Pennsylvania Magazine of HISTORY and BIOGRAPHY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charles Roberts Autograph Letters Collection MC.100

Charles Roberts Autograph Letters collection MC.100 Last updated on January 06, 2021. Haverford College Quaker & Special Collections Charles Roberts Autograph Letters collection Table of Contents Summary Information....................................................................................................................................7 Administrative Information........................................................................................................................... 7 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................7 Collection Inventory...................................................................................................................................... 9 110.American poets................................................................................................................................. 9 115.British poets.................................................................................................................................... 16 120.Dramatists........................................................................................................................................23 130.American prose writers...................................................................................................................25 135.British Prose Writers...................................................................................................................... 33 140.American -

Knight Templar Magazine

Grand Master's Message for February 2004 February brings many pleasant and yet poignant memories. It is, of course, the month in which we remember those dear to us with Valentine's Day (another day of love). We are so fortunate to have those ladies in our lives who have done so much for us; our wives, mothers, sisters, daughters, etc. Speaking for the Sir Knights, we do appreciate everything that you have done for us. Many of our ladies are members of the Social Order of the Beauceant, which has raised tens of thousands of dollars, annually, for the Knights Templar Eye Foundation. Some states do not have the S.O.O.B. but do have ladies' auxiliaries, which also help their Commanderies and the Eye Foundation. Sir Knights, be sure that you recognize and thank your ladies. Some roses, candy, or whatever makes her happy would be good. She will probably wonder, what the devil you have been doing to cause you to take this action, but the net result should be good. This February is in a "Leap Year," which reminds me of a dear aunt who was born on February 29. When she passed away, she had celebrated 21 birthdays. She was my mother's next older sister and was a true workaholic. She loved to fish and would catch fish no matter what it took to catch them. Happy Birthday, Aunt Lenora! Another February memory was the tradition at our house of pruning our rose bushes on or around Valentine's Day. This was at a time when the bush was dormant and pruning would have the best effect on the bush as it came to life and began growing again in the spring. -

Selected Peale Family Papers

Selected Peale family papers Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 2 Container Listing ...................................................................................................... Selected Peale family papers AAA.pealpeal Collection Overview Repository: Archives of American Art Title: Selected Peale family papers Identifier: AAA.pealpeal Date: 1803-1854 Creator: Peale family Extent: 3 Microfilm reels (3 partial microfilm reels) Language: English . Administrative Information Acquisition Information Microfilmed by the Historical Society of Pennsylvania for the Archives of American Art, 1955. Location of Originals REEL P21: Originals in the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Peale family papers. Location of Originals REEL P23, P29: Originals in the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, -

From Useful Knowledge to Rational Amusement: Museums in Early America

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 5-2004 From Useful Knowledge to Rational Amusement: Museums in Early America Allison M. Morrill University of Tennessee, Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Morrill, Allison M., "From Useful Knowledge to Rational Amusement: Museums in Early America. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2004. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/4690 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Allison M. Morrill entitled "From Useful Knowledge to Rational Amusement: Museums in Early America." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in History. Lorri Glover, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: J.P. Dessel, G. Kurt Piehler Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Allison M. Morrillentitled "From Useful Knowledge to Rational Amusement: Museums in EarlyAmerica." I have examined the finalpaper copy of this thesis for formand content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillmentof the requirements forthe degreeof Master of Arts, with a major in History. -

“The Humble, Though More Profitable Art”

“THE HUMBLE, THOUGH MORE PROFITABLE ART”: PANORAMIC SPECTACLES IN THE AMERICAN ENTERTAINMENT WORLD, 1794- 1850 by Nalleli Guillen A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Spring 2018 © 2018 Nalleli Guillen All Rights Reserved “THE HUMBLE, THOUGH MORE PROFITABLE ART”: PANORAMIC SPECTACLES IN THE AMERICAN ENTERTAINMENT WORLD, 1794- 1850 by Nalleli Guillen Approved: __________________________________________________________ Arwen P. Mohun, Ph.D. Chair of the Department of History Approved: __________________________________________________________ George H. Watson, Ph.D. Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences Approved: __________________________________________________________ Ann L. Ardis, Ph.D. Senior Vice Provost for Graduate and Professional Education I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Signed: __________________________________________________________ Katherine C. Grier, Ph.D. Professor in charge of dissertation I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Signed: __________________________________________________________ Rebecca L. Davis, Ph.D. Member of dissertation committee I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Signed: __________________________________________________________ David Suisman, Ph.D. Member of dissertation committee I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. -

Rembrandt Peale: a Chronology

Rembrandt Peale: A Chronology Abbreviations ReP Rembrandt Peale CWP Charles Willson Peale AAFA American Academy oj Fine Art APS American Philosophical Society CHS Central High School HSP Historical Society oj Pennsylvania NAD National Academy oj Design PA FA Pennsylvania Academy oj the Fine Arts SOA Society oj Artists 1776 Charles Willson Peale moves family from Maryland June to Philadelphia. Household includes CWP, wife Rachel Brewer Peale, two-year-old Raphaelle, six- month-old Angelica, niece and nephew Peggy and Charles Peale Polk, Grandmother Peale, cousin and nurse Peggy Durgan, and two slaves. 1777 CWP, now a militia officer, takes family to Van Ars- October dalen farm north of Philadelphia as British occupy city. 1778 Rembrandt (ReP) is born to Rachel and CWP at February farm. He is seventh child and third to survive. 22 June Family returns to city when British evacuate the area. August 29 ReP is baptised by the Rev. Dr. John Ewing at First Presbyterian Church. 1780 Titian Ramsay Peale is born. August 1 13 0 NOTES AND DOCUMENTS January 1782 CWP enlarges his house at Third and Lombard to ac- comodate sky-lit exhibition rooms as he begins painting commemorative portraits for gallery of revolutionary heroes. 1784 Rubens Peale is born. May 1 c. 1782- ReP amuses himself in CWPs carpentry shop, learn- 1786 ing to use tools. Builds easel, writing desk; stores dis- carded brushes and paint bladders in box he makes. Sorts CWPs collections of engravings; copies Roman letters from broadsides. Reads lives of painters. [Les- ter.]1 1786 Sophonisba Angusciola Peale is born. -

IEDALLION of FRANKLIN PEALE Yo the Aenican Phfomophical Society and the Hiutrical Sucity of Pemogivamim

II k IEDALLION OF FRANKLIN PEALE yo the Aenican PhFomophical Society and the Hiutrical Sucity of Pemogivamim. THE MISSION OF FRANKLIN PEALE TO EUROPE, 1833 TO 1835 By JAMES L. WHITEHEAD A MONG the numerous sons of Charles Willson Peale, painter aand scientist, was Franklin, one of the few Peale children not named for a Renaissance artist. His name, however, was no less auspicious than those of his brothers and sisters, and his birth was probably more so. He was born October 15, 1795, in the Hall of the American Philosophical Society and was presented four months later to that distinguished group, with the request that the Society give him a name. It was decided that none could be more suitable than that of the first President of the Society-Franklin. In view of this spectacular introduction to life, it is unfortunate that history has granted him so little fame after his death. Franklin Peale, however, was a man of no small reputation dur- ing his lifetime. He was well trained in mechanical and scientific subjects, and his home in Philadelphia was a gathering place of cultured people. After his father's death in 1827, he was placed in charge of the Philadelphia Museum, which his father had opened in 1794 in the building of the Philosophical Society. He kept that position until 1833. In that year he resigned and took a position with the United States Mint as Assistant Assayer. Peale's appointment at the Mint came as the result of the desire of the Director to send a commissioner abroad to study European mints. -

Through Colonial Doorways

THROUGH I COLONIAL f <DOOKx\AYSit LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA. I GIFT OF GEORGE MOREY RICHARDSON. Received, August, 1898. No. Class No. J ..(?.# .... ^^&5?&XMEH&Z^JiZ&^XM% THROUGH COLONIAL DOORWAYS TENTH EDITION OF THB UNIVERSITY THROUGH COLONIAL DOORWAYS BY ANNE HOLLINGSWOKTH WHARTON PHILADELPHIA J.B.LI PP1NCOTT COMPANY MDCCCXCIII xM v5t) ,\AH COPYRIGHT, 1893, BY J. B. LIPPINCOTT COMPANY. PRINTED BY J. B. LIPPINCOTT COMPANY, PHILADELPHIA. TO THE MEMORY OF MARGARET N. CARTER, WHOSE LIVING AND LOVING PRESENCE WAS AN IN SPIRATION DURING THE PREPARATION OF THESE CHAPTERS, AND WHOSE SKETCHES ARE AMONG THOSE THAT ADORN ITS PAGES, THIS LITTLE VOLUME is THE revival of interest in Colonial and Revolutionary times has become a marked feature of the life of to-day. Its mani festations are to be found in the litera ture which has grown up around these individual periods, and in the painstaking research being made among documents and records of the past with genealogical and historical intent. Not only has a desire been shown to learn more of the great events of the last century, but with it has come an altogether natural curiosity to gain some insight into the social and domestic life of Colonial days. To read of councils, congresses, and battles is not enough : men and women wish to know something more intimate Vlll PREFACE. and personal of the life of the past, of how their ancestors lived and loved as well of how they wrought, suffered, and died. With some thought of gratifying this de sire, by sounding the heavy brass knocker, and inviting the reader to enter with us through the broad doorways of some Colo nial homes into the hospitable life within, have these pages been written. -

Peale-Sellers Family Collection, 1686-1963 1686-1963 Mss.B.P31

Peale-Sellers Family Collection, 1686-1963 1686-1963 Mss.B.P31 American Philosophical Society 105 South Fifth Street Philadelphia, PA, 19106 215-440-3400 [email protected] Peale-Sellers Family Collection, 1686-1963 Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 3 Background note ......................................................................................................................................... 5 Scope & content ........................................................................................................................................13 Related Materials ...................................................................................................................................... 14 Indexing Terms ......................................................................................................................................... 14 Other Descriptive Information ..................................................................................................................17 Other Descriptive Information ..................................................................................................................17 Other Descriptive Information ..................................................................................................................17 Collection Inventory ..................................................................................................................................18 -

The Construction of a Gendered Memory in Philadelphia and Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, 1860-1914

FOR THE LOVE OF ONE’S COUNTRY: THE CONSTRUCTION OF A GENDERED MEMORY IN PHILADELPHIA AND MONTGOMERY COUNTY, PENNSYLVANIA, 1860-1914 _______________________________________________________________________ A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board ________________________________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor Of Philosophy ________________________________________________________________________ By Smadar Shtuhl May, 2011 Examining Committee Members: Susan E. Klepp, Advisory Chair, History Wilbert L. Jenkins, History Jonathan Daniel Wells, History Rebecca T. Alpert, External Member, Temple University © by Smadar Shtuhl 2011 All Rights Reserved ii ABSTRACT The acquisition of the home of George Washington by the Mount Vernon Ladies Association in 1858 was probably the first preservation project led by women in the United States. During the following decades, elite Philadelphia and Montgomery County women continued the construction of historical memory through the organization and popularization of exhibitions, fundraising galas, preservation of historical sites, publication of historical writings, and the erection of patriotic monuments. Drawing from a wide variety of sources, including annual organizations’ reports, minutes of committees and of a DAR chapter, correspondence, reminiscences, newspapers, circulars, and ephemera, the dissertation argues that privileged women constructed a classed and gendered historical memory, which aimed to write women into the national historical narrative and present themselves as custodians of history. They constructed a subversive historical account that placed women on equal footing with male historical figures and argued that women played a significant role in shaping the nation’s history. During the first three decades, privileged women advanced an idealized memory of Martha and George Washington with an intention to reconcile the sectional rift caused by the Civil War. -

Visualizing Native People in Philadelphia's Museums: Public Views and Student Reviews

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Department of Anthropology Papers Department of Anthropology 1-17-2018 Visualizing Native People in Philadelphia's Museums: Public Views and Student Reviews Margaret Bruchac University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/anthro_papers Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, and the Museum Studies Commons Recommended Citation Bruchac, M. (2018). Visualizing Native People in Philadelphia's Museums: Public Views and Student Reviews. Penn Museum Blog, Retrieved from https://repository.upenn.edu/anthro_papers/174 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/anthro_papers/174 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Visualizing Native People in Philadelphia's Museums: Public Views and Student Reviews Abstract Material representations of Indigenous history in public museums do more than merely present the past. Exhibitions are always incomplete and idiosyncratic, revealing only a small window into the social worlds of diverse human communities. Museums create, in essence, staged assemblages: compositions of objects, documents, portraits, and other material things that have been filtered through an array of influences. These influences—museological missions, collection ocessses,pr curatorial choices, loan possibilities, design concepts, research specialties, funding options, consultant opinions, space limitations, time limits, logistical challenges, etc.—will be unique for -

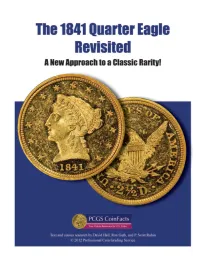

The 1841 Quarter Eagle in Context: Why There Were No Circulation Strikes by Ron Guth

Dedicated to David Akers Introduction The 1841 Quarter Eagle is one of the most famous United States coin rarities, and it also represents one of the great mysteries of U.S. numismatics. An extremely small number of 1841 Quarter eagles were struck at the Philadelphia Mint. There are no Mint records of the striking(s?) of this issue, though in 1842, Jacob Reese Eckfeldt and William E. Dubois recorded the existence of an example in the Mint Cabinet in their book, A Manual of Gold and Silver Coins of All Nations, Struck Within the Past Century. In 1860, James Ross Snowden referred to this issue as a “pattern” and noted that “only a few specimens were struck, one of which is now in the Mint Cabinet.” The first recorded sale of an 1841 Quarter Eagle was in the 1873 sale of the Seavey collection. Until the 1940s, there were very few recorded sales of this rarity. In the 1950s, Norman Stack gave the 1841 Quarter Eagle the nickname that is still carries today…the “Little Princess.” There have been several dozen sales of the 1841 Quarter Eagle since the 1940s and in each instance, the “Little Princess” has been described as a “proof-only” issue. But not everyone in the numismatic community has been convinced that this was the case. Several experts, most notably David Akers, have postulated that both proofs and circulation strikes of the 1841 Quarter Eagle were minted. For the past two years, PCGS CoinFacts experts, with much help from other numismatic experts, have conducted an intensive study of 1841 Quarter Eagles to answer the monumental questions surrounding this extremely rare issue: “Was the 1841 Quarter Eagle a proof-only issue? Or “Were any 1841 Quarter Eagles made for circulation?” The startling conclusion to our research is that not all 1841 Quarter Eagles were struck as proofs.