The Adjudication of Slave Ship Captures, Coercive Intervention, and Value Exchange in Comparative Atlantic Perspective, Ca

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Africa Journal of the International African Institute Revue De Rinstitut Africain International Volume 57, 1987

Africa Journal of the International African Institute Revue de rinstitut Africain International Volume 57, 1987 Edited by Murray Last Reviews Editor Paul Richards I-A-I Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.40.40, on 02 Oct 2021 at 10:17:45, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0001972000083091 AFRICA Vol. 57 No. 4 1987 Editors • Redacteurs Murray Last • Paul Richards Consultant editor • Christopher Fyfe • Ridacteur consultatif Reviews Editor • Paul Richards • Ridacteur, comptes rendus Consultant Editors • Redacteurs consultatifs A. E. Afigbo • Abdel Ghaffer M. Ahmed • W. van Binsbergen • John Comaroff • Gudrun Dahl • Katsuyoshi Fukui • C. Magbaily Fyle J. A. K. Kandawire • Carol P. MacCormack • Wyatt MacGaffey • Adolfo Mascarenhas • J.-C. Muller • Moriba Toure Sierra Leone, 1787-1987 Foreword • by the Vice-Chancellor, University of Sierra Leone 407 Introduction 408 History and politics 1787-1887-1987: reflections on a Sierra Leone bicentenary • Christopher Fyfe 411 The dissolution of Freetown City Council in 1926: a negative example of political apprenticeship in colonial Sierra Leone • AkintolaJ. G. Wyse 422 Women in Freetown politics, 1914-61: a preliminary study • LaRayDenzer 439 Ecology and technology The socio-ecology of firewood and charcoal on the Freetown peninsula • R. Akindele Cline^Cole 457 Culture, technology and policy in the informal sector: attention to endogenous development • C. Magbaily Fyle 498 Photography in Sierra Leone, 1850-1918 • Vera Viditz-Ward 510 Culture and language The national languages of Sierra Leone: a decade of policy experimentation • JokoSengova 519 Journal of the International African Institute Revue de l'lnstitut Africain International Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. -

From Murmuring to Mutiny Bruce Buchan School of Humanities, Languages and Social Sciences Griffith University

Civility at Sea: From Murmuring to Mutiny Bruce Buchan School of Humanities, Languages and Social Sciences Griffith University n 1749 the articles of war that regulated life aboard His Britannic Majesty’s I vessels stipulated: If any Person in or belonging to the Fleet shall make or endeavor to make any mutinous Assembly upon any Pretense whatsoever, every Person offending herein, and being convicted thereof by the Sentence of the Court Martial, shall suffer Death: and if any Person in or belong- ing to the Fleet shall utter any Words of Sedition or Mutiny, he shall suffer Death, or such other Punishment as a Court Martial shall deem him to deserve. [Moreover] if any Person in or belonging to the Fleet shall conceal any traitorous or mutinous Words spoken by any, to the Prejudice of His Majesty or Government, or any Words, Practice or Design tending to the Hindrance of the Service, and shall not forthwith reveal the same to the Commanding Officer; or being present at any Mutiny or Sedition, shall not use his utmost Endeavors to suppress the same, he shall be punished as a Court Martial shall think he deserves.1 These stern edicts inform a common image of the cowed life of ordinary sailors aboard vessels of the Royal Navy during its golden age, an image affirmed by the testimony of Jack Nastyface (also known as William Robinson, 1787–ca. 1836), for whom the sailor’s lot involved enforced silence under threat of barbarous and tyrannical punishment.2 In the soundscape of maritime life 1 Articles 19 and 20 of An Act for Amending, Explaining and Reducing into One Act of Parliament, the Laws Relating to the Government of His Majesty’s Ships, Vessels and Forces by Sea (also known as the 1749 Naval Act or the Articles of War), 22 Geo. -

PIRATES Ssfix.Qxd

E IFF RE D N 52 T DISCOVERDISCOVER FAMOUS PIRATES B P LAC P A KBEARD A IIRRAATT Edward Teach, E E ♠ E F R better known as Top Quality PlayingPlaying CardsCards IF E ♠ SS N Plastic Coated D Blackbeard, was T one of the most feared and famous 52 pirates that operated Superior Print along the Caribbean and A Quality PIR Atlantic coasts from ATE TR 1717-18. Blackbeard ♦ EAS was most infamous for U RE his frightening appear- ance. He was huge man with wild bloodshot eyes, and a mass of tangled A hair and beard that was twisted into dreadlocks, black ribbons. In battle, he made himself andeven thenmore boundfearsome with by ♦ wearing smoldering cannon fuses stuffed under his hat, creating black smoke wafting about his head. During raids, Blackbeard car- ried his cutlass between his teeth as he scaled the side of a The lure of treasure was the driving force behind all the ship. He was hunted down by a British Navy crew risks taken by Pirates. It was ♠ at Ocracoke Inlet in 1718. possible to acquire more booty Blackbeard fought a furious battle, and was slain ♠ in a single raid than a man or jewelry. It was small, light, only after receiving over 20 cutlass wounds, and could earn in a lifetime of regu- and easy to carry and was A five pistol shots. lar work. In 1693, Thomas widely accepted as currency. A Tew once plundered a ship in Other spoils were more WALKING THE PLANK the Indian Ocean where each practical: tobacco, weapons, food, alco- member received 3000 hol, and the all important doc- K K ♦ English pounds, equal to tor’s medical chest. -

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS During the ten years that were spent in editing the three African Series volumes, the Marcus Garvey and Universal Negro Improvement Association Papers project has incurred an unusually large number of institutional, intel- lect jal, and personal debts. The preparation of the volumes would never have bee i possible without the continuing support and assistance of a wide array of nanuscript librarians, archivists, university libraries, scholars, funding age icies, university administrators, fellow editors, and friends. While the debts thus accrued over the past decade can never be adequately discharged, it is still a great pleasure to acknowledge them. They form an integral part of whatever permanent value these volumes possess. We would like here to acknowledge our deep appreciation to so many for contributing so greatly to this endeavor. In a real sense, these volumes represent the fruition of the efforts of many hands that have worked selflessly to assist in documenting the story of the African Garvey movement. We would like to thank the many archives and manuscript collections that hav ; contributed documents as well as assisted the project by responding with unfiiling courtesy and promptness to our innumerable queries for informa- dor : American Colonization Society Papers; Archives africaines, Place Royale, Brussels; Archives de Ministère des affaires étrangères, Paris; Archives du Senegal, Dakar; Archives nationales du Cameroun, Yaounde; Archives of the Département évangélique français d'action apostolique, Paris; -

Tee 1919 Race Riots in Britain: Ti-Lir Background and Conseolences

TEE 1919 RACE RIOTS IN BRITAIN: TI-LIR BACKGROUND AND CONSEOLENCES JACOLEUNE .ENKINSON FOR TI-E DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF EDINBURGH 1987 ABSTRACT OF THESIS This thesis contains an empirically-based study of the race riots in Britain, which looks systematically at each of the nine major outbreaks around the country. It also looks at the background to the unrest in terms of the growing competition in the merchant shipping industry in the wake of the First World War, a trade in which most Black residents in this country were involved. One result of the social and economic dislocation following the Armistice was a general increase in the number of riots and disturbances in this country. This factor serves to put into perspective the anti-Black riots as an example of increased post-war tension, something which was occurring not only in this country, but worldwide, often involving recently demobilised men, both Black and white. In this context the links between the riots in Britain and racial unrest in the West Indies and the United States are discussed; as is the growth of 'popular racism' in this country and the position of the Black community in Britain pre- and post- riot. The methodological approach used is that of Marxist historians of the theory of riot, although this study in part, offers a revision of the established theory. ACKNOWLEDcEJvNTS I would like to thank Dr. Ian Duffield, my tutor and supervisor at Edinburgh University, whose guidance and enthusiasm helped me along the way to the completion of this thesis. -

Wildwill's Collector's Guide to Wizkids' Pirates of the Spanish Main

WildWill’s Collector’s Guide to WizKids’ By Captain William “WildWill” Noetling Includes Price Guides, Collector’s Checklists, Bonus Game Scenario and MORE! WildWill’s Collector’s Guide to WizKids’ Pirates of the Spanish Main. Copyright ©2006 by William Noetling. This guide was created for educational and entertainment purposes only. All prices lists are printed as a guide only, and not an offer to buy or sell game pieces. This guide is not sponsored, endorsed, or otherwise affiliated with any of the companies or products featured within this guide. This is not an Official Publication. This guide and its editorial content remain the property of the writer and publisher. Written permission must be obtained from the author to publish, circulate, or otherwise disseminate this guide in any altered form, except for review purposes. All ship, crew and other game piece names and representations remain the property of WizKids. Portions of this guide have previously appeared on the website Pojo.com in a slightly altered form. All Prices Listed are current as of June 2006 and are representative of new “mint- condition” game pieces. Email me at [email protected] Visit my home page at www.geocities.com/wmnoe Join me at www.pojo.com WildWill would like to thank: WizKids Games, Pojo.com, Monica Lond-LeBlanc, Bill ‘Pojo’ Gill, James and Robin Hurwitz, Pat Pritchett, Stephanie Veglia.and Wendy Harrison Special Thanks to all my instructors and TA’s at UCLA from 2004 to 2006, especially: Joseph DiMuro, Michael Allen, Sean Silver, Noah Comet, Lars Larsen, Helen Deutsch and Irene Beesemyer Extra Special Thanks to my loving wife Melissa Pritchett, whom I cannot live without. -

74- %2-42 4264

G. ELGIN. Pistol Sword. No. 254. Patented July 5, 1837. Zerezz/ W22ze war. 774 7/24 74- %2-42 4264 PEERS, photo-LTHOGRAPHER, washingtoN, d. c. UNITED STATES PATENT OFFICE. GEO. ELGIN, OF NEW YORK, N. Y. MPROVEMENT IN THE PSTOL KNIFE OR C UTASS. Specification forming part of Letters Patent No. 254, dated July 5, 1887. s To all tuhon, it inval? concern: m I construct my pistols, knives, and cutlasses Be it known that I, GEORGE ELGIN, of the in any of the known forms, and combine them city, county, and State of New York, late of in the following manner: The handle being the city of Macon, county of Bibb and State the same, the barrel and blade are combined of Georgia, have invented a new and useful by tongue and groove with a screw or screws, instrument called the Pistol-Knife or Pistol or the barrel and blade can be made solid, or Cutlass; and I do hereby declare that the foll the two can be soldered in such manner as to lowing is a true and exact description. be firm and Substantial. The barrel is com The nature of my invention consists in com bined on the top or back of the knife or cut bining the pistol and Bowie knife, or the pis lass, and may extend to any distance to suit tol and cutlass, in such manner that it can be the maker or manufacturer. used with as much ease and facility as either What I claim as my invention, and desire the pistol, knife, or cutlass could be if sepa to secure by Letters Patent, is rate, and in an engagement, when the pistol The combination of the pistol and blade in is discharged, the knife (or cutlass) can be the manner above described, using any metals brought into immediate use without changing for the manufacture of those articles which or drawing, as the two instruments are in the will produce the intended effect. -

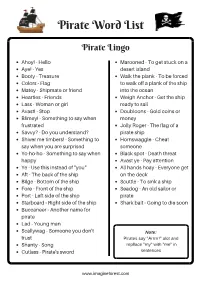

Pirate Word List

Pirate Word List Pirate Lingo Ahoy! - Hello Marooned - To get stuck on a Aye! - Yes desert island Booty - Treasure Walk the plank - To be forced Colors - Flag to walk off a plank of the ship Matey - Shipmate or friend into the ocean Hearties - Friends Weigh Anchor - Get the ship Lass - Woman or girl ready to sail Avast! - Stop Doubloons - Gold coins or Blimey! - Something to say when money frustrated Jolly Roger - The flag of a Savvy? - Do you understand? pirate ship Shiver me timbers! - Something to Hornswaggle - Cheat say when you are surprised someone Yo-ho-ho - Something to say when Black spot - Death threat happy Avast ye - Pay attention Ye - Use this instead of "you" All hands hoay - Everyone get Aft - The back of the ship on the deck Bilge - Bottom of the ship Scuttle - To sink a ship Fore - Front of the ship Seadog - An old sailor or Port - Left side of the ship pirate Starboard - Right side of the ship Shark bait - Going to die soon Buccaneer - Another name for pirate Lad - Young man Scallywag - Someone you don't Note: trust Pirates say "Arrrrr!" alot and Shanty - Song repllace "my" with "me" in Cutlass - Pirate's sword sentences www.imagineforest.com Word Bank abandon contraband hijack plank skull and bones adventure crew hook prowl steal anchor criminal horizon quarters swagger ashore crook hostile quest swashbuckling assault cruel hurricane raid sword attack curse illegal rat thief bad cutthroat infamous rations vandalize bandanna dagger island revenge vanquish bandit danger jewels riches vicious barbaric deck kidnap roam -

Shiver Me Timbers! by Cap’N Tim Huckelbery

Shiver me Timbers! By Cap’n Tim Huckelbery The blasted city of Mordheim has called to many opportunity to join the pirate crew (usually at a Pirate Captain with the song of easy riches, as the point of a cutlass!). As an alternative to the nearby rivers are filled with ships laden with exchanging/ransoming the captured Hero back either gold into the city or departing with to their original Warband (or selling him to wyrdstone. Using the perpetual fog and dust slavers), the Pirate Captain can instead add the which fills the air around the ruins, a ship can captured enemy to the ship’s crew as follows. navigate the city via the deep rivers running Both players roll 2D6, with the Pirate player though it. With lightning speed, the pirate ships adding the Captain’s Leadership and the enemy can appear from nowhere and attack a ship, player adding the Leadership of the captured quickly looting it of any valuables. Some Hero. If either side won that game, it may add Captains have even found safe harbours for +1 to it’s score. their vessels, and lead frequent raiding parties If the Pirate player’s result is higher, the Hero into the city itself. These brave pirate bands renounces his old ways for the life of the high have become new additions to other groups of seas! She or he joins the Crew, either starting a adventurers, fanatics, and nightmare creatures new Crew group or joining an existing one if it that dare enter the remains of the City of the has four models or less. -

COAST of HIGH BARBARY 6/8 Traditional Forecastle Song

THE COAST OF HIGH BARBARY 6/8 Traditional Forecastle Song The Berber (or Barbary) Coast was located off the coast of North Africa, and is not to be confused with the San Francisco Barbary Coast of 1860 located along Broadway. Piracy flourished off the northern coast of Africa as early as the 16th century. This song is good for group singing as it has a refrain after the first line and a second refrain at the end of the second line. I've added the Em Am at the end of lines 1 and 4. Am Em Am Look ahead look a-stern, look a-weather and a-lee, C G Am E7 Blow high, blow low, and so sailéd we C G Am Em I see a wreck to windward and a lofty ship to lee, Am Em Am Sailing down along the coast of High Barbary Am "Oh, hail her!" our Captain called loudly o'er the side C G Am E7 Blow high, blow low, and so sailéd we C G Am Em "Are you a Man-o'-War or are you a privateer?" he cried Am Sailing down along the coast of High Barbary Am "Oh are you a pirate or a Man-o'-War," cried we C G Am E7 Blow high, blow low, and so sailéd we C G Am Em "Oh no, I'm not a pirate but a Man-o'-War," cried he Am Sailing down along the coast of High Barbary Am "Then back up your topsails and heave your vessel to" C G Am E7 Blow high, blow low, and so sailéd we C G Am Em "For we have got some letters to be carried home by you" Am Sailing down along the coast of High Barbary Am "We'll back up our topsails and heave our vessel to" C G Am E7 Blow high, blow low, and so sailéd we C G Am Em "But only in some harbour and along the side of you" Am Sailing down along the coast of -

Louis Froelich: Immigrant, Sword Maker

Louis Froelich: Immigrant, Sword Maker . John T. Frawner, Jr. If you drive through Kenansville, North Carolina, today you might notice a lone highway marker located at the western edge of town on the road leading "from the Court House to Magnolia." The marker reads "Confederate Arms Factory stood here. Made bowie knives, saber-bayo- nets, and other small arms. Destroyed by Federal cavalry, July 4, 1863" (next page). No mention is made of Louis Froelich, a German immigrant, who used his expertise and resourcefulness to produce for the State of North Carolina and the Confederate States of America more than 26,000 edged weapons. Froelich's valuable contribution to the Confederacy was recorded in The Wilmington Journal on April 28, 1864: HOME INDUSTRY - We learn from the Confederate that at the manufactory of Messrs. L. Froelich & Co., enabled to turn out at the quickest notice, all sizes of uni- Kenansville, N. C., from April 1, 1861, to March lst, 1864, form buttons."' Very little is known of the success or failure this establishment has f~~rnished18 sets of surgical instru- of the button operation. ments, 800 gross military buttons, 3,700 lance spears, 6,500 sabre bayonets, 11,700 cavalry sabres, 2,700 officer's In the fall of 1861, Froelich met B. Estvan, a man who sabres, 600 navy cutlasses, 800 artillery cutlasses, 1,700 sets would prove to be of questionable background and char- of infantry accoutrements, 300 sabre belts, and 300 knap- acter. Estvan, situated in Wilmington in early 1861, contact- sacks. ed Governor Clark and offered his services to instruct a company of cavalry in the use of the lance. -

Knives and the Second Amendment

Knives and the Second Amendment By David B. Kopel,1 Clayton E. Cramer2 & Joseph Edward Olson3 This article is a working draft that will be published in 2013 in the University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform Abstract: This Article is the first scholarly analysis of knives and the Second Amendment. Knives are clearly among the “arms” which are protected by the Second Amendment. Under the Supreme Court’s standard in District of Columbia v. Heller, knives are Second Amendment “arms” because they are “typically possessed by law-abiding citizens for lawful purposes,” including self-defense. Bans of knives which open in a convenient way (bans on switchblades, gravity knives, and butterfly knives) are unconstitutional. Likewise unconstitutional are bans on folding knives which, after being opened, have a safety lock to prevent inadvertent closure. Prohibitions on the carrying of knives in general, or of particular knives, are unconstitutional. There is no knife which is more dangerous than a 1 Adjunct Professor of Advanced Constitutional Law, Denver University, Sturm College of Law. Research Director, Independence Institute, Denver, Colorado. Associate Policy Analyst, Cato Institute, Washington, D.C. Kopel is the author of 15 books and over 80 scholarly journal articles, including the first law school textbook on the Second Amendment: NICHOLAS J. JOHNSON, DAVID B. KOPEL, GEORGE A. MOCSARY, & MICHAEL P. O’SHEA, FIREARMS LAW AND THE SECOND AMENDMENT: REGULATION, RIGHTS, AND POLICY (Aspen Publishers, 2012). www.davekopel.org. 2 Adjunct History Faculty, College of Western Idaho. Cramer is the author of CONCEALED WEAPON LAWS OF THE EARLY REPUBLIC: DUELING, SOUTHERN VIOLENCE, AND MORAL REFORM (1999) (cited by Justice Breyer in McDonald v.