Visualizing Native People in Philadelphia's Museums: Public Views and Student Reviews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charles Roberts Autograph Letters Collection MC.100

Charles Roberts Autograph Letters collection MC.100 Last updated on January 06, 2021. Haverford College Quaker & Special Collections Charles Roberts Autograph Letters collection Table of Contents Summary Information....................................................................................................................................7 Administrative Information........................................................................................................................... 7 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................7 Collection Inventory...................................................................................................................................... 9 110.American poets................................................................................................................................. 9 115.British poets.................................................................................................................................... 16 120.Dramatists........................................................................................................................................23 130.American prose writers...................................................................................................................25 135.British Prose Writers...................................................................................................................... 33 140.American -

New York Painting Begins: Eighteenth-Century Portraits at the New-York Historical Society the New-York Historical Society Holds

New York Painting Begins: Eighteenth-Century Portraits at the New-York Historical Society The New-York Historical Society holds one of the nation’s premiere collections of eighteenth-century American portraits. During this formative century a small group of native-born painters and European émigrés created images that represent a broad swath of elite colonial New York society -- landowners and tradesmen, and later Revolutionaries and Loyalists -- while reflecting the area’s Dutch roots and its strong ties with England. In the past these paintings were valued for their insights into the lives of the sitters, and they include distinguished New Yorkers who played leading roles in its history. However, the focus here is placed on the paintings themselves and their own histories as domestic objects, often passed through generations of family members. They are encoded with social signals, conveyed through dress, pose, and background devices. Eighteenth-century viewers would have easily understood their meanings, but they are often unfamiliar to twenty-first century eyes. These works raise many questions, and given the sparse documentation from the period, not all of them can be definitively answered: why were these paintings made, and who were the artists who made them? How did they learn their craft? How were the paintings displayed? How has their appearance changed over time, and why? And how did they make their way to the Historical Society? The state of knowledge about these paintings has evolved over time, and continues to do so as new discoveries are made. This exhibition does not provide final answers, but presents what is currently known, and invites the viewer to share the sense of mystery and discovery that accompanies the study of these fascinating works. -

ESSSAR Masthead

EMPIRE PATRIOT Empire State Society of the Sons of the American Revolution Descendants of America’s First Soldiers Volume 10 Issue 1 February 2008 Printed Four Times Yearly THE CONCLUSION OF . THE PHILADELPHIA CAMPAIGN In Summary: We started this journey several issues ago beginning with . LANDING AT THE HEAD OF ELK - Over 260 British ships arrived at Head of Elk, Maryland. Washington was ready. The trip took overly long, horses died by the hundreds. British General Howe was anxious to move on, but first he had to unload his massive armada. ON THE MARCH TO BRANDYWINE - Howe heads for Philadelphia. Washington blocks the path. On the way to their first engagement of 1777, Washington exposes himself to capture, Howe misses an opportunity, the rains fall, and everyone seems prepared for what happens next. THE BATTLE OF BRANDYWINE- The first battle in the campaign. Howe conceives and executes a daring 17 mile march catching Washington by surprise. The Continental Army is impressive, but the day belongs to the British. THE BATTLE OF THE CLOUDS Both armies were poised for another major engagement Five days after the Battle of Brandywine, a confrontation is rained out PAOLI MASSACRE Bloody bayonets in a midnight raid Mad” Anthony Wayne, assigned to attack the rear guard of the British army, is himself surprised in a “dirty” early morning raid. MARCH TO GERMANTOWN Washington prepares to win back the capital Congress flees Philadelphia as the British occupy the city amid chaos and fear. THE BATTLE OF GERMANTOWN The battle is fought in and around a mansion. For the first time the British retreat during battle, but fog and confusion turned the American advance around. -

Signers of the United States Declaration of Independence Table of Contents

SIGNERS OF THE UNITED STATES DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE 56 Men Who Risked It All Life, Family, Fortune, Health, Future Compiled by Bob Hampton First Edition - 2014 1 SIGNERS OF THE UNITED STATES DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTON Page Table of Contents………………………………………………………………...………………2 Overview………………………………………………………………………………...………..5 Painting by John Trumbull……………………………………………………………………...7 Summary of Aftermath……………………………………………….………………...……….8 Independence Day Quiz…………………………………………………….……...………...…11 NEW HAMPSHIRE Josiah Bartlett………………………………………………………………………………..…12 William Whipple..........................................................................................................................15 Matthew Thornton……………………………………………………………………...…........18 MASSACHUSETTS Samuel Adams………………………………………………………………………………..…21 John Adams………………………………………………………………………………..……25 John Hancock………………………………………………………………………………..….29 Robert Treat Paine………………………………………………………………………….….32 Elbridge Gerry……………………………………………………………………....…….……35 RHODE ISLAND Stephen Hopkins………………………………………………………………………….…….38 William Ellery……………………………………………………………………………….….41 CONNECTICUT Roger Sherman…………………………………………………………………………..……...45 Samuel Huntington…………………………………………………………………….……….48 William Williams……………………………………………………………………………….51 Oliver Wolcott…………………………………………………………………………….…….54 NEW YORK William Floyd………………………………………………………………………….………..57 Philip Livingston…………………………………………………………………………….….60 Francis Lewis…………………………………………………………………………....…..…..64 Lewis Morris………………………………………………………………………………….…67 -

Philadelphia and the Southern Elite: Class, Kinship, and Culture in Antebellum America

PHILADELPHIA AND THE SOUTHERN ELITE: CLASS, KINSHIP, AND CULTURE IN ANTEBELLUM AMERICA BY DANIEL KILBRIDE A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 1997 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS In seeing this dissertation to completion I have accumulated a host of debts and obligation it is now my privilege to acknowledge. In Philadelphia I must thank the staff of the American Philosophical Society library for patiently walking out box after box of Society archives and miscellaneous manuscripts. In particular I must thank Beth Carroll- Horrocks and Rita Dockery in the manuscript room. Roy Goodman in the Library’s reference room provided invaluable assistance in tracking down secondary material and biographical information. Roy is also a matchless authority on college football nicknames. From the Society’s historian, Whitfield Bell, Jr., I received encouragement, suggestions, and great leads. At the Library Company of Philadelphia, Jim Green and Phil Lapansky deserve special thanks for the suggestions and support. Most of the research for this study took place in southern archives where the region’s traditions of hospitality still live on. The staff of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History provided cheerful assistance in my first stages of manuscript research. The staffs of the Filson Club Historical Library in Louisville and the Special Collections room at the Medical College of Virginia in Richmond were also accommodating. Special thanks go out to the men and women at the three repositories at which the bulk of my research was conducted: the Special Collections Library at Duke University, the Southern Historical Collection of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and the Virginia Historical Society. -

Charles Coleman Sellers Collection Circa 1940-1978 Mss.Ms.Coll.3

Charles Coleman Sellers Collection Circa 1940-1978 Mss.Ms.Coll.3 American Philosophical Society 3/2002 105 South Fifth Street Philadelphia, PA, 19106 215-440-3400 [email protected] Charles Coleman Sellers Collection ca.1940-1978 Mss.Ms.Coll.3 Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 3 Background note ......................................................................................................................................... 5 Scope & content ..........................................................................................................................................6 Administrative Information .........................................................................................................................7 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................ 7 Indexing Terms ........................................................................................................................................... 7 Bibliography ................................................................................................................................................9 Collection Inventory ..................................................................................................................................10 Series I. Charles Willson Peale Portraits & Miniatures........................................................................10 -

William Penn's Chair and George

WILLIAM PENN’S CHAIR AND GEORGE WASHINGTON’S HAIR: THE POLITICAL AND COMMERCIAL MEANINGS OF OBJECTS AT THE PHILADELPHIA GREAT CENTRAL FAIR, 1864 by Justina Catherine Barrett A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Early American Culture Spring 2005 Copyright 2005 Justina Catherine Barrett All rights reserved Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 1426010 Copyright 2005 by Barrett, Justina Catherine All rights reserved. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ® UMI UMI Microform 1426010 Copyright 2005 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. WILLIAM PENN’S CHAIR AND GEORGE WASHINGTON’S HAIR: THE POLITICAL AND COMMERCIAL MEANINGS OF OBJECTS AT THE PHILADELPHIA GREAT CENTRAL FAIR, 1864 By Justina Catherine Barrett Approved: _______ Pauline K. Eversmann, M. Phil. Professor in charge of thesis on behalf of the Advisory Committee Approved: J. -

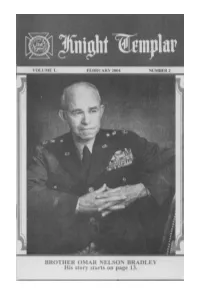

Knight Templar Magazine

Grand Master's Message for February 2004 February brings many pleasant and yet poignant memories. It is, of course, the month in which we remember those dear to us with Valentine's Day (another day of love). We are so fortunate to have those ladies in our lives who have done so much for us; our wives, mothers, sisters, daughters, etc. Speaking for the Sir Knights, we do appreciate everything that you have done for us. Many of our ladies are members of the Social Order of the Beauceant, which has raised tens of thousands of dollars, annually, for the Knights Templar Eye Foundation. Some states do not have the S.O.O.B. but do have ladies' auxiliaries, which also help their Commanderies and the Eye Foundation. Sir Knights, be sure that you recognize and thank your ladies. Some roses, candy, or whatever makes her happy would be good. She will probably wonder, what the devil you have been doing to cause you to take this action, but the net result should be good. This February is in a "Leap Year," which reminds me of a dear aunt who was born on February 29. When she passed away, she had celebrated 21 birthdays. She was my mother's next older sister and was a true workaholic. She loved to fish and would catch fish no matter what it took to catch them. Happy Birthday, Aunt Lenora! Another February memory was the tradition at our house of pruning our rose bushes on or around Valentine's Day. This was at a time when the bush was dormant and pruning would have the best effect on the bush as it came to life and began growing again in the spring. -

National Historical Park Pennsylvania

INDEPENDENCE National Historical Park Pennsylvania Hall was begun in the spring of 1732, when from this third casting is the one you see In May 1775, the Second Continental Con The Constitutional Convention, 1787 where Federal Hall National Memorial now ground was broken. today.) gress met in the Pennsylvania State House stands. Then, in 1790, it came to Philadel Edmund Woolley, master carpenter, and As the official bell of the Pennsylvania (Independence Hall) and decided to move The Articles of Confederation and Perpet phia for 10 years. Congress sat in the new INDEPENDENCE ual Union were drafted while the war was in Andrew Hamilton, lawyer, planned the State House, the Liberty Bell was intended to from protest to resistance. Warfare between County Court House (now known as Con building and supervised its construction. It be rung on public occasions. During the the colonists and British troops already had progress. They were agreed to by the last of gress Hall) and the United States Supreme NATIONAL HISTORICAL PARK was designed in the dignity of the Georgian Revolution, when the British Army occupied begun in Massachusetts. In June the Con the Thirteen States and went into effect in Court in the new City Hall. In Congress period. Independence Hall, with its wings, Philadelphia in 1777, the bell was removed gress chose George Washington to be Gen the final year of the war. Under the Arti Hall, George Washington was inaugurated has long been considered one of the most to Allentown, where it was hidden for almost eral and Commander in Chief of the Army, cles, the Congress met in various towns, only for his second term as President. -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory

Form No. ^0-306 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR FEDERAL PROPERTIES SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Independence National Historical Park AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREET & NUMBER 313 Walnut Street CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT t Philadelphia __ VICINITY OF STATE CODE COUNTY CODE PA 19106 CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE ^DISTRICT —PUBLIC —OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE 2LMUSEUM -BUILDING(S) —PRIVATE X-UNOCCUPIED —^COMMERCIAL 2LPARK .STRUCTURE 2EBOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —XEDUCATIONAL ^.PRIVATE RESIDENCE -SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS -OBJECT —IN PROCESS X-YES: RESTRICTED ^GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: REGIONAL HEADQUABIER REGION STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE PHILA.,PA 19106 VICINITY OF COURTHOUSE, ____________PhiladelphiaREGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC. _, . - , - , Ctffv.^ Hall- - STREET & NUMBER n^ MayTftat" CITY. TOWN STATE Philadelphia, PA 19107 TITLE DATE —FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY _LOCAL CITY. TOWN CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE ^EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED 2S.ORIGINALSITE _GOOD h^b Jk* SANWJIt's ALTERED _MOVED DATE. —FAIR _UNEXPOSED Description: In June 1948, with passage of Public Law 795, Independence National Historical Park was established to preserve certain historic resources "of outstanding national significance associated with the American Revolution and the founding and growth of the United States." The Park's 39.53 acres of urban property lie in Philadelphia, the fourth largest city in the country. All but .73 acres of the park lie in downtown Phila-* delphia, within or near the Society Hill and Old City Historic Districts (National Register entries as of June 23, 1971, and May 5, 1972, respectively). -

Selected Peale Family Papers

Selected Peale family papers Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 2 Container Listing ...................................................................................................... Selected Peale family papers AAA.pealpeal Collection Overview Repository: Archives of American Art Title: Selected Peale family papers Identifier: AAA.pealpeal Date: 1803-1854 Creator: Peale family Extent: 3 Microfilm reels (3 partial microfilm reels) Language: English . Administrative Information Acquisition Information Microfilmed by the Historical Society of Pennsylvania for the Archives of American Art, 1955. Location of Originals REEL P21: Originals in the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Peale family papers. Location of Originals REEL P23, P29: Originals in the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, -

The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts

THE PENNSYLVANIA ACADEMY OF THE FINE ARTS BROAD AND CHERRY 5T5. • PHILADELPHIA 153rd ANNUAL REPORT 1958 Cover: The Fish House Door by John F. Peto Collection Fund Purchase 1958 the One-Hundred and Fifty-third Annual Report of THE PENNSYLVANIA ACADEMY OF THE FINE ARTS FOR THE YEAR 1958 Presented to the Meeting of the Stockholders of the Academy on February 2, 1959 OFFICERS John F. Lewis, Jr. President, 1949-0ctober, 1958 Henry S. Drinker Vice-Pres., 1933-0ctober, 1958; President, October, 1958- C. Newbold Taylor . Treasurer Joseph T. Fraser, Jr. Director and Secretary BOARD OF DIRECTORS Mrs. Leonard T. Beale Arthur C. Kaufmann Howard C. Petersen Mrs. Richardson Dilworth* John F. Lewis, Jr. George B. Roberts Henry S. Drinker James P. Magill Raymond A. Speiser David Gwinn Fredric R. Mann* John Stewart George Harding* Sydney E. Martin C. Newbold Taylor Frank T. Howard Mrs. Herbert C. Morris Mrs. Elias Wolf* R. Sturgis Ingersoll George P. Orr** Sydney L. Wright * Ex-officio Alfred Zantzinger **Resigned Sept_ 1958 STANDING COMMITTEES COMM ITT EE ON COLL EC TI ONS AND EX HI BITIONS George B. Roberts, Chairman Mrs. Leonard T. Beale R. Sturgis Ingersoll Alfred Zantzinger CO MM ITTEE O N FIN AN CE C. Newbold Taylor Chairman James P. Magill John Stewart COMM ITTEE ON IN ST RU CTION James P. Magill, Chairman Mrs. Leonard T. Beale Mrs. Richardson Dilworth David Gwinn Mrs. Elias Wolf SOLICITOR Maurice B. Saul WOMEN'S COMMITTEE Mrs. Hart McMichael . Chairman to May, 1958 Mrs. Elias Wolf . Chairman, May, 1958- Mrs. George B. Roberts Corresponding Secretary-Treasurer Mrs.