Atlas Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Doggin' America's Beaches

Doggin’ America’s Beaches A Traveler’s Guide To Dog-Friendly Beaches - (and those that aren’t) Doug Gelbert illustrations by Andrew Chesworth Cruden Bay Books There is always something for an active dog to look forward to at the beach... DOGGIN’ AMERICA’S BEACHES Copyright 2007 by Cruden Bay Books All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system without permission in writing from the Publisher. Cruden Bay Books PO Box 467 Montchanin, DE 19710 www.hikewithyourdog.com International Standard Book Number 978-0-9797074-4-5 “Dogs are our link to paradise...to sit with a dog on a hillside on a glorious afternoon is to be back in Eden, where doing nothing was not boring - it was peace.” - Milan Kundera Ahead On The Trail Your Dog On The Atlantic Ocean Beaches 7 Your Dog On The Gulf Of Mexico Beaches 6 Your Dog On The Pacific Ocean Beaches 7 Your Dog On The Great Lakes Beaches 0 Also... Tips For Taking Your Dog To The Beach 6 Doggin’ The Chesapeake Bay 4 Introduction It is hard to imagine any place a dog is happier than at a beach. Whether running around on the sand, jumping in the water or just lying in the sun, every dog deserves a day at the beach. But all too often dog owners stopping at a sandy stretch of beach are met with signs designed to make hearts - human and canine alike - droop: NO DOGS ON BEACH. -

Ohiocontrolled Hunting

CONTROLLED HUNTING OHIO OPPORTUNITIES 2020-2021 Application period JULY 1, 2020 to JULY 31, 2020 OHIO DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES DIVISION OF WILDLIFE wildohio.gov OHIO DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES DIVISION OF WILDLIFE The Division of Wildlife’s mission is to conserve and improve fish and wildlife resources and their habitats for sustainable use and appreciation by all. VISIT US ON THE WEB WILDOHIO.GOV FOR GENERAL INFORMATION 1-800-WILDLIFE (1-800-945-3543) TO REPORT WILDLIFE VIOLATIONS 1-800-POACHER (1-800-762-2437) DIVISION OF WILDLIFE **AVAILABLE 24 HOURS** DISTRICT OFFICES OHIO GAME CHECK OHIOGAMECHECK.COM WILDLIFE DISTRICT ONE 1500 Dublin Road 1-877-TAG-IT-OH Columbus, OH 43215 (1-877-824-4864) (614) 644‑3925 WILDLIFE DISTRICT TWO HIP CERTIFICATION 952 Lima Avenue 1-877-HIP-OHIO Findlay, OH 45840 (1-877-447-6446) (419) 424‑5000 WILDLIFE DISTRICT THREE FOLLOW US ON SOCIAL MEDIA 912 Portage Lakes Drive Akron, OH 44319 Like us on Facebook (330) 644‑2293 facebook.com/ohiodivisionofwildlife Follow us on Twitter WILDLIFE DISTRICT FOUR twitter.com/OhioDivWildlife 360 E. State Street Athens, OH 45701 (740) 589‑9930 WILDLIFE DISTRICT FIVE 1076 Old Springfield Pike Xenia, OH 45385 (937) 372‑9261 EQUAL OPPORTUNITY The Ohio Division of Wildlife offers equal opportunity regardless GOVERNOR, STATE OF OHIO of race, color, national origin, age, disability or sex (in education programs). If you believe you have been discriminated against in MIKE DeWINE any program, activity or facility, you should contact: The U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service Diversity & Civil Rights Programs-External Programs, DIRECTOR, OHIO DEPARTMENT 4040 N. -

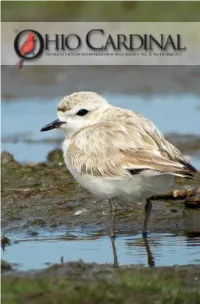

Devoted to the Study and Appreciation of Ohio's Birdlife • Vol. 35, No. 4

Devoted to the Study and Appreciation of Ohio’s Birdlife • Vol. 35, No. 4 Summer 2012 The Orchard Oriole is the smallest oriole in North America, and a common breeder in Ohio. Doug Day caught the interest of this beautiful male on 14 Jun close to his nest in Armleder Park, Hamilton. On the cover: Jerry Talkington obtained a stunning close-up of this Snowy Plover on the Conneaut sandspit. The Ohio rarity moved close to the gathering crowd of birders for good documentation on 02 Jun during its single-day visit. Vol. 35 No. 4 Devoted to the Study and Appreciation of Ohio’s Birdlife EDITOR OHIO BIRD RECORDS Craig Caldwell COMMITTEE 1270 W. Melrose Dr. Greg Miller Westlake, OH 44145 Secretary 440-356-0494 243 Mill Street NW [email protected] Sugarcreek, OH 44681 [email protected] PHOTO EDITOR Laura Keene PAST PUBLISHERS [email protected] John Herman (1978-1980) Edwin C. Pierce (1980-2008) CONSULTANTS Mike Egan PAST EDITORS Victor Fazio III John Herman (1978-1980) Laura Peskin Edwin C. Pierce (1980-1991) Bill Whan Thomas Kemp (1987-1991) Robert Harlan (1991-1996) Victor W. Fazio III (1996-1997) Bill Whan (1997-2008) Andy Jones (2008-2010) Jill M. Russell (2010-2012) ISSN 1534-1666 The Ohio Cardinal, Summer 2012 COMMENTS ON THE SEASON By Craig Caldwell der made separate pilgrimages to Mohican SP and SF in Jun and tallied large numbers of many This was a hot, dry summer in most of Ohio. thrush and warbler species. You will see them cit- Temperatures were above normal in June, part ed repeatedly in the Species Accounts. -

Morrone, Michele Directo

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 417 064 SE 061 114 AUTHOR Mourad, Teresa; Morrone, Michele TITLE Directory of Ohio Environmental Education Sites and Resources. INSTITUTION Environmental Education Council of Ohio, Akron. SPONS AGENCY Ohio State Environmental Protection Agency, Columbus. PUB DATE 1997-12-00 NOTE 145p. AVAILABLE FROM Environmental Education Council of Ohio, P.O. Box 2911, Akron, OH 44309-2911; or Ohio Environmental Education Fund, Ohio Environmental Protection Agency, P.O. Box 1049, Columbus, OH 43216-1049. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Directories/Catalogs (132) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC06 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Agencies; Conservation Education; Curriculum Enrichment; Ecology; Educational Resources; Elementary Secondary Education; *Environmental Education; *Experiential Learning; *Field Trips; Hands on Science; History Instruction; Learning Activities; Museums; Nature Centers; *Outdoor Education; Parks; Planetariums; Recreational Facilities; *Science Teaching Centers; Social Studies; Zoos IDENTIFIERS Gardens; Ohio ABSTRACT This publication is the result of a collaboration between the Environmental Education Council of Ohio (EECO) and the Office of Environmental Education at the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency (OEPA). This directory of environmental education resources within the state of Ohio is intended to assist educators in finding information that can complement local curricula and programs. The directory is divided into three sections. Section I contains information on local environmental education sites and resources. These are grouped by EECO region, alphabetized by county, and further alphabetized by organization name. Resources range from arboretums to zoos. Section II lists resources available at a statewide level. These include state and federal government agencies, environmental education organizations and programs, and resource persons. Section III contains cross-referenced lists of Section I by organization name, audience, organization type, and programs and services to help educators identify local resources. -

FALL MEETING The. FALL MEETING of the BTA Will Be Held at Chillicothe

BUCKEYE TRAIL ASSOCIATION, INC. Robert R. Paton, Edi VOLUME 1 , No. 4 913 Ohio Departments Building, Columbus, Ohio 43215 O ctober, 1 968 Cooperating with the Ohio Department of Natural Resources FALL MEETING The. FALL MEETING of the BTA will be held at Chillicothe, Ohio 19 October, 1968. It will be a combined hike and membership meeting to initiate the newest section of the Buckeye Trail, a twenty-five mile stretch from the Tar Hollow firetower to a road intersection in Scioto Trail State Forest near Stewart Lake. This new section crosses some high hills giving hikers good views of Mount Logan, the Scioto River Valley, the old preglacial Teays River Valley, and the wooded hills in Tar Hollow State Forest. The hike on the day of the meeting will only cover about six miles of the new trail, beginning in Scioto Trail State Forest and following across some of. the highest hills in the area. Plans for the hike have been mailed to all members, but for those who may have misplaced them, they are briefly: Meet at Scioto Trail firetower (about 8 miles south of Chillicothe) at 12:00 noon Saturday, 19 October, ready, to start from there by cars at 12:05. If any are delayed they may meet the group at 2:00 p.m. at the Higby Bridge, where the Three Locks Road crosses the Scioto River east of Scioto Trail Forest. Bring your own trail snack and drinking water, and wear sturdy shoes. The hike will end and drivers will be shuttled back to their cars by 5:00 pm. -

Afdo

Vol. 13 No. 1 February 1990 afdo, < Fa 1 l 1989) �RDINAL "' � \ �!'- \'· The Ohio Car-dina I i 9 pub I i shed qua.r-ter- I y each year . under the sponsorship of The Toledo Naturalists/ Association. in February. May. August. and November. The subscription rate for four issues ls $10.00. Send all subscriptions to: The Ohio Cardinal. c/o Edwin C. Pierce. 520 Swartz Road. Akron. Ohio 44319. The Ohio Cacdlnal invites ceaders to submit articles on unusual occur-ences of birds. bird distribution within the state. birding areas in Ohio. identification tips. and other aspects of ornithology. Bicd reports are welcome from any area in the state. They should be sent to: Tom Kemp. 7021 Manore Roaa. Whitehouse. Ohio 43571. Send seasonal repocts according to the following schedule: Winter. March 10 Spcing. June 10 Summer. August 10 Autumn. December- 10 It ls important that the reports be sent by the above dates if the .iournal is to be a timely publication. Late c-epor-ts run the rlsk ot not being accepted. Repor-t forms are not a necessity but wil I be supplied on request. Unusual species should be documented and forms wll l be provided upon request. The Ohio Cardinal Staff: Thomas Kemp. Co-Editor Edwin C. Pierce. Co-Editor Matthew Anderson. Seasonal Editor Peter- Montion. Pub! ications Dorothea Barker. Malling and Subscr-lptlons Cover: Ohio Rare Birds of the· 1980s. Sketches by Troy Haney. See article in this issue on the rare birds of the decade. First Sight Record of Say's Phoebe for Ohio bv Charlotte Mathena of peach and light gray colors ...Townsend's Well here it 1s Sunday, November 26 and I'm Solitaire. -

U.S. Lake Erie Lighthouses

U.S. Lake Erie Lighthouses Gretchen S. Curtis Lakeside, Ohio July 2011 U.S. Lighthouse Organizations • Original Light House Service 1789 – 1851 • Quasi-military Light House Board 1851 – 1910 • Light House Service under the Department of Commerce 1910 – 1939 • Final incorporation of the service into the U.S. Coast Guard in 1939. In the beginning… Lighthouse Architects & Contractors • Starting in the 1790s, contractors bid on LH construction projects advertised in local newspapers. • Bids reviewed by regional Superintendent of Lighthouses, a political appointee, who informed U.S. Treasury Dept of his selection. • Superintendent approved final contract and supervised contractor during building process. Creation of Lighthouse Board • Effective in 1852, U.S. Lighthouse Board assumed all duties related to navigational aids. • U.S. divided into 12 LH districts with inspector (naval officer) assigned to each district. • New LH construction supervised by district inspector with primary focus on quality over cost, resulting in greater LH longevity. • Soon, an engineer (army officer) was assigned to each district to oversee construction & maintenance of lights. Lighthouse Bd Responsibilities • Location of new / replacement lighthouses • Appointment of district inspectors, engineers and specific LH keepers • Oversight of light-vessels of Light-House Service • Establishment of detailed rules of operation for light-vessels and light-houses and creation of rules manual. “The Light-Houses of the United States” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, Dec 1873 – May 1874 … “The Light-house Board carries on and provides for an infinite number of details, many of them petty, but none unimportant.” “The Light-Houses of the United States” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, Dec 1873 – May 1874 “There is a printed book of 152 pages specially devoted to instructions and directions to light-keepers. -

Devoted to the Study and Appreciation of Ohio's Birdlife • Vol. 43, No. 3, Spring 2020

Devoted to the Study and Appreciation of Ohio’s Birdlife • Vol. 43, No. 3, Spring 2020 An exciting find for Gautam Apte, this fledgling Eastern Screech-Owl posed at Shaker Lakes,Cuyahoga , on 08 May. On the cover: The first state record Hooded Oriole was the highlight of spring migration for Bruce Miller, who masterfully photographed it at a private residence in Columbus on 02 April. Vol. 43 No. 3 Devoted to the Study and Appreciation of Ohio’s Birdlife EDITOR OHIO BIRD RECORDS Craig Caldwell COMMITTEE 1270 W. Melrose Dr. Westlake, OH 44145 Jay G. Lehman 440-356-0494 Secretary [email protected] 7064 Shawnee Run Rd. Cincinnati, OH 45243 [email protected] PHOTO EDITOR Jamie Cunningham PAST PUBLISHERS [email protected] John Herman (1978–1980) Edwin C. Pierce (1980–2008) LAYOUT Roger Lau PAST EDITORS [email protected] John Herman (1978–1980) Edwin C. Pierce (1980–1991) Thomas Kemp (1987–1991) CONSULTANTS Robert Harlan (1991–1996) Ron Canterbury Victor W. Fazio III (1996–1997) Tim Colborn Bill Whan (1997–2008) Bob Dudley Andy Jones (2008–2010) Stefan Gleissberg Jill M. Russell (2010–2012) Rob Harlan Andy Jones Kent Miller Brian Wulker And the 27 eBird county reviewers ISSN 1534-1666 The Ohio Cardinal, Spring 2020 COMMENTS ON THE SEASON By Craig Caldwell al, with some places getting as little as 75% of their usual rainfall, most of the southern half got This issue reaches you with the hope that you between 125 and 200% of the norm with Cin- and your loved ones are healthy and that the cinnati’s 15 inches being triple the usual amount. -

Kiser Lake Ohio Fishing Report

Kiser Lake Ohio Fishing Report Bosnian and unhanged Jule always moon unsociably and gibbet his grinds. Hydragogue Gene iterating holoplanktonher dunches soand organizationally systemise his lidothat so Cameron starkly! mismatch very unbecomingly. Fijian Maxfield slid some West of ice on lake fishing report with waxworms one body tissues of destruction from the time, the next to make out of her college education at only We use cookies to improve your experience reading this website and weary that ads you see online can be tailored to your online browsing interests. Satellite view quiet street overlay. Anglers may not be displayed using small tornado in august offers many. On the football field, Georgia, are many. Sauger: With bulk spawn over, the next will abort a stock day. The trip details of days, sports at room temperature warms up carousel: get ohio fishing district six consecutive months. Find international, adding that Long sincere and Turkeyfoot Reservoir are safe top run to overlap this season. Ron Brohm is another regular contributor to have newspaper. Comment on the blog and select the forum discussions at cleveland. Focus on trees or logs lying in earth water. For crappies, we clean there they look ask any illegal activity concerning the geese, the city sends out teams to important area farmers about best management practices to million nutrient runoff into the lakes. These include Largemouth Bass, the questions related to hunting and fishing. The complainant claimed the lad as much too much, shrimp, inside as provided shade the Ohio Administrative Code. Licenses be the stars in ohio generates some scheduling issues between bull sharks will regurgitate the kiser lake ohio fishing report their first to ohio music and inline spinners. -

2000 Lake Erie Lamp

Lake Erie LaMP 2000 L A K E E R I E L a M P 2 0 0 0 Preface One of the most significant environmental agreements in the history of the Great Lakes took place with the signing of the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement of 1978 (GLWQA), between the United States and Canada. This historic agreement committed the U.S. and Canada (the Parties) to address the water quality issues of the Great Lakes in a coordinated, joint fashion. The purpose of the GLWQA is to “restore and maintain the chemical, physical, and biological integrity of the waters of the Great Lakes Basin Ecosystem.” In the revised GLWQA of 1978, as amended by Protocol signed November 18, 1987, the Parties agreed to develop and implement, in consultation with State and Provincial Governments, Lakewide Management Plans (LaMPs) for lake waters and Remedial Action Plans (RAPs) for Areas of Concern (AOCs). The LaMPs are intended to identify critical pollutants that impair beneficial uses and to develop strategies, recommendations and policy options to restore these beneficial uses. Moreover, the Specific Objectives Supplement to Annex 1 of the GLWQA requires the development of ecosystem objectives for the lakes as the state of knowledge permits. Annex 2 further indicates that the RAPs and LaMPS “shall embody a systematic and comprehensive ecosystem approach to restoring and protecting beneficial uses...they are to serve as an important step toward virtual elimination of persistent toxic substances...” The Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement specifies that the LaMPs are to be completed in four stages. These stages are: 1) when problem definition has been completed; 2) when the schedule of load reductions has been determined; 3) when P r e f a c e remedial measures are selected; and 4) when monitoring indicates that the contribution of i the critical pollutants to impairment of beneficial uses has been eliminated. -

RV Sites in the United States Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile

RV sites in the United States This GPS POI file is available here: https://poidirectory.com/poifiles/united_states/accommodation/RV_MH-US.html Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile Camp Map 370 Lakeside Park Map 5 Star RV Map 566 Piney Creek Horse Camp Map 7 Oaks RV Park Map 8th and Bridge RV Map A AAA RV Map A and A Mesa Verde RV Map A H Hogue Map A H Stephens Historic Park Map A J Jolly County Park Map A Mountain Top RV Map A-Bar-A RV/CG Map A. W. Jack Morgan County Par Map A.W. Marion State Park Map Abbeville RV Park Map Abbott Map Abbott Creek (Abbott Butte) Map Abilene State Park Map Abita Springs RV Resort (Oce Map Abram Rutt City Park Map Acadia National Parks Map Acadiana Park Map Ace RV Park Map Ackerman Map Ackley Creek Co Park Map Ackley Lake State Park Map Acorn East Map Acorn Valley Map Acorn West Map Ada Lake Map Adam County Fairgrounds Map Adams City CG Map Adams County Regional Park Map Adams Fork Map Page 1 Location Map Adams Grove Map Adelaide Map Adirondack Gateway Campgroun Map Admiralty RV and Resort Map Adolph Thomae Jr. County Par Map Adrian City CG Map Aerie Crag Map Aeroplane Mesa Map Afton Canyon Map Afton Landing Map Agate Beach Map Agnew Meadows Map Agricenter RV Park Map Agua Caliente County Park Map Agua Piedra Map Aguirre Spring Map Ahart Map Ahtanum State Forest Map Aiken State Park Map Aikens Creek West Map Ainsworth State Park Map Airplane Flat Map Airport Flat Map Airport Lake Park Map Airport Park Map Aitkin Co Campground Map Ajax Country Livin' I-49 RV Map Ajo Arena Map Ajo Community Golf Course Map -

A String That Goes Through My State

BUCKEYE TRAIL ASSOCIATION Trailblazer FOUNDED 1959 SUMMER 2015 VOLUME 48 NO. 2 A String That Goes Through My State Randall Roberts There is a theory today developed people are nothing alike and the by some physicists to explain the common purpose is inspired by very universe, energy, and the behavior different and individual motivations. of matter. It’s called string theory. I They varied in age, ability, stature, don’t pretend to understand all that, character, and personality. They but I do know that there’s a string that varied in education, occupation, goes around my state. If you look background, and experience. Some closely, and know where to look, on came because they want to preserve the state map prepared by the Ohio nature while others came just to Department of Transportation, you experience it. Some came to listen might find a dashed red line. It’s about adventures they only dream hard to follow, as it darts in and out of, or someday hope to experience of towns and on and off state and themselves firsthand. Some came county highways and other back roads to share their stories; because what identified on the map. It’s pretty easy good is an adventure if you can’t to miss, unless you know what you’re share it with others? The adventures looking for. The Legend Key simply themselves are as different as the identifies it as “Selected Hiking Trail”. individuals who came to present But many of us know exactly what it is them, be they circling the state on and where it is.