond Kings Norton station). Walk Details: 1… From the Franklin Road Car Park, take the path downhill that leads to the tennis courts. Just past the tennis courts, turn left along path and take right path over a bridge across an unnamed tributary of the River Rea and up some steps. -

Interconnect Improving the Journey Experience Interconnect: Improving the Journey Experience

Interconnect Improving the journey experience Interconnect: Improving the journey experience Piloted in the centre of Birmingham, UK, Interconnect Interconnect delivers a visionary blueprint seeks to improve the journey experience for people living for connecting the journey experience. in and visiting the West Midlands region. The project seeks to improve the quality of information across all media channels, transport services and public environments. Interconnect is a partnership, project In turn the approach is helping attract and innovative design approach focused visitors, tourism and investment that will on improving the ‘interface’ between support new jobs and a stronger economy, people, places and transport systems. building the reputation of the region The project promotes a vision of a internationally and contributing towards world class movement network with social, environmental and economic infrastructure and passenger facilities benefi ts for all. designed to create welcoming places In support of the vision, the Interconnect supported by legible and intuitive partnership is encouraging new ways information systems. of working, enabling organisations Piloted for the fi rst time in the West to plan, develop and deliver effective Midlands region of the United Kingdom, improvements to the journey experience. Interconnect aims to improve the journey The Interconnect partners are sharing experience for people, whether they are knowledge, identifying mutually benefi cial visiting for the fi rst time, or making their opportunities and maximising investment daily commute. – delivering major improvements for Investment in ongoing regeneration everyone who lives and works in, or and renewal projects is delivering radical visits the region. changes to the region. The benefi ts of This publication will be of value to other this investment are being maximised places, cities and regions who wish to by interconnecting transport, tourism, improve the journey experience. -

THE LONDON (GAZETTE, 26Ra JUNE 1980

9186 THE LONDON (GAZETTE, 26ra JUNE 1980 under the style of " Floodgate Engineering ", at 14 Flood- aforesaid, previously carrying on business at 17 Lans- gate Street, Birmingham 5 aforesaid, and at 35 Meriden down Place Terrace, Cheltenham aforesaid and before Street, Birmingham 5 aforesaid, and previously carrying that carrying on business at Ingot Works, Charlotte Road, on business in partnership with others as ENGINEERS, Stirchley, Birmingham aforesaid and before that at 1894 under the style of "Floodgate Engineering Co." at 14 Pershore Road, Cotteridge, Birmingham aforesaid and Floodgate Street aforesaid. Court—BIRMINGHAM. before that at 107 Addison Road, Kings Heath, Birming- No. of Matter—37A of 1975. Date Fixed for Hearing— ham aforesaid and before that from premises at Alve- 6th August 1980. 10.15 a.m. Place—The Court Office church in the county of Hereford and Worcester under Building, 2 Newton Street, Birmingham B4 7LU. one or more of the styles "T & R Engineering Com- pany" (initially in co-partnership) as an Industrial and HENDREN William, residing at 69 Pool Farm Road, Garage Equipment Repairer, " May Kay Road Services Acocks Green, Birmingham B27 7HB in the metropoli- Company", " T & R Road Services Cheltenham" and tan county of West Midlands, unemployed. Court— "T & R Road Services Company" (in co-partnership), BIRMINGHAM. No. of Matter—36 of 1975. Date all as a ROAD HAULAGE CONTRACTOR, " Kings- Fixed for Hearing—6th August 1980. 10.15 a.m. Place ditch Private Hire Company ", " Blenheim Private Hire " —The Court Office Building, 2 Newton Street, Birming- (in co-partnership), and " T & R Car Hire Company", ham 4. -

20Mph Area B2 – Consultation Summary

Appendix F 20MPH AREA B2 – CONSULTATION SUMMARY Comments Response Gisela Stuart (MP) No response received. Follow-up e-mail sent on 07/10/2016 I am writing in support of proposals to introduce 20mph speed limits on Birmingham’s residential roads to improve safety and reduce the number of accidents. As previously stated in response to the 2013 consultation I think these proposals offer Birmingham an opportunity to become safer for pedestrians and cyclists. Steve McCabe (MP) I do have concerns about clarity for motorists and hope that adequate As these are 20mph pilots, the intension is to see whether information and signs are available to ensure that all car drivers know areas wide 20mph could be delivered simply by installing what the speed limit is on whatever road they happen to be on in signs and lines, thereby enabling us to cover larger areas of Birmingham. the city. However the scheme will be designed to ensure there are sufficient signs and carriageway markings to inform the drivers that they are in the 20mph Area. Bournville Ward Councillors 1. All the side roads off Fordhouse Lane should be 20 mph roads i.e. 1. Fordhouse Lane is proposed to remain at 30mph and Barn Close, The Worthings, Harvest Close, Beilby Road, Windsor Road, the small cul-de-sacs off Fordhouse Lane have been Oakley Road and Dacer Close are all proposed to remain at 30 mph. left at 30mph as they are less than 200m long. In This is ridiculous. accordance with the guidance provided by DFT, the minimum length of a speed limit should be 300m. -

Selly Oak District Profile Using the Power of Sport and Physical Activity to Improve Lives Selly Oak District Profile

Selly Oak District Profile Using the power of sport and physical activity to improve lives Selly Oak District Profile This is our first edition of the Birmingham profiles, a document we’re looking to improve and update throughout the next few years. The insight should provide key localised information to partners, stakeholders and those involved in sport to help shape projects. As a resource it can inform funding bids and help identify the challenges faced across the city. It is worth noting this is a easy to read guide for more information please head to our website or feel free to contact our insight officer: [email protected] If you would like to be involved in future profiles for the city be sure to give us a shout across our social media platforms. twitter.com/ instagram.com/ facebook.com/ sportbirmingham sportbirmingham sportbham Sport Birmingham’ is a trading name of Birmingham Sport and Physical Activity Trust limited, a companywith charitable status registered in England & Wales registered company number: 08177159 registered charity number: 1155171. With its registered office at Sport Birmingham, Floor 11, Cobalt Square, 83-85 Hagley Rd, Birmingham, West Midlands, B16 8QG Selly Oak District Profile DEMOGRAPHICS The population in Birmingham is due to increase by 7% to 1.21million in 20272. Selly Oak is a relatively young area compared to England generally, but is slightly older than the overall population of Birmingham. Can you help to meet the activity needs of this growing population? 107k 49% 51% Average Age 46% Selly Oak District Profile DEMOGRAPHICS Almost three-quarters of the population of Selly Oak is from a White British background, much higher than generally in Birmingham.