Perception of the Principal's Role in the State of Israel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conference Schedule and Session Descriptions

2018 Hebrew College Conference for Educators The Multiple Dimensions of Israel CONFERENCE SCHEDULE AND SESSION DESCRIPTIONS http://www.hebrewcollege.edu/2018-EdConference THE CONFERENCE SCHEDULE I. Sunday, October 28 (1:30-4:00pm) – Israel and Hebrew: The Environment as a Teacher Educational visit to the Wonder of Learning Exhibit at Wheelock/Boston University II. Monday, October 29 (9:00-4:00pm) - The Multiple Dimensions of Israel For educators and professionals teaching all ages III. Tuesday, October 30 (8:30am - 3:30pm) - Israel in Early Education For educators and professionals working with children ages 0-8 and their families IV. Tuesday and Wednesday, October 30 and 31 - Best Practices: Learning from the Field Educational site visits - see how Israel and Hebrew can be incorporated into educational settings WORKSHOP SESSIONS AT A GLANCE SUNDAY OCTOBER 28, 2018 Off-site, For All Educators 1:30 to 4:00pm The Wonder of Learning – Israel and Hebrew: The Environment as a Teacher Boston University Wheelock College of Education & Human Development 180 Riverway, Boston, Massachusetts 02215 https://wonderoflearningboston.org MONDAY OCTOBER 29, 2018 For All Educators, on campus of Hebrew College 9:00 to 9:30am Registration, Main Entrance Coffee/Tea, Berenson Hall, Lower Level 9:30 to 10:30am Welcome, Berenson Hall, Lower Level Rachel Raz, Conference Chair “The Multiple Dimensions of Israel and the re-Branding of Israel “ Amir Grinstein, PhD, Associate Professor of Marketing, Northeastern University/VU Amsterdam 2 10:45am to 12:15pm Monday Morning Breakout Sessions - Personal Connections to Israel and Israelis: Lessons from the Boston-Haifa Connection (Marla Olsberg, Panel Facilitator) Berenson Hall, Lower Level - Reimagining Hebrew in our Communities (Tal Gale, Panel Facilitator) Rooms 106-107, Lower Level - Encountering Israel Through Culture (Marion Gribetz) Rooms 102-103, Lower Level - A Very Short Introduction to Zionism and Israel (Rabbi Dr. -

Ben-Gurion University of the Negev the Jacob Blaustein Institutes for Desert Research the Albert Katz International School for Desert Studies

Ben-Gurion University of the Negev The Jacob Blaustein Institutes for Desert Research The Albert Katz International School for Desert Studies Evolution of settlement typologies in rural Israel Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of "Master of Science" By: Keren Shalev November, 2016 “Human settlements are a product of their community. They are the most truthful expression of a community’s structure, its expectations, dreams and achievements. A settlement is but a symbol of the community and the essence of its creation. ”D. Bar Or” ~ III ~ תקציר למשבר הדיור בישראל השלכות מרחיקות לכת הן על המרחב העירוני והן על המרחב הכפרי אשר עובר תהליכי עיור מואצים בעשורים האחרונים. ישובים כפריים כגון קיבוצים ומושבים אשר התבססו בעבר בעיקר על חקלאות, מאבדים מאופיים הכפרי ומייחודם המקורי ומקבלים צביון עירוני יותר. נופי המרחב הכפרי הישראלי נעלמים ומפנים מקום לשכונות הרחבה פרבריות סמי- עירוניות, בעוד זהותה ודמותה הייחודית של ישראל הכפרית משתנה ללא היכר. תופעת העיור המואץ משפיעה לא רק על נופים כפריים, אלא במידה רבה גם על מרחבים עירוניים המפתחים שכונות פרבריות עם בתים צמודי קרקע על מנת להתחרות בכוח המשיכה של ישובים כפריים ולמשוך משפחות צעירות חזקות. כתוצאה מכך, סובלים המרחבים העירוניים, הסמי עירוניים והכפריים מאובדן המבנה והזהות המקוריים שלהם והשוני ביניהם הולך ומיטשטש. על אף שהנושא מעלה לא מעט סוגיות תכנוניות חשובות ונחקר רבות בעולם, מעט מאד מחקר נעשה בנושא בישראל. מחקר מקומי אשר בוחן את תהליכי העיור של המרחב הכפרי דרך ההיסטוריה והתרבות המקומית ולוקח בחשבון את התנאים המקומיים המשתנים, מאפשר התבוננות ואבחנה מדויקים יותר על ההשלכות מרחיקות הלכת. על מנת להתגבר על הבסיס המחקרי הדל בנושא, המחקר הנוכחי החל בבניית בסיס נתונים רחב של 84 ישובים כפריים (קיבוצים, מושבים וישובים קהילתיים( ומצייר תמונה כללית על תהליכי העיור של המרחב הכפרי ומאפייניה. -

The Israel Electric Corporation Ltd. (The "Company")

7.10.2020 The Israel Electric Corporation Ltd. (the "Company") Updated list of the Company's Shareholders 1. Following is an updated list of the Company's Shareholders: Shareholders – Israel # Name of Shareholder Address I.D . # Ordinary Shares of NIS 0.10 each 1 Aminoff Perjulah and Latfula 4 Havazelet street, Jerusalem 1,650 by Akajan Palti 94224 2 Barlev Yehuda 3aTolkovski street, Tel Aviv 69358 64837123 95 3 Birkenheim Alwxander Unknown address 8 4 Braker Yair 14 Rachel street, Haifa 34401 226583 8 5 Goldstein Ben-Zion 20/20 Modi`in street, Kiriat Ono 713800 112 5502208 6 Goldstein Nir 8 Peretz st, Givat Shmuel 1 7 Goldstein Zvi Ran 22 b Shvarech street, Ra'anana 024323644 1 8 Gorodish Baruch P.O.B 29, Sha'arei Tikva 1 Efraim 44810 9 Dvir Yosef 8 Giborei Gehtto Varsha street, 1 Haifa 10 Davidzon - Gotter Sarah 621 Ahuzat Poleg, 45805 Kibbutz 1 Tel Yitzhak 11 Dekel Giorah 4 Haikar street, Pardes Hanah – 15 Karkur, 3709604 12 Hessel Yoram 17 Nisim Aloni St. Tel Aviv 06800908 1 6291938 13 Hershter Yakov Itzhak 10 Ruppin street, Tel Aviv 6357612 57743759 572 14 Efrat Zeibert 11 Borohov St., Givataim 4,006 15 Zelinger Dov 2 Ori street, Tel Aviv 2180719 95 16 Ophir Naor, Adv. Ltd. 6 Wissotzky, Tel Aviv 6233801 Company number 26 513937094 17 Renan Gresht, Adv. Ltd. 6 Wissotzky, Tel Aviv 6233801 Company number 26 514140987 18 Hazan Dov 4a Narkis street, Kiryat Yam A, 95 2950106 19 Nissim Hilu 7 Beilis St., Haifa 3481407 005868237 1 20 David Yahav 7/30 Nachal Alexander st., Tzur 50258946 1 Itzhak 21 Eitzhak (Ika) Yakin 17 Levona St. -

From Deficits and Dependence to Balanced Budgets and Independence

From Deficits and Dependence to Balanced Budgets and Independence The Arab Local Authorities’ Revenue Sources Michal Belikoff and Safa Agbaria Edited by Shirley Racah Jerusalem – Haifa – Nazareth April 2014 From Deficits and Dependence to Balanced Budgets and Independence The Arab Local Authorities’ Revenue Sources Michal Belikoff and Safa Agbaria Edited by Shirley Racah Jerusalem – Haifa – Nazareth April 2014 From Deficits and Dependence to Balanced Budgets and Independence The Arab Local Authorities’ Revenue Sources Research and writing: Michal Belikoff and Safa Ali Agbaria Editing: Shirley Racah Steering committee: Samah Elkhatib-Ayoub, Ron Gerlitz, Azar Dakwar, Mohammed Khaliliye, Abed Kanaaneh, Jabir Asaqla, Ghaida Rinawie Zoabi, and Shirley Racah Critical review and assistance with research and writing: Ron Gerlitz and Shirley Racah Academic advisor: Dr. Nahum Ben-Elia Co-directors of Sikkuy’s Equality Policy Department: Abed Kanaaneh and Shirley Racah Project director for Injaz: Mohammed Khaliliye Hebrew language editing: Naomi Glick-Ozrad Production: Michal Belikoff English: IBRT Jerusalem Graphic design: Michal Schreiber Printed by: Defus Tira This pamphlet has also been published in Arabic and Hebrew and is available online at www.sikkuy.org.il and http://injaz.org.il Published with the generous assistance of: The European Union This publication has been produced with the assistance of the European Union. Its contents are the sole responsibility of Sikkuy and Injaz and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union. The Moriah Fund UJA-Federation of New York The Jewish Federations of North America Social Venture Fund for Jewish-Arab Equality and Shared Society The Alan B. -

Jewish Behavior During the Holocaust

VICTIMS’ POLITICS: JEWISH BEHAVIOR DURING THE HOLOCAUST by Evgeny Finkel A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Political Science) at the UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN–MADISON 2012 Date of final oral examination: 07/12/12 The dissertation is approved by the following members of the Final Oral Committee: Yoshiko M. Herrera, Associate Professor, Political Science Scott G. Gehlbach, Professor, Political Science Andrew Kydd, Associate Professor, Political Science Nadav G. Shelef, Assistant Professor, Political Science Scott Straus, Professor, International Studies © Copyright by Evgeny Finkel 2012 All Rights Reserved i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation could not have been written without the encouragement, support and help of many people to whom I am grateful and feel intellectually, personally, and emotionally indebted. Throughout the whole period of my graduate studies Yoshiko Herrera has been the advisor most comparativists can only dream of. Her endless enthusiasm for this project, razor- sharp comments, constant encouragement to think broadly, theoretically, and not to fear uncharted grounds were exactly what I needed. Nadav Shelef has been extremely generous with his time, support, advice, and encouragement since my first day in graduate school. I always knew that a couple of hours after I sent him a chapter, there would be a detailed, careful, thoughtful, constructive, and critical (when needed) reaction to it waiting in my inbox. This awareness has made the process of writing a dissertation much less frustrating then it could have been. In the future, if I am able to do for my students even a half of what Nadav has done for me, I will consider myself an excellent teacher and mentor. -

The National Left (First Draft) by Shmuel Hasfari and Eldad Yaniv

The National Left (First Draft) by Shmu'el Hasfari and Eldad Yaniv Open Source Center OSC Summary: A self-published book by Israeli playwright Shmu'el Hasfari and political activist Eldad Yaniv entitled "The National Left (First Draft)" bemoans the death of Israel's political left. http://www.fas.org/irp/dni/osc/israel-left.pdf Statement by the Authors The contents of this publication are the responsibility of the authors, who also personally bore the modest printing costs. Any part of the material in this book may be photocopied and recorded. It is recommended that it should be kept in a data-storage system, transmitted, or recorded in any form or by any electronic, optical, mechanical means, or otherwise. Any form of commercial use of the material in this book is permitted without the explicit written permission of the authors. 1. The Left The Left died the day the Six-Day War ended. With the dawn of the Israeli empire, the Left's sun sank and the Small [pun on Smol, the Hebrew word for Left] was born. The Small is a mark of Cain, a disparaging term for a collaborator, a lover of Arabs, a hater of Israel, a Jew who turns against his own people, not a patriot. The Small-ists eat pork on Yom Kippur, gobble shrimps during the week, drink espresso whenever possible, and are homos, kapos, artsy-fartsy snobs, and what not. Until 1967, the Left actually managed some impressive deeds -- it took control of the land, ploughed, sowed, harvested, founded the state, built the army, built its industry from scratch, fought Arabs, settled the land, built the nuclear reactor, brought millions of Jews here and absorbed them, and set up kibbutzim, moshavim, and agriculture. -

Return of Organization Exempt from Income

Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax Form 990 Under section 501 (c), 527, or 4947( a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code (except black lung benefit trust or private foundation) 2005 Department of the Treasury Internal Revenue Service ► The o rganization may have to use a copy of this return to satisfy state re porting requirements. A For the 2005 calendar year , or tax year be and B Check If C Name of organization D Employer Identification number applicable Please use IRS change ta Qachange RICA IS RAEL CULTURAL FOUNDATION 13-1664048 E; a11gne ^ci See Number and street (or P 0. box if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite E Telephone number 0jretum specific 1 EAST 42ND STREET 1400 212-557-1600 Instruo retum uons City or town , state or country, and ZIP + 4 F nocounwro memos 0 Cash [X ,camel ded On° EW YORK , NY 10017 (sped ► [l^PP°ca"on pending • Section 501 (Il)c 3 organizations and 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trusts H and I are not applicable to section 527 organizations. must attach a completed Schedule A ( Form 990 or 990-EZ). H(a) Is this a group return for affiliates ? Yes OX No G Website : : / /AICF . WEBNET . ORG/ H(b) If 'Yes ,* enter number of affiliates' N/A J Organization type (deckonIyone) ► [ 501(c) ( 3 ) I (insert no ) ] 4947(a)(1) or L] 527 H(c) Are all affiliates included ? N/A Yes E__1 No Is(ITthis , attach a list) K Check here Q the organization' s gross receipts are normally not The 110- if more than $25 ,000 . -

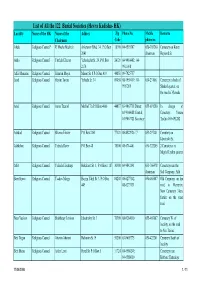

List of All the 122 Burial Societies (Hevra Kadisha- HK) Locality Name of the HK Name of the Addres Zip Phone No

List of All the 122 Burial Societies (Hevra Kadisha- HK) Locality Name of the HK Name of the Addres Zip Phone No. Mobile Remarks Chairman Code phone no. Afula Religious Council* R' Moshe Mashiah Arlozorov Blvd. 34, P.O.Box 18100 04-6593507 050-303260 Cemetery on Keren 2041 chairman Hayesod St. Akko Religious Council Yitzhak Elharar Yehoshafat St. 29, P.O.Box 24121 04-9910402; 04- 2174 9911098 Alfei Menashe Religious Council Shim'on Moyal Manor St. 8 P.O.Box 419 44851 09-7925757 Arad Religious Council Hayim Tovim Yehuda St. 34 89058 08-9959419; 08- 050-231061 Cemetery in back of 9957269 Shaked quarter, on the road to Massada Ariel Religious Council Amos Tzuriel Mish'ol 7/a P.O.Box 4066 44837 03-9067718 Direct; 055-691280 In charge of 03-9366088 Central; Cemetery: Yoram 03-9067721 Secretary Tzefira 055-691282 Ashdod Religious Council Shlomo Eliezer P.O.Box 2161 77121 08-8522926 / 7 053-297401 Cemetery on Jabotinski St. Ashkelon Religious Council Yehuda Raviv P.O.Box 48 78100 08-6714401 050-322205 2 Cemeteries in Migdal Tzafon quarter Atlit Religious Council Yehuda Elmakays Hakalanit St. 1, P.O.Box 1187 30300 04-9842141 053-766478 Cemetery near the chairman Salt Company, Atlit Beer Sheva Religious Council Yaakov Margy Hayim Yahil St. 3, P.O.Box 84208 08-6277142, 050-465887 Old Cemetery on the 449 08-6273131 road to Harzerim; New Cemetery 3 km. further on the same road Beer Yaakov Religious Council Shabbetay Levison Jabotinsky St. 3 70300 08-9284010 055-465887 Cemetery W. -

The Philistines Are Upon You, Samson

23:35 , 07.31.07 Print The Philistines are upon you, Samson Samson was known for his great strength and bravery, but the places in Bible which, according to tradition, he lived and acted are not as well known. Eyal Davidson visits the home grounds of this heroic figure: from his grave in Tel Tzora to the altar of his father, Manoach, where his barren mother received word of her pregnancy Eyal Davidson Samson lived a very stormy life. It began with his miraculous birth and continued with Israel’s wars with the Philistines, which revolved around the romances that he conducted with Philistine women. Its end was a dramatic event that concluded with his bringing down the Philistine temple on top of its inhabitants. Samson lived during the era of the Judges, when the twelve tribes of Israel were attempting to become established in the portions that they received from Joshua Bin-Nun. Samson’s family was from Tzora, a city on the border of the portion of the tribes of Judah and Dan, and that is Samson slaughtering where he began to reveal his legendary strength. the lion Samson died in Gaza, when he brought In the footsteps of kings click here to down the Philistine temple on its enlarge text inhabitants and on himself. “And Samson Following King David in the said, “Let me die with the Philistines”…and they buried him between Judean lowlands / Gadi Vexler Tzora and Eshtaol in the burying place of Almost everywhere in Israel is mentioned Manoach his father” (Judges 15: 30-31). -

Israeli Settler-Colonialism and Apartheid Over Palestine

Metula Majdal Shams Abil al-Qamh ! Neve Ativ Misgav Am Yuval Nimrod ! Al-Sanbariyya Kfar Gil'adi ZZ Ma'ayan Baruch ! MM Ein Qiniyye ! Dan Sanir Israeli Settler-Colonialism and Apartheid over Palestine Al-Sanbariyya DD Al-Manshiyya ! Dafna ! Mas'ada ! Al-Khisas Khan Al-Duwayr ¥ Huneen Al-Zuq Al-tahtani ! ! ! HaGoshrim Al Mansoura Margaliot Kiryat !Shmona al-Madahel G GLazGzaGza!G G G ! Al Khalsa Buq'ata Ethnic Cleansing and Population Transfer (1948 – present) G GBeGit GHil!GlelG Gal-'A!bisiyya Menara G G G G G G G Odem Qaytiyya Kfar Szold In order to establish exclusive Jewish-Israeli control, Israel has carried out a policy of population transfer. By fostering Jewish G G G!G SG dGe NG ehemia G AGl-NGa'iGmaG G G immigration and settlements, and forcibly displacing indigenous Palestinians, Israel has changed the demographic composition of the ¥ G G G G G G G !Al-Dawwara El-Rom G G G G G GAmG ir country. Today, 70% of Palestinians are refugees and internally displaced persons and approximately one half of the people are in exile G G GKfGar GB!lGumG G G G G G G SGalihiya abroad. None of them are allowed to return. L e b a n o n Shamir U N D ii s e n g a g e m e n tt O b s e rr v a tt ii o n F o rr c e s Al Buwayziyya! NeoG t MG oGrdGecGhaGi G ! G G G!G G G G Al-Hamra G GAl-GZawG iyGa G G ! Khiyam Al Walid Forcible transfer of Palestinians continues until today, mainly in the Southern District (Beersheba Region), the historical, coastal G G G G GAl-GMuGftskhara ! G G G G G G G Lehavot HaBashan Palestinian towns ("mixed towns") and in the occupied West Bank, in particular in the Israeli-prolaimed “greater Jerusalem”, the Jordan G G G G G G G Merom Golan Yiftah G G G G G G G Valley and the southern Hebron District. -

France's Jewish Community Threatened

30 INSIDE www.jewishnewsva.org Southeastern Virginia | Vol. 53 No. 10 | 5 Shevet 5775 | January 26, 2015 France’s 12 Community hears Ira Forman on Jewish community anti-Semitism threatened —page 6 28 Dana Cohen Day at Indian Lakes High School 31 A Hebrew Academy of Tidewater story SILENCE WON’T REPAIR THE WORLD 3 Mazel Mazel MazelTov Tov MazelTov Tov 5000 Corporate Woods Drive, Suite 200 Non-Profit Org. MAZELMAZEL Virginia Beach, Virginia 23462-4370 US POSTAGE MazelTov Address Service Requested PAID MAZELMAZEL TOVTOVTOVMazelTov Suburban MD MAZEL Permit 6543 MazelMazel TovTov TOV 32 MazelMazel TovMAZEL Date with the State MazelMazel TOV Wednesday, Feb. 4 Supplement to Jewish News January 26, 2015 M azel Tov Supplement to Jewish News January 26, 2015 MTovTov azel Tov MM a z e l To v jewishnewsva.org | January 26, 2015 | JEWISH NEWS | 1 Redi Carpet - VAB - 12.5.14.pdf 1 12/5/2014 4:53:43 PM MakeMake youryour househouse aa homehome Come by and visit one of our expert flooring consultants and view thousands of samples of Carpet, Hardwood, Ceramic Tile and more! C M I was very pleased to have new Y CM “ carpet all in one day. It looks MY CY great. Wish I had done it sooner! CMY K I will definitely recommend Redi Carpet to others. -K. Rigney, Home Owner ” (757) 481-9646 2220 West Great Neck Road | Virginia Beach, VA 23451 2 | JEWISH NEWS | January 26, 2015 | jewishnewsva.org www.redicarpet.com UPFRONT JEWisH neWS jewishnewsva.org Published 22 times a year by United Jewish Federation “Our lives begin to end the day we of Tidewater. -

Messianic Yisra'el Daily & Shabbat Siddur

BEIT IMMANUEL Global Outreach Synagogue YHVH PUBLISHING HOUSE Holy to ADONAI MESSIANIC YISR A'EL SIDDUR DAILY & SHABBAT SIDDUR PRAYER BOOK BEIT IMMANUEL Global Outreach Synagogue by YHVH PUBLISHING HOUSE Messianic Yisra'el Daily & Shabbat Siddur THE GIFT AND BEAUTY OF SHABBAT When ADONAI rested from His work of creation, He gave us the 7th Day - the Shabbat (or Shabbat). ADONAI sanctified this day and taught us to do likewise. So the Shabbat is given as a sign between ADONAI and His people, and as a commemoration of our Creator, and the very act of creation. In its simplest definition, "Shabbat" means "Rest," and so each Shabbat is a day of rest ... rest in the sense of ceasing from all the normal work & activities of the other six days of the week. It is to be a time of joy, peace and tranquility, away from the cares and worries of the world. ADONAI Elohim calls each Shabbat day "a holy convocation". "Convocation" means a "gathering together"; it is a group of believers assembling or gathering for worship, praise, and celebration. Shabbat is a day of rejoicing and joining with one another in the Presence of ADONAI! The Shabbat is a picture of the Olam Ha'Ba, or the world to come. In the rhythm of the Olam Ha'Zeh, or the present world that we live in now, however, the Shabbat is a sacred time to become spiritually reconnected with our true identities, as ADONAI Elohim's own children. "I have a precious gift in my treasure house, said ADONAI Elohim to Moses,'Shabbat' is its name; go and tell Yisra'el I wish to present it to them." ( Genesis 2:2 ) The children of Yisra'el shall keep the Shabbat throughout their generations as a covenant forever.