Virtually Splitting Data Caches Using Multiple Address Decoders

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Intel ® Atom™ Processor E6xx Series SKU for Different Segments” on Page 30 Updated Table 15

Intel® Atom™ Processor E6xx Series Datasheet July 2011 Revision 004US Document Number: 324208-004US INFORMATIONLegal Lines and Disclaimers IN THIS DOCUMENT IS PROVIDED IN CONNECTION WITH INTEL® PRODUCTS. NO LICENSE, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, BY ESTOPPEL OR OTHERWISE, TO ANY INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY RIGHTS IS GRANTED BY THIS DOCUMENT. EXCEPT AS PROVIDED IN INTEL’S TERMS AND CONDITIONS OF SALE FOR SUCH PRODUCTS, INTEL ASSUMES NO LIABILITY WHATSOEVER, AND INTEL DISCLAIMS ANY EXPRESS OR IMPLIED WARRANTY, RELATING TO SALE AND/OR USE OF INTEL PRODUCTS INCLUDING LIABILITY OR WARRANTIES RELATING TO FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE, MERCHANTABILITY, OR INFRINGEMENT OF ANY PATENT, COPYRIGHT OR OTHER INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY RIGHT. UNLESS OTHERWISE AGREED IN WRITING BY INTEL, THE INTEL PRODUCTS ARE NOT DESIGNED NOR INTENDED FOR ANY APPLICATION IN WHICH THE FAILURE OF THE INTEL PRODUCT COULD CREATE A SITUATION WHERE PERSONAL INJURY OR DEATH MAY OCCUR. Intel may make changes to specifications and product descriptions at any time, without notice. Designers must not rely on the absence or characteristics of any features or instructions marked “reserved” or “undefined.” Intel reserves these for future definition and shall have no responsibility whatsoever for conflicts or incompatibilities arising from future changes to them. The information here is subject to change without notice. Do not finalize a design with this information. The products described in this document may contain design defects or errors known as errata which may cause the product to deviate from published specifications. Current characterized errata are available on request. Contact your local Intel sales office or your distributor to obtain the latest specifications and before placing your product order. -

Adding Support for Vector Instructions to 8051 Architecture

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056 Volume: 05 Issue: 10 | Oct 2018 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072 Adding Support for Vector Instructions to 8051 Architecture Pulkit Gairola1, Akhil Alluri2, Rohan Verma3, Dr. Rajeev Kumar Singh4 1,2,3Student, Dept. of Computer Science, Shiv Nadar University, Uttar, Pradesh, India, 4Assistant Dean & Professor, Dept. of Computer Science, Shiv Nadar University, Uttar, Pradesh, India, ----------------------------------------------------------------------***--------------------------------------------------------------------- Abstract - Majority of the IoT (Internet of Things) devices are Some of the features that have made the 8051 popular are: meant to just collect data and sent it to the cloud for processing. They can be provided with such vectorization • 4 KB on chip program memory. capabilities to carry out very specific computation work and • 128 bytes on chip data memory (RAM) thus reducing latency of output. This project is used to demonstrate how to add specialized 1.2 Components of 8051[2] vectorization capabilities to architectures found in micro- controllers. • 4 register banks. • 128 user defined software flags. The datapath of the 8051 is simple enough to be pliable • 8-bit data bus for adding an experimental Vectorization module. We are • 16-bit address bus trying to make changes to an existing scalar processor so • 16 bit timers (usually 2, but may have more, or less). that it use a single instruction to operate on one- dimensional • 3 internal and 2 external interrupts. arrays of data called vectors. The significant reduction in the • Bit as well as byte addressable RAM area of 16 bytes. Instruction fetch overhead for vectorizable operations is useful • Four 8-bit ports, (short models have two 8-bit ports). -

Datasheet, Volume 2

Intel® Core™ i7-900 Desktop Processor Extreme Edition Series and Intel® Core™ i7-900 Desktop Processor Series on 32-nm Process Datasheet, Volume 2 July 2010 Reference Number: 323253-002 INFORMATION IN THIS DOCUMENT IS PROVIDED IN CONNECTION WITH INTEL® PRODUCTS. NO LICENSE, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, BY ESTOPPEL OR OTHERWISE, TO ANY INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY RIGHTS IS GRANTED BY THIS DOCUMENT. EXCEPT AS PROVIDED IN INTEL'S TERMS AND CONDITIONS OF SALE FOR SUCH PRODUCTS, INTEL ASSUMES NO LIABILITY WHATSOEVER, AND INTEL DISCLAIMS ANY EXPRESS OR IMPLIED WARRANTY, RELATING TO SALE AND/OR USE OF INTEL PRODUCTS INCLUDING LIABILITY OR WARRANTIES RELATING TO FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE, MERCHANTABILITY, OR INFRINGEMENT OF ANY PATENT, COPYRIGHT OR OTHER INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY RIGHT. Intel products are not intended for use in medical, life saving, or life sustaining applications. Intel may make changes to specifications and product descriptions at any time, without notice. Designers must not rely on the absence or characteristics of any features or instructions marked “reserved” or “undefined.” Intel reserves these for future definition and shall have no responsibility whatsoever for conflicts or incompatibilities arising from future changes to them. The Intel® Core™ i7-900 desktop processor Extreme Edition series and Intel® Core™ i7-900 desktop processor series on 32-nm process may contain design defects or errors known as errata which may cause the product to deviate from published specifications. Current characterized errata are available on request. Intel processor numbers are not a measure of performance. Processor numbers differentiate features within each processor family, not across different processor families. See http://www.intel.com/products/processor_number for details. -

MPC500 Family MPC509 User's Manual

MPC509UM/AD MPC500 Family MPC509 User’s Manual Paragraph TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Number Number PREFACE Section 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Features. 1-1 1.2 Block Diagram . 1-2 1.3 Pin Connections. 1-3 1.4 Memory Map . 1-5 Section 2 SIGNAL DESCRIPTIONS 2.1 Pin List . 2-1 2.2 Pin Characteristics . 2-2 2.3 Power Connections . 2-3 2.4 Pins with Internal Pull-Ups and Pulldowns. 2-3 2.5 Signal Descriptions . 2-4 2.5.1 Bus Arbitration and Reservation Support Signals . 2-6 2.5.1.1 Bus Request (BR). 2-6 2.5.1.2 Bus Grant (BG). 2-7 2.5.1.3 Bus Busy (BB) . 2-8 2.5.1.4 Cancel Reservation (CR) . 2-8 2.5.2 Address Phase Signals . 2-8 2.5.2.1 Address Bus (ADDR[0:29]). 2-9 2.5.2.2 Write/Read (WR) . 2-9 2.5.2.3 Burst Indicator (BURST). 2-9 2.5.2.4 Byte Enables (BE[0:3]) . 2-10 2.5.2.5 Transfer Start (TS) . 2-10 2.5.2.6 Address Acknowledge (AACK). 2-10 2.5.2.7 Burst Inhibit (BI) . 2-11 2.5.2.8 Address Retry (ARETRY). 2-12 2.5.2.9 Address Type (AT[0:1]) . 2-12 2.5.2.10 Cycle Types (CT[0:3]). 2-13 2.5.3 Data Phase Signals . 2-13 2.5.3.1 Data Bus (DATA[0:31]). 2-13 2.5.3.2 Burst Data in Progress (BDIP) . -

Introduction to CUDA Programming

Προηγμένη Αρχιτεκτονική Υπολογιστών Non-Uniform Cache Architectures Νεκτάριος Κοζύρης & Διονύσης Πνευματικάτος {nkoziris,pnevmati}@cslab.ece.ntua.gr Διαφάνειες από τον Ανδρέα Μόσχοβο, University of Toronto 8ο εξάμηνο ΣΗΜΜΥ ⎯ Ακαδημαϊκό Έτος: 2019-20 http://www.cslab.ece.ntua.gr/courses/advcomparch/ Modern Processors Have Lots of Cores and Large Caches • Sun Niagara T1 From http://jinsatoh.jp/ennui/archives/2006/03/opensparc.html Modern Processors Have Lots of Cores and Large Caches • Intel i7 (Nehalem) From http://www.legitreviews.com/article/824/1/ Modern Processors Have Lots of Cores and Large Caches • AMD Shanghai From http://www.chiparchitect.com Modern Processors Have Lots of Cores and Large Caches • IBM Power 5 From http://www.theinquirer.net/inquirer/news/1018130/ibms-power5-the-multi-chipped-monster-mcm-revealed Why? • Helps with Performance and Energy • Find graph with perfect vs. realistic memory system What Cache Design Used to be About Core L1I L1D 1-3 cycles / Latency Limited L2 10-16 cycles / Capacity Limited Main Memory > 200 cycles • L2: Worst Latency == Best Latency • Key Decision: What to keep in each cache level What Has Changed ISSCC 2003 What Has Changed • Where something is matters • More time for longer distances NUCA: Non-Uniform Cache Architecture Core L1I L1D • Tiled Cache • Variable Latency L2 L2 L2 L2 • Closer tiles = Faster L2 L2 L2 L2 L2 L2 L2 L2 • Key Decisions: – Not only what to cache L2 L2 L2 L2 – Also where to cache NUCA Overview • Initial Research focused on Uniprocessors • Data Migration Policies – -

Address Decoding Large-Size Binary Decoder: 28-To-268435456 Binary Decoder for 256Mb Memory

Embedded System 2010 SpringSemester Seoul NationalUniversity Application [email protected] Dept. ofEECS/CSE ower Naehyuck Chang P 4190.303C ow- L Introduction to microprocessor interface mbedded aboratory E L L 1 P L E Harvard Architecture Microprocessor Instruction memory Input: address from PC ARM Cortex M3 architecture Output: instruction (read only) Data memory Input: memory address Addressing mode Input/output: read/write data Read or write operand Embedded Low-Power 2 ELPL Laboratory Memory Interface Interface Address bus Data bus Control signals (synchronous and asynchronous) Fully static read operation Input Memory Output Access control Embedded Low-Power 3 ELPL Laboratory Memory Interface Memory device Collection of memory cells: 1M cells, 1G cells, etc. Memory cells preserve stored data Volatile and non-volatile Dynamic and static How access memory? Addressing Input Normally address of the cell (cf. content addressable memory) Memory Random, sequential, page, etc. Output Exclusive cell access One by one (cf. multi-port memory) Operations Read, write, refresh, etc. RD, WR, CS, OE, etc. Access control Embedded Low-Power 4 ELPL Laboratory Memory inside SRAM structure Embedded Low-Power 5 ELPL Laboratory Memory inside Ports Recall D-FF 1 input port and one output port for one cell Ports of memory devices Large number of cells One write port for consistency More than one output ports allow simultaneous accesses of multiple cells for read Register file usually has multiple read ports such as 1W 3R Memory devices usually has one read -

Covert and Side Channels Due to Processor Architecture*

Covert and Side Channels due to Processor Architecture* Zhenghong Wang and Ruby B. Lee Department of Electrical Engineering, Princeton University {zhenghon,rblee}@princeton.edu Abstract analysis [2-5] and timing analysis [6-10]. Different amounts of power (or time) used by the device in Information leakage through covert channels and performing an encryption can be measured and side channels is becoming a serious problem, analyzed to deduce some or all of the key bits. The especially when these are enhanced by modern number of trials needed in a power or timing side processor architecture features. We show how channel attack could be much less than that needed in processor architecture features such as simultaneous mathematical cryptanalysis. multithreading, control speculation and shared caches In this paper, we consider software side channel can inadvertently accelerate such covert channels or attacks. In these attacks, a victim process inadvertently enable new covert channels and side channels. We first assumes the role of the sending process, and a listening illustrate the reality and severity of this problem by (attacker) process assumes the role of the receiving describing concrete attacks. We identify two new process. If the victim process is performing an covert channels. We show orders of magnitude encryption using a secret key, a software side channel increases in covert channel capacities. We then attack allows the listening process to get information present two solutions, Selective Partitioning and the that leads to partial or full recovery of the key. The novel Random Permutation Cache (RPCache). The main contributions of this paper are: RPCache can thwart most cache-based software side • Identification of two new covert channels due to channel attacks, with minimal hardware costs and processor architecture features, like simultaneous negligible performance impact. -

Special Address Generation Arrangement

Patentamt 0 034 1 80 ® êJEuropâischesy))} European Patent Office ® Publication number: Office européen des brevets B1 ® EUROPEAN PATENT SPECIFICATION (§) Dateof publication of patent spécification: 31.10.84 ® Int. Cl.3: G 06 F 9/32 ® Application number: 80901823.7 (22) Date offiling: 11.08.80 (88) International application number: PCT/US80/01017 (87) International publication number: WO 81/00633 05.03.81 Gazette 81/06 @ SPECIAL ADDRESS GENERATION ARRANGEMENT. (§) Priority: 31.08.79 US 71717 (73) Proprietor: Western Electric Company, Incorporated 222 Broadway (43) Date of publication of application: New York, NY 10038 (US) 26.08.81 Bulletin 81/34 (72) Inventor: HUANG, Victor Kuo-Liang (45) Publication of the grant of the patent: 2246 Jersey Avenue 31.10.84 Bulletin 84/44 Scotch Plains, NJ 07090 (US) © Designated Contracting States: (74) Représentative: Weitzel, David Stanley et al DE FR GB NL Western Electric Company Limited 5, Mornington Road Woodford Green Essex IG8 0TU (GB) Références cited: FR-A-1 564 476 US-A-3 297 998 Références cited: US-A-3 343134 IBM TECHNICAL DISCLOSURE BULLETIN, vol. US-A-3 394 350 17, no. 7, december 1974 New York (US) T.G. CÛ US-A-3 533 076 ARTHUR et ai.: "Direct access for text US-A-3 593 313 memory move", pages 1852-1853 o US-A-3 739 345 IBM TECHNICAL DISCLOSURE BULLETIN, vol. US-A-4 00 065 810 19, no. 1,june1976 New York (US) T.J. US-A-4 080 650 DVORAK et al.: "Hardware assist for microcode "An Introduction to IVlicrocomputers Volume I", exécution of storage-to-storage move issued 1976 A. -

Low Overhead Memory Subsystem Design for a Multicore Parallel DSP Processor

Linköping Studies in Science and Technology Dissertation No. 1532 Low Overhead Memory Subsystem Design for a Multicore Parallel DSP Processor Jian Wang Department of Electrical Engineering Linköping University SE-581 83 Linköping, Sweden Linköping 2014 ISBN 978-91-7519-556-8 ISSN 0345-7524 ii Low Overhead Memory Subsystem Design for a Multicore Parallel DSP Processor Jian Wang ISBN 978-91-7519-556-8 Copyright ⃝c Jian Wang, 2014 Linköping Studies in Science and Technology Dissertation No. 1532 ISSN 0345-7524 Department of Electrical Engineering Linköping University SE-581 83 Linköping Sweden Phone: +46 13 28 10 00 Author e-mail: [email protected] Cover image Combined Star and Ring onchip interconnection of the ePUMA multicore DSP. Parts of this thesis are reprinted with permission from the IEEE. Printed by UniTryck, Linköping University Linköping, Sweden, 2014 Abstract The physical scaling following Moore’s law is saturated while the re- quirement on computing keeps growing. The gain from improving sili- con technology is only the shrinking of the silicon area, and the speed- power scaling has almost stopped in the last two years. It calls for new parallel computing architectures and new parallel programming meth- ods. Traditional ASIC (Application Specific Integrated Circuits) hardware has been used for acceleration of Digital Signal Processing (DSP) subsys- tems on SoC (System-on-Chip). Embedded systems become more com- plicated, and more functions, more applications, and more features must be integrated in one ASIC chip to follow up the market requirements. At the same time, the product lifetime of a SoC with ASIC has been much reduced because of the dynamic market. -

The Memory System

The Memory System Fundamental Concepts Some basic concepts Maximum size of the Main Memory byte-addressable CPU-Main Memory Connection Memory Processor k-bit address bus MAR n-bit data bus Up to 2k addressable MDR locations Word length = n bits Control lines ( R / W , MFC, etc.) Some basic concepts(Contd.,) Measures for the speed of a memory: . memory access time. memory cycle time. An important design issue is to provide a computer system with as large and fast a memory as possible, within a given cost target. Several techniques to increase the effective size and speed of the memory: . Cache memory (to increase the effective speed). Virtual memory (to increase the effective size). The Memory System Semiconductor RAM memories Internal organization of memory chips Each memory cell can hold one bit of information. Memory cells are organized in the form of an array. One row is one memory word. All cells of a row are connected to a common line, known as the “word line”. Word line is connected to the address decoder. Sense/write circuits are connected to the data input/output lines of the memory chip. Internal organization of memory chips (Contd.,) 7 7 1 1 0 0 W0 • • • FF FF A 0 W • • 1 • A 1 Address • • • • • • Memory decoder cells A • • • • • • 2 • • • • • • A 3 W • • 15 • Sense / Write Sense / Write Sense / Write R / W circuit circuit circuit CS Data input /output lines: b7 b1 b0 SRAM Cell Two transistor inverters are cross connected to implement a basic flip-flop. The cell is connected to one word line and two bits lines by transistors T1 and T2 When word line is at ground level, the transistors are turned off and the latch retains its state Read operation: In order to read state of SRAM cell, the word line is activated to close switches T1 and T2. -

The CPU and Memory

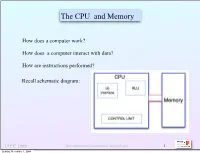

The CPU and Memory How does a computer work? How does a computer interact with data? How are instructions performed? Recall schematic diagram: ITEC 1000 Introduction to Information Technologies 1 Sunday, November 1, 2009 Registers A register is a permanent storage location within the CPU. Registers may contain: • a memory address for communication with memory • an input or output address • data is stored for an arithmetic or logic operation • an instruction in process of execution • codes for special purposes - e.g. keeping track of status • conditions for conditional branch instructions The Little Man Computer had a single register - the accumulator ITEC 1000 Introduction to Information Technologies 2 Sunday, November 1, 2009 Register Characteristics: • directly wired within CPU • not addressed as memory locations for which access time is slow • manipulated by CPU during execution • may be of different sizes depending on function Register names and functions: • program counter register (PC) - holds address of current instruction • instruction register (IR) - holds actual instruction being executed together with parameters • memory address register (MAR) - holds address of a memory location • memory data register (MDR) - holds data being stored or retrieved from memory location addressed by MAR • status registers - indicate such as: arithmetic/logic conditions, memory overflow, power failure, internal error, etc. ITEC 1000 Introduction to Information Technologies 3 Sunday, November 1, 2009 Memory- operation - capacity - implementations -

Intel SGX Explained

Intel SGX Explained Victor Costan and Srinivas Devadas [email protected], [email protected] Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory Massachusetts Institute of Technology ABSTRACT Data Owner’s Remote Computer Computer Intel’s Software Guard Extensions (SGX) is a set of Untrusted Software extensions to the Intel architecture that aims to pro- vide integrity and confidentiality guarantees to security- Computation Container Dispatcher sensitive computation performed on a computer where Setup Computation Setup all the privileged software (kernel, hypervisor, etc) is Private Code Receive potentially malicious. Verification Encrypted This paper analyzes Intel SGX, based on the 3 pa- Results Private Data pers [14, 79, 139] that introduced it, on the Intel Software Developer’s Manual [101] (which supersedes the SGX Owns Manages manuals [95, 99]), on an ISCA 2015 tutorial [103], and Trusts Authors on two patents [110, 138]. We use the papers, reference Trusts manuals, and tutorial as primary data sources, and only draw on the patents to fill in missing information. Data Owner Software Infrastructure This paper does not reflect the information available Provider Owner in two papers [74, 109] that were published after the first Figure 1: Secure remote computation. A user relies on a remote version of this paper. computer, owned by an untrusted party, to perform some computation This paper’s contributions are a summary of the on her data. The user has some assurance of the computation’s Intel-specific architectural and micro-architectural details integrity and confidentiality. needed to understand SGX, a detailed and structured pre- sentation of the publicly available information on SGX, uploads the desired computation and data into the secure a series of intelligent guesses about some important but container.