Making Overtures: Literature and Journalism, 1968 and 2011—A Dutch Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kritak DE SCHOOL VAN DE LITERATUUR

PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/104329 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2021-09-30 and may be subject to change. DE SCHOOL VAN DE LITERATUUR TOM LANOYE In. Ned Jos Joosten 16512 SUN· K rita k DE SCHOOL VAN DE LITERATUUR onder redactie van Eric Wagemans & Henk Peters Jos Joosten TOM LAN OYE De ontoereikendheid van het abstracte Paul Sars ADRIAAN VAM DIS De zandkastelen van je jeugd Omslagfoto voor de uitgave in eigen beheer Gent-Wevelgem-Gent, 1982 2 ^ ¿C 4 N O /óf "7 Jos Joosten T© M LANOYE De ontoereikendheid van het abstracte SUN · KRITAK 'V .'K M . ltsn- Het fotomateriaal is afkomstig uit de collectie van Tom Lanoye, Antwerpen Foto’s: Philip Boël, p. 63, 83 (rechts) - Willy Dé, Gent, p. 2,13 - Michiel Hendryckx, Gent, p. 33, 43, 57, 77 (rechts) - Fotoagentschap Luc Peeters, Lier, p. 92 - Gerrit Semé & partner, Amsterdam, p. 89 - Patrick de Spiegelaere, p. 49, 65, 77 (links) - Ben Wind, Rotterdam, p. 83 (links) Omslagontwerp en boekverzorging: Leo de Bruin, Amsterdam © Uitgeverij sun, Nijmegen 1996 ISBN 90 6168 4854 NUGI 321 Voor België Uitgeverij Kritak ISBN 90 6303 698 i D 1996 2393 45 EX UBRIS UNIVERStTATfê NOVIOMAGENSiS ínhoud 1. SLAGERSZOON MET DIVERSE BRILLEN Leven en literatuur 7 Middenstandsblues ? 8 Literaire leerschool 9 En publiceren maar 11 Maatschappelijke engagement 14 2. ‘we zijn a l l e e n en w e gaan k a p o t ’ Literatuur als ambacht 17 Lanoyes banale programma 18 Het banale banale 20 Afkeer van hoogdravendheid 20 De performer 23 De zin van het banale 24 De ontwikkeling van Lanoyes denken 28 3. -

New Dutch Fiction? Yes! It’S the New Title of the 10 Books from Holland Brochure We Have Been Publishing for More Than 20 Years

NEW DUTCH London Book Fair Issue Spring 2020 Dutch Foundation for Literature FICTION New Dutch Fiction? Yes! It’s the new title of the 10 Books From Holland brochure we have been publishing for more than 20 years. We changed the title to make clearer which genre of books we are promoting. Who decides the contents? Do you work together with Dutch publishers and agents? We want to showcase the best fiction from the Netherlands. We keep each other informed Most titles have been published about interest in titles and recently and have done very well rights sales. When we com- in terms of reviews, sales and mission a sample translation, awards or nominations. Equally we usually share the costs. important is the question: However, we always make our ‘Does it travel?’ Our specialists own decisions, and remain Barbara den Ouden, Victor completely independent. Schiferli, Tiziano Perez and Dick Broer try and keep up with How many books by one all the fiction that appears and author will you support? read as much as they can. As off this issue, we have worked with We can support three books by an advisory panel, who give us one author. If the author has advice and input on new fiction. changed foreign publishing The final selection is made house, previous titles are not by the Dutch Foundation for counted. Literature. Are all books in your brochure At book fairs, do you eligible for a grant? talk about these books exclusively? Yes they are, with a maximum subsidy of 100% of the trans- While we like to discuss our lation costs for classics and catalogue, there are always 70% for contemporary prose, other titles: books that have based on the actual fee paid by just appeared or are about to the publisher and capped at a come out or books that just maximum level of 10 eurocent missed our selection. -

ACF Regionals 2020 Packet O by the Editors Edited by Jinah Kim, Jordan

ACF Regionals 2020 Packet O by the Editors Edited by JinAh Kim, Jordan Brownstein, Geoffrey Chen, Taylor Harvey, Wonyoung Jang, Nick Jensen, Dennis Loo, Nitin Rao, and Neil Vinjamuri, with contributions from Billy Busse, Ophir Lifshitz, Tejas Raje, and Ryan Rosenberg Tossups 1. Voters in this state wrote “No Dams” on their ballot paper as part of a campaign to block the construction of the Franklin Dam. The flooding of this state’s Lake Pedder led to the formation of a “United Group” named for this state that became the world’s first green party. George Augustus Robinson arrived in this colony to “conciliate” a conflict between colonists and an indigenous group whose last surviving member was Truganini. This colony’s governor George Arthur ordered the formation of a human cordon to round up its indigenous inhabitants. John Howard instituted a mandatory buyback policy on long guns after 35 people died in this state’s Port Arthur Massacre. For 10 points, the Black War exterminated the aboriginal inhabitants of what Australian island? ANSWER: Tasmania <European History> 2. Schlenk and Brauns name a group of these molecules that exist as biradicals and are paramagnetic with a triplet ground state. The F number is correlated to the log of the retention factor in chromatography of these molecules. Clar’s rule is used to determine the most stable forms of these molecules. A process in which these molecules are broken down uses a system consisting of an alumina matrix, a silica binder, a kaolin filler, and a zeolite catalyst; that process is fluid catalytic cracking. -

Coming to Terms with the Past and Searching for an Identity: the Treatment of the Occupied Netherlands 179 Brother Alqng with Qther Hqstages

178 JOHN MICHIELSEN, BROCK UNIVERSITY i • I ; Coming to Terms With the Past and Searching for an Identity: II The Treatment of The Occupied Netherlands in the Fi<;tion of Hermans, Mulisch and Vestdijk / The popularity of Harry Mulisch's De had been somewhere else at a certain time aanslag, which was published in September things would have worked out differently. 1982, shows the constant interest that the This is especially the case in De aanslag and Dutch have had in literature dealing with the De donkere kamer. Pastorale 1943 concerns occupation of the Netherlands during World itself less with this question, perhaps because War Two. Simon Vestdijk's Pastorale 1943, it was written during and immediately after published in 1946, and Willem Frederik the occupation and its author's stay in prison. Hermans' De donkere kamer van Damokles of Vestdijk wished to render a vivid and realistic 1958 also deal with the same period. The three description of the lives of those who novels are interesting as a picture of the time; collaborated with the Germans, those who they concern themselves in part with the role worked for the underground, and those who of the resistance during the occupation and were hiding from the Germans. Even here, also the relationship between the occupied however, chance plays a role in what happens Dutch and the enemy. Naturally, the question to the characters. of guilt, both of the Germans and their collaborators the Dutch Nazis, arises in this As far as the structure of the novels is context. The three novels also present the concerned, De aanslag and De donkere kamer thesis that groups working against the enemy are the more complex novels of the three and were composed of bungling dilettantes, they are also the richest in symbols. -

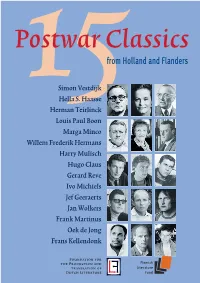

From Holland and Flanders

Postwar Classics from Holland and Flanders Simon Vestdijk 15Hella S. Haasse Herman Teirlinck Louis Paul Boon Marga Minco Willem Frederik Hermans Harry Mulisch Hugo Claus Gerard Reve Ivo Michiels Jef Geeraerts Jan Wolkers Frank Martinus Oek de Jong Frans Kellendonk Foundation for the Production and Translation of Dutch Literature 2 Tragedy of errors Simon Vestdijk Ivory Watchmen n Ivory Watchmen Simon Vestdijk chronicles the down- I2fall of a gifted secondary school student called Philip Corvage. The boy6–6who lives with an uncle who bullies and humiliates him6–6is popular among his teachers and fellow photo Collection Letterkundig Museum students, writes poems which show true promise, and delights in delivering fantastic monologues sprinkled with Simon Vestdijk (1898-1971) is regarded as one of the greatest Latin quotations. Dutch writers of the twentieth century. He attended But this ill-starred prodigy has a defect: the inside of his medical school but in 1932 he gave up medicine in favour of mouth is a disaster area, consisting of stumps of teeth and literature, going on to produce no fewer than 52 novels, as the jagged remains of molars, separated by gaps. In the end, well as poetry, essays on music and literature, and several this leads to the boy’s downfall, which is recounted almost works on philosophy. He is remembered mainly for his casually. It starts with a new teacher’s reference to a ‘mouth psychological, autobiographical and historical novels, a full of tombstones’ and ends with his drowning when the number of which6–6Terug tot Ina Damman (‘Back to Ina jealous husband of his uncle’s housekeeper pushes him into Damman’, 1934), De koperen tuin (The Garden where the a canal. -

The Language Use in and Reception of Ten Oorlog by Tom Lanoye and Luk

Ghent University Faculty of Arts and Philosophy CONTEMPORARY ADAPTATIONS OF SHAKESPEAREAN DRAMA: THE LANGUAGE USE IN AND RECEPTION OF TEN OORLOG BY TOM LANOYE AND LUK PERCEVAL Supervisor: Paper submitted in partial fulfilment of prof. dr. Sandro Jung the requirements for the degree of “Master in de Taal- en Letterkunde: Engels - Italiaans” by Inneke Plasschaert 2010 - 2011 Table of Contents 1. Acknowledgements 5 2. Introduction 6 3. A short history of BMCie and Ten Oorlog 7 3.1. The birth of BMCie 7 3.2. Perceval's master project: Ten Oorlog 11 4. Journalism and the reception of Ten Oorlog 14 4.1. Introduction 14 4.2. Journalism and Ten Oorlog 14 4.3. The academic response to Ten Oorlog 20 4.4. Ten Oorlog abroad: journalism and Schlachten! 23 4.5. Conclusion 24 5. The linguistic evolution in Ten Oorlog 26 5.1. An introduction to Ten Oorlog 26 5.2. Richaar Deuzième 29 5.2.1. Introduction: Shakespeare's Richard II 29 5.2.2. Internal language conflicts: Richaar 30 5.2.3. External language conflicts: Richaar, Bolingbroke, Jan van Gent, Northumberland, York 36 5.2.4. Conclusion 40 5.3. Hendrik Vier 42 5.3.1. Introduction: Shakespeare's Henry IV (part I & II) 42 5.3.2. Internal language conflicts: Hendrik Vier, La Falstaff 43 2 5.3.3. External language conflicts: Hendrik Vier, Roste, Westmoreland, La Falstaff, Henk 44 5.3.4. Conclusion 49 5.4. Hendrik de Vijfden 51 5.4.1. Introduction: Shakespeare's Henry V 51 5.4.2. Internal language conflicts: La Falstaff, Hendrik de Vijfden 51 5.4.3. -

A Prisoner's Conviction: Time, Space, and Morality in W.F. Hermans's The

A Prisoner’s Conviction: Time, Space, and Morality in W.F. Hermans’s The Darkroom of Damocles and Harry Mulisch’s The Assault Marc VAN ZOGGEL Huygens Instituut voor Nederlandse Geschiedenis Introduction: Time, Space, and the Prison Narrative In his landmark essay “Forms of Time and of the Chronotope in the Novel” (1938-1939), Russian literary critic Mikhail Bakhtin coined the concept of the ‘chronotope’ (literally, ‘time space’) in order to capture “the intrinsic connectedness of temporal and spatial relationships that are artistically expressed in literature” (Bakhtin 84). The chronotope, in other words, serves to describe the transformation of the physical notions of time and space into the artistic, i.e. literary categories of form and substance: In the literary artistic chronotope, spatial and temporal indicators are fused into one carefully thought-out, concrete whole. Time, as it were, thickens, takes on flesh, becomes artistically visible; likewise, space becomes charged and responsive to the movements of time, plot and history. This intersection of axes and fusion of indicators characterizes the artistic chronotope. (ibid.) Bakhtin envisages the chronotope as a central concept in what he calls the discipline of ‘historical poetics’. For example, in his discussion of ancient Greek romances – semi- historical adventure stories – Bakhtin shows how prison scenes are instrumental in the deceleration and freezing of plot movement: “Captivity and prison presume guarding and isolating the hero in a definite spot in space, impeding his subsequent spatial movement toward his goal, that is, his subsequent pursuits and searches and so forth” (Bakhtin 99; italics in original). The prison thus plays a vital role in the semi-fictional biographies presented in these stories. -

Willem Frederik Hermans Het Behouden Huis (1951)

Willem Frederik Hermans (1921-1995) Het behouden huis (1951) Vragen en opdrachten Inhoud Willem Frederik Hermans (1921-1995) 3 Het behouden huis (1951) 5 De Grote Drie (Hermans, Reve en Mulisch) 7 Vragen en opdrachten 10 Verder lezen 13 Bronnen 14 2 Willem Frederik Hermans (1921-1995) Willem Frederik Hermans werd in 1921 geboren in Amsterdam in een onderwijzersgezin. Aan het begin van de oorlog pleegde zijn zus zelfmoord; dat was een grote schok voor Hermans. Na het afronden van het gymnasium ging hij fysische geografie studeren. Hij promoveerde cum laude in 1955 en werkte tot 1973 aan de universiteit van Groningen. Daarna ging hij in Parijs en later nog in Brussel wonen. Hermans schreef romans, verhalen, gedichten, toneelstukken en essays. Zijn bekendste boeken zijn De donkere kamer van Damokles (1958) en Nooit meer slapen (1966). In 1947 verscheen zijn debuutroman De tranen der acacia’s en vele lezers vonden het een schokkend boek. In de personages van dit boek zag men een door de oorlog getekende generatie zonder hoop, geloof en idealen. De hoofdpersonen bedriegen elkaar, zijn wanhopig en hebben geen grenzen in hun seksuele omgang. Bovendien liet Hermans in het boek zien dat het Nederlands verzet tegen de Duitsers niet altijd even heldhaftig was. De personages in de wereld van Hermans proberen greep te krijgen op de wereld, maar dat is altijd tevergeefs. Uiteindelijk zijn ze gedesillusioneerd, ontgoocheld. Hermans noemt zichzelf ook ‘misantroop’ (iemand die mensen haat) en hij komt ook in interviews erg cynisch over. Hermans stond wel bekend als de meest gevreesde schrijver van Nederland, als de kwelgeest van de literatuur. -

Rory's List (In Alphabetical Order)

Rory's List (in alphabetical order) 1984 by George Orwell The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain Alice in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll (TBR) The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay by Michael Chabon An American Tragedy by Theodore Dreiser Angela's Ashes by Frank McCourt Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy Anne Frank: The Diary of a Young Girl by Anne Frank Archidamian War by Donald Kagan The Art of Fiction by Henry James The Art of War by Sun Tzu As I Lay Dying by William Faulkner Atonement by Ian McEwan Autobiography of a Face by Lucy Grealy The Awakening by Kate Chopin Babe by Dick King-Smith Backlash: The Undeclared War Against American Women by Susan Faludi Balzac and the Little Chinese Seamstress by Dai Sijie Bel Canto by Ann Patchett The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath (TBR) Beloved by Toni Morrison Beowulf: A New Verse Translation by Seamus Heaney The Bhagava Gita The Bielski Brothers: The True Story of Three Men Who Defied the Nazis, Built a Village in the Forest, and Saved 1,200 Jews by Peter Duffy Bitch in Praise of Difficult Women by Elizabeth Wurtzel A Bolt from the Blue and Other Essays by Mary McCarthy Brave New World by Aldous Huxley Brick Lane by Monica Ali Bridgadoon by Alan Jay Lerner Candide by Voltaire The Canterbury Tales by Chaucer Carrie by Stephen King Catch-22 by Joseph Heller The Catcher in the Rye by J. D. Salinger Charlotte's Web by E. B. White The Children's Hour by Lillian Hellman Christine by Stephen King A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens A Clockwork Orange by Anthony Burgess The Code of the Woosters by P.G. -

181284Pub.Pdf

PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/181284 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2021-09-29 and may be subject to change. Review Edwin Praat, Verrek, het is geen kunstenaar. Gerard Reve en het schrijverschap (Amsterdam: AUP, 2014) Sander Bax, De Mulisch Mythe. Harry Mulisch: schrijver, intellectueel, icoon (Amsterdam: Meulenhoff, 2015) Daan Rutten, De ernst van het spel. Willem Frederik Hermans en de ethiek van de persoonlijke mythologie (Hilversum: Verloren, 2016) Roel Smeets, Radboud University Nijmegen Every national literary field has its darlings and this is true for Dutch literature as well. After the Second World War, an obsession emerged with three writers that have been referred to as the ‘Great Three’: Harry Mulisch (1927-2010), Gerard Reve (1923-2006) and Willem Frederik Hermans (1921-1995). For decades, Simon Vestdijk (1898-1971) was considered to be the nestor of Dutch literature, yet with his death emerged the need for new grand names.1 Mulisch, Reve and Hermans were coined as the Great Three in the 1970s, and their reputation has been reiterated time and again and consolidated by critics as well as in literary histories and schoolbooks. A widespread attention for these three post-World War II writers was set, both in- and outside the walls of academia, and the recent publication of three major studies attest to the continued interest for their work. Sander Bax’s De Mulisch Mythe. -

Postmodern’ Relativism Thomas Vaessens, University of Amsterdam

Dutch Novelists Beyond ‘Postmodern’ Relativism Thomas Vaessens, University of Amsterdam Abstract: In this article I will show how Dutch authors reoriented themselves from the late 1980s onwards in relation to the postmodern tradition they inherited. I will discuss the critique of postmodernism formulated by Dutch writers in the light of the following hypothesis. A new, late postmodern position has gradually emerged from the Dutch debate about literature and its function. The authors in question consider (literary) postmodernism as a necessary but insufficient counter-reaction against liberal humanism and its self-assured conception of literature. The question that therefore arises is what, if anything, can be saved in terms of values such as sincerity, authenticity, originality and truth, when postmodernism has succeeded in hedging these modern and pre-eminently literary values with suspicion. Can they be reclaimed for literature without returning to their old, essentialist, rationalistic and humanistic underpinnings? Postmodernism is now seen as a medicine against the liberal humanist conception of culture, a medicine which, in the course of the eighties and nineties, revealed unpleasant side effects, such as relativism, cynicism and noncommittal irony. I will try to explain the tendency towards engagement in Dutch novels, not as a late-in- the-day rejection of postmodernism, but as a reaction to its side effects. Keywords: (Late) Postmodernism, Contemporary Dutch Literature, The Novel, Relativism, Engagement, Devaluation of Literature, Reality Hunger Introduction: the Demise of (International) Postmodernism Now that we have reached the point at which postmodernism, rightly or wrongly, has been declared moribund, it is time to assess its literary legacy critically. -

The Neurocognitive Basis of Feature Integration Keizer, A.W

The neurocognitive basis of feature integration Keizer, A.W. Citation Keizer, A. W. (2010, February 18). The neurocognitive basis of feature integration. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/14752 Version: Not Applicable (or Unknown) Licence agreement concerning inclusion of doctoral thesis in the License: Institutional Repository of the University of Leiden Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/14752 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). The Neurocognitive Basis of Feature Integration André W. Keizer ISBN 978-90-9025120-2 Copyright © 2010, André W Keizer Printed by Print Partners Ipskamp B.V. Amsterdam All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronically, mechanically, by photocopy, by recording, or otherwise, without prior permission from the author. The Neurocognitive Basis of Feature Integration Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van Doctor aan de Universiteit Leiden, op gezag van Rector Magnificus prof. mr. P.F. van der Heijden, volgens besluit van het College voor Promoties te verdedigen op donderdag 18 februari 2010 klokke 16.15 uur door André Willem Keizer geboren te Leeuwarden in 1980 Promotiecommissie Promotor Prof. dr. B. Hommel Overige leden Prof. dr. P. Roelfsema (University of Amsterdam) Prof. dr. E. Crone Prof. dr. N. O. Schiller Dr. S. Nieuwenhuis Dr. G. P. H. Band “Zoals je met een lens de achtergrond onscherp kunt draaien, zo kun je ervoor zorgen