Italoamericana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mafia Motifs in Andrea Camilleri's Detective

MAFIA MOTIFS IN ANDREA CAMILLERI’S DETECTIVE MONTALBANO NOVELS: FROM THE CULTURE AND BREAKDOWN OF OMERTÀ TO MAFIA AS A SCAPEGOAT FOR THE FAILURE OF STATE Adriana Nicole Cerami A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Romance Languages and Literatures (Italian). Chapel Hill 2015 Approved by: Dino S. Cervigni Amy Chambless Roberto Dainotto Federico Luisetti Ennio I. Rao © 2015 Adriana Nicole Cerami ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Adriana Nicole Cerami: Mafia Motifs in Andrea Camilleri’s Detective Montalbano Novels: From the Culture and Breakdown of Omertà to Mafia as a Scapegoat for the Failure of State (Under the direction of Ennio I. Rao) Twenty out of twenty-six of Andrea Camilleri’s detective Montalbano novels feature three motifs related to the mafia. First, although the mafia is not necessarily the main subject of the narratives, mafioso behavior and communication are present in all novels through both mafia and non-mafia-affiliated characters and dialogue. Second, within the narratives there is a distinction between the old and the new generations of the mafia, and a preference for the old mafia ways. Last, the mafia is illustrated as the usual suspect in everyday crime, consequentially diverting attention and accountability away from government authorities. Few critics have focused on Camilleri’s representations of the mafia and their literary significance in mafia and detective fiction. The purpose of the present study is to cast light on these three motifs through a close reading and analysis of the detective Montalbano novels, lending a new twist to the genre of detective fiction. -

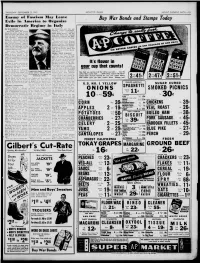

Gilbert S Cut-Rate I

THURSDAY—SEPTEMBER 23, 1943 MONITOR LEADER MOUNT CLEMENS, MICH 13 Ent k inv oh* May L« kav«* Buy War Bonds and Stamps Today Exile in i\meriea to Orijaiiixe w • ll€kiiioi*ralir hi Italy BY KAY HALLE ter Fiammetta. and his son Written for M A Service Sforzino reached Bordeaux, Within 25 year* the United where they m* to board a States has Riven refuge to two Dutch tramp steamer. For five great European Democrats who long days before they reached were far from the end of their Falmouth in England, the Sfor- rope politically. Thomas Mas- zas lived on nothing but orang- aryk. the Czech patriot, after es. a self-imposed exile on spending It war his old friend, Winston shores, return ! after World our Churchill, who finally received to it War I his homrlan after Sforza in London. the The Battle of had been freed from German Britain yoke—as the had commenced. Church- the President of approved to pro- newly-formed Republic—- ill Sforza side i Czech ceed to the United States and after modeled our own. keep the cause of Italian democ- Now, with the collapse of racy aflame. famous exile Italy, another HEADS “FREE ITALIANS” He -* an... JC. -a seems to be 01. the march. J two-year Sforza’-i American . is Count Carlo Sforza, for 20 exile has been spent in New’ years the uncompromising lead- apartment—- opposition York in a modest er of the Democratic that is, he not touring to Italy when is to Fascism. His return the country lecturing and or- imminent seem gazing the affairs of the 300,- Sforza is widely reg rded as in 000 It's flnuor Free Italians in the Western the one Italian who could re- Hemisphere, w hom \e leads construct a democratic form of His New York apartment is government for Italy. -

MOST HOLY REDEEMER CATHOLIC CHURCH Rev

MOST HOLY REDEEMER CATHOLIC CHURCH Rev. Adam Izbicki, Pastor Fr. William Villa, in Residence 8523 Normandy Blvd., Jax., FL 32221-6701 (904) 786-1192 FAX: 786-4224 e-mail: [email protected] Parish Website: www.mhrjax.org Office Hours: M, Tu, Th, F 9:00 am to 1:00 pm Wed. 9:00 am to 4:00 pm MISSION STATEMENT Most Holy Redeemer Parish is a diverse Catholic community of believers who Mass Schedule celebrate and rejoice in the love of God and love of one another. Empowered by the grace of the Holy Spirit, our mission is to invite and welcome all. Masses for the Lord’s Day Saturday Vigil 5:30 pm Sunday 8 am and 10:30 am “I am the good shepherd, and I know mine and mine know me…” Domingo (en español1:00 Jn:10 Weekday Masses Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday and Friday at 8:30 am Viernes (en español) 7:00 pm (No Mass on Mondays except holidays) Reconciliation Saturdays 4:30-5:15 pm or by appointment Exposition of the Blessed Sacrament will follow masses on Fourth Sunday of Easter, April 25, 2021 the first Thursday, Friday and Saturday of each month Parish Staff/ Personnel Mass Intentions Pastor Rev. Adam Izbicki Week of April 25-May 1 904-786-1192 X 226 Requestors [email protected] Rev. William F. Villa Sat Apr 24 530pm +Leonia Laxamana Camacho Fam In residence X 230 [email protected] Sun Apr 25 800am +Casimiro & Lourdes Edido Ching Vianzon Deacon John “Jack” H. Baker Sun Apr 25 1030am +Miller Family Majcak Family 904-477-7252 [email protected] Sun Apr 25 100pm Pro-Populo Deacon Milton Vega Mon Apr 26 No Mass 904-945-8321 [email protected] -

Justice Crucified* a Synopsis, Chronology, and Selective Bibliography of the Sacco and Vanzetti Case

Differentia: Review of Italian Thought Number 8 Combined Issue 8-9 Spring/Autumn Article 21 1999 Remember! Justice Crucified: A Synopsis, Chronology, and Selective Bibliography Gil Fagiani Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.library.stonybrook.edu/differentia Recommended Citation Fagiani, Gil (1999) "Remember! Justice Crucified: A Synopsis, Chronology, and Selective Bibliography," Differentia: Review of Italian Thought: Vol. 8 , Article 21. Available at: https://commons.library.stonybrook.edu/differentia/vol8/iss1/21 This document is brought to you for free and open access by Academic Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Differentia: Review of Italian Thought by an authorized editor of Academic Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Remember! Justice Crucified* A Synopsis, Chronology, and Selective Bibliography of the Sacco and Vanzetti Case Gil Fagiani ____ _ The Enduring Legacy of the Sacco and Vanzetti Case Two Italian immigrants, Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, became celebrated martyrs in the struggle for social justice and politi cal freedom for millions of Italian Americans and progressive-minded people throughout the world. Having fallen into a police trap on May 5, 1920, they eventually were indicted on charges of participating in a payroll robbery in South Braintree, Massachusetts in which a paymas ter and his guard were killed. After an unprecedented international campaign, they were executed in Boston on August 27, 1927. Intense interest in the case stemmed from a belief that Sacco and Vanzetti had not been convicted on the evidence but because they were Italian working-class immigrants who espoused a militant anarchist creed. -

Appendix: Einaudi, President of the Italian Republic (1948–1955) Message After the Oath*

Appendix: Einaudi, President of the Italian Republic (1948–1955) Message after the Oath* At the general assembly of the House of Deputies and the Senate of the Republic, on Wednesday, 12 March 1946, the President of the Republic read the following message: Gentlemen: Right Honourable Senators and Deputies! The oath I have just sworn, whereby I undertake to devote myself, during the years awarded to my office by the Constitution, to the exclusive service of our common homeland, has a meaning that goes beyond the bare words of its solemn form. Before me I have the shining example of the illustrious man who was the first to hold, with great wisdom, full devotion and scrupulous impartiality, the supreme office of head of the nascent Italian Republic. To Enrico De Nicola goes the grateful appreciation of the whole of the people of Italy, the devoted memory of all those who had the good fortune to witness and admire the construction day by day of the edifice of rules and traditions without which no constitution is destined to endure. He who succeeds him made repeated use, prior to 2 June 1946, of his right, springing from the tradition that moulded his sentiment, rooted in ancient local patterns, to an opinion on the choice of the best regime to confer on Italy. But, in accordance with the promise he had made to himself and his electors, he then gave the new republican regime something more than a mere endorsement. The transition that took place on 2 June from the previ- ous to the present institutional form of the state was a source of wonder and marvel, not only by virtue of the peaceful and law-abiding manner in which it came about, but also because it offered the world a demonstration that our country had grown to maturity and was now ready for democracy: and if democracy means anything at all, it is debate, it is struggle, even ardent or * Message read on 12 March 1948 and republished in the Scrittoio del Presidente (1948–1955), Giulio Einaudi (ed.), 1956. -

Ceriani Rowan University Email: [email protected]

Nineteenth-Century Music Review, 14 (2017), pp 211–242. © Cambridge University Press, 2016 doi:10.1017/S1479409816000082 First published online 8 September 2016 Romantic Nostalgia and Wagnerismo During the Age of Verismo: The Case of Alberto Franchetti* Davide Ceriani Rowan University Email: [email protected] The world premiere of Pietro Mascagni’s Cavalleria rusticana on 17 May 1890 immediately became a central event in Italy’s recent operatic history. As contemporary music critic and composer, Francesco D’Arcais, wrote: Maybe for the first time, at least in quite a while, learned people, the audience and the press shared the same opinion on an opera. [Composers] called upon to choose the works to be staged, among those presented for the Sonzogno [opera] competition, immediately picked Mascagni’s Cavalleria rusticana as one of the best; the audience awarded this composer triumphal honours, and the press 1 unanimously praised it to the heavens. D’Arcais acknowledged Mascagni’smeritsbut,inthesamearticle,alsourgedcaution in too enthusiastically festooning the work with critical laurels: the dangers of excessive adulation had already become alarmingly apparent in numerous ill-starred precedents. In the two decades prior to its premiere, several other Italian composers similarly attained outstanding critical and popular success with a single work, but were later unable to emulate their earlier achievements. Among these composers were Filippo Marchetti (Ruy Blas, 1869), Stefano Gobatti (IGoti, 1873), Arrigo Boito (with the revised version of Mefistofele, 1875), Amilcare Ponchielli (La Gioconda, 1876) and Giovanni Bottesini (Ero e Leandro, 1879). Once again, and more than a decade after Bottesini’s one-hit wonder, D’Arcais found himself wondering whether in Mascagni ‘We [Italians] have finally [found] … the legitimate successor to [our] great composers, the person 2 who will perpetuate our musical glory?’ This hoary nationalist interrogative returned in 1890 like an old-fashioned curse. -

Man Is Indestructible: Legend and Legitimacy in the Worlds of Jaroslav Hašek

Man Is Indestructible: Legend and Legitimacy in the Worlds of Jaroslav Hašek The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Weil, Abigail. 2019. Man Is Indestructible: Legend and Legitimacy in the Worlds of Jaroslav Hašek. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:42013078 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA "#$!%&!'$()&*+,-*%./)0!! 1)2)$(!#$(!1)2%*%3#-4!%$!*5)!67+/(&!78!9#+7&/#:!;#<)=! ! ! >!(%&&)+*#*%7$!?+)&)$*)(! ! ! .4!! ! ! >.%2#%/!6)%/! ! ! ! *7! ! ! ! @5)!A)?#+*3)$*!78!B/#:%-!1#$2,#2)&!#$(!1%*)+#*,+)&! ! %$!?#+*%#/!8,/8%//3)$*!78!*5)!+)C,%+)3)$*&! 87+!*5)!()2+))!78! A7-*7+!78!D5%/7&7?54! %$!*5)!&,.E)-*!78! B/#:%-!1#$2,#2)&!#$(!1%*)+#*,+)&! ! ! ! ;#+:#+(!F$%:)+&%*4! ! G#3.+%(2)H!"#&&#-5,&)**&! ! B)?*)3.)+!IJKL! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !!IJKL!M!>.%2#%/!6)%/N! ! >//!+%25*&!+)&)+:)(N ! ! A%&&)+*#*%7$!>(:%&7+0!D+78)&&7+!97$#*5#$!O7/*7$! ! ! ! ! >.%2#%/!6)%/! ! ! "#$!%&!'$()&*+,-*%./)0!1)2)$(!#$(!1)2%*%3#-4!%$!*5)!67+/(&!78!9#+7&/#:!;#<)=! ! !"#$%&'$( ( GP)-5!#,*57+!9#+7&/#:!;#<)=!QKRRSTKLISU!%&!%$*)+$#*%7$#//4!+)$7V$)(!87+!5%&!$7:)/!"#$! %&'$(!)*!'#$!+)),!-).,/$0!12$34!/5!'#$!6)0.,!6&07!A,+%$2!5%&!/%8)*%3)H!()&?%*)!?,./%&5%$2! ?+7/%8%-#//4H!;#<)=!V#&!?+%3#+%/4!=$7V$!#&!#!$7*7+%7,&!?+#$=&*)+N!>$)-(7*)&!2+)V!%$*7!#!/)2)$(! -

Pasquale Stanislao Mancini, Augusto Pierantoni and the International Legal Discourse of 19Th Century Italy

1 Elisabetta FIOCCHI MALASPINA « Toil of the noble world » : Pasquale Stanislao Mancini, Augusto Pierantoni and the international legal discourse of 19th century Italy Abstract : The aim of this article is to reconstruct, from a legal historical point of view, the complexity and the meaning of international law in the Italian peninsula during the 19th century. The paper will analyse different entanglements that constituted the core of nineteenth-century Italian international legal discourse. It is structured in four sections, dealing respectively with : 1) the principle of nationality elaborated by Pasquale Stanislao Mancini and its repercussion both on private and public international law ; 2) the return to the historical origins of Italian international law and the role played by comparative constitutional law ; 3) the implementation and translation of particular legal genres, such as the attempts to codify international law ; 4) colonial education, including legal education, through the creation of the Scuola diplomatico- coloniale (colonial and diplomatic school). Keywords : International law, constitutional law, colonial law, Italy, 19th century Résumé : L’objectif de cet article est de reconstruire, d’un point de vue historico- juridique, la complexité et la signification du droit international dans la péninsule italienne au cours du XIXe siècle. L’article analysera les différents enchevêtrements qui constituaient le cœur du discours juridique international italien du XIXe siècle et il est structuré en quatre sections, traitant respectivement -

Francesco Cherubini

FRANCESCO CHERUBINI. TRE ANNI A MILANO PER CHERUBINI NELLA DIALETTOLOGIA ITALIANA Consonanze 14 Un doppio bicentenario è stato occasione di un’ampia riflessio- ne sulla figura e l’opera di Francesco Cherubini: i duecento anni, nel 2014, del primo Vocabolario milanese-italiano, e gli altrettanti, compiuti due anni dopo, della Collezione delle migliori opere scritte in dialetto milanese. Dai lavori qui raccolti si ridefinisce il profilo di uno studioso, un linguista, non riducibile all’autore di uno stru- FRANCESCO CHERUBINI mento lessicografico su cui s’affaticava spesso con insoddisfazio- ne Manzoni. Il mondo e la cultura della Milano della prima metà dell’Ottocento emergono dalle pagine dei vocabolari cherubiniani TRE ANNI A MILANO PER CHERUBINI e ne emerge anche più nitida la figura dell’autore, non solo ottimo NELLA DIALETTOLOGIA ITALIANA lessicografo ma anche dialettologo tra i più acuti della sua epoca, di un linguista che nessun aspetto degli studi linguistici sembra allontanare da sé. Ma rileggere Cherubini significa anche non sot- ATTI DEI CONVEGNI 2014-2016 trarsi a una riflessione sulla letteratura dialettale: a partire dunque dalla Collezione la terza parte del volume è dedicata ai dialetti d’I- talia come lingue di poesia. A cura di Silvia Morgana e Mario Piotti Silvia Morgana ha insegnato Dialettologia italiana e Storia della lingua italia- na nell’Università degli studi di Milano. Sulla lingua e la cultura milanese e lombarda ha pubblicato molti lavori e un profilo storico complessivo (Storia linguistica di Milano, Roma, Carocci, 2012). Mario Piotti insegna Linguistica italiana e Linguistica dei media all’Università degli Studi di Milano. -

Sacco & Vanzetti

, ' \ ·~ " ~h,S (1'(\$'104 frtn"\i tover) p 0 S t !tV 4 ~ b fa. V\ k ,~ -1 h ~ o '(";,5 I (\ (J. \ • . , SACCO and V ANZETTI ~: LABOR'S MARTYRS t By MAX SHACHTMAN TWENTY-FIVE CENTS f t PubLished by the INTERNATIONAL LABOR DEFENSE NEW YORK 1927 SACCO and VANZETTI LABOR'S MAR TYRS l5jGi~m~""Z"""G':L".~-;,.2=r.~ OWHERE can history find a parallel to m!!-~~m * ~ the case of the two Italian immigrant \<I;j N ~ workers, Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo ~ ~ Vanzetti. Many times before this there ' ~r.il' @~ have been great social upheavals, revolu- i,!:'""";&- J f d I h ~ - ~C{til,}. tlOns, pro oun popu ar movements t at have swept thousands and millions of people into powerful tides of action. But, since the Russian Bolshe vik revolution, where has there yet been a cause that has drawn into its wake the people, not of this or that land, but of all countries, millions from every part and corner of the world; the workers in the metropolis, the peasant on the land, the people of the half-forgotten islands of the sea, men and women and children in all walks of life? There have been other causes that had just as passionate and loyal an adherence, but none with so multitudinous an army. THE PALMER RAIDS If the Sacco-Vanzetti case is regarded as an accidental series of circumstances in which two individuals were unjustly accused of a crime, and then convicted by some inexplicable and unusual flaw in the otherwise pure fabric of justice, it will be quite impossible to understand the first thing about this historic fight. -

Kelt Pub Karaoke Playlista SLO in EX-YU

Kelt pub Karaoke playlista SLO in EX-YU Colonia 1001 noc 25001 Oto Pestner 30 let 25002 Aerodrom Fratello 25066 Agropop Ti si moj soncek 25264 Aleksandar Mezek Siva pot 25228 Alen Vitasovic Gusti su gusti 25072 Alen Vitasovic Jenu noc 25095 Alen Vitasovic Ne moren bez nje 25163 Alfi Nipic Ostal bom muzikant 25187 Alfi Nipic Valcek s teboj 25279 Alka Vuica Lazi me 25118 Alka Vuica Otkad te nema 25190 Alka Vuica Profesionalka 25206 Alka Vuica Varalica 25280 Atomik Harmonik Brizgalna brizga 25021 Atomik Harmonik Hop Marinka 25079 Atomik Harmonik Kdo trka 25109 Azra A sta da radim 25006 Azra Balkan 25017 Azra Fa fa 25064 Azra Gracija 25071 Azra Lijepe zene prolaze kroz grad25123 Azra Pit i to je Amerika 25196 Azra Uzas je moja furka 25278 Bajaga 442 do Beograda 25004 Bajaga Dobro jutro dzezeri 25051 Bajaga Dvadeseti vek 25058 Bajaga Godine prolaze 25070 Bajaga Jos te volim 25097 Bajaga Moji drugovi 25148 Bajaga Montenegro 25149 Bajaga Na vrhovima prstiju 25154 Bajaga Plavi safir 25199 Bajaga Sa druge strane jastuka 25214 Bajaga Tamara 25253 Bajaga Ti se ljubis 25259 Bajaga Tisina 25268 Bajaga Zazmuri 25294 Bebop Ti si moje sonce 25266 Bijelo Dugme A ti me iznevjeri 25007 Bijelo dugme Ako ima Boga 25008 Bijelo dugme Bitanga i princeza 25019 Bijelo dugme Da mi je znati koji joj je vrag25033 Bijelo dugme Da sam pekar 25034 Bijelo Dugme Djurdjevdan 25049 Bijelo dugme Evo zaklet cu se 25063 Bijelo dugme Hajdemo u planine 25077 Bijelo dugme Ima neka tajna veza 25083 Bijelo dugme Jer kad ostari{ 25096 Bijelo dugme Kad zaboravis juli 25106 Bijelo -

Arthur Livingston

Arthur Livingston: An Inventory of His Papers at the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Livingston, Arthur, 1883-1944 Title: Arthur Livingston Papers Inclusive Dates: 1494-1986 Extent: 22 document boxes, 3 galley folders, 1 oversize folder (9.16 linear feet) Access: Open for research Administrative Information Acquisition: Gift, 1950 Processed by: Robert Kendrick, Chip Cheek, Elizabeth Murray, Nov. 1996-June 1997 Repository: Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center The University of Texas at Austin Livingston, Arthur, 1883-1944 Biographical Sketch Arthur Livingston, professor of Romance languages and literatures, publisher, and translator, was born on September 30, 1883, in Northbridge, Massachusetts. Livingston earned the A. B. degree at Amherst College in 1904, continuing his work in Romance languages at Columbia University, where he received the Ph. D. in 1911. His teaching positions included an instructorship in Italian at Smith College (1908-1909), an associate professorship in Italian at Cornell University, where Livingston also supervised the Petrarch Catalogue (1910-1911), and an associate professorship in Romance Languages at Columbia University (1911-1917). Among the various honors bestowed upon Livingston were membership in Phi Beta Kappa and the Venetian academic society, the Reale deputazione veneta di storia patria; he was also decorated as a Cavalier of the Crown of Italy. Livingston's desire to disseminate the work of leading European writers and thinkers in the United States led him to an editorship with the Foreign Press Bureau of the Committee on Public Information during World War I. When the war ended, Livingston, in partnership with Paul Kennaday and Ernest Poole, continued his efforts on behalf of foreign literature by founding the Foreign Press Service, an agency that represented foreign authors in English-language markets.