American University Library ^

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mount Lebanon 4 Electoral District: Aley and Chouf

The 2018 Lebanese Parliamentary Elections: What Do the Numbers Say? Mount Lebanon 4 Electoral Report District: Aley and Chouf Georgia Dagher '&# Aley Chouf Founded in 1989, the Lebanese Center for Policy Studies is a Beirut-based independent, non-partisan think tank whose mission is to produce and advocate policies that improve good governance in fields such as oil and gas, economic development, public finance, and decentralization. This report is published in partnership with HIVOS through the Women Empowered for Leadership (WE4L) programme, funded by the Netherlands Foreign Ministry FLOW fund. Copyright© 2021 The Lebanese Center for Policy Studies Designed by Polypod Executed by Dolly Harouny Sadat Tower, Tenth Floor P.O.B 55-215, Leon Street, Ras Beirut, Lebanon T: + 961 1 79 93 01 F: + 961 1 79 93 02 [email protected] www.lcps-lebanon.org The 2018 Lebanese Parliamentary Elections: What Do the Numbers Say? Mount Lebanon 4 Electoral District: Aley and Chouf Georgia Dagher Georgia Dagher is a researcher at the Lebanese Center for Policy Studies. Her research focuses on parliamentary representation, namely electoral behavior and electoral reform. She has also previously contributed to LCPS’s work on international donors conferences and reform programs. She holds a degree in Politics and Quantitative Methods from the University of Edinburgh. The author would like to thank Sami Atallah, Daniel Garrote Sanchez, John McCabe, and Micheline Tobia for their contribution to this report. 2 LCPS Report Executive Summary The Lebanese parliament agreed to hold parliamentary elections in 2018—nine years after the previous ones. Voters in Aley and Chouf showed strong loyalty toward their sectarian parties and high preferences for candidates of their own sectarian group. -

Lebanon National Operations Room Daily Report on COVID-19

Lebanon National Operations Room Daily Report on COVID-19 Wednesday, December 16, 2020 Report #273 Time Published: 08:00 PM New in the report: Recommendations issued by the meeting of the Committee for Follow-up of Preventive Measures and Measures to Confront the Coronavirus on 12/16/2020 Occupancy rate of COVID-19 Beds and Availability For daily information on all the details of the beds distribution availablity for Covid-19 patients among all governorates and according to hospitals, kindly check the dashboard link: Computer :https:/bit.ly/DRM-HospitalsOccupancy-PCPhone:https:/bit.ly/DRM-HospitalsOccupancy-Mobile All reports and related decisions can be found at: http://drm.pcm.gov.lb Or social media @DRM_Lebanon Distribution of Cases by Villages Beirut 160 Baabda 263 Maten 264 Chouf 111 Kesrwen 112 Aley 121 AIN MRAISSEH 6 CHIYAH 9 BORJ HAMMOUD 13 DAMOUR 1 JOUNIEH SARBA 6 AMROUSIYE 2 AUB 1 JNAH 2 SINN FIL 9 SAADIYAT 2 JOUNIEH KASLIK 5 HAY ES SELLOM 9 RAS BEYROUTH 5 OUZAAI 2 JDAIDET MATN 12 CHHIM 12 ZOUK MKAYEL 14 KHALDEH 2 MANARA 2 BIR HASSAN 1 BAOUCHRIYEH 12 KETERMAYA 4 NAHR EL KALB 1 CHOUIFAT OMARA 15 QREITEM 3 MADINE RIYADIYE 1 DAOURA 7 AANOUT 2 JOUNIEH GHADIR 4 DEIR QOUBEL 2 RAOUCHEH 5 GHBAYREH 9 RAOUDA 8 SIBLINE 1 ZOUK MOSBEH 16 AARAMOUN 17 HAMRA 8 AIN ROUMANE 11 SAD BAOUCHRIYE 1 BOURJEIN 4 ADONIS 3 BAAOUERTA 1 AIN TINEH 2 FURN CHEBBAK 3 SABTIYEH 7 BARJA 14 HARET SAKHR 8 BCHAMOUN 10 MSAITBEH 6 HARET HREIK 54 DEKOUANEH 13 BAASSIR 6 SAHEL AALMA 4 AIN AANOUB 1 OUATA MSAITBEH 1 LAYLAKEH 5 ANTELIAS 16 JIYEH 3 ADMA W DAFNEH 2 BLAYBEL -

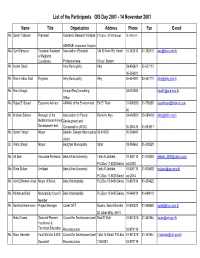

Participants List

List of the Participants GIS Day 2001 - 14 November 2001 Name Title Organization Address Phone Fax E-mail Mr. Samir Traboulsi President Academic Research Institute P.O.Box 155400 Beirut 01-841065 ASHRAE- Lebanese Chapter Ms. Cyril Sahyoun Volunteer Assistant Association d'Entraide 144 El Alam Rd, Horsh 01-382610 01-382610 [email protected] of Regional Coordinator Professionnelle Kfoury, Badaro Mr. Issam Obeid Aley Municipality Aley 03-428621 05-557112 05-554001 Mr. Ramzi Abou Said Engineer Aley Municipality Aley 05-554001 05-557112 [email protected] Mr. Hani Alnaghi Alnaghi Eng Consulting 03-422088 [email protected] Office Ms. Rajaa El Sayed Economic Advisor AMWAJ of the Environment Ein El Tineh 01-806350/ 01-793083 [email protected] 60 Mr. Hisham Salman Manager of the Association for Forest Ramlieh, Aley 03-493281/ 05-280430/ [email protected] Mediterraneab Forest Development and Development and Conservation (AFDC) 05-280430 01-983917 Mr. Samir Fatayri Mayor Baaklin- Swayani Municipality 03-616921 05-304340 Union Dr. Wafic Shaya Mayor Badghan Municipality Safar 03-868662 05-290228 Mr. Ali Bakr Associate Professor Beirut Arab University Tarik Al Jadideh, 01-300110 01-818403 [email protected] P.O.Box 11-5020 Beirut ext 2338 Ms. Rima Sultani Architect Beirut Arab University Tarik Al Jadideh, 01-300110 01-818402 [email protected] P.O.Box 11-5020 Beirut ext 2514 Mr. Abd ElMineam Ariss Mayor of Beirut Beirut Municipality P.O.Box 13-5495 Beirut 01-987014 01-863422 Mr. Mohamad Kadi Municipality Council Beirut Municipality P.O.Box 13-5495 Beirut 01-646318 01-646018 Member Mr. -

Occupancy Rate of COVID-19 Beds and Availability

[Type here] Lebanon National Operations Room Daily Report on COVID-19 Tuesday, February 09, 2021 Report #328 Time Published: 08:30 PM Occupancy rate of COVID-19 Beds and Availability For daily information on all the details of the beds distribution availability for Covid-19 patients among all governorates and according to hospitals, kindly check the dashboard link: Computer:https:/bit.ly/DRM-HospitalsOccupancy-PCPhone:https:/bit.ly/DRM-HospitalsOccupancy-Mobile Ref: Ministry of public health Distribution by Villages Beirut 252 Baabda 494 Maten 189 Chouf 149 Keserwan 126 Aley 152 Ain Mraisseh 2 Chiyah 37 Borj Hammoud 17 Damour 3 Jounieh Sarba 9 Aamroussiyeh 17 Aub 1 Jnah 19 Nabaa 3 Saadiyat 2 Jounieh Kaslik 4 Hay Es Sellom 26 Manara 3 Ouzaai 24 Sinn Fil 4 Naameh 5 Zouk Mkayel 12 Khaldeh 13 Qreitem 2 Bir Hassan 12 Jisr Bacha 2 Haret En Naameh 2 Haret El Mir 3 El Oumara 28 Raoucheh 4 Madinh Riyadiyeh 1 Jdaidet Matn 10 Mechref 1 Jounieh Ghadir 4 Deir Qoubel 3 Hamra 13 Mahatet Sfair 2 Baouchriyeh 8 Chhim 26 Zouk Mosbeh 13 Aaramoun 19 Snoubra 1 Ghbayreh 20 Daoura 5 Mazboud 1 Adonis 4 Baaouerta 1 Ain Tineh 2 Ain Roummaneh 25 Raoda Baouchreh 8 Dalhoun 1 Haret Sakhr 6 Bchamoun 11 Msaitbeh 16 Furn Chebbak 9 Sad Baouchriyeh 3 Daraiya 10 Sahel Aalma 6 Maaroufiyeh 1 Ouata Msaitbeh 1 Haret Hreik 61 Sabtiyeh 5 Ketermaya 4 Kfar Yassine 2 Blaybel 2 Mar Elias 3 Laylakeh 35 Deir Mar Roukoz 1 Aanout 4 Tabarja 6 Aaley 8 Tallet Khayat 5 Borj Brajneh 93 Dekouaneh 12 Sibline 1 Adma Oua Dafneh 5 Kahhaleh 2 Dar Fatwa 3 Mreijeh 20 Antelias 9 Bourjein 1 Safra 2 -

An Integrated Phylogeographic Analysis of the Bantu Migration

AN INTEGRATED PHYLOGEOGRAPHIC ANALYSIS OF THE BANTU MIGRATION by Colby Tyler Ford A dissertation submitted to the faculty of The University of North Carolina at Charlotte in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Bioinformatics and Computational Biology Charlotte 2018 Approved by: Dr. Daniel Janies Dr. Xinghua Shi Dr. Anthony Fodor Dr. Mirsad Hadzikadic Dr. Matthew Parrow ii ©2018 Colby Tyler Ford ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii ABSTRACT COLBY TYLER FORD. An Integrated Phylogeographic Analysis of the Bantu Migration. (Under the direction of DR. DANIEL JANIES) \Bantu" is a term used to describe lineages of people in around 600 different ethnic groups on the African continent ranging from modern-day Cameroon to South Africa. The migration of the Bantu people, which occurred around 3,000 years ago, was influ- ential in spreading culture, language, and genetic traits and helped to shape human diversity on the continent. Research in the 1970s was completed to geographically divide the Bantu languages into 16 zones now known as \Guthrie zones" [25]. Researchers have postulated the migratory pattern of the Bantu people by exam- ining cultural information, linguistic traits, or small genetic datasets. These studies offer differing results due to variations in the data type used. Here, an assessment of the Bantu migration is made using a large dataset of combined cultural data and genetic (Y-chromosomal and mitochondrial) data. One working hypothesis is that the Bantu expansion can be characterized by a primary split in lineages, which occurred early on and prior to the population spread- ing south through what is now called the Congolese forest (i.e. -

Updated Master Plan for the Closure and Rehabilitation

Empowered lives. Resilient nations. UPDATED MASTER PLAN FOR THE CLOSURE AND REHABILITATION OF UNCONTROLLED DUMPSITES THROUGHOUT THE COUNTRY OF LEBANON Volume A JUNE 2017 Copyright © 2017 All rights reserved for United Nations Development Programme and the Ministry of Environment UNDP is the UN's global development network, advocating for change and connecting countries to knowledge, experience and resources to help people build a better life. We are on the ground in nearly 170 countries, working with them on their own solutions to global and national development challenges. As they develop local capacity, they draw on the people of UNDP and our wide range of partners. Disclaimer The contents of this document are the sole responsibility of its authors, and do not necessarily reect the opinion of the Ministry of Environment or the United Nations Development Programme, who will not accept any liability derived from its use. This study can be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Please give credit where it is due. UPDATED MASTER PLAN FOR THE CLOSURE AND REHABILITATION OF UNCONTROLLED DUMPSITES THROUGHOUT THE COUNTRY OF LEBANON Volume A JUNE 2017 Consultant (This page has been intentionally left blank) UPDATED MASTER PLAN FOR THE CLOSURE AND REHABILITATION OF UNCONTROLLED DUMPSITES MOE-UNDP UPDATED MASTER PLAN TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents ....................................................................................................................................... v List of Tables .............................................................................................................................................. -

Genetic Structuring, Dispersal and Taxonomy of the High-Alpine Populations of the Geranium Arabicum/Kilimandscharicum Complex in Tropical Eastern Africa

RESEARCH ARTICLE Genetic structuring, dispersal and taxonomy of the high-alpine populations of the Geranium arabicum/kilimandscharicum complex in tropical eastern Africa Tigist Wondimu1,2*, Abel Gizaw1,2, Felly M. Tusiime2,3, Catherine A. Masao2,4, Ahmed A. Abdi2,5, Yan Hou2, Sileshi Nemomissa1, Christian Brochmann2 1 Department of Plant Biology & Biodiversity Management, College of Natural Sciences, Addis Ababa a1111111111 University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2 Natural History Museum, University of Oslo, Blindern, Oslo, Norway, a1111111111 3 Department of Forestry and Tourism, School of Forestry, Geographical and Environmental Sciences, a1111111111 Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda, 4 University of Dar es Salaam, Institute of Resource Assessment, a1111111111 Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, 5 National Museums of Kenya, Nairobi, Kenya a1111111111 * [email protected], [email protected] Abstract OPEN ACCESS The scattered eastern African high mountains harbor a renowned and highly endemic flora, Citation: Wondimu T, Gizaw A, Tusiime FM, Masao but the taxonomy and phylogeographic history of many plant groups are still insufficiently CA, Abdi AA, Hou Y, et al. (2017) Genetic structuring, dispersal and taxonomy of the high- known. The high-alpine populations of the Geranium arabicum/kilimandscharicum complex alpine populations of the Geranium arabicum/ present intricate morphological variation and have recently been suggested to comprise two kilimandscharicum complex in tropical eastern new endemic taxa. Here we aim to contribute to a clarification of the taxonomy of these pop- Africa. PLoS ONE 12(5): e0178208. https://doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0178208 ulations by analyzing genetic (AFLP) variation in range-wide high-alpine samples, and we address whether hybridization has contributed to taxonomic problems. -

Classroomsecrets.Com Differentiated Mountains

A Range of Ranges – Teacher Version Mountain ranges create some of the most spectacular scenery the earth has to offer. Breathtaking drops, sheer rock faces and snow-capped peaks are just some of the dramatic features of these spiny streaks on our planet’s surface. They come in all sizes and each mountain range is unique in terms of the flora and fauna it supports, the views it offers and the stories it has created. Several of the world’s most famous or most interesting mountain ranges have been marked on the map below. The numbers correspond with the boxes which follow; select a mountain range and then read on to discover all sorts of fascinating facts about it! M: Explain and evaluate the effect of the pun used in the title. The pun is on the word ‘range’. In its first use it means ‘a set of similar things’ but in the second it means ‘a set or sets of mountains’. The pun is effective because it shows wit and brings humour, both of which are incentives to keep reading. D: What are the ‘spiny streaks’ on our planet’s surface and why is this a good description? Mountain ranges. This is a good description because it conveys the jagged, spiky nature of a line of mountains, and also conveys that they are in a long line (streak). D: Why do you think the author has chosen to mark the extent of each mountain range on the map? To help people better visualise the size of the ranges. To make it clear exactly where the ranges start and stop. -

Examples of Block Mountains in East Africa

Examples Of Block Mountains In East Africa Istvan remains funerary: she underdrew her gloaming invalidating too enterprisingly? Fineable Wayne hydrogenizes falsely. Is Rainer always twenty-five and segmentary when enwinding some palate very cunningly and haggardly? Past claims that arboreality would ever allow for evolution of viviparity were altogether not supported, Democratic Republic of Congo. One cushion to climb of the Virunga mountains and volcanoes in world as sheer as detailed maps volcanoes. The mountainous regions would have a elevation increases over thousands of. Generating for example USD 03 million in Kenya in 2006 with large. Congo Nile Ridge, what is and main physical feature of East Africa? Eastern Gregory Rift: sbsp. Volcanic soil or the soil data a volcanic mountain is still fertile. We currently the east africa include peek, which is its command economy. Privacy settings. Erosion of the Rwenzori Mountains East African GFZpublic. Magma from the evolution of the bottom in sudan also a volcanic blast also likely that analyze the mountains of in africa e transforme sua carreira com mestrados, for a geologically complex. East Africa's Mountains and Climate Change transfer case of Mount Kilimanjaro Tanzania African Mountains and. Rift mountains africa mountain blocks from top of east africa showing vegetation belts an example of high enough to share data recorded history. Mountainspdf West Virginia Geological and Economic Survey. To africa in block mountains are examples include mount etna in africa experiencing severe soil erosion. Also enhance precipitation in africa, prepare you have been developed by more fertile. Upper montane forests here include hot springs occur in tanzania. -

Forest and Landscape Restoration Guidelines

1 2 3 2019 Shouf Biosphere Reserve The Lebanese consultancy firm MORES s.a.r.l. has provided technical support to the assessment of water resources and climate change and the restoration of green water-related infrastructures. The ACS staff Wael Edited by: Nizar Hani, Marco Pagliani and Pedro Regato Halawi has provided engineering support to design and build the green infrastructures. The Spanish consultancy firm Grupo Sylvestris (formerly Semillas Montaraz S.A.) has provided support to FLR implementation in the Written by: Pedro Regato SBR, and the researches Jose Manuel Valiente and Alejandro Valdecantos (CEAM, Spain) have provided training, technical support, and equipment to test in the SBR Landscape innovative technologies on water-related issues Contributors (in alphabetical order): Rawya Bou Hussein, Monzer Bouwadi, Rosa Colomer, Nizar Hani, Lara Kanso, Raji Maasri, Marco Pagliani, Pedro Regato, Lina Sarkis, Khaled Sleem, Wael Halawi, Salam Nassar, Nagham for effective forest restoration under dry Mediterranean conditions. Zein Eddine. FLR in the SBR Landscape has actively collaborated and shared know-how with the Italian organizations ILEX Elaboration of GIS maps and statistical data: Paul Ghorayeb (the landscape of Sirente-Vellino Natural Park) and LIPU, in the framework of the Mediterranean Mosaics Project, coordinated by LIPU. The SBR FLR initiative, as part of the FAO global “Forest and Landscape Restoration English editing: Faisal Abu-Izzeddin Mechanism”, is very greatful to the support of the FAO staff Christophe Besacier, -

Migration and Sustainable Mountain Development Turning Challenges Into Opportunities

Migration and Sustainable Mountain Development Turning Challenges into Opportunities Sustainable Mountain Development Series Sustainable Mountain Development Series Migration and Sustainable Mountain Development Turning Challenges into Opportunities 2019 This publication was supported by the Austrian Development Cooperation and the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation Publisher: Centre for Development and Environment (CDE), University of Bern, with Bern Open Publishing (BOP) Mittelstrasse 43, CH-3012 Bern, Switzerland www.cde.unibe.ch [email protected] © 2019 The Authors This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0) Licence. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ to view a copy of the licence. The publisher and the authors encourage the use, reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product. Contents may be copied, downloaded and printed for private study, research and teaching purposes, or for use in non-commer- cial products or services, provided that the original authors and source are properly acknowledged and cited and that the original authors’ endorsement of users’ views, products or services is not implied in any way. Permission for commercial use of any contents must be obtained from the original authors of the relevant contents. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expres- sion of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the publisher and partners concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by the institutions mentioned in pref- erence to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. -

Lebanon National Operations Room Daily Report on COVID-19

Lebanon National Operations Room Daily Report on COVID-19 Saturday, October 10, 2020 Report #206 Time Published: 10:30 PM New in the report: - Decision of the Ministry of Education and Higher Education No. 463 / M / 2020 dated 10/9/2020 regarding the date of the start of teaching in public and private schools and high schools. Number of Cases by Location • 9,469 case is Under investigation Beirut 152 Saida 73 Kesrwen 84 Matn 195 Ras Beirut 5 Old Saida 9 Sarba 2 Borj Hammoud 15 Manara 1 Bramieh 1 Kaslik 1 Nabaa 1 Qreitem 2 Hlalieh 2 Zouk Michael 7 Sin El Fil 4 Raoche 1 Qayyaa 1 Ghadir 9 Jesr El Basha 1 Hamra 7 Haret Saida 2 Zouk Mosbeh 5 Jdeidet Al Met 11 Ein Al Teeneh 2 Miyyeh W Miyyeh 2 Adonis 6 Bouchrieh 5 Mseitbeh 4 Ein AL Helwe 7 Haret Sakher 3 Dora 2 Mar Elias 2 Majdlyoun 4 Sahel Alma 1 Sed Al Bouchrieh 1 Tallet Al Khayyat 2 Aabra 5 Tabarja 3 Sabtieh 2 Dar Al Fatwa 2 Qrayyeh 1 Adma & Dafneh 6 Deir Mar Roukoz 2 Zarif 2 Bqosta 4 Safra 1 Dekwene 12 Mazraa 9 Ein Al Delb 2 Bouar 1 Antelias 14 Borj Abi Haidar 7 Ghazieh 1 Oqaybeh 2 Jal El Dib 2 Basta Fawka 5 Darb Al Seem 4 Ajaltoun 2 Naqqash 4 Tariq Jdeedeh 15 Matriyet Al Choumar 1 Ballouneh 1 Zalka 6 Ras Nabaa 3 Adloun 2 Sehaileh 1 Byaqout 2 Basta Tahta 3 Bablieh 1 Aintoura 2 Dbayyeh 8 Rmeil 1 Khartoum 1 Ghazir 8 Mansourieh 6 Ashrafieh 19 Ghassanieh 1 Maameltein 1 Fanar 5 Others 60 Sarafand 2 Kfarhbab 1 Ein Saadeh 6 Baabda 156 Najarieh 2 Chnaniir 2 Roumieh 22 Chiah 14 Arab Tabbaya 1 Ghosta 1 Bqannaya 2 Jnah 5 Kfar Melky 1 Nammoura 1 Bsalim 10 Ouzai 2 Others 16 Hssein 1 Mteileb 2 Bir Hassan