Changes in Landscape Structure in the Municipalities of the Nitra District (Slovak Republic) Due to Expanding Suburbanization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tabuľka Výsledkov Testovania Miest a Obcí (2., 3. a 4. Kolo) + Porovnanie Kraj Okres Obec 2 Etapa 30.10.-1.11

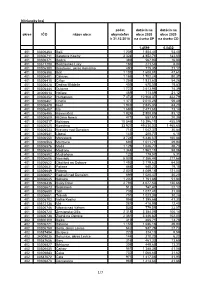

Tabuľka výsledkov testovania miest a obcí (2., 3. a 4. kolo) + porovnanie Kraj Okres Obec 2 etapa 30.10.-1.11. 3 etapa 7.-8.11. 4 etapa 21.-22.11. rezidentní 4 etapa 21.-22.11. nerezident 4 etapa 21.-22.11. spolu test poz % poz test poz % poz test poz % poz test poz % poz test poz % poz Banskobystrický Banská Bystrica Baláže 170 4 2,35% 196 2 1,02% 54 0 0,00% 63 3 4,76% 117 3 2,56% Banskobystrický Banská Štiavnica Kozelník 95 2 2,11% 18 0 0,00% 30 2 6,67% 48 2 4,17% Banskobystrický Banská Štiavnica Močiar 97 1 1,03% 20 0 0,00% 16 0 0,00% 36 0 0,00% Banskobystrický Brezno Dolná Lehota 788 5 0,63% 707 8 1,13% 131 0 0,00% 36 0 0,00% 167 0 0,00% Banskobystrický Brezno Jasenie 655 12 1,83% 719 8 1,11% 265 4 1,51% 46 1 2,17% 311 5 1,61% Banskobystrický Brezno Šumiac 790 9 1,14% 842 10 1,19% 166 8 4,82% 70 2 2,86% 236 10 4,24% Banskobystrický Brezno Valaská 1829 31 1,69% 1905 21 1,10% 396 11 2,78% 79 3 3,80% 475 14 2,95% Banskobystrický Brezno Vaľkovňa 341 3 0,88% 349 5 1,43% 22 0 0,00% 58 6 10,34% 80 6 7,50% Banskobystrický Krupina Hontianske Moravce 421 6 1,43% 120 2 1,67% 22 0 0,00% 142 2 1,41% Banskobystrický Krupina Ladzany 337 4 1,19% 53 0 0,00% 13 0 0,00% 66 0 0,00% Banskobystrický Krupina Lišov 146 2 1,37% 81 3 3,70% 21 0 0,00% 102 3 2,94% Banskobystrický Krupina Súdovce 166 2 1,20% 50 0 0,00% 18 0 0,00% 68 0 0,00% Banskobystrický Lučenec Mikušovce 163 2 1,23% 42 0 0,00% 67 2 2,99% 109 2 1,83% Banskobystrický Lučenec Mýtna 842 15 1,78% 76 1 1,32% 197 22 11,17% 273 23 8,42% Banskobystrický Poltár Hradište 144 2 1,39% 10 0 0,00% 5 0 0,00% -

Mesačný Výkaz Prenosných Ochorení Za Mesiac M Á J 2018 V Okrese Nitra

Mesačný výkaz prenosných ochorení za mesiac m á j 2018 v okrese Nitra Analýza infekčných ochorení podľa miesta výskytu: A02 - 1 Vylučovanie salmonel – Nitra 1 A02.0 - 28 Salmonelová enteritída – Alekšince 1, Jarok 1, Luţianky 3, Nitra 16, Nitrianske Hrnčiarovce 1, Pohranice 1, Veľký Lapáš 2, Vráble 1, Výčapy Opatovce 1, Ţirany 1 A04.0 - 1 Infekcia vyvolaná enteropatogénnymi E.coli – Čeľadice 1 A04.5 - 13 Kampylobakterióza – Alekšince 1, Báb 1, Malý Lapáš 1, Melek 1, Nitra 6, Vráble 1, Výčapy Opatovce 1, Ţirany 1 A04.7 - 10 Enterokolitída zapríčinená Clostridium difficile – Čechynce 1, Luţianky 1, Nitra 8 A08.0 - 10 Rotavírusová enteritída – Ivanka pri Nitre 1, Jelšovce 1, Kolíňany 1, Lehota 1, Nitra 4, Rišňovce 1, Veľký Lapáš 1 A08.1 - 13 Akútna gastroenteropatia zapríčinená vírusom Norwalk – Alekšince 1, Cabaj-Čápor 1, Ivanka pri Nitre 1, Jelšovce 1, Nitra 9 A08.2 - 3 Adenovírusová enteritída – Jelšovce 1, Kolíňany 1, Nitrianske Hrnčiarovce 1 A38 - 2 Šarlach – Golianovo 1, Nitra 1 A40.1 - 1 Septikémia vyvolaná streptokokom zo skupiny B – Čakajovce 1 A41.5 - 1 Septikémia vyvolaná inými špecifikovanými stafylokokmi – Nitra 1 A46 - 2 Ruţa – erysipelas – Nitra 1, Šurianky 1 A51.0 - 2 Primárny genitálny syfilis – Nitra 2 A53.0 - 1 Latentný syfilis nešpecifikovaný ako včasný alebo neskorý – Nitra 1 A54.0 - 1 Gonokoková infekcia – Nitra 1 A69.2 - 1 Lymská borelióza – Veľká Dolina 1 A84.1 - 1 Stredoeurópska kliešťová encefalitída – Nitra 1 A86 - 1 Nešpecifikovaná vírusová meningoencefalitída – Nitra 1 A98.5 - 1 Hemoragická horúčka s renálnym -

GEODETICKÝ a KARTOGRAFICKÝ ÚSTAV BRATISLAVA Chlumeckého 4, 827 45 Bratislava II

GEODETICKÝ A KARTOGRAFICKÝ ÚSTAV BRATISLAVA Chlumeckého 4, 827 45 Bratislava II Register katastrálnych území Posledná aktualizácia: marec 2021 Okres Obec Katastrálne územie Identifikátor ID Vymera Pracovné Kód Názov Kód Názov Kód Názov Skratka katastr. 2 číslo (m ) pracoviska 1 101 Bratislava I 528595 Bratislava-Staré Mesto 804096 9590124 Staré Mesto SM 16 109 2 102 Bratislava II 529311 Bratislava-Podunajské Biskupice 847755 42492968 Podunajské Biskupice PB 20 109 3 102 Bratislava II 529320 Bratislava-Ružinov 804274 7412531 Nivy NI 27 109 4 102 Bratislava II 529320 Bratislava-Ružinov 805556 19362159 Ružinov RZ 21 109 5 102 Bratislava II 529320 Bratislava-Ružinov 805343 12925730 Trnávka TR 19 109 6 102 Bratislava II 529338 Bratislava-Vrakuňa 870293 10296679 Vrakuňa VR 17 109 7 103 Bratislava III 529346 Bratislava-Nové Mesto 804690 9852704 Nové Mesto NM 26 109 8 103 Bratislava III 529346 Bratislava-Nové Mesto 804380 27628780 Vinohrady VI 13 109 9 103 Bratislava III 529354 Bratislava-Rača 805866 23659304 Rača RA 25 109 10 103 Bratislava III 529362 Bratislava-Vajnory 805700 13534087 Vajnory VA 29 109 11 104 Bratislava IV 529401 Bratislava-Devín 805301 14007658 Devín DE 28 109 12 104 Bratislava IV 529371 Bratislava-Devínska Nová Ves 810649 24217253 Devínska Nová Ves DV 14 109 13 104 Bratislava IV 529389 Bratislava-Dúbravka 806099 8648836 Dúbravka DU 11 109 14 104 Bratislava IV 529397 Bratislava-Karlova Ves 805211 10951096 Karlova Ves KV 10 109 15 104 Bratislava IV 529419 Bratislava-Lamač 806005 6542373 Lamač LA 12 109 16 104 Bratislava IV -

Odpočtový Obvod Bánovce Nad Bebravou Ročný Odpočet Obec

Odpočtový obvod Bánovce nad Bebravou Ročný odpočet Obec, časť obce Jan. Feb. Mar. Apr. Máj Jún Júl Aug. Sep. Okt. Nov. Dec. Bánovce nad Bebravou Biskupice Bor čany Brodzany Dežerice Dolné Naštice Dolné Ozorovce Dubni čka Dvorec Halá čovce Horné Chlebany Horné Naštice Horné Ozorovce Hradište Chudá Lehota Chynorany Ješkova Ves Kola čno Krásna Ves Krásno Krušovce Krušovce - D.Chlebany Kšinná Libichava Livinské Opatovce Ľutov Malé Bielice Malé Chlievany Malé Kršte ňany Malé Uherce Nadlice Návojovce Nedanovce Nedašovce Norovce Omastiná Ostratice Otrhánky Partizánske Paži ť Pe čeňany Podlužany Pravotice Prusy Raj čany Ruskovce Rybany Ska čany Slatina nad Bebravou Slatinka nad Bebravou Sol čianky Šípkov Šišov Timoradza Tur čianky Uhrovec Uhrovské Podhradie Ve ľké Bielice Ve ľké Chlievany Ve ľké Kršte ňany Ve ľké Uherce Závada pod Čier.Vrchom Žabokreky nad Nitrou Žitná-Radiša Odpočtový obvod Topoľčany Ročný odpočet Obec, časť obce Jan. Feb. Mar. Apr. Máj Jún Júl Aug. Sep. Okt. Nov. Dec. Ardanovce 76 Belince 76 Biskupová 67 Bojná Bojná - Malé Dvorany Bošany Bzince Čeľadince Čermany Duchonka - chaty Dvorany nad Nitrou H.Obdokovce - Obsolovce Hajná Nová Ves Horné Obdokovce Horné Štitáre Chrabrany Jacovce Kamanová Kapince Klížske Hradište Kovarce Krtovce Kuzmice Ludanice Lužany Malé Bedzany Malé Rip ňany Mýtna Nová Ves Nem čice Nitrianska Blatnica Nitrianska Streda Oponice Podhradie Prašice Práznovce Prese ľany Radošina Sol čany Súlovce Svrbice Šalgovce Tesáre Topo ľčany Tovarníky Tvrdomestice Ve ľké Bedzany Ve ľké Dvorany Ve ľké Rip ňany Ve ľké Rip ňany - Behynce Ve ľký Klíž Velušovce Vozokany Závada Závada - Záhrada Odpočtový obvod Nitra Ročný odpočet Obec, časť obce Jan. Feb. Mar. Apr. -

Mesačný Výkaz Prenosných Ochorení Za Mesiac F E B R U Á R 2021 V Okrese Nitra

Mesačný výkaz prenosných ochorení za mesiac f e b r u á r 2021 v okrese Nitra Analýza infekčných ochorení podľa miesta výskytu: A02.0 - 5 Salmonelová enteritída – Mojmírovce 1, Nitra 1, Veľký Cetín 1, Vráble 2 A04.5 - 3 Kampylobakterióza – Báb 1, Babindol 1, Nitra 1 A04.7 - 54 Enterokolitída zapríčinená Clostridium difficile – Hruboňovo 1, Ivanka pri Nitre 1, Nitra 51, Žitavce 1 A08.1 - 1 Akútna gastroenteropatia vyvolaná vírusom Norwalk – Nitra 1 A15.0 - 1 Tuberkulóza pľúc potvrdená mikroskopiou spúta – Alekšince 1 A41.1 - 2 Septikémia vyvolaná inými stafylokokmi (nenozokomiálna) – Nitra 2 A54.0 - 2 Gonokoková infekcia – Nitra 2 A98.5 - 2 Hemoragická horúčka s renálnym syndrómom – Kolíňany 1, Nitra 1 B00.9 - 1 Nešpecifikovaná herpetickovírusová infekcia – Nitra 1 B01.9 - 2 Varicella bez komplikácie – Babindol 1, Lukáčovce 1 B02.0 - 1 Zosterová meningoencefalitída – Nitra 1 B02.9 - 2 Zoster bez komplikácie – Lužianky 1, Nitra 1 B86 - 8 Svrab – Mojmírovce 2, Nitra 6 G04.9 - 1 Nešpecifikovaná encefalitída, myelitída a encefalomyelitída – Veľké Zálužie 1 U07.1 - 929 Covid-19 potvrdený PCR – Alekšince 20, Báb 5, Babindol 1, Bádice 1, Branč 14, Cabaj-Čápor 30, Čab 8, Čakajovce 6, Čeľadice 5, Čechynce 3, Dolné Lefantovce 7, Dolné Obdokovce 3, Golianovo 8, Horné Lefantovce 14, Hosťová , Hruboňovo 6, Ivanka pri Nitre 18, Jarok 18, Jelenec 9, Jelšovce 6, Kapince 1, Klasov 1, Kolíňany 8, Lehota 16, Lúčnica nad Žitavou 3, Ľudovítová 3, Lukáčovce 17, Lužianky 19, Malé Zálužie 4, Malý Cetín 1, Malý Lapáš 10, Melek 3, Mojmírovce 19, Nitra 420, Nitrianske -

Neoficiálne Výsledky 2018.Xlsx

č.v. Odroda Ročník Prívl. Meno Adresa Body 1 Zmes Biela 2017 kab Bako Vladimír Jarok 744 84,00 2 Zmes Biela 2017 Bédy Karol Jarok 557 72,67 3 Zmes Biela 2017 Bekény Juraj Pod Cintorínom 628/29, Jarok 73,33 4 Zmes Biela 2017 Chňapek Dezider Jarok 466 70,67 5 Zmes Biela 2017 Chňapek Jozef Veľké Zálužie 1129 75,00 6 Zmes Biela 2017 Cítenyi Daniel Lehota 110 83,33 7 Zmes Biela 2017 Cocher Ján Veľké Zálužie 1473 85,33 8 Zmes Biela 2017 Ďurfina Štefan Jarok 200 72,00 9 Zmes Biela 2017 Fuglík Stanislav Jarok 85/90 78,67 10 Zmes Biela 2017 Gergeľ Jozef, Richter Ivan Jarok 78,00 11 Zmes Biela (Dev+TC) 2016 NZ Kakalík Marek Šenkvice 83,33 12 Zmes Biela 2017 Komarňanský Roman, Ing. Veľké Zálužie 178 85,33 Zmes Biela (Bianka + 13 RŠ) 2017 Kováč Róbert Nová Ves n. Žitavou 282 75,33 14 Zmes Biela 2017 Lámoš Marián Jarok 429/84 80,33 15 Zmes Biela 2017 Lenčéš Bohuslav Chalupy 146, Močenok 88,00 16 Zmes Biela 2017 Ligač Jozef Cabaj-Čápor 1401 77,33 17 Zmes Biela 2017 Melo Jaroslav st. Pod vinohradmi 458, Jarok 81,33 18 Zmes Biela 2017 Molnár Ladislav Jelenec 71,00 Pod Vinohradmi 450/17, 19 Zmes Biela 2017 kab Nota Milan Jarok 86,00 20 Zmes Biela 2016 Oravský Igor Hronského 4, Lužianky 74,67 21 Zmes Biela 2017 Oravský Jozef Pod Hliníkom 8, Lužianky 76,00 22 Zmes Biela 2017 kab Pápay Peter Močenok 86,00 23 Zmes Biela 2017 Pavel Štefan Lehota 355 83,67 24 Zmes Biela 2017 Petrík Štefan Lehota 301 78,00 25 Zmes Biela 2017 Petrík Štefan Lehota 301 78,33 26 Zmes Biela 2017 Ridzoň Ivan Chalupy 130, Močenok 88,00 27 Zmes Biela 2017 Rodina Hrnková Štepnice 1, Jarok 81,00 28 Zmes Biela 2017 Snovák Daniel Cabaj-Čápor 585 84,00 29 Zmes Biela 2017 Šponiar Peter, Ing. -

Historické Parky a Záhrady Okresu Nitra

HISTORICKÉ PARKY A ZÁHRADY OKRESU NITRA Richard Kubišta Katedra záhradnej a krajinnej architektúry, Fakulta záhradníctva a krajinného inžinierstva SPU v Nitre, Tulipánová 7, 949 76 Nitra, e-mail: [email protected] Abstract Historical Parks and Gardens of Nitra District After the change of the political system in 1989 it came to a reevaluation of the relation to the cultural and historical heritage of the society. Today are historical parks and gardens an important part of national monuments of each nation. Nitra District is specific by a fact that there is an historical park or garden in almost each village. In the past it was usually a residence of the nobility or of the land lords. Each of them needed to represent themselves by larger or smaller manor house together with park or garden. Theoretical research has shown that such historical objects are to found in villages: Nová Ves nad Žitavou, Mojmírovce, Lefantovce, Tajná, Nitra-Kynek, Dolná Malanta (Nitrianske Hrnčiarovce), Lúčnica nad Žitavou, Veľké Zálužie, Báb, Rišňovce, Klasov, Jelenec, Výčapy-Opatovce a Ľudovítová. Their condition, area and period-style is various, even their present use, but they have one thing in common – they decline. Field research was oriented on their photo documentation, on the evaluation of their condition and on categorisation based on possible use in these times. Reconstruction of buildings – manor houses is little bit simplier then the reconstruction of gardens or parks. It is because it needs much more time to achieve compareable result and it requires continual maintenance. Of course the result is conditioned by the spoting of a new meanigful reason for their exitence. -

Kronika Mesta Nitry 2017 K R O N I K a M E S T a N I T R Y

KRONIKA MESTA NITRY 2017 K R O N I K A M E S T A N I T R Y Zápis za rok 2017 Nitriansky kraj Okres Nitra Napísala: Mgr. Ľudmila Synaková kronikárka mesta Nitry 1 KRONIKA MESTA NITRY 2017 2 KRONIKA MESTA NITRY 2017 Zápis do Kroniky mesta Nitry obsahuje 352 strán textu (slovom tristopäťdesiatdva strán) a má 15 kapitol ⫸⫷ Zápis schválila komisia pre kultúru, cestovný ruch a zahraničné vzťahy pri Mestskom zastupiteľstve v Nitre na svojom zasadnutí dňa 24. septembra 2018 Zápis schválila Mestská rada v Nitre na svojom zasadnutí 17. decembra 2018 JUDr. Igor Kršiak Marek Hattas prednosta Mestského úradu v Nitre primátor mesta Nitry 3 KRONIKA MESTA NITRY 2017 OBSAH ÚVOD.......................................................................................................................................................................7 1. OBYVATEĽSTVO ......................................................................................................................................10 1.1 Demografické a iné údaje...............................................................................................................10 1.2 Ocenenia a vyznamenania osobností........................................................................................13 1.3 Úmrtia významných osobností ...................................................................................................16 2. MESTSKÁ SAMOSPRÁVA......................................................................................................................20 2.1 Rozpočet mesta Nitry -

Zoznam Verejných Obstarávateľov Pristupujúcich K VO

Zoznam verejných obstarávateľov pristupujúcich k verejnému obstarávaniu Názov zákazky: Príležitostné spoločné verejné obstarávanie elektrickej energie - Nitrianske regionálne združenie obcí - ZMOS Názov verejného obstarávateľa: Nitrianske regionálne združenie obcí - ZMOS Sídlo: Obecný úrad Jelšovce č. 37, 951 43 Jelšovce Názov verejných Por. Sídlo verejných obstarávateľov Štatutárny zástupca E-mailová adresa obstarávateľov IČO č. pristupujúcich k VO pristupujúcich k VO Tel. kontakt Internetová stránka Ing. Ivan Patoprstý [email protected] 1. Obec Báhoň SNP 65, 900 84 Báhoň 00304654 336455193 www.bahon.sk PhDr. Jozef Savkuliak [email protected] 2. Obec Budmerice J. Rašu 534, 900 86 Budmerice 00304697 336448104 www.budmerice.sk Jozef Mikuška [email protected] 3. Obec Čab č. 1, 951 24 Nové Sady 36105724 377894388 www.obeccab.sk Ing. Anton Laca [email protected] 4. Obec Čeľadice č. 143, 951 03 Čeľadice 00307831 377877221 www.celadice.webnode.sk Farská ulica 25/13, 951 45 Horné Ing. Martin Cibula [email protected] 5. Obec Horné Lefantovce 00399418 Lefantovce 377786356 www.hornelefantovce.sk Ladislav Hroššo [email protected] 6. Obec Jelšovce č. 37, 951 43 Jelšovce 00308081 377893001 www.jelsovce.sk Ján Balázs [email protected] 7. Obec Klasov č. 108, 951 53 Klasov 00308102 377883011 www.klasov.sk Nám. L. A. Aranya 528, 951 78 Ing. Róbert Balkó [email protected] 8. Obec Kolíňany 00308111 Kolíňany 376316220 www.kolinany.eu Bc. Adriana Čechovičová [email protected] 9. Obec Limbach SNP 55, 900 91 Limbach 00304891 336477221 www.obec-limbach.sk Mgr. Ján Ferus [email protected] 10. Obec Melek č. 250, 952 01 Vráble 00308251 377882259 www.melek.sk RNDr. -

Miestne Akčné Skupiny Typu Leader V Nitrianskom Samosprávnom Kraji Miestne Akčné Skupiny Typu Leader Na Území Nitrianskeho Samosprávneho Kraja

MIESTNE AKČNÉ SKUPINY TYPU LEADER V NITRIANSKOM SAMOSPRÁVNOM KRAJI MIESTNE AKČNÉ SKUPINY TYPU LEADER NA ÚZEMÍ NITRIANSKEHO SAMOSPRÁVNEHO KRAJA DOLNÁ NITRA DOLNÁ NITRA DOLNÁ NITRA DOLNÁ NITRA (Poľný Kesov) MIKRO HURBANOVOREGIÓN 2 NITRIANSKY SAMOSPRÁVNY KRAJ PODPORUJE ROZVOJ VIDIEKA A INOVATÍVNE PROJEKTY MIESTNYCH AKČNÝCH SKUPÍN 3 MIESTNA AKČNÁ SKUPINA TYPU LEADER SOTDUM Názov občianskeho združenia Zoznam obcí v území MAS Web stránka Sídlo združenia Kontakt Prašice, Jacovce, Tovarníky, Miestna akčná skupina Krušovce, Nemčice, Kuzmice, Tesáre, Spoločenstva obcí Velušovce, Závada, Podhradie, http://www.sotdum.sk/ Prašice [email protected] topoľčiansko - duchonského Tvrdomestice, Nemečky, Solčianky, mikroregiónu Norovce, Rajčany, Horné Chlebany Premena parku v centre obce na miesto života – Šach na pódiu – Zelené námestie 1. časť Rekonštrukcia sochy stretnutí, dišpút, oddychu a relaxu (Obec Velušovce) (Obec Tesáre) Sv. Jána Nepomuckého (Občianska iniciatíva Sv. Ján Nepomucký) 4 MIESTNA AKČNÁ SKUPINA TYPU LEADER SVORNOSŤ Názov občianskeho združenia Zoznam obcí v území MAS Web stránka Sídlo združenia Kontakt Belince, Čeľadince, Čermany, Dvorany nad Nitrou, Horné Obdokovce, Združenie mikroegiónu Hrušovany, Chrabrany, Kamanová, http://www.mrsvornost.sk/ Chrabrany [email protected] SVORNOSŤ Koniarovce, Krnča, Ludanice, Nitrianska Streda, Práznovce, Preseľany, Oponice, Solčany, Súlovce, Kovarce Architektonická štúdia – Detské ihrisko pri KD Krnča Architektonická štúdia Výstavba detského ihriska Projektová dokumentácia Prestavba (Obec Krnča) -

Skupinový Vodovod Nitra Ktorý Zásobuje Spotrebiská

K 31.12.2018 evidujeme tieto vodovody : skupinový vodovod Nitra ktorý zásobuje spotrebiská : Nitra a Čechynce skupinový vodovod Nitra – Šaľa zásobuje spotrebiská Cabaj -Čápor, Mojmírovce, Ivanka pri Nitre, Luţianky, Svätoplukovo, Lehota, Branč, Veľké Záluţie, Jarok, Zbehy, Šaľa, Diakovce, Kráľová n/Váhom, Dlhá n/Váhom, Trnovec n/Váhom, Močenok a Horná Kráľová diaľkovod Gabčíkovo – zásobuje spotrebiská Vráble, Melek, Veľké a Malé Chyndice, Telince, Nová Ves nad Ţitavou, Tajná, Čifáre, Ţitavce, Lúčnica nad Ţitavou, Paňa, Vinodol, Klasov, Vieska n/Ţitavou, Slepčany, Tesárske Mlyňany, Čierne Kľačany, Volkovce, Choča, Beladice, Čaradice, Sľaţany, Zlaté Moravce, Veľčice, Zlatno, Nemčiňany, Topoľčianky, Ţitavany, Tekovské Nemce, Červený Hrádok, Malé a Veľké Vozokany, Nevidzany, Selice, Vlčany, Neded, Ţihárec a Tešedíkovo, Veľký a Malý Cetín skupinový vodovod Kolíňany – zásobuje spotrebiská Kolíňany, Hosťová, Dolné Obdokovce, Čeľadice, Golianovo, Malý a Veľký Lapáš, Babindol skupinový vodovod Radošina – Veľké Ripňany zásobuje spotrebiská Kapince, Malé Záluţie Ponitriansky skupinový vodovod – zásobuje spotrebiská Výčapy-Opatovce, Ľudovítová, Čakajovce, Nitrianske Hrnčiarovce, Horné a Dolné Lefantovce a Jelšovce vodovody zásobované z vlastných vodných zdrojov v obciach Alekšince, Štefanovičová, Nové Sady, Nitra – mestská časť Dráţovce, Lukáčovce, Podhorany, ktorý v súčasnosti zásobuje aj obec Bádice, Veľká Dolina, Poľný Kesov, Jelenec, Rumanová, Báb, Ţirany, Rišňovce, Pohranice, Štitáre, Hruboňovo, ktorý zásobuje aj obec Šurianky, Nové Sady - Sila, ktorý zásobuje aj obec Čab, Hostie, Mankovce, Jedľové Kostoľany, Lovce, Machulince, Martin nad Ţitavou, Skýcov, Obyce, z časti obec Topoľčianky a Hájske. Pre vodárenské účely sú vo všetkých troch okresoch vyuţívané len zdroje podzemných vôd väčšinou v správe ZsVSa.s, Nitra, ZsVs OZ Galanta, ZsVS OZ Topoľčany. Prevádzku vodovodov zabezpečujú pre obce tieţ Ekostaving Nitra, Vodárenská správcovská spoločnosť Mojmírovce, s.r.o., Mojmírovce, AquaVita Plus, s.r.o. -

Nitriansky Kraj Okres IČO Názov Obce Počet Obyvateľov K 31.12.2018

Nitriansky kraj počet dotácia na dotácia na okres IČO názov obce obyvateľov obce 2020 obce 2020 k 31.12.2018 na úseku SP na úseku CD 1,4599 0,0432 401 00306363 Bajč 1 236 1 804,44 53,40 401 00306711 Bátorove Kosihy 3 324 4 852,71 143,60 401 00306371 Bodza 389 567,90 16,80 401 00611298 Bodzianske Lúky 186 271,54 8,04 401 00306380 Brestovec, okres Komárno 490 715,35 21,17 401 00306398 Búč 1 102 1 608,81 47,61 401 00306401 Čalovec 1 166 1 702,24 50,37 401 00306410 Číčov 1 256 1 833,63 54,26 401 00306428 Dedina Mládeže 459 670,09 19,83 401 00306444 Dulovce 1 722 2 513,95 74,39 401 34006613 Holiare 489 713,89 21,12 401 00306452 Hurbanovo 7 472 10 908,37 322,79 401 00306461 Chotín 1 377 2 010,28 59,49 401 00306479 Imeľ 1 949 2 845,35 84,20 401 00306487 Iža 1 693 2 471,61 73,14 401 00306495 Kameničná 1 924 2 808,85 83,12 401 00306509 Klížska Nemá 471 687,61 20,35 401 00306517 Kolárovo 10 546 15 396,11 455,59 401 00306525 Komárno 33 927 49 530,03 1 465,65 401 00306533 Kravany nad Dunajom 714 1 042,37 30,84 401 00306541 Lipové 143 208,77 6,18 401 00306550 Marcelová 3 724 5 436,67 160,88 401 00306568 Martovce 693 1 011,71 29,94 401 00306576 Moča 1 128 1 646,77 48,73 401 00306584 Modrany 1 344 1 962,11 58,06 401 00306592 Mudroňovo 123 179,57 5,31 401 00306606 Nesvady 5 039 7 356,44 217,68 401 00306622 Okoličná na Ostrove 1 493 2 179,63 64,50 401 00306631 Patince 444 648,20 19,18 401 00306649 Pribeta 2 801 4 089,18 121,00 401 00306657 Radvaň nad Dunajom 699 1 020,47 30,20 401 00306665 Sokolce 1 200 1 751,88 51,84 401 00306436 Svätý Peter 2 793 4 077,50