Ideology in Physics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

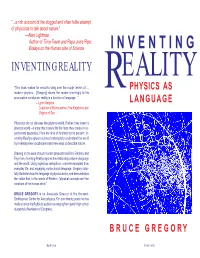

INVENTING REALITY EALITY “This Book Makes for Smooth Riding Over the Rough Terrain of

“...a rich account of the dogged and often futile attempt of physicists to talk about nature.” —Alan Lightman Author of Time Travel and Papa Joe’s Pipe: Essays on the Human side of Science INVENTING INVENTING REALITY EALITY “This book makes for smooth riding over the rough terrain of ... PHYSICS AS modern physics... [Gregory] steers the reader unerringly to his provocative conclusion: reality is a function of language...” R —Lynn Margulis LANGUAGE Coauthor of Microcosmos, Five Kingdoms, and Origins of Sex Physicists do not discover the physical world. Rather, they invent a physical world—a story that closely fits the facts they create in ex- perimental apparatus. From the time of Aristotle to the present, In- venting Reality explores science’s attempts to understand the world by inventing new vocabularies and new ways to describe nature. Drawing on the work of such modern physicists as Bohr, Einstein, and Feynman, Inventing Reality explores the relationship between language and the world. Using ingenious metaphors, concrete examples from everyday life, and engaging, nontechnical language, Gregory color- fully illustrates how the language of physics works, and demonstrates the notion that, in the words of Einstein, “physical concepts are free creations of the human mind.” BRUCE GREGORY is an Associate Director of the Harvard- Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. For over twenty years he has made science intelligible to audiences ranging from junior high school students to Members of Congress. B R U C E G R E G O R Y Back cover Front cover INVENTING INVENTING REALITY REALITY PHYSICS AS LANGUAGE ❅ Bruce Gregory For Werner PREFACE Physics has been so immensely successful that it is difficult to avoid the conviction that what physicists have done over the past 300 years is to slowly draw back the veil that stands between us and the world as it really is—that physics, and every science, is the discovery of a ready-made world. -

Spacetime Warps and the Quantum World: Speculations About the Future∗

Spacetime Warps and the Quantum World: Speculations about the Future∗ Kip S. Thorne I’ve just been through an overwhelming birthday celebration. There are two dangers in such celebrations, my friend Jim Hartle tells me. The first is that your friends will embarrass you by exaggerating your achieve- ments. The second is that they won’t exaggerate. Fortunately, my friends exaggerated. To the extent that there are kernels of truth in their exaggerations, many of those kernels were planted by John Wheeler. John was my mentor in writing, mentoring, and research. He began as my Ph.D. thesis advisor at Princeton University nearly forty years ago and then became a close friend, a collaborator in writing two books, and a lifelong inspiration. My sixtieth birthday celebration reminds me so much of our celebration of Johnnie’s sixtieth, thirty years ago. As I look back on my four decades of life in physics, I’m struck by the enormous changes in our under- standing of the Universe. What further discoveries will the next four decades bring? Today I will speculate on some of the big discoveries in those fields of physics in which I’ve been working. My predictions may look silly in hindsight, 40 years hence. But I’ve never minded looking silly, and predictions can stimulate research. Imagine hordes of youths setting out to prove me wrong! I’ll begin by reminding you about the foundations for the fields in which I have been working. I work, in part, on the theory of general relativity. Relativity was the first twentieth-century revolution in our understanding of the laws that govern the universe, the laws of physics. -

Views Expressed Are Those of the 37086

Dædalus coming up in Dædalus: Dædalus on learning Alison Gopnik, Howard Gardner, Jerome Bruner, Susan Carey, Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences Elizabeth Spelke, Patricia Smith Churchland, Clark Glymour, Daniel John Povinelli, and Michael Tomasello Fall 2003 Fall 2003: on science Fall on happiness Martin E. P. Seligman, Richard A. Easterlin, Martha C. Nussbaum, on science Alan Lightman A sense of the mysterious 5 Anna Wierzbicka, Bernard Reginster, Robert H. Frank, Julia E. Annas, Roger Shattuck, Darrin M. McMahon, and Ed Diener Albert Einstein Physics & reality 22 Gerald Holton Einstein’s Third Paradise 26 on progress Joseph Stiglitz, John Gray, Charles Larmore, Randall Kennedy, Peter Pesic Bell & buzzer 35 Sakiko Fukuda-Parr, Jagdish Bhagwati, Richard A. Shweder, and David Pingree The logic of non-Western science 45 others Susan Haack Trials & tribulations 54 Andrew Jewett Science & the promise of democracy on human nature Steven Pinker, Lorraine Daston, Jerome Kagan, Vernon Smith, in America 64 Joyce Appleby, Richard Wrangham, Patrick Bateson, Thomas Sowell, Jonathan Haidt, and Donald Brown poetry Les Murray The Tune on Your Mind & Photographing Aspiration 71 on race Kenneth Prewitt, Orlando Patterson, George Fredrickson, Ian Hacking, Jennifer Hochschild, Glenn Loury, David Hollinger, ½ction Joanna Scott That place 73 Victoria Hattam, and others notes Elizabeth F. Loftus on science under legal assault 84 Perez Zagorin on humanism past & present 87 plus poetry by David Ferry, Richard Wilbur, Franz Wright, Rachel Hadas, W. S. Merwin, Charles Wright, Richard Howard &c.; ½ction by Chuck Wachtel &c.; and notes by Gerald Early, Linda Hutcheon, Jennifer Hochschild, Charles Altieri, Richard Stern, Donald Green, S. -

I Speculative Physics: the Ontology of Theory And

Speculative Physics: the Ontology of Theory and Experiment in High Energy Particle Physics and Science Fiction by Clarissa Ai Ling Lee Graduate Program in Literature Duke University Date: _______________________ Approved: ___________________________ N. Katherine Hayles, Co-Supervisor ___________________________ Mark C. Kruse, Co-Supervisor ___________________________ Mark B. Hansen ___________________________ Andrew Janiak ___________________________ Timothy Lenoir Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate Program in Literature in the Graduate School of Duke University 2014 i v ABSTRACT Speculative Physics: the Ontology of Theory and Experiment in High Energy Particle Physics and Science Fiction by Clarissa Ai Ling Lee Graduate Program in Literature Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ N. Katherine Hayles, Co-Supervisor ___________________________ Mark C. Kruse, Co-Supervisor ___________________________ Mark B. Hansen ___________________________ Andrew Janiak ___________________________ Timothy Lenoir An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate Program in Literature in the Graduate School of Duke University 2014 i v Copyright by Clarissa Ai Ling Lee 2014 Abstract The dissertation brings together approaches across the fields of physics, critical theory, literary studies, philosophy of physics, sociology of science, and history of science to synthesize a hybrid approach for instigating more rigorous and intense cross- disciplinary interrogations between the sciences and the humanities. I explore the concept of speculation in particle physics and science fiction to examine emergent critical approaches for working in the two areas of literature and physics (the latter through critical science studies), but with the expectation of contributing new insights to media theory, critical code studies, and also the science studies of science fiction. -

I Continue Quoting from Alan Lightman's, "A Modern Day Yankee in a Connecticut Court and Other Essays on Science"

I continue quoting from Alan Lightman's, "A Modern Day Yankee In A Connecticut Court and other essays on Science". Conversations with Papa Joe The Fourth Evening "The next day I stayed home to prepare some lectures, but my heart wasn't in it. I spent the time reading a novel instead, sitting in Papa Joe's chair. That night the old gentleman returned as he had promised, and wasted no time in getting to the topic of conversation. "Now, I'm not afraid of numbers, young man," he began. "A fellow in construction for forty years knows numbers." He paused. "But I don't understand about equations. And I especially don't understand why you put so much stock in them." I got out a sheet of paper and wrote down: C = 2 pi r "Papa Joe, this says that the circumference of a circle equals its radius times two, times pi, a special number close to 3.14." "I remember that rule," my great-grandfather said. "The real strength of equations is their logic," I said. "You start at one point, and an equation tells you what has to come next, according to logic. In the example here, you give the radius of any circle, and this equation says what its circumference has to be. I think the Babylonians or somebody figured the thing out first. They went out and measured the radii and the circumferences of a whole bunch of circles, of all different sizes, and gradually realized that a precise mathematical law held every time. It saved them a lot of trouble when they found it. -

Freshman Survey

Academic Violations Yes, a couple of incidents. My freshman year I took Latin with a wonderful teacher. She also taught greek (which I wasn't in) and had about 3 boys who she suspected of cheating the entire semester. She finally caught them cheating on their final but unfortunately, at the time my school did not have an academic honesty code so they were not punished. Partially because of this incident my school implemented an academic honesty code so in my junior year when someone attempted to plagiarize their summer AP History paper they received a 0 for a grade. In 11th grade, we had to write a paper on two books that we had read for English and roughly 30-40 kids plagiarized by taking information off of spark notes. The punishment included a 0 on the paper as well as an in- school-suspension (ISS) in the extreme cases. Yes, my junior year in Computer Science AB. Students got into the habit of copying other peoples labs (including simple copy-and-past of Java files) and turning them in. My teacher, Mr. Wittry, ran JPlag on all the labs, and a lot of people got caught cheating. Yes, four students at my old school repeatedly snuck into the school after school hours and stole test answers from the testing center. As their punishment, they were suspended for different amounts of time (depending on the degree of their involvement) and indefinitely suspended from athletic teams and other extracurricular activities. Also, they were given failing grades for the classes they cheated in. -

Genesis: Science and the Beginning of Time

Genesis: Science and the Beginning of Time Raymond L. Orbach Director Office of Science U.S. Department of Energy American Association for the Advancement of Science Annual Meeting Denver, Colorado Friday, 14 February, 2002 6:30 PM – 7:30 PM ABSTRACT Humankind has always been concerned with its origins, its place in the universe, and its future prospects. The Bible, a sacred epic, begins with: “B'reishit bara' Elohim et ha- shamayim v'et ha-aretz,” or “In the beginning, God created the heaven and the earth.” The first three lines, Genesis I:1-3, are an inspiring statement of creation. Modern science is attempting to understand in its own terms the evolution of our universe from “the beginning.” This talk will explore what has been learned to date, and what more we hope to learn, using observation, theory, and computational simulations for our beginning, existence, and future. INTRODUCTION [Musical background: “In the Beginning God,” Duke Ellington1] In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth. Now the earth was unformed and void, And darkness was upon the face of the deep, And the Spirit of God hovered over the face of the waters. And God said: “Let there be light. And there was light.” (Genesis I:1-3) “Mankind is led into the darkness beyond our world by the inspiration of discovery and the longing to understand.” (President of the United States, George W. Bush, Sunday, February 2, 2003, mourning the loss of the seven crew members of the Shuttle Columbia) Since the earliest humans first noticed the stars above us, we have longed to understand the heavens. -

A Selected Bibliography of Publications By, and About, George Gamow

A Selected Bibliography of Publications by, and about, George Gamow Nelson H. F. Beebe University of Utah Department of Mathematics, 110 LCB 155 S 1400 E RM 233 Salt Lake City, UT 84112-0090 USA Tel: +1 801 581 5254 FAX: +1 801 581 4148 E-mail: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] (Internet) WWW URL: http://www.math.utah.edu/~beebe/ 08 March 2021 Version 1.94 Title word cross-reference $1.95 [Smi61a]. $16.95 [Hob02]. $2.50 [Ano55a]. $2.75 [Joh54a]. $24.95 [Hob02]. $35.00 [Dys02]. $5.75 [Sit64b]. α [CG30, Gam29d, Gam30b, Gam32a, Gam33b, MP31, Rut27]. αβγ [AWCT09, Tur08]. β [Gam33e, Gam34a, GT36, Gam37b, GT37, HS19]. c [Gam39c]. G [Gam39c]. γ [BG36, Gam33e, Gam75a, MP31]. h [Gam39c]. p [Gam32a]. -and [Gam32a]. -Disintegration [Gam33e, GT36]. -Excitation [Gam33e]. -Feinstruktur [MP31]. -levels [Gam32a]. -Particles [CG30, Gam33b]. -Ray [BG36]. -Rays [Gam30b, Gam75a, Rut27]. -Spektrum [MP31]. -Transformation [GT37]. -Transformations [Gam29d]. -Zerfalls [Gam34a, Gam37b]. 0 [Dys02]. 0-521-63009-6 [Per03]. 0-521-63992-1 [Per03]. 0-7382-0532-X 1 2 [Dys02]. 1 [Gam37b, UM86a]. 19 [Ano69, Opi69].¨ 1911 [Meh75]. 1930/41 [Fer68, Fer71]. 1933 [CCJ+34, Gam37b]. 1934 [Gam34a]. 1941 [TGF41]. 1960s [Mla98]. 1968 [Huf09, Wei68]. 1982 [MR86]. 1986 [Dys87]. 1993 [Boy93]. 1994 [BCY95]. 1997 [Ano98]. 2 [Cas12a, UM86b]. 20 [Gam34a]. 2001 [Ano02]. 2005 [BL09]. 2009 [CBKZ+09]. 2010 [KLR13]. 20th [Sha07]. 22 [CCJ+34]. 4th [CBKZ+09]. 60th [MF69]. 6th [Rya06]. 70th [Ano55a]. 75th [Gam60]. 80th [MW88]. 9.80 [Uns60]. 90th [Fre94a]. 978 [Cas12a]. 978-0-670-02276-2 [Cas12a]. 9th [CBKZ+09]. ˚ar [Gam66g, Gam68e]. -

PDF of This Issue

MIT's The Weather Oldest and Largest Today: Mostly sunny, 64°F (18°C) Tonight: Partly cloudy, 48°F (9°C) Newspaper Tomorrow: Few showers, 62°F (17°C) Details, Page 2 Volume 123, Number 44 Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139 Tuesday, September 30, 2003 DonnitDries Discuss In-House Dining Plans Faculty By Waseem S. Daher opening. Dorms consider dining possibility 1bReview MacGregor House and McCormick Hall are discussing "We've been looking into reopening in-house dining halls that reopening the McCormick dining were closed ten years ago because hall for about four or five years," GIRs MIT's dining contractor could not said Professor Charles Stewart III, make money off of them. the McCormick housemaster. By Beckett W. Sterner The idea is receiving serious "The McCormick dining hall NEWS EDITOR consideration by the dormitories was a great place to go to ten years MIT will launch a review of the and MIT administrators led by ago, and we'd like to bring that undergraduate General Institute Larry G. Benedict, the dean for stu- back," Stewart said. Requirements to consider the effects dent life. Last spring, McCormick's dining of changes that have occurred in the "We're exploring what it would committee investigated the issue by student body. take from an engineering stand- administering a survey to In the next month, MIT Presi- point," said Richard D. Berlin III, McCormick residents "to try to dent Charles M. Vest said he will the director of campus dining. ascertain what people's dining appoint a task force responsible for McCormick and MacGregor din- habits were [and] what kind of reevaluating the GIRs, including the ing would likely be patterned after options they were interested in," he common science requirements for existing models in Simmons, Baker, said. -

Daedalus Wi2002 On-Inequality.Pdf

Dædalus coming up in Dædalus: Dædalus on intellectual Richard Posner, Carla Hesse, Arnold Relman & Marcia Angell, Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences property Daniel Kevles, Lawrence Lessig, Adrian Johns, James Boyle, Rebecca Eisenberg & Richard Nelson, Roger Chartier, Arthur Winter 2002 Goldhammer, and classic texts by Diderot and Condorcet; plus a poem by Paul Muldoon, a story by Frederick Busch, and notes Winter 2002: on inequality by Wendy Doniger, Roald Hoffmann, W. G. Runciman, and Leo Breiman comment Ira Katznelson Evil & politics 7 on education Diane Ravitch, with comments by Howard Gardner, Theodore on inequality James K. Galbraith A perfect crime: global inequality 11 after the Sizer, E. D. Hirsch, Jr., Deborah Meier, Patricia Graham, Orlando Patterson Beyond compassion 26 culture wars Thomas Bender, Joyce Appleby, Robert Boyers, Catharine Stimpson, and Andrew Delbanco; plus Antonio Gramsci, Jeffrey Richard A. Epstein Against redress 39 Mirel, and Joel Cohen & David Bloom Christopher Jencks Does inequality matter? 49 Sean Wilentz America’s lost egalitarian tradition 66 on beauty Susan Sontag, Arthur C. Danto, Denis Donoghue, Dave Hickey, James F. Crow Unequal by nature: a geneticist’s perspective 81 Alexander Nehamas, Robert Campbell, David Carrier, Ernst Mayr The biology of race 89 Margo Jefferson, Kathy L. Peiss, Nancy Etcoff, and Martha C. Nussbaum Sex, laws & inequality: India’s experience 95 Gary William Flake Robert W. Fogel & Chulhee Lee Who gets health care 107 on international Stanley Hoffmann, Martha C. Nussbaum, Jean Bethke Ian Shapiro Why the poor don’t soak the rich 118 justice Elshtain, Stephen Krasner & Jack Goldsmith, Gary Bass, David Rieff, Anne-Marie Slaughter, Charles R. -

A Cross- Cultural Examination of Individualism and Human Dignity

THE PRIDE OF THE “COTTON-CLAD”: A CROSS- CULTURAL EXAMINATION OF INDIVIDUALISM AND HUMAN DIGNITY Yang Ye Abstract: Max Weber attributes the rise of modern Western society to Puritanism, noting that the Calvinist Protestant found, in his lonely attempt to communicate directly with God, a sense of human dignity and individualism in agreement with the rational structure of democracy. Weber, however, asserts that Confucianism lacks the Protestant way of thinking and hence cannot help with the rise of a modern Chinese society. This essay finds illustrations of Weber’s theory about the West in European civilian intellectuals who confronted authority with dignity, leading to the contemporary tradition of Western intellectuals “as the author of a language that tries to speak truth to power.” It also challenges Weber’s fallacy about China through a study of the varied attitudes of the individual vs. the state in Daoism, Buddhism and Confucianism, in the formation of a convention known as “the Pride of the Cotton-Clad,” which may play a role in building a state governed by law and justice and a society that respects all its citizens. I THE GERMAN sociologist Max Weber (1864-1920) has attributed the rise of capitalism and the modern Western political and social structure to that of Puritanism, and he has observed that the Calvinist Protestant found in his inner sense of loneliness, in excluding all mediators between himself and God and in trying to communicate directly with God, a sense of human dignity. This in turn brought about a kind of individualism in agreement with the rational structure of modern Western society. -

Niels Bohr 31 Wolfgang Pauli 41 Paul Dirac 47 Roger Penrose 58 Stephen Hawking 68 Schrodinger

Philosophy Reference, Philosophy Digest, Physics Reference and Physics Digest all contain information obtained from free cites online and other Saltafide resources. PHYSICS REFERENCE NOTE highlighted words in blue can be clicked to link to relevant information in WIKIPEDIA. Schrodinger 2 Heisenberg 6 EINSTEIN 15 MAX PLANCK 25 Niels Bohr 31 Wolfgang Pauli 41 Paul Dirac 47 Roger Penrose 58 Stephen Hawking 68 Schrodinger Schrodinger is probably the most important scientist for our Scientific Spiritualism discussed in The Blink of An I and in Saltafide..Schrödinger coined the term Verschränkung (entanglement). More importantly Schrodinger discovered the universal connection of consciousness. It is important to note that John A. Ciampa discovered Schrodinger’s connected consciousness long after writing about it on his own. At the close of his book, What Is Life? (discussed below) Schrodinger reasons that consciousness is only a manifestation of a unitary consciousness pervading the universe. He mentions tat tvam asi, stating "you can throw yourself flat on the ground, stretched out upon Mother Earth, with the certain conviction that you are one with her and she with you”.[25]. Schrödinger concludes this chapter and the book with philosophical speculations on determinism, free will, and the mystery of human consciousness. He attempts to "see whether we cannot draw the correct non-contradictory conclusion from the following two premises: (1) My body functions as a pure mechanism according to Laws of Nature; and (2) Yet I know, by incontrovertible direct experience, that I am directing its motions, of which I foresee the effects, that may be fateful and all-important, in which case I feel and take full responsibility for them.