Getting on Track – High Speed Railways in Japan and the UK

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bullets and Trains: Exporting Japan's Shinkansen to China and Taiwan

Volume 5 | Issue 3 | Article ID 2367 | Mar 01, 2007 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus Bullets and Trains: Exporting Japan's Shinkansen to China and Taiwan Christopher P. Hood Bullets and Trains: ExportingJapan ’s Japan, like many other countries has a de facto Shinkansen to China and Taiwan two-China policy with formal recognition of the People’s Republic but extensive economic and By Christopher P. Hood other ties with the Republic. One example of this dual policy is the use of Haneda Airport by China Airlines (Taiwan), but the use of Narita It is over forty years since the Shinkansen Airport by airlines from China. (‘bullet train’) began operating between Tokyo and Osaka. Since then the network has The Shinkansen expanded, but other countries, most notably France and Germany, have been developing The Shinkansen is one ofJapan ’s iconic their own high speed railways, too. As other symbols. The image ofMount Fuji with a countries, mainly in Asia, look to develop high passing Shinkansen is one of the most speed railways, the battle over which country projected images of Japan. The history of the will win the lucrative contracts for them is on. Shinkansen dates back to the Pacific War. It is not only a matter of railway technology. Shima Yasujiro’s plan for thedangan ressha Political, economic & cultural influences are (‘bullet train’) then included the idea of a line also at stake. This paper will look at these linking Tokyo with Korea and China (1). various aspects in relation to the export of the Although that plan never materialised, the Shinkansen to China in light of previous Shinkansen idea was reborn nearly two Japanese attempts to export the Shinkansen decades later, as yume-no-chotokkyu (‘super and the situation in Taiwan. -

Case of High-Speed Ground Transportation Systems

MANAGING PROJECTS WITH STRONG TECHNOLOGICAL RUPTURE Case of High-Speed Ground Transportation Systems THESIS N° 2568 (2002) PRESENTED AT THE CIVIL ENGINEERING DEPARTMENT SWISS FEDERAL INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY - LAUSANNE BY GUILLAUME DE TILIÈRE Civil Engineer, EPFL French nationality Approved by the proposition of the jury: Prof. F.L. Perret, thesis director Prof. M. Hirt, jury director Prof. D. Foray Prof. J.Ph. Deschamps Prof. M. Finger Prof. M. Bassand Lausanne, EPFL 2002 MANAGING PROJECTS WITH STRONG TECHNOLOGICAL RUPTURE Case of High-Speed Ground Transportation Systems THÈSE N° 2568 (2002) PRÉSENTÉE AU DÉPARTEMENT DE GÉNIE CIVIL ÉCOLE POLYTECHNIQUE FÉDÉRALE DE LAUSANNE PAR GUILLAUME DE TILIÈRE Ingénieur Génie-Civil diplômé EPFL de nationalité française acceptée sur proposition du jury : Prof. F.L. Perret, directeur de thèse Prof. M. Hirt, rapporteur Prof. D. Foray, corapporteur Prof. J.Ph. Deschamps, corapporteur Prof. M. Finger, corapporteur Prof. M. Bassand, corapporteur Document approuvé lors de l’examen oral le 19.04.2002 Abstract 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to extend my deep gratitude to Prof. Francis-Luc Perret, my Supervisory Committee Chairman, as well as to Prof. Dominique Foray for their enthusiasm, encouragements and guidance. I also express my gratitude to the members of my Committee, Prof. Jean-Philippe Deschamps, Prof. Mathias Finger, Prof. Michel Bassand and Prof. Manfred Hirt for their comments and remarks. They have contributed to making this multidisciplinary approach more pertinent. I would also like to extend my gratitude to our Research Institute, the LEM, the support of which has been very helpful. Concerning the exchange program at ITS -Berkeley (2000-2001), I would like to acknowledge the support of the Swiss National Science Foundation. -

The Railway Museum As Science, Industry and History Museum —Past, Present, and Future— Ichiro Tsutsumi

World Railway Museums (part 2) The Railway Museum as Science, Industry and History Museum —Past, Present, and Future— Ichiro Tsutsumi Introduction Great Kanto Earthquake, but reopened in 1925 in the same location with more collections. This article presents a short history of railway museums in A new reinforced-concrete building was constructed Japan, their current state, and perceptions on their future as on the site of the former Manseibashi Station on the Chuo industrial technology history museums. Line in 1936 to be used as the new Railway Museum, and the collections were transferred there. The museum was Brief History of Railway Museums in Japan renamed the Transportation Museum after World War II, and was administered and operated by the Transportation Culture The first systematic efforts to preserve railway-related Promotion Foundation. It became a general transportation materials (documents and artefacts) for posterity in Japan museum handling materials related to ships, aircraft, and were made by the Railway Agency (1908–20). The project automobiles in addition to railways, and was visited by many was started by Shimpei Goto (1857–1929), the first president people. The Transportation Museum closed in that location of the Railway Agency, who established the Railway in 2006 for relocation to Saitama City in Saitama Prefecture. Museum Trust in 1911. The following year, the trust took It reopened as The Railway Museum of East Japan Railway custody of the first and second Imperial carriages, along Culture Foundation (EJRCF) in 2007. The same foundation with 121 other items (called reference items at the time) also administers and operates Ome Railway Park in including an Imperial funeral carriage to be archived in a suburban Tokyo. -

The Tohoku Traveler Was Created As a Public Service for the Members of the Misawa Community

TOHOKUTOHOKU TRAVELERTRAVELER “.....each day is a journey, and the journey itself home” Basho 1997 TOHOKU TRAVELER STAFF It is important to first acknowledge the members of the Yokota Officers’ Spouses’ Club and anyone else associated with the publication of their original “Travelogue.” Considerable information in Misawa Air Base’s “Tohoku Traveler” is based on that publication. Some of these individuals are: P.W. Edwards Pat Nolan Teresa Negley V.L. Paulson-Cody Diana Hall Edie Leavengood D. Lyell Cheryl Raggia Leda Marshall Melody Hostetler Vicki Collins However, an even amount of credit must also be given to the many volunteers and Misawa Air Base Family Support Flight staff members. Their numerous articles and assistance were instrumental in creating Misawa Air Base’s regionally unique “Tohoku Traveler.” They are: EDITING/COORDINATING STAFF Tohoku Traveler Coordinator Mark Johnson Editors Debra Haas, Dottie Trevelyan, Julie Johnson Layout Staff Laurel Vincent, Sandi Snyder, Mark Johnson Photo Manager/Support Mark Johnson, Cherie Thurlby, Keith Dodson, Amber Jordon Technical Support Brian Orban, Donna Sellers Cover Art Wendy White Computer Specialist Laurel Vincent, Kristen Howell Publisher Family Support Flight, Misawa Air Base, APO AP 96319 Printer U.S. Army Printing and Publication Center, Korea WRITERS Becky Stamper Helen Sudbecks Laurel Vincent Marion Speranzo Debra Haas Lisa Anderson Jennifer Boritski Dottie Trevelyan Corren Van Dyke Julie Johnson Sandra Snyder Mark Johnson Anne Bowers Deborah Wajdowicz Karen Boerman Satoko Duncan James Gibbons Jody Rhone Stacy Hillsgrove Yuriko Thiem Wanda Giles Tom Zabel Hiraku Maita Larry Fuller Joe Johnson Special Note: The Misawa Family Support Flight would like to thank the 35 th Services Squadron’s Travel Time office for allowing the use of material in its “Tohoku Guide” while creating this publication. -

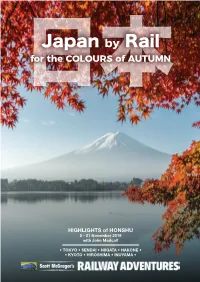

Japan by Rail for the COLOURS of AUTUMN

Japan by Rail for the COLOURS of AUTUMN HIGHLIGHTS of HONSHU 5 - 21 November 2019 with John Medcalf • TOKYO • SENDAI • NIIGATA • HAKONE • • KYOTO • HIROSHIMA • INUYAMA • OVERVIEW It’s not hard to argue the merits of train travel, but to truly HIGHLIGHTS discover how far rail technology has come in the last two centuries you simply have to visit Japan. Its excellent • Extensive rail travel using your JR Green Class (first class) Rail railway system is one of the world’s most extensive and Pass, including several journeys on the iconic bullet trains advanced, and train travel is unarguably the best way • Travel by steam train on the famous heritage railways of to explore this fascinating country. Speed, efficiency, Yamaguchi and the Banetsu lines comfort, convenience and a choice of spectacular destinations are hallmarks of travel by train in Japan. • Ride the Sagano Forest Railway, Tozan Mountain Railway, regional expresses, subways and a vintage tram charter in Tour summary Hiroshima • Cruise around the Matsushima Islands and Hiroshima Bay Join John Medcalf and discover the highlights of Japan’s main island Honshu on this exciting journey. to Miyajima It begins in the modern neon-lit capital of Tokyo, • Pay homage at Hiroshima Peace Park and visit the newly where the famous bullet train will take you north-west renovated museum to Niigata followed by a special steam train across • Explore historic temples, castles and cultural sites in Tokyo, the heart of Honshu. You’ll travel through mountains, Kyoto and Himeji valleys and forests full of deciduous trees ablaze with • Visit the unsurpassed modern railway museums in Tokyo autumn colours to Sendai where the story of Japan’s and Kyoto coast unfolds while exploring the Matsushima Islands. -

Jclettersno Heading

.HERITAGE RAILWAY ASSOCIATION. Mark Garnier MP (2nd left) presents the HRA Annual Award (Large Groups) to members of the Isle of Wight Steam Railway and the Severn Valley Railway, joint winners of the award. (Photo. Gwynn Jones) SIDELINES 143 FEBRUARY 2016 WOLVERHAMPTON LOW LEVEL STATION COMES BACK TO LIFE FOR HRA AWARDS NIGHT. The Grand Station banqueting centre, once the GWR’s most northerly broad gauge station, came back to life as a busy passenger station when it hosted the Heritage Railway Association 2015 Awards Night. The HRA Awards recognise a wide range of achievements and distinctions across the entire heritage railway industry, and the awards acknowledge individuals and institutions as well as railways. The February 6th event saw the presentation of awards in eight categories. The National Railway Museum and York Theatre Royal won the Morton’s Media (Heritage Railways) Interpretation Award, for an innovative collaboration that joined theatre with live heritage steam, when the Museum acted as a temporary home for the theatre company. The Railway Magazine Annual Award for Services to Railway Preservation was won by David Woodhouse, MBE, in recognition of his remarkable 60-year heritage railways career, which began as a volunteer on the Talyllyn Railway, and took him to senior roles across the heritage railways and tourism industry. The North Yorkshire Moors Railway won the Morton’s Media (Rail Express) Modern Traction Award, for their diesel locomotive operation, which included 160 days working for their Crompton Class 25. There were two winners of the Steam Railway Magazine Award. The Great Little Trains of North Wales was the name used by the judges to describe the Bala Lake Railway, Corris Railway, Ffestiniog & Welsh Highland Railway, Talyllyn Railway, Vale of Rheidol Railway and the Welshpool & Llanfair Railway. -

Shinkansen - Wikipedia 7/3/20, 10�48 AM

Shinkansen - Wikipedia 7/3/20, 10)48 AM Shinkansen The Shinkansen (Japanese: 新幹線, pronounced [ɕiŋkaꜜɰ̃ seɴ], lit. ''new trunk line''), colloquially known in English as the bullet train, is a network of high-speed railway lines in Japan. Initially, it was built to connect distant Japanese regions with Tokyo, the capital, in order to aid economic growth and development. Beyond long-distance travel, some sections around the largest metropolitan areas are used as a commuter rail network.[1][2] It is operated by five Japan Railways Group companies. A lineup of JR East Shinkansen trains in October Over the Shinkansen's 50-plus year history, carrying 2012 over 10 billion passengers, there has been not a single passenger fatality or injury due to train accidents.[3] Starting with the Tōkaidō Shinkansen (515.4 km, 320.3 mi) in 1964,[4] the network has expanded to currently consist of 2,764.6 km (1,717.8 mi) of lines with maximum speeds of 240–320 km/h (150– 200 mph), 283.5 km (176.2 mi) of Mini-Shinkansen lines with a maximum speed of 130 km/h (80 mph), and 10.3 km (6.4 mi) of spur lines with Shinkansen services.[5] The network presently links most major A lineup of JR West Shinkansen trains in October cities on the islands of Honshu and Kyushu, and 2008 Hakodate on northern island of Hokkaido, with an extension to Sapporo under construction and scheduled to commence in March 2031.[6] The maximum operating speed is 320 km/h (200 mph) (on a 387.5 km section of the Tōhoku Shinkansen).[7] Test runs have reached 443 km/h (275 mph) for conventional rail in 1996, and up to a world record 603 km/h (375 mph) for SCMaglev trains in April 2015.[8] The original Tōkaidō Shinkansen, connecting Tokyo, Nagoya and Osaka, three of Japan's largest cities, is one of the world's busiest high-speed rail lines. -

High-Speed Rail Journey to Japan

We are honored to present High-Speed Rail Journey to Japan Group 1: Sept 27 - Oct. 9, 2016 Group 2: Oct. 1 - Oct. 9, 2016 A custom Journey on behalf of Greetings from The Society of International Railway Travelers! We here at The Society of International Railway Travelers are honored to be asked yet again to design a fantastic study tour for members of the Midwest High Speed Rail Association (MWHSRA) -- this time to dynamic Japan! In cooperation with Rick Harnish, executive director, we have designed your journeys to France, Spain, France/Spain, Germany, China -- and we are thrilled to be offering this amazing new destination with its cutting-edge rail technology. On this journey, you will experience this technology and meet some of the decision-makers and designers of these amazing rail systems. Mr. Harnish is organizing a number of site visits which are not specific in this document. At this moment, they are a work in progress, and the rail partners in Japan await finalizing these visits until they know exactly how many are coming! But the numbers will be carefully limited to make this an important visit for you to learn -- and experience -- as much as you can on your High Speed Journey to Japan. Mr. Harnish is looking forward to your joining him in September! Please see the attached and call IRT to reserve! Sincerely, Eleanor Flagler Hardy President The Society of International Railway Travelers 800-478-4881 . The Society of International Railway Travelers on behalf of Midwest High Speed Rail Association In cooperation with our Virtuoso Japan partners, Windows to Japan 800-478-4881 [email protected] Midwest High Speed Rail Association Japan Tour Itinerary and Highlights Tour dates: Sept. -

Railways As World Heritage Sites

Occasional Papers for the World Heritage Convention RAILWAYS AS WORLD HERITAGE SITES Anthony Coulls with contributions by Colin Divall and Robert Lee International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) 1999 Notes • Anthony Coulls was employed at the Institute of Railway Studies, National Railway Museum, York YO26 4XJ, UK, to prepare this study. • ICOMOS is deeply grateful to the Government of Austria for the generous grant that made this study possible. Published by: ICOMOS (International Council on Monuments and Sites) 49-51 Rue de la Fédération F-75015 Paris France Telephone + 33 1 45 67 67 70 Fax + 33 1 45 66 06 22 e-mail [email protected] © ICOMOS 1999 Contents Railways – an historical introduction 1 Railways as World Heritage sites – some theoretical and practical considerations 5 The proposed criteria for internationally significant railways 8 The criteria in practice – some railways of note 12 Case 1: The Moscow Underground 12 Case 2: The Semmering Pass, Austria 13 Case 3: The Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, United States of America 14 Case 4: The Great Zig Zag, Australia 15 Case 5: The Darjeeling Himalayan Railway, India 17 Case 6: The Liverpool & Manchester Railway, United Kingdom 19 Case 7: The Great Western Railway, United Kingdom 22 Case 8: The Shinkansen, Japan 23 Conclusion 24 Acknowledgements 25 Select bibliography 26 Appendix – Members of the Advisory Committee and Correspondents 29 Railways – an historical introduction he possibility of designating industrial places as World Heritage Sites has always been Timplicit in the World Heritage Convention but it is only recently that systematic attention has been given to the task of identifying worthy locations. -

Japan's Railway Legacy

Feature From Meiji to the Present: Looking Back on 150 Years of Progress JAPAN’S RAILWAY LEGACY 1 Japan’s railways have made massive technological advances since the first line opened during the early Meiji Period. The superb rail network that TAMAKI KAWASAKI now extends across the country—with shinkansen (bullet trains) running as frequently as commuter trains—offers a treasure trove of technology and know-how that is also being exported overseas. AIL technology first reached day. The advent of the shinkansen cables were being laid, and the Japanese shores in 1853, in 1964 cut that time radically, and country feared being left behind R when Japanese people is now under two and a half hours— by accelerating markets and the were astounded by the technical spawning technology, techniques globalization of information sophistication of a model of a and know-how that Japan exports the transport and information Russian steam locomotive brought overseas. revolutions had enabled. When on a ship that landed in Nagasaki. Naofumi Nakamura, professor competition intensified in the Japan’s first train line opened nearly at The University of Tokyo’s global market, railway materials two decades later in 1872—twenty- Institute of Social Science, explains became cheaper and more nine kilometers of rail connecting that international factors greatly available, which boosted Japan’s Shimbashi in Tokyo with Yokohama. influenced the railway’s quick ability to purchase them. Many The railway became a symbol spread during the Meiji Period. leading overseas manufacturers of Japan’s efforts to Westernize, Japan’s drive to construct a railway from countries like England, and was even depicted in ukiyo-e began in earnest in 1869, the same the U.S. -

Part 2: Speeding-Up Conventional Lines and Shinkansen Asahi Mochizuki

Breakthrough in Japanese Railways 9 JRTR Speed-up Story 2 Part 2: Speeding-up Conventional Lines and Shinkansen Asahi Mochizuki Reducing Journey Times on is limited by factors such as curves, grades, and turnouts, so Conventional Lines scheduled speed can only be increased by focusing effort on increasing speed at these locations. Distribution of factors limiting speed Many of the intercity railways in Japan are lines in The maximum speed of any line is determined by emergency mountainous areas. So, objectives for increasing speeds braking distance. However, train speeds are also restricted by cannot be achieved by simply raising the maximum speed. various other factors, such as curves, grades, and turnouts. Acceleration and deceleration performance also impact Speed-up on curves journey time. The impact of each element depends on the The basic measures for increasing speeds on curves are terrain of the line. The following graphs show the distributions lowering the centre of gravity of rolling stock and canting the of these elements for the Joban Line, crossing relatively flat track. However, these measures have already been applied land, and for the eastern section of the Chuo Line, running fully; cant cannot be increased on lines serving slow freight through mountains. trains with a high centre of gravity. Conversely, increasing The graph for the Joban Line crossing the flat Kanto passenger train speed through curves to just below the limit Plain shows that it runs at the maximum speed of 120 km/h where the trains could overturn causes reduced ride comfort (M part) for about half the journey time. -

Transportation Museum in Tokyo and Railway Heritage Conservation Michio Sato

Feature World Railway Museums Transportation Museum in Tokyo and Railway Heritage Conservation Michio Sato Brief History of directly by the Secretariat’s Research old Manseibashi Station, but today’s Transportation Museum Institute of the Ministry of Railways and structure was built on the foundation of admission was free. This Secretariat’s the old station. However, a museum staff The history of the Transportation Museum Research Institute was a predecessor of member in charge of construction already at Tokyo dates back to 1911 when the current Railway Technical Institute recorded that the new building was Shimpei Goto (1857–1929), the Director- (RTRI). Soon after opening, the Museum imperfect as a museum facility owing to General of the Railway Agency (the was damaged by the 1923 Great Kanto budget limitations and location predecessor of Ministry of Railways and Earthquake, but it reopened about 2 years restrictions. During WWII, despite its Japanese National Railways), established later on 8 April 1925. Since space was central location, the Museum was the post of ‘officer in charge of railway limited because it was built under the miraculously lucky not be hit by bombs museum affairs’ with a view to elevated tracks, there were soon voices and its building and collections remained establishing a railway museum. What in favour of constructing a new building intact. However, it was closed prompted Goto to entertain such an idea elsewhere and moving the museum. At temporarily in March 1945 as air raids is unknown. However, the new post was about the same time, the size of became more intense. established just after many private Manseibashi Station in Kanda Suda-cho The Museum reopened on 25 January railways in Japan were nationalized and was cut and the freed grounds were 1946, soon after the war’s end when it new uniforms and badges had been made selected for the new museum site; this is was renamed the Museum of to give a sense of unity to the employees.