Natural History of Maguire Primrose, Primula Cusickiana Var. Maguirei (Primulaceae)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary."

Intro 1996 National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands The Fish and Wildlife Service has prepared a National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary (1996 National List). The 1996 National List is a draft revision of the National List of Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1988 National Summary (Reed 1988) (1988 National List). The 1996 National List is provided to encourage additional public review and comments on the draft regional wetland indicator assignments. The 1996 National List reflects a significant amount of new information that has become available since 1988 on the wetland affinity of vascular plants. This new information has resulted from the extensive use of the 1988 National List in the field by individuals involved in wetland and other resource inventories, wetland identification and delineation, and wetland research. Interim Regional Interagency Review Panel (Regional Panel) changes in indicator status as well as additions and deletions to the 1988 National List were documented in Regional supplements. The National List was originally developed as an appendix to the Classification of Wetlands and Deepwater Habitats of the United States (Cowardin et al.1979) to aid in the consistent application of this classification system for wetlands in the field.. The 1996 National List also was developed to aid in determining the presence of hydrophytic vegetation in the Clean Water Act Section 404 wetland regulatory program and in the implementation of the swampbuster provisions of the Food Security Act. While not required by law or regulation, the Fish and Wildlife Service is making the 1996 National List available for review and comment. -

Likely to Have Habitat Within Iras That ALLOW Road

Item 3a - Sensitive Species National Master List By Region and Species Group Not likely to have habitat within IRAs Not likely to have Federal Likely to have habitat that DO NOT ALLOW habitat within IRAs Candidate within IRAs that DO Likely to have habitat road (re)construction that ALLOW road Forest Service Species Under NOT ALLOW road within IRAs that ALLOW but could be (re)construction but Species Scientific Name Common Name Species Group Region ESA (re)construction? road (re)construction? affected? could be affected? Bufo boreas boreas Boreal Western Toad Amphibian 1 No Yes Yes No No Plethodon vandykei idahoensis Coeur D'Alene Salamander Amphibian 1 No Yes Yes No No Rana pipiens Northern Leopard Frog Amphibian 1 No Yes Yes No No Accipiter gentilis Northern Goshawk Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Ammodramus bairdii Baird's Sparrow Bird 1 No No Yes No No Anthus spragueii Sprague's Pipit Bird 1 No No Yes No No Centrocercus urophasianus Sage Grouse Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Cygnus buccinator Trumpeter Swan Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Falco peregrinus anatum American Peregrine Falcon Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Gavia immer Common Loon Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Histrionicus histrionicus Harlequin Duck Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Lanius ludovicianus Loggerhead Shrike Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Oreortyx pictus Mountain Quail Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Otus flammeolus Flammulated Owl Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Picoides albolarvatus White-Headed Woodpecker Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Picoides arcticus Black-Backed Woodpecker Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Speotyto cunicularia Burrowing -

List of Vascular Plants Endemic to Britain, Ireland and the Channel Islands 2020

British & Irish Botany 2(3): 169-189, 2020 List of vascular plants endemic to Britain, Ireland and the Channel Islands 2020 Timothy C.G. Rich Cardiff, U.K. Corresponding author: Tim Rich: [email protected] This pdf constitutes the Version of Record published on 31st August 2020 Abstract A list of 804 plants endemic to Britain, Ireland and the Channel Islands is broken down by country. There are 659 taxa endemic to Britain, 20 to Ireland and three to the Channel Islands. There are 25 endemic sexual species and 26 sexual subspecies, the remainder are mostly critical apomictic taxa. Fifteen endemics (2%) are certainly or probably extinct in the wild. Keywords: England; Northern Ireland; Republic of Ireland; Scotland; Wales. Introduction This note provides a list of vascular plants endemic to Britain, Ireland and the Channel Islands, updating the lists in Rich et al. (1999), Dines (2008), Stroh et al. (2014) and Wyse Jackson et al. (2016). The list includes endemics of subspecific rank or above, but excludes infraspecific taxa of lower rank and hybrids (for the latter, see Stace et al., 2015). There are, of course, different taxonomic views on some of the taxa included. Nomenclature, taxonomic rank and endemic status follows Stace (2019), except for Hieracium (Sell & Murrell, 2006; McCosh & Rich, 2018), Ranunculus auricomus group (A. C. Leslie in Sell & Murrell, 2018), Rubus (Edees & Newton, 1988; Newton & Randall, 2004; Kurtto & Weber, 2009; Kurtto et al. 2010, and recent papers), Taraxacum (Dudman & Richards, 1997; Kirschner & Štepànek, 1998 and recent papers) and Ulmus (Sell & Murrell, 2018). Ulmus is included with some reservations, as many taxa are largely vegetative clones which may occasionally reproduce sexually and hence may not merit species status (cf. -

Condition of Designated Sites

Scottish Natural Heritage Condition of Designated Sites Contents Chapter Page Summary ii Condition of Designated Sites (Progress to March 2010) Site Condition Monitoring 1 Purpose of SCM 1 Sites covered by SCM 1 How is SCM implemented? 2 Assessment of condition 2 Activities and management measures in place 3 Summary results of the first cycle of SCM 3 Action taken following a finding of unfavourable status in the assessment 3 Natural features in Unfavourable condition – Scottish Government Targets 4 The 2010 Condition Target Achievement 4 Amphibians and Reptiles 6 Birds 10 Freshwater Fauna 18 Invertebrates 24 Mammals 30 Non-vascular Plants 36 Vascular Plants 42 Marine Habitats 48 Coastal 54 Machair 60 Fen, Marsh and Swamp 66 Lowland Grassland 72 Lowland Heath 78 Lowland Raised Bog 82 Standing Waters 86 Rivers and Streams 92 Woodlands 96 Upland Bogs 102 Upland Fen, Marsh and Swamp 106 Upland Grassland 112 Upland Heathland 118 Upland Inland Rock 124 Montane Habitats 128 Earth Science 134 www.snh.gov.uk i Scottish Natural Heritage Summary Background Scotland has a rich and important diversity of biological and geological features. Many of these species populations, habitats or earth science features are nationally and/ or internationally important and there is a series of nature conservation designations at national (Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI)), European (Special Area of Conservation (SAC) and Special Protection Area (SPA)) and international (Ramsar) levels which seek to protect the best examples. There are a total of 1881 designated sites in Scotland, although their boundaries sometimes overlap, which host a total of 5437 designated natural features. -

Fall 2013 NARGS

Rock Garden uar terly � Fall 2013 NARGS to ADVERtISE IN thE QuARtERly CoNtACt [email protected] Let me know what yo think A recent issue of a chapter newsletter had an item entitled “News from NARGS”. There were comments on various issues related to the new NARGS website, not all complimentary, and then it turned to the Quarterly online and raised some points about which I would be very pleased to have your views. “The good news is that all the Quarterlies are online and can easily be dowloaded. The older issues are easy to read except for some rather pale type but this may be the result of scanning. There is amazing information in these older issues. The last three years of the Quarterly are also online but you must be a member to read them. These last issues are on Allen Press’s BrightCopy and I find them harder to read than a pdf file. Also the last issue of the Quarterly has 60 extra pages only available online. Personally I find this objectionable as I prefer all my content in a printed bulletin.” This raises two points: Readability of BrightCopy issues versus PDF issues Do you find the BrightCopy issues as good as the PDF issues? Inclusion of extra material in online editions only. Do you object to having extra material in the online edition which can not be included in the printed edition? Please take a moment to email me with your views Malcolm McGregor <[email protected]> CONTRIBUTORS All illustrations are by the authors of articles unless otherwise stated. -

December 2012 Number 1

Calochortiana December 2012 Number 1 December 2012 Number 1 CONTENTS Proceedings of the Fifth South- western Rare and Endangered Plant Conference Calochortiana, a new publication of the Utah Native Plant Society . 3 The Fifth Southwestern Rare and En- dangered Plant Conference, Salt Lake City, Utah, March 2009 . 3 Abstracts of presentations and posters not submitted for the proceedings . 4 Southwestern cienegas: Rare habitats for endangered wetland plants. Robert Sivinski . 17 A new look at ranking plant rarity for conservation purposes, with an em- phasis on the flora of the American Southwest. John R. Spence . 25 The contribution of Cedar Breaks Na- tional Monument to the conservation of vascular plant diversity in Utah. Walter Fertig and Douglas N. Rey- nolds . 35 Studying the seed bank dynamics of rare plants. Susan Meyer . 46 East meets west: Rare desert Alliums in Arizona. John L. Anderson . 56 Calochortus nuttallii (Sego lily), Spatial patterns of endemic plant spe- state flower of Utah. By Kaye cies of the Colorado Plateau. Crystal Thorne. Krause . 63 Continued on page 2 Copyright 2012 Utah Native Plant Society. All Rights Reserved. Utah Native Plant Society Utah Native Plant Society, PO Box 520041, Salt Lake Copyright 2012 Utah Native Plant Society. All Rights City, Utah, 84152-0041. www.unps.org Reserved. Calochortiana is a publication of the Utah Native Plant Society, a 501(c)(3) not-for-profit organi- Editor: Walter Fertig ([email protected]), zation dedicated to conserving and promoting steward- Editorial Committee: Walter Fertig, Mindy Wheeler, ship of our native plants. Leila Shultz, and Susan Meyer CONTENTS, continued Biogeography of rare plants of the Ash Meadows National Wildlife Refuge, Nevada. -

Primulas On-Line

OFFICERS & BOARD American Primrose Society - Summer 2001 1 OF DIRECTORS Primroses EDITOR/GRAPHIC DESIGN Presidents Message Ed Buyarski. President Robert Tonkin P.O. Box 33077 .3155 Pioneer Ave. Juneau, AK 99803-3077 Juneau, AK 99801 Greetings primrose lovers, it's summertime in Alaska! More (907) 789-2299 (907) 463-1554 than enough hours of daylight to weed the garden, plant all AMERICAN PRIMROSt. PKIMUI.A AND AURICULA SOCIETY. INC [email protected] amprimsocC? hotmail.com those hundreds of new seedlings, collect seeds for the APS EDITORIAL COMMITTEE seed exchange, and even work if you have a real job. Sleeping Cheri Fluck. Vice President Robert Tonkin 17275 Point Lena Loop Rd. Judy Sellers this time of year is optional. There'll be lots of dark hours this Juneau, AK 99801 Edward Buyarski fall and winter to catch up on that little item. (907) 789-0595 Primroses l.l)[']'(MilAL DEADLINES After almost no winter, our spring was very cool and our Robert Tonkin. Secretary Winter issue - November 15 season is still nearly three weeks behind normal. My apple trees Quarterly of the 3155 Pioneer Ave. Spring issue - February 15 Summer issue - May 15 are in full bloom on the summer solstice as I write this, so I Juneau, Alaska 99801 hill issue - August 15 American Primrose Society (907)463-1554 may have little green apples for Thanksgiving. Denticulata Volume 59, Number 3, Summer 2001 primroses @>g<;i.net PHOTOGRAPHIC CREDITS primroses were severely damaged by a hard frost in March that Alt photos are credited. brought with it the coldest day of the Winter on the first day of Julia Haldorson. -

National Wetlands Inventory Map Report for Quinault Indian Nation

National Wetlands Inventory Map Report for Quinault Indian Nation Project ID(s): R01Y19P01: Quinault Indian Nation, fiscal year 2019 Project area The project area (Figure 1) is restricted to the Quinault Indian Nation, bounded by Grays Harbor Co. Jefferson Co. and the Olympic National Park. Appendix A: USGS 7.5-minute Quadrangles: Queets, Salmon River West, Salmon River East, Matheny Ridge, Tunnel Island, O’Took Prairie, Thimble Mountain, Lake Quinault West, Lake Quinault East, Taholah, Shale Slough, Macafee Hill, Stevens Creek, Moclips, Carlisle. • < 0. Figure 1. QIN NWI+ 2019 project area (red outline). Source Imagery: Citation: For all quads listed above: See Appendix A Citation Information: Originator: USDA-FSA-APFO Aerial Photography Field Office Publication Date: 2017 Publication place: Salt Lake City, Utah Title: Digital Orthoimagery Series of Washington Geospatial_Data_Presentation_Form: raster digital data Other_Citation_Details: 1-meter and 1-foot, Natural Color and NIR-False Color Collateral Data: . USGS 1:24,000 topographic quadrangles . USGS – NHD – National Hydrography Dataset . USGS Topographic maps, 2013 . QIN LiDAR DEM (3 meter) and synthetic stream layer, 2015 . Previous National Wetlands Inventories for the project area . Soil Surveys, All Hydric Soils: Weyerhaeuser soil survey 1976, NRCS soil survey 2013 . QIN WET tables, field photos, and site descriptions, 2016 to 2019, Janice Martin, and Greg Eide Inventory Method: Wetland identification and interpretation was done “heads-up” using ArcMap versions 10.6.1. US Fish & Wildlife Service (USFWS) National Wetlands Inventory (NWI) mapping contractors in Portland, Oregon completed the original aerial photo interpretation and wetland mapping. Primary authors: Nicholas Jones of SWCA Environmental Consulting. 100% Quality Control (QC) during the NWI mapping was provided by Michael Holscher of SWCA Environmental Consulting. -

(Dr. Sc. Nat.) Vorgelegt Der Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftl

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2012 Flowers, sex, and diversity: Reproductive-ecological and macro-evolutionary aspects of floral variation in the Primrose family, Primulaceae de Vos, Jurriaan Michiel Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-88785 Dissertation Originally published at: de Vos, Jurriaan Michiel. Flowers, sex, and diversity: Reproductive-ecological and macro-evolutionary aspects of floral variation in the Primrose family, Primulaceae. 2012, University of Zurich, Facultyof Science. FLOWERS, SEX, AND DIVERSITY. REPRODUCTIVE-ECOLOGICAL AND MACRO-EVOLUTIONARY ASPECTS OF FLORAL VARIATION IN THE PRIMROSE FAMILY, PRIMULACEAE Dissertation zur Erlangung der naturwissenschaftlichen Doktorwürde (Dr. sc. nat.) vorgelegt der Mathematisch-naturwissenschaftliche Fakultät der Universität Zürich von Jurriaan Michiel de Vos aus den Niederlanden Promotionskomitee Prof. Dr. Elena Conti (Vorsitz) Prof. Dr. Antony B. Wilson Dr. Colin E. Hughes Zürich, 2013 !!"#$"#%! "#$%&$%'! (! )*'+,,&$-+''*$.! /! '0$#1'2'! 3! "4+1%&5!26!!"#"$%&'(#)$*+,-)(*#! 77! "4+1%&5!226!-*#)$%.)(#!'&*#!/'%#+'.0*$)/)"$1'(12%-).'*3'0")"$*.)4&4'*#' "5*&,)(*#%$4'+(5"$.(3(-%)(*#'$%)".'(#'+%$6(#7.'2$(1$*.".! 89! "4+1%&5!2226!.1%&&'%#+',!&48'%'9,%#)()%)(5":'-*12%$%)(5"'"5%&,%)(*#'*3' )0"';."&3(#!'.4#+$*1"<'(#'0")"$*.)4&*,.'%#+'0*1*.)4&*,.'2$(1$*.".! 93! "4+1%&5!2:6!$"2$*+,-)(5"'(12&(-%)(*#.'*3'0"$=*!%14'(#'0*1*.)4&*,.' 2$(1$*.".>'5%$(%)(*#'+,$(#!'%#)0".(.'%#+'$"2$*+,-)(5"'%..,$%#-"'(#' %&2(#"'"#5($*#1"#).! 7;7! "4+1%&5!:6!204&*!"#")(-'%#%&4.(.'*3'!"#$%&''."-)(*#'!"#$%&''$"5"%&.' $%12%#)'#*#/1*#*204&4'%1*#!'1*2$0*&*!(-%&&4'+(.)(#-)'.2"-(".! 773! "4+1%&5!:26!-*#-&,+(#!'$"1%$=.! 7<(! +"=$#>?&@.&,&$%'! 7<9! "*552"*?*,!:2%+&! 7<3! !!"#$$%&'#""!&(! Es ist ein zentrales Ziel in der Evolutionsbiologie, die Muster der Vielfalt und die Prozesse, die sie erzeugen, zu verstehen. -

Rare Plant Survey of San Juan Public Lands, Colorado

Rare Plant Survey of San Juan Public Lands, Colorado 2005 Prepared by Colorado Natural Heritage Program 254 General Services Building Colorado State University Fort Collins CO 80523 Rare Plant Survey of San Juan Public Lands, Colorado 2005 Prepared by Peggy Lyon and Julia Hanson Colorado Natural Heritage Program 254 General Services Building Colorado State University Fort Collins CO 80523 December 2005 Cover: Imperiled (G1 and G2) plants of the San Juan Public Lands, top left to bottom right: Lesquerella pruinosa, Draba graminea, Cryptantha gypsophila, Machaeranthera coloradoensis, Astragalus naturitensis, Physaria pulvinata, Ipomopsis polyantha, Townsendia glabella, Townsendia rothrockii. Executive Summary This survey was a continuation of several years of rare plant survey on San Juan Public Lands. Funding for the project was provided by San Juan National Forest and the San Juan Resource Area of the Bureau of Land Management. Previous rare plant surveys on San Juan Public Lands by CNHP were conducted in conjunction with county wide surveys of La Plata, Archuleta, San Juan and San Miguel counties, with partial funding from Great Outdoors Colorado (GOCO); and in 2004, public lands only in Dolores and Montezuma counties, funded entirely by the San Juan Public Lands. Funding for 2005 was again provided by San Juan Public Lands. The primary emphases for field work in 2005 were: 1. revisit and update information on rare plant occurrences of agency sensitive species in the Colorado Natural Heritage Program (CNHP) database that were last observed prior to 2000, in order to have the most current information available for informing the revision of the Resource Management Plan for the San Juan Public Lands (BLM and San Juan National Forest); 2. -

Annotated Checklist of Vascular Flora, Cedar Breaks National

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Program Center Annotated Checklist of Vascular Flora Cedar Breaks National Monument Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NCPN/NRTR—2009/173 ON THE COVER Peterson’s campion (Silene petersonii), Cedar Breaks National Monument, Utah. Photograph by Walter Fertig. Annotated Checklist of Vascular Flora Cedar Breaks National Monument Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NCPN/NRTR—2009/173 Author Walter Fertig Moenave Botanical Consulting 1117 W. Grand Canyon Dr. Kanab, UT 84741 Editing and Design Alice Wondrak Biel Northern Colorado Plateau Network P.O. Box 848 Moab, UT 84532 February 2009 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Program Center Fort Collins, Colorado The Natural Resource Publication series addresses natural resource topics that are of interest and applicability to a broad readership in the National Park Service and to others in the management of natural resources, including the scientifi c community, the public, and the NPS conservation and environmental constituencies. Manuscripts are peer-reviewed to ensure that the information is scientifi cally credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and is designed and published in a professional manner. The Natural Resource Technical Report series is used to disseminate the peer-reviewed results of scientifi c studies in the physical, biological, and social sciences for both the advancement of science and the achievement of the National Park Service’s mission. The reports provide contributors with a forum for displaying comprehensive data that are often deleted from journals because of page limitations. Current examples of such reports include the results of research that addresses natural resource management issues; natural resource inventory and monitoring activities; resource assessment reports; scientifi c literature reviews; and peer- reviewed proceedings of technical workshops, conferences, or symposia. -

Sensitive Species That Are Not Listed Or Proposed Under the ESA Sorted By: Major Group, Subgroup, NS Sci

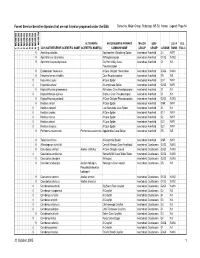

Forest Service Sensitive Species that are not listed or proposed under the ESA Sorted by: Major Group, Subgroup, NS Sci. Name; Legend: Page 94 REGION 10 REGION 1 REGION 2 REGION 3 REGION 4 REGION 5 REGION 6 REGION 8 REGION 9 ALTERNATE NATURESERVE PRIMARY MAJOR SUB- U.S. N U.S. 2005 NATURESERVE SCIENTIFIC NAME SCIENTIFIC NAME(S) COMMON NAME GROUP GROUP G RANK RANK ESA C 9 Anahita punctulata Southeastern Wandering Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G4 NNR 9 Apochthonius indianensis A Pseudoscorpion Invertebrate Arachnid G1G2 N1N2 9 Apochthonius paucispinosus Dry Fork Valley Cave Invertebrate Arachnid G1 N1 Pseudoscorpion 9 Erebomaster flavescens A Cave Obligate Harvestman Invertebrate Arachnid G3G4 N3N4 9 Hesperochernes mirabilis Cave Psuedoscorpion Invertebrate Arachnid G5 N5 8 Hypochilus coylei A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G3? NNR 8 Hypochilus sheari A Lampshade Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G2G3 NNR 9 Kleptochthonius griseomanus An Indiana Cave Pseudoscorpion Invertebrate Arachnid G1 N1 8 Kleptochthonius orpheus Orpheus Cave Pseudoscorpion Invertebrate Arachnid G1 N1 9 Kleptochthonius packardi A Cave Obligate Pseudoscorpion Invertebrate Arachnid G2G3 N2N3 9 Nesticus carteri A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid GNR NNR 8 Nesticus cooperi Lost Nantahala Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G1 N1 8 Nesticus crosbyi A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G1? NNR 8 Nesticus mimus A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G2 NNR 8 Nesticus sheari A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G2? NNR 8 Nesticus silvanus A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G2? NNR