All-Bird Conservation Plan (Complete)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

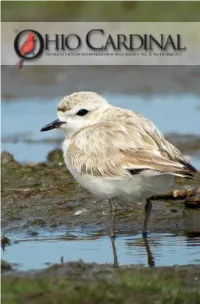

Devoted to the Study and Appreciation of Ohio's Birdlife • Vol. 35, No. 4

Devoted to the Study and Appreciation of Ohio’s Birdlife • Vol. 35, No. 4 Summer 2012 The Orchard Oriole is the smallest oriole in North America, and a common breeder in Ohio. Doug Day caught the interest of this beautiful male on 14 Jun close to his nest in Armleder Park, Hamilton. On the cover: Jerry Talkington obtained a stunning close-up of this Snowy Plover on the Conneaut sandspit. The Ohio rarity moved close to the gathering crowd of birders for good documentation on 02 Jun during its single-day visit. Vol. 35 No. 4 Devoted to the Study and Appreciation of Ohio’s Birdlife EDITOR OHIO BIRD RECORDS Craig Caldwell COMMITTEE 1270 W. Melrose Dr. Greg Miller Westlake, OH 44145 Secretary 440-356-0494 243 Mill Street NW [email protected] Sugarcreek, OH 44681 [email protected] PHOTO EDITOR Laura Keene PAST PUBLISHERS [email protected] John Herman (1978-1980) Edwin C. Pierce (1980-2008) CONSULTANTS Mike Egan PAST EDITORS Victor Fazio III John Herman (1978-1980) Laura Peskin Edwin C. Pierce (1980-1991) Bill Whan Thomas Kemp (1987-1991) Robert Harlan (1991-1996) Victor W. Fazio III (1996-1997) Bill Whan (1997-2008) Andy Jones (2008-2010) Jill M. Russell (2010-2012) ISSN 1534-1666 The Ohio Cardinal, Summer 2012 COMMENTS ON THE SEASON By Craig Caldwell der made separate pilgrimages to Mohican SP and SF in Jun and tallied large numbers of many This was a hot, dry summer in most of Ohio. thrush and warbler species. You will see them cit- Temperatures were above normal in June, part ed repeatedly in the Species Accounts. -

U.S. Lake Erie Lighthouses

U.S. Lake Erie Lighthouses Gretchen S. Curtis Lakeside, Ohio July 2011 U.S. Lighthouse Organizations • Original Light House Service 1789 – 1851 • Quasi-military Light House Board 1851 – 1910 • Light House Service under the Department of Commerce 1910 – 1939 • Final incorporation of the service into the U.S. Coast Guard in 1939. In the beginning… Lighthouse Architects & Contractors • Starting in the 1790s, contractors bid on LH construction projects advertised in local newspapers. • Bids reviewed by regional Superintendent of Lighthouses, a political appointee, who informed U.S. Treasury Dept of his selection. • Superintendent approved final contract and supervised contractor during building process. Creation of Lighthouse Board • Effective in 1852, U.S. Lighthouse Board assumed all duties related to navigational aids. • U.S. divided into 12 LH districts with inspector (naval officer) assigned to each district. • New LH construction supervised by district inspector with primary focus on quality over cost, resulting in greater LH longevity. • Soon, an engineer (army officer) was assigned to each district to oversee construction & maintenance of lights. Lighthouse Bd Responsibilities • Location of new / replacement lighthouses • Appointment of district inspectors, engineers and specific LH keepers • Oversight of light-vessels of Light-House Service • Establishment of detailed rules of operation for light-vessels and light-houses and creation of rules manual. “The Light-Houses of the United States” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, Dec 1873 – May 1874 … “The Light-house Board carries on and provides for an infinite number of details, many of them petty, but none unimportant.” “The Light-Houses of the United States” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, Dec 1873 – May 1874 “There is a printed book of 152 pages specially devoted to instructions and directions to light-keepers. -

2000 Lake Erie Lamp

Lake Erie LaMP 2000 L A K E E R I E L a M P 2 0 0 0 Preface One of the most significant environmental agreements in the history of the Great Lakes took place with the signing of the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement of 1978 (GLWQA), between the United States and Canada. This historic agreement committed the U.S. and Canada (the Parties) to address the water quality issues of the Great Lakes in a coordinated, joint fashion. The purpose of the GLWQA is to “restore and maintain the chemical, physical, and biological integrity of the waters of the Great Lakes Basin Ecosystem.” In the revised GLWQA of 1978, as amended by Protocol signed November 18, 1987, the Parties agreed to develop and implement, in consultation with State and Provincial Governments, Lakewide Management Plans (LaMPs) for lake waters and Remedial Action Plans (RAPs) for Areas of Concern (AOCs). The LaMPs are intended to identify critical pollutants that impair beneficial uses and to develop strategies, recommendations and policy options to restore these beneficial uses. Moreover, the Specific Objectives Supplement to Annex 1 of the GLWQA requires the development of ecosystem objectives for the lakes as the state of knowledge permits. Annex 2 further indicates that the RAPs and LaMPS “shall embody a systematic and comprehensive ecosystem approach to restoring and protecting beneficial uses...they are to serve as an important step toward virtual elimination of persistent toxic substances...” The Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement specifies that the LaMPs are to be completed in four stages. These stages are: 1) when problem definition has been completed; 2) when the schedule of load reductions has been determined; 3) when P r e f a c e remedial measures are selected; and 4) when monitoring indicates that the contribution of i the critical pollutants to impairment of beneficial uses has been eliminated. -

United States Department of the Interior National Park Service Land

United States Department of the Interior National Park Service Land & Water Conservation Fund --- Detailed Listing of Grants Grouped by County --- Today's Date: 11/20/2008 Page: 1 Ohio - 39 Grant ID & Type Grant Element Title Grant Sponsor Amount Status Date Exp. Date Cong. Element Approved District ADAMS 242 - XXX D ELLISON MEMORIAL PARK VILLAGE OF PEEBLES $74,000.00 C 3/7/1973 12/31/1975 2 ADAMS County Total: $74,000.00 County Count: 1 ALLEN 580 - XXX A STRAYER WOODS ACQUISITION JOHNNY APPLESEED METRO PARK DIST. $111,500.00 C 12/6/1977 12/31/1979 4 819 - XXX D OTTAWA RIVER DEVELOPMENT CITY OF LIMA $45,045.00 C 3/21/1980 12/31/1984 4 913 - XXX D VILLAGE PARK VILLAGE OF SPENCERVILLE $11,265.00 C 7/28/1981 12/31/1986 4 ALLEN County Total: $167,810.00 County Count: 3 ASHLAND 93 - XXX D MOHICAN STATE PARK SWIMMING POOL DEPT. OF NATURAL RESOURCES $102,831.30 C 4/23/1971 6/30/1972 16 463 - XXX D MUNICIPAL GOLF COURSE CITY OF ASHLAND $144,615.70 C 4/7/1976 12/31/1978 16 573 - XXX A BROOKSIDE PARK EXPANSION CITY OF ASHLAND $45,325.00 C 11/10/1977 12/31/1979 16 742 - XXX D LEWIS MEMORIAL TENNIS COURTS VILLAGE OF JEROMESVILLE $4,715.00 C 5/2/1979 12/31/1983 16 807 - XXX D BROOKSIDE PARK CITY OF ASHLAND $200,300.00 C 7/14/1980 12/31/1985 16 953 - XXX D BROOKSIDE PARK III CITY OF ASHLAND $269,669.98 C 6/14/1983 12/31/1988 16 1159 - XXX D BROOKSIDE WEST CITY OF ASHLAND $154,500.00 C 7/11/1990 12/31/1995 16 ASHLAND County Total: $921,956.98 County Count: 7 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service Land & Water Conservation Fund --- Detailed Listing of Grants Grouped by County --- Today's Date: 11/20/2008 Page: 2 Ohio - 39 Grant ID & Type Grant Element Title Grant Sponsor Amount Status Date Exp. -

Lighthouses – Clippings

GREAT LAKES MARINE COLLECTION MILWAUKEE PUBLIC LIBRARY/WISCONSIN MARINE HISTORICAL SOCIETY MARINE SUBJECT FILES LIGHTHOUSE CLIPPINGS Current as of November 7, 2018 LIGHTHOUSE NAME – STATE - LAKE – FILE LOCATION Algoma Pierhead Light – Wisconsin – Lake Michigan - Algoma Alpena Light – Michigan – Lake Huron - Alpena Apostle Islands Lights – Wisconsin – Lake Superior - Apostle Islands Ashland Harbor Breakwater Light – Wisconsin – Lake Superior - Ashland Ashtabula Harbor Light – Ohio – Lake Erie - Ashtabula Badgeley Island – Ontario – Georgian Bay, Lake Huron – Badgeley Island Bailey’s Harbor Light – Wisconsin – Lake Michigan – Bailey’s Harbor, Door County Bailey’s Harbor Range Lights – Wisconsin – Lake Michigan – Bailey’s Harbor, Door County Bala Light – Ontario – Lake Muskoka – Muskoka Lakes Bar Point Shoal Light – Michigan – Lake Erie – Detroit River Baraga (Escanaba) (Sand Point) Light – Michigan – Lake Michigan – Sand Point Barber’s Point Light (Old) – New York – Lake Champlain – Barber’s Point Barcelona Light – New York – Lake Erie – Barcelona Lighthouse Battle Island Lightstation – Ontario – Lake Superior – Battle Island Light Beaver Head Light – Michigan – Lake Michigan – Beaver Island Beaver Island Harbor Light – Michigan – Lake Michigan – St. James (Beaver Island Harbor) Belle Isle Lighthouse – Michigan – Lake St. Clair – Belle Isle Bellevue Park Old Range Light – Michigan/Ontario – St. Mary’s River – Bellevue Park Bete Grise Light – Michigan – Lake Superior – Mendota (Bete Grise) Bete Grise Bay Light – Michigan – Lake Superior -

Filling Gaps in the Full Annual Cycle of the Black-Crowned Night-Heron (Nycticorax Nycticorax)

Filling gaps in the full annual cycle of the Black-crowned Night-Heron (Nycticorax nycticorax) Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Kristie A. Stein, B.S. Graduate Program in Environment and Natural Resources The Ohio State University 2018 Thesis Committee: Christopher Tonra, Advisor Jacqueline Augustine Suzanne Gray Laura Kearns Copyrighted by Kristie A. Stein 2018 Abstract Migratory birds carry out different stages of their life cycle in geographically disparate locations, complicating our ability to track individuals over time. However, the importance of connecting these stages is underscored by evidence that processes occurring in one stage can influence performance in subsequent stages. Over half of migratory species in North America are declining, and it follows that understanding the factors limiting population growth is a major focus of current avian conservation. Globally, Black-crowned Night-Herons (Nycticorax nycticorax) are common and widespread, but populations across the Great Lakes region are in long-term decline. Within Ohio, Black-crowned Night-Herons historically nested at 19 colonies but currently occupy only five of those sites. The largest colony, West Sister Island, represents an important breeding area for many species of wading birds and currently hosts the majority of the night-heron breeding population in Ohio. The number of nesting pairs at West Sister Island has been monitored since the 1970s, but little is known about the population outside of the breeding season. My research is the first to examine multiple stages of the full annual cycle of Black-crowned Night-Herons. -

Winter/Spring 2015 Bioohio the Quarterly Newsletter of the Ohio Biological Survey

Winter/Spring 2015 BioOhio The Quarterly Newsletter of the Ohio Biological Survey In This Issue A Note From the Executive Director Abstracts from the I am writing this column on an iPad we really do is describe life. In order to 2015 ONHC ...................... 2 among the clouds at 30,000 feet while preserve life we must understand life, and it traveling to visit family. I am not saying this is this mission that has driven OBS for over in order to brag, but to point out how times a century. We just completed our latest round have changed. Te technologies behind the of grant reviews, and it is encouraging to see MBI Announces 2015 ways in which we communicate and locomote the great projects that are carrying on the Training Courses............... 5 have drastically altered the world in which we tradition of natural history in the state and live, but there can be a stigma associated with the region. Tis year, we awarded $4,500 to refusing to embrace that which is new. If you nine worthy projects covering a variety of taxa CMNH Conservation don’t have an iPhone or an Instagram account and investigating a wide range of ecological, Symposium ....................... 7 or a Twitter handle, you are “old school”—a evolutionary, behavioral, and conservation Luddite; quaint, unimportant, and largely questions. I would encourage you and your irrelevant. Unfortunately, this is often how the students to consider submitting an application Exploring Life in science of natural history is viewed. Expensive for an OBS grant next year. You can fnd Vernal Pools .................. -

Hartig Et Al. 2007. Indicator Project

Cover photos: Landsat 7 satellite image of western Lake Erie Basin and Detroit River corridor provided by USGS Landsat Project; Upper left: angler with walleye (Sander vitreus) by Jim Barta; Middle left: lake sturgeon (Acipenser fulvescens) by Glenn Ogilvie; Lower left: Hexagenia by Lynda Corkum; Center: lake whitefish (Coregonus clupeaformis) by James Boase/U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service; Lower right: juvenile peregrine falcon (Falco peregrinus) by Craig Koppie/U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service; Bottom left: bald eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) by Steve Maslowski/U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. STATE OF THE STRAIT STATUS AND TRENDS OF KEY INDICATORS Edited by: John H. Hartig, Michael A. Zarull, Jan J.H. Ciborowski, John E. Gannon, Emily Wilke, Greg Norwood, and Ashlee Vincent 2007 STATE OF THE STRAIT STATUS AND TRENDS OF KEY INDICATORS 2007 Edited by: John H. Hartig, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Michael A. Zarull, Environment Canada Jan J.H. Ciborowski, University of Windsor John E. Gannon, International Joint Commission Emily Wilke, Southwest Michigan Land Conservancy Greg Norwood, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Ashlee Vincent, University of Windsor Based on the Detroit River-Western Lake Erie Indicator Project, a three-year U.S.-Canada effort to compile and summarize long-term trend data, and the 2006 State of the Strait Conference held in Flat Rock, Michigan Suggested citation: Hartig, J.H., M.A. Zarull, J.J.H. Ciborowski, J.E. Gannon, E. Wilke, G. Norwood, and A. Vincent, eds. 2007. State of the Strait: Status and Trends of Key Indicators. Great Lakes Institute for Environmental Research, Occasional Publication No. -

Atlas Introduction

INTRODUCTION Atlas Methodology The primary goal of the Ohio Breeding Bird Atlas Project was to document the status and distribution of all birds breeding in Ohio between 1982 and 1987. Additional objectives of this project included providing more accurate information on the distri- bution and nesting occurrences of Ohio’s rare and endangered breeding birds; identifying significant habitats supporting rare or unusual species which could become the focus of preservation efforts; providing baseline data against which future changes in the status and distribution of Ohio’s breeding birds can be measured; providing baseline data for the development of environmental impact statements; involving the birders of Ohio in a cooperative effort of scientific value and heightening their awareness of the state’s summer birdlife. This Atlas represents the work of hundreds of birders throughout Ohio who expended over 30,000 hours between 1982 and 1987 collecting data on the distribution of breeding birds in the state. Over 95% of this data was collected between 1983 and 1987 with 1982 serving as a pilot year for the Atlas Project. In order to fully understand and interpret this data, it is necessary to have some understanding of the goals and mechanics of breeding bird atlas projects. Data Collection: Priority Blocks and Special Areas The basis of any atlas project is a grid system whereby the geographical area to be surveyed is divided into a series of smaller sub–units (usually squares or rectangles called blocks). In Ohio, as in a majority of other states conducting breeding bird atlases, the grid system employed is based on the 7.5 minute topographic map system. -

Page 1464 TITLE 16—CONSERVATION § 1132

§ 1132 TITLE 16—CONSERVATION Page 1464 Department and agency having jurisdiction of, and reports submitted to Congress regard- thereover immediately before its inclusion in ing pending additions, eliminations, or modi- the National Wilderness Preservation System fications. Maps, legal descriptions, and regula- unless otherwise provided by Act of Congress. tions pertaining to wilderness areas within No appropriation shall be available for the pay- their respective jurisdictions also shall be ment of expenses or salaries for the administra- available to the public in the offices of re- tion of the National Wilderness Preservation gional foresters, national forest supervisors, System as a separate unit nor shall any appro- priations be available for additional personnel and forest rangers. stated as being required solely for the purpose of managing or administering areas solely because (b) Review by Secretary of Agriculture of classi- they are included within the National Wilder- fications as primitive areas; Presidential rec- ness Preservation System. ommendations to Congress; approval of Con- (c) ‘‘Wilderness’’ defined gress; size of primitive areas; Gore Range-Ea- A wilderness, in contrast with those areas gles Nest Primitive Area, Colorado where man and his own works dominate the The Secretary of Agriculture shall, within ten landscape, is hereby recognized as an area where years after September 3, 1964, review, as to its the earth and its community of life are un- suitability or nonsuitability for preservation as trammeled by man, where man himself is a visi- wilderness, each area in the national forests tor who does not remain. An area of wilderness classified on September 3, 1964 by the Secretary is further defined to mean in this chapter an area of undeveloped Federal land retaining its of Agriculture or the Chief of the Forest Service primeval character and influence, without per- as ‘‘primitive’’ and report his findings to the manent improvements or human habitation, President. -

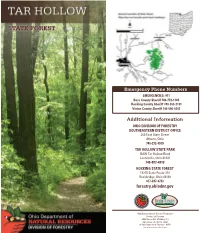

Tar Hollow State Forest

Emergency Phone Numbers EMERGENCIES: 911 Ross County Sheriff 740-773-1185 Hocking County Sheriff 740-385-2131 Vinton County Sheriff 740-596-5242 Additional Information OHIO DIVISION OF FORESTRY SOUTHEASTERN DISTRICT OFFICE 360 East State Street Athens, Ohio 740-272-8519 TAR HOLLOW STATE PARK 16396 Tar Hollow Road Laurelville, Ohio 43135 740-887-4818 HOCKING STATE FOREST 19275 State Route 374 Rockbridge, Ohio 43149 877-247-8733 forestry.ohiodnr.gov Ohio Department of Natural Resources Division of Forestry 2045 Morse Rd., Building H-1 Columbus, OH 43229 - 6693 An Equal Opportunity Employer - M/F/H printed on recycled content paper Welcome to Tar Hollow State Forest Forest History Acquisition of the first state forests began in 1916, originally to Land acquisition for Tar Hollow State Forest began in 1937 as be used as testing grounds for reforestation of tree species. the Ross-Hocking Land Utilization Project. During the 1930s, the Land acquisition later broadened to include land of scenic and federal government formed the Resettlement Administration to recreational values and to restore forest cover to land that had address the impoverished conditions on marginal agricultural been abandoned and abused. Today, Ohio’s 23 state forests areas across the nation. The initial purpose of the program was cover nearly 200,000 acres and provide an abundance of to relocate families to more productive land, thereby enabling benefits for everyone to enjoy. With the advantage of decades them to better sustain a living. Following the relocation the of management, Ohio’s foresters are enhancing nature’s Resettlement Administration initiated the Land Utilization growth cycle, and the state forests continue to produce some Program. -

WEST SISTER ISLAND Horne of the Herons Revisited

WEST SISTER ISLAND Horne of the Herons Revisited Ed Pierce I first visited West Sister I s land in 1982. '!be results of those two trips, June 26 and July 2, are reported in the Ohio Cardinal Vol. 5, No . 2 and Vol. 4, No. 2 (joint issue) pgs. 1-11. On those occasions I made a survey of the Island, counted black crowned night-heron nests and discovered nesting cattle egrets. I had hoped to find a snowy egret colony as there had been a large increase in these birds in the Ottawa National Wildlife Refuge and Magee Marsh Wildlife Area canplex the last t'NO surcmers (nine in 1981 and seventeen in 1982) . However, none were found nor any evidence of any nesting ibis, little blue heron or tri-colored heron. I speculated in that previous article that perhaps I visited the Island too late in the season and that the end of April would be a better tline to find these species a:s the adults would then be incubating. Revisiting the Island in 1983 proved this to be incorrect. I made three trips in 1983: May 12 , June 11 and June 25. I was sur prised by the lack of tree leaves on May 12. The mainland trees were in leaf but at West Sister no tree bore anything but buds although the v ines and ground cover were in leaf. Perhaps the colder lake temperatures retarded the tree leaf growth. '!be black-crowned night-heron nests contained eggs and newly hatched young. I didn't inspect many nests as this required climbing but I did photograph one nest with four eggs and a second nest with three downy young which I age d at less than five days old (McVaugh, 1973).