The Language Use in and Reception of Ten Oorlog by Tom Lanoye and Luk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Dull Soldier and a Keen Guest: Stumbling Through the Falstaffiad One Drink at a Time

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2017 A Dull Soldier and a Keen Guest: Stumbling Through The Falstaffiad One Drink at a Time Emma Givens Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the Dramatic Literature, Criticism and Theory Commons, and the Theatre History Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/4826 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Emma Givens 2017 All rights reserved A Dull Soldier and a Keen Guest: Stumbling Through The Falstaffiad One Drink at a Time A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts at Virginia Commonwealth University. Emma Pedersen Givens Director: Noreen C. Barnes, Ph.D. Director of Graduate Studies Department of Theatre Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia March, 2017 ii Acknowledgement Theatre is a collaborative art, and so, apparently, is thesis writing. First and foremost, I would like to thank my grandmother, Carol Pedersen, or as I like to call her, the world’s greatest research assistant. Without her vast knowledge of everything Shakespeare, I would have floundered much longer. Thank you to my mother and grad-school classmate, Boomie Pedersen, for her unending support, my friend, Casey Polczynski, for being a great cheerleader, my roommate, Amanda Long for not saying anything about all the books littered about our house and my partner in theatre for listening to me talk nonstop about Shakespeare over fishboards. -

Kritak DE SCHOOL VAN DE LITERATUUR

PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/104329 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2021-09-30 and may be subject to change. DE SCHOOL VAN DE LITERATUUR TOM LANOYE In. Ned Jos Joosten 16512 SUN· K rita k DE SCHOOL VAN DE LITERATUUR onder redactie van Eric Wagemans & Henk Peters Jos Joosten TOM LAN OYE De ontoereikendheid van het abstracte Paul Sars ADRIAAN VAM DIS De zandkastelen van je jeugd Omslagfoto voor de uitgave in eigen beheer Gent-Wevelgem-Gent, 1982 2 ^ ¿C 4 N O /óf "7 Jos Joosten T© M LANOYE De ontoereikendheid van het abstracte SUN · KRITAK 'V .'K M . ltsn- Het fotomateriaal is afkomstig uit de collectie van Tom Lanoye, Antwerpen Foto’s: Philip Boël, p. 63, 83 (rechts) - Willy Dé, Gent, p. 2,13 - Michiel Hendryckx, Gent, p. 33, 43, 57, 77 (rechts) - Fotoagentschap Luc Peeters, Lier, p. 92 - Gerrit Semé & partner, Amsterdam, p. 89 - Patrick de Spiegelaere, p. 49, 65, 77 (links) - Ben Wind, Rotterdam, p. 83 (links) Omslagontwerp en boekverzorging: Leo de Bruin, Amsterdam © Uitgeverij sun, Nijmegen 1996 ISBN 90 6168 4854 NUGI 321 Voor België Uitgeverij Kritak ISBN 90 6303 698 i D 1996 2393 45 EX UBRIS UNIVERStTATfê NOVIOMAGENSiS ínhoud 1. SLAGERSZOON MET DIVERSE BRILLEN Leven en literatuur 7 Middenstandsblues ? 8 Literaire leerschool 9 En publiceren maar 11 Maatschappelijke engagement 14 2. ‘we zijn a l l e e n en w e gaan k a p o t ’ Literatuur als ambacht 17 Lanoyes banale programma 18 Het banale banale 20 Afkeer van hoogdravendheid 20 De performer 23 De zin van het banale 24 De ontwikkeling van Lanoyes denken 28 3. -

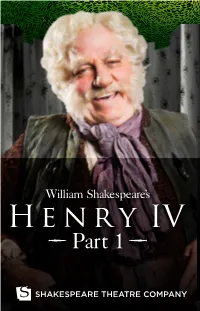

Henry Iv, Parts One &

HENRY IV, PARTS ONE & TWO by William Shakespeare Taken together, Shakespeare's major history plays cover the 30-year War of the Roses, a struggle between two great families, descended from King Edward III, for the throne of England. The division begins in “Richard II,” when that king, of the House of York, is deposed by Henry Bolingbroke of the House of Lancaster, who will become Henry IV. The two Henry IV plays take us through this king's reign, ending with the coronation of his ne'er-do-well son, Prince Hal, as Henry V. In subsequent plays, we follow the fortunes of these two families as first one, then the other, assumes the throne, culminating in “Richard III,” which ends with the victory of Henry VII, who ends the War of the Roses by combining both royal lines into the House of Tudor and ruthlessly killing off all claimants to the throne. What gives the Henry IV plays their great appeal is the presence of a fat, rascally knight named Falstaff, with whom Prince Hal spends his youth. Falstaff is one of Shakespeare's most memorable characters and his comedy tends to dominate the action. He was so popular with audiences that Shakespeare had to kill him off in “Henry V,” lest he detract from the heroism of young King Henry V. “Henry IV, Part One,” deals with a rebellion against King Henry by his former allies. The subplot concerns the idle life led by the heir to the throne, Prince Hal, who spends his time with London's riffraff, even going so far as to join them in robbery. -

Masaryk University Faculty of Education

Masaryk University Faculty of Education Department of English Language and Literature We, Band of Brothers in Arms Friendship and Violence in Henry V by William Shakespeare Bachelor thesis Brno 2016 Supervisor: Author: Mgr. Jaroslav Izavčuk Vladimír Ovčáček Prohlašuji, že jsem bakalářskou práci na téma ‘We, Band of Brothers in Arms - Friendship and Violence in Henry V by William Shakespeare’ vypracoval samostatně, s využitím pouze citovaných pramenů, dalších informací a zdrojů v souladu s Disciplinárním řádem pro studenty Pedagogické fakulty Masarykovy univerzity a se zákonem č. 121/2000 Sb., o právu autorském, o právech souvisejících s právem autorským a o změně některých zákonů (autorský zákon), ve znění pozdějších předpisů. Souhlasím, aby práce byla uložena na Masarykově univerzitě v Brně v knihovně Pedagogické fakulty a zpřístupněna ke studijním účelům. V Brně dne………………………….. Podpis………………………………. - 1 - I would like to express my gratitude to my parents and friends, without whose support I would never have a chance to reach this important point of my life. I would also like to thank Mgr. Jaroslav Izavčuk for his kind support, helpful advice, and patience. - 2 - Anotace Tato bakalářská práce analyzuje hru Jindřich V. od Wiliama Shakespeara, a to z hlediska násilí a přátelství, jakožto témat často se objevujících v této hře. Bakalářská práce je tvořena teoretickou a praktickou částí. V teoretické části je popsán děj hry a jsou zde také určeny cíle této práce. Dále jsou zde charakterizovány termíny násilí a přátelství a popsán způsob jakým bylo v renesančním dramatu vnímáno násilí. Dále jsem zde vytvořil hypotézu a definoval metody výzkumu. Na konci teoretické části je stručný popis historického kontextu, do kterého je tato hra včleněna. -

King and Country: Shakespeare’S Great Cycle of Kings Richard II • Henry IV Part I Henry IV Part II • Henry V Royal Shakespeare Company

2016 BAM Winter/Spring #KingandCountry Brooklyn Academy of Music Alan H. Fishman, Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board BAM, the Royal Shakespeare Company, and Adam E. Max, Vice Chairman of the Board The Ohio State University present Katy Clark, President Joseph V. Melillo, Executive Producer King and Country: Shakespeare’s Great Cycle of Kings Richard II • Henry IV Part I Henry IV Part II • Henry V Royal Shakespeare Company BAM Harvey Theater Mar 24—May 1 Season Sponsor: Directed by Gregory Doran Set design by Stephen Brimson Lewis Global Tour Premier Partner Lighting design by Tim Mitchell Music by Paul Englishby Leadership support for King and Country Sound design by Martin Slavin provided by the Jerome L. Greene Foundation. Movement by Michael Ashcroft Fights by Terry King Major support for Henry V provided by Mark Pigott KBE. Major support provided by Alan Jones & Ashley Garrett; Frederick Iseman; Katheryn C. Patterson & Thomas L. Kempner Jr.; and Jewish Communal Fund. Additional support provided by Mercedes T. Bass; and Robert & Teresa Lindsay. #KingandCountry Royal Shakespeare Company King and Country: Shakespeare’s Great Cycle of Kings BAM Harvey Theater RICHARD II—Mar 24, Apr 1, 5, 8, 12, 14, 19, 26 & 29 at 7:30pm; Apr 17 at 3pm HENRY IV PART I—Mar 26, Apr 6, 15 & 20 at 7:30pm; Apr 2, 9, 23, 27 & 30 at 2pm HENRY IV PART II—Mar 28, Apr 2, 7, 9, 21, 23, 27 & 30 at 7:30pm; Apr 16 at 2pm HENRY V—Mar 31, Apr 13, 16, 22 & 28 at 7:30pm; Apr 3, 10, 24 & May 1 at 3pm ADDITIONAL CREATIVE TEAM Company Voice -

Program from the Production

STC Board of Trustees Board of Trustees Stephen A. Hopkins Emeritus Trustees Michael R. Klein, Chair Lawrence A. Hough R. Robert Linowes*, Robert E. Falb, Vice Chair W. Mike House Founding Chairman John Hill, Treasurer Jerry J. Jasinowski James B. Adler Pauline Schneider, Secretary Norman D. Jemal Heidi L. Berry* Michael Kahn, Artistic Director Scott Kaufmann David A. Brody* Kevin Kolevar Melvin S. Cohen* Trustees Abbe D. Lowell Ralph P. Davidson Nicholas W. Allard Bernard F. McKay James F. Fitzpatrick Ashley M. Allen Eleanor Merrill Dr. Sidney Harman* Stephen E. Allis Melissa A. Moss Lady Manning Anita M. Antenucci Robert S. Osborne Kathleen Matthews Jeffrey D. Bauman Stephen M. Ryan William F. McSweeny Afsaneh Beschloss K. Stuart Shea V. Sue Molina William C. Bodie George P. Stamas Walter Pincus Landon Butler Lady Westmacott Eden Rafshoon Dr. Paul Carter Rob Wilder Emily Malino Scheuer* Chelsea Clinton Suzanne S. Youngkin Lady Sheinwald Dr. Mark Epstein Mrs. Louis Sullivan Andrew C. Florance Ex-Officio Daniel W. Toohey Dr. Natwar Gandhi Chris Jennings, Sarah Valente Miles Gilburne Managing Director Lady Wright Barbara Harman John R. Hauge * Deceased 3 Dear Friend, Table of Contents I am often asked to choose my favorite Shakespeare play, and Henry IV, Parts 1 and 2 Title Page 5 it is very easy for me to answer immediately Henry IV, Parts 1 The Play of History and 2. In my opinion, there is by Drew Lichtenberg 6 no other play in the English Synopsis: Henry IV, Part 1 9 language which so completely captures the complexity and Synopsis: Henry IV, Part 2 10 diversity of an entire world. -

Orson Welles: CHIMES at MIDNIGHT (1965), 115 Min

October 18, 2016 (XXXIII:8) Orson Welles: CHIMES AT MIDNIGHT (1965), 115 min. Directed by Orson Welles Written by William Shakespeare (plays), Raphael Holinshed (book), Orson Welles (screenplay) Produced by Ángel Escolano, Emiliano Piedra, Harry Saltzman Music Angelo Francesco Lavagnino Cinematography Edmond Richard Film Editing Elena Jaumandreu , Frederick Muller, Peter Parasheles Production Design Mariano Erdoiza Set Decoration José Antonio de la Guerra Costume Design Orson Welles Cast Orson Welles…Falstaff Jeanne Moreau…Doll Tearsheet Worlds" panicked thousands of listeners. His made his Margaret Rutherford…Mistress Quickly first film Citizen Kane (1941), which tops nearly all lists John Gielgud ... Henry IV of the world's greatest films, when he was only 25. Marina Vlady ... Kate Percy Despite his reputation as an actor and master filmmaker, Walter Chiari ... Mr. Silence he maintained his memberships in the International Michael Aldridge ...Pistol Brotherhood of Magicians and the Society of American Tony Beckley ... Ned Poins and regularly practiced sleight-of-hand magic in case his Jeremy Rowe ... Prince John career came to an abrupt end. Welles occasionally Alan Webb ... Shallow performed at the annual conventions of each organization, Fernando Rey ... Worcester and was considered by fellow magicians to be extremely Keith Baxter...Prince Hal accomplished. Laurence Olivier had wanted to cast him as Norman Rodway ... Henry 'Hotspur' Percy Buckingham in Richard III (1955), his film of William José Nieto ... Northumberland Shakespeare's play "Richard III", but gave the role to Andrew Faulds ... Westmoreland Ralph Richardson, his oldest friend, because Richardson Patrick Bedford ... Bardolph (as Paddy Bedford) wanted it. In his autobiography, Olivier says he wishes he Beatrice Welles .. -

Shakespeare's Souls with Longing

Digital Commons @ Assumption University Political Science Department Faculty Works Political Science Department 2011 Shakespeare's Souls with Longing Bernard J. Dobski Assumption College, [email protected] Dustin A. Gish College of the Holy Cross Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.assumption.edu/political-science-faculty Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Dobski, Bernard J. and Dustin A. Gish. "Shakespeare's Souls with Longing." Souls With Longing: Representations of Honor and Love in Shakespeare. Edited by Bernard J. Dobski and Dustin A. Gish. Lexington Books, 2011. Pages 3-18. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Political Science Department at Digital Commons @ Assumption University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Political Science Department Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Assumption University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Shakespeare’s Souls with Longing Bernard J. Dobski and Dustin A. Gish We discover in the works of William Shakespeare the wisdom of a poet whose art charms and entertains, even as it educates us. In the “eternal lines” of his plays and poetry, Shakespeare conjures a vivid gallery of characters for his audience and readers.1 His representations of human beings are as true to life as any nature has conceived, perhaps more true. We may wonder if there is a Falstaff or a Hamlet or a Cleopatra living in our midst from whom we can learn as much as we can from the characters that inhabit Shakespeare’s works. Through sustained reflection on his characters, we become keenly aware of our humanity and thus come to know ourselves more profoundly. -

ORSON WELLES As FALSTAFF in CHIMES at MIDNIGHT

ORSON WELLES AS FALSTAFF IN CHIMES AT MIDNIGHT “ If I wanted to get into heaven on the basis of one movie, that’s the one I would offer up. I think it’s because it is, to me, the least flawed . I succeeded more completely, in my view, with that than with anything else.” —Orson Welles “Chimes at Midnight . may be the greatest Shakespearean film ever made, bar none.” —Vincent Canby, The New York Times “ He has directed a sequence, the Battle of Shrewsbury, which is unlike anything he has ever done, indeed unlike any battle ever done on the screen before. It ranks with the best of Griffith, John Ford, Eisenstein, Kurosawa—that is, with the best ever done.” —Pauline Kael Spain • 1966 • 116 Minutes • Black & White • 1.66:1 Booking Inquiries: Janus Films Press Contact: Ryan Werner [email protected] • 212-756-8761 [email protected] • 917-254-7653 CHIMES AT MIDNIGHT JANUS FILMS SYNOPSIS The crowning achievement of Orson Welles’s later film career,Chimes at Midnight returns to the screen after being unavailable for decades. This brilliantly crafted Shakespeare adaptation was the culmination of Welles’s lifelong obsession with the Bard’s ultimate rapscallion, Sir John Falstaff, the loyal, often soused childhood friend to King Henry IV’s wayward son Prince Hal. Appearing in several plays as a comic supporting figure, Falstaff is here the main event: a robustly funny and ultimately tragic screen antihero played by Welles with towering, lumbering grace. Integrating elements from both Henry IV plays as well as Richard II, Henry V, and The Merry Wives of Windsor, Welles created an unorthodox Shakespeare film that is also a gritty period piece, which he called “a lament . -

BRSP Henry Ivs 2015

Henry IV, Parts I & II By William Shakespeare Cutting by BRSP & Hannah Todd ACT 1 Scene 2 Enter Prince of Wales, and Sir John Falstaff. [And Mistress Quickly and Doll] FALSTAFF Now, Hal, what time of day is it, lad? PRINCE What a devil hast thou to do with the time of the day? Unless hours were cups of sack, and minutes capons, and clocks the tongues of bawds, I see no reason why thou shouldst be so superfluous to demand the time of the day. FALSTAFF Indeed, you come near me now, Hal. And I prithee, sweet wag, when thou art king, as God save thy Grace—Majesty, I should say, for grace thou wilt have none— PRINCE What, none? FALSTAFF No, by my troth, not so much as will serve to be prologue to an egg and butter. PRINCE Well, how then? Come, roundly, roundly. FALSTAFF Marry then, sweet wag, I prithee, shall there be gallows standing in England when thou art king? Do not when thou art king, hang a thief. PRINCE No, thou shalt. FALSTAFF Shall I? O rare! By the Lord, I’ll be a brave judge. PRINCE Thou judgest false already. I mean thou shalt have the hanging of the thieves, and so become a rare hangman. FALSTAFF Well, Hal, well, and in some sort it jumps with my humor as well as waiting in the court, I can tell you. O, thou art indeed able to corrupt a saint. Thou hast done much harm upon me, Hal, God forgive thee for it. Before I knew thee, Hal, I knew nothing, and now am I, if a man should speak truly, little better than one of the wicked. -

Belgium at a Glance

Belgium at a glance Belgium – a bird's eye view Belgium, a country of regions ................................................................ 5 A constitutional and hereditary monarchy .............................................6 A country full of creative talent ............................................................. 7 A dynamic economy ...............................................................................8 Treasure trove of contrasts ...................................................................8 Amazing history! ....................................................................................9 The advent of the state reform and two World Wars ........................... 10 Six state reforms ...................................................................................11 Working in Belgium An open economy .................................................................................13 Flexibility, quality and innovation ..........................................................13 A key logistics country ......................................................................... 14 Scientific research and education .........................................................15 Belgium – a way of life A gourmet experience ...........................................................................17 Fashion, too, is a Belgian tradition ...................................................... 18 Leading-edge design ............................................................................ 19 Folklore and traditions -

'Ieder Zijn Claus' LETTERENHUIS: Felix Poetry Festival – Alsof Er Te

Clausjaar 2018 Claus wordt in 2018 uitgebreid herdacht met een gevarieerd programma met tentoonstellingen en voorstellingen door verschillende instellingen, zoals o.a. Het Letterenhuis, Maurice Verbaet Center, BOZAR, Cinema Zuid, Vereniging van Antwerpse Bibliofielen, DE Studio, Antiquariaat De Slegte, Behoud de Begeerte, deBuren, KVS, CINEMATEK, Muntpunt, Passa Porta… Een overzicht van het programma vindt u op de website van het Letterenhuis. LETTERENHUIS: Letterenhuisfestival – ‘Ieder zijn Claus’ Zaterdag 5 mei 2018, van 14u tot 18u – 20 locaties. De tweede editie van het Letterenhuisfestival staat helemaal in het teken van Hugo Claus. Voor de expo ‘Hugo Claus. Achter vele maskers’ in het Letterenhuis koos curator Hilde Van Mieghem ervoor om de meester zelf aan het woord te laten. Voor het festival laten we graag kenners en bewonderaars aan het woord over Claus en vragen we auteurs, acteurs en muzikanten om de teksten van Claus te laten weerklinken. Het Letterenhuis sprak samen met het Stadsmagazijn bijna 20 locaties in de buurt aan om een Claus-programma te aan te bieden. In het Letterenhuis interviewt Marcel Vanthilt literaire gasten over de verschillende facetten van de persoon Claus, waaronder Patrick Conrad over Claus als regisseur, Suzanne Rethans over Claus en Sylvia Kristel en Luc Coorevits over Claus als performer. Er zijn in het Letterenhuis ook korte depotrondleidingen en een snelcursus ‘Claus voor beginners’. In het Stadsmagazijn is er o.a. muziek van Bert Ostyn (van Absynthe Minded), slam poetry en een kleine boekenmarkt. Een greep uit het programma op locatie: Bernard Dewulf, Maud Vanhauwaert, Vitalski, Peter Holvoet-Hanssen, Yannick Dangre, Lotte Dodion en Tom Dewispelaere lezen Claus, Patricia Beysens zingt Claus, Robbe De Hert bespreekt de films van Claus, foto’s van Herman Selleslags en tekeningen van Cordelia, Katrin Lohmann maakt met gedetineerden een podcastuitzending van Radio Begijnenstraat met teksten van Claus, en er is tenslotte een voorleesmarathon waaraan u ook zelf kunt deelnemen.