Background to the Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Year 2019 Budget

DELTA STATE Approved YEAR 2019 BUDGET. PUBLISHED BY: MINISTRY OF ECONOMIC PLANNING TABLE OF CONTENT. Summary of Approved 2019 Budget. 1 - 22 Details of Approved Revenue Estimates 24 - 28 Details of Approved Personnel Estimates 30 - 36 Details of Approved Overhead Estimates 38 - 59 Details of Approved Capital Estimates 61 - 120 Delta State Government 2019 Approved Budget Summary Item 2019 Approved Budget 2018 Original Budget Opening Balance Recurrent Revenue 304,356,290,990 260,184,579,341 Statutory Allocation 217,894,748,193 178,056,627,329 Net Derivation 0 0 VAT 13,051,179,721 10,767,532,297 Internal Revenue 73,410,363,076 71,360,419,715 Other Federation Account 0 0 Recurrent Expenditure 157,096,029,253 147,273,989,901 Personnel 66,165,356,710 71,560,921,910 Social Benefits 11,608,000,000 5,008,000,000 Overheads/CRF 79,322,672,543 70,705,067,991 Transfer to Capital Account 147,260,261,737 112,910,589,440 Capital Receipts 86,022,380,188 48,703,979,556 Grants 0 0 Loans 86,022,380,188 48,703,979,556 Other Capital Receipts 0 0 Capital Expenditure 233,282,641,925 161,614,568,997 Total Revenue (including OB) 390,378,671,178 308,888,558,898 Total Expenditure 390,378,671,178 308,888,558,898 Surplus / Deficit 0 0 1 Delta State Government 2019 Approved Budget - Revenue by Economic Classification 2019 Approved 2018 Original CODE ECONOMIC Budget Budget 10000000 Revenue 390,378,671,178 308,888,558,897 Government Share of Federation Accounts (FAAC) 11000000 230,945,927,914 188,824,159,626 Government Share Of FAAC 11010000 230,945,927,914 188,824,159,626 -

Accredited Healthcare Facilities

LIST OF DELTA STATE CONTRIBUTORY HEALTH SCHEME (DSCHS) ACCREDITED HEALTHCARE FACILITIES (Please, be informed that this list will be updated periodically) LGA NAME OF HCF OWNERSHIP CATEGORY ANIOCHA ONICHA-UKU PHC GOVERNMENT PRIMARY NORTH L.G.A ONICHA-OLONA PHC GOVERNMENT PRIMARY EZI PHC GOVERNMENT PRIMARY ISSELE-UKU PHC GOVERNMENT PRIMARY ISSELE-AZAGBA PHC GOVERNMENT PRIMARY UGBODU PHC GOVERNMENT PRIMARY ONICHA-UGBO PHC GOVERNMENT PRIMARY IDUMUJE-UGBOKO PHC GOVERNMENT PRIMARY ISSELE-UKU URBAN PHC GOVERNMENT PRIMARY OBOMKPA PHC GOVERNMENT PRIMARY UKWUNZU PHC GOVERNMENT PRIMARY UGBOBA PHC GOVERNMENT PRIMARY IDUMUJE-UNOR PHC GOVERNMENT PRIMARY OBIOR HCF ACCESS TO FINANCE PRIMARY GOVERNMENT HOSPITAL PRIMARY & GOVERNMENT ONICHA-OLONA SECONDARY GOVERNMENT HOSPITAL PRIMARY & GOVERNMENT ONICHA-UKU SECONDARY GOVERNMENT HOSPITAL PRIMARY & GOVERNMENT ISSELE-UKU SECONDARY ANIOCHA AZAGBA-OGWASHI PHC GOVERNMENT PRIMARY SOUTH L.G.A OTULU PHC GOVERNMENT PRIMARY OGWASHI-UKU PHC GOVERNMENT PRIMARY ADONTE PHC GOVERNMENT PRIMARY UBULU-UNOR PHC GOVERNMENT PRIMARY NSUKWA PHC GOVERNMENT PRIMARY UBULU-UKU PHC GOVERNMENT PRIMARY UBULU-OKITI PHC GOVERNMENT PRIMARY EJEME ANIOGOR PHC GOVERNMENT PRIMARY OLLOH PHC GOVERNMENT PRIMARY EWULU PHC GOVERNMENT PRIMARY GENERAL HOSPITAL PRIMARY & GOVERNMENT OGWASHI-UKU SECONDARY GOVERNMENT HOSPITAL PRIMARY & GOVERNMENT UBULU-UKU SECONDARY GOVERNMENT HOSPITAL PRIMARY & GOVERNMENT ISHEAGU SECONDARY BOMADI BOMADI PHC GOVERNMENT PRIMARY L.G.A OGBEIAMA PHC GOVERNMENT PRIMARY AKUGBENE PHCC GOVERNMENT PRIMARY OGO-EZE/EZEBIRI PHC GOVERNMENT -

Geoelectric Assessment of Ground Water Prospects and Vulnerability of Overburdened Aquifer in Oleh Delta State, Nigeria

International Journal of Applied Engineering Research ISSN 0973-4562 Volume 14, Number 3 (2019) pp. 806-820 © Research India Publications. http://www.ripublication.com Geoelectric Assessment of Ground Water Prospects and Vulnerability of Overburdened Aquifer in Oleh Delta State, Nigeria *Dr. Julius Otutu Oseji and Dr. James Chucks Egbai *Department of Physics, Faculty of Science, Delta State University, Abraka, Nigeria. Abstract To achieve this, a geophysical study is necessary in Oleh. Vertical Electrical Sounding using Schlumberger arrangement Hence the study was carried out not only to reveal the depth, was carried out in Oleh Community not only to assess the thickness of the aquifer and the lithological set up at Oleh groundwater potential but determine the vulnerability of the Community but evaluate the aquifer protective capacity of the overburdened aquifer and hence establish areas having high overlying formations and determine areas boreholes could be potential for appreciable and sustainable groundwater supply. sited for potable and sustainable water supply. Fourteen (14) stations were established and surveyed using a maximum current electrode separation of 300.00 m. The field LOCATION OF THE STUDY AREA (OLEH) data obtained was first analyzed by curve matching before computer iteration. The result showed that apart from the Oleh is located in Isoko South Local Government Area of 0 1 11 locations in VES 5, 6, 7 and 11 that has shallow aquifer and Delta State, Nigeria. It lies between Latitudes 05 26 16 E 0 1 11 0 1 11 0 1 may be easily contaminated; boreholes could be sited in every to 05 29 55 E and Longitudes 06 11 11 N to 06 13 11 other location to a depth of 35.00 m at the 4th layer for potable 54 N. -

List of Coded Health Facilities in Delta State.Pdf

DELTA STATE HEALTH FACILITY LISTING WARD NAME OF HEALTH FACILITY FACILITY TYPE LGA GEN. HOSPITAL ISSELE-UKU SECONDARY GLORY TO GOD MEDICAL CLINIC,PRIMARY ISSELE-UKU ST. THERESA’S CLINIC & PRIMARY ISSELE-UKU(1) MATERNITY, ISSELE-UKU GEN. HOSPITAL ONICHA-UKU SECONDARY PHC ONICHA-UKU PRIMARY PHC OBIOR PRIMARY CHRISTY MAT. HOME, OBIOR PRIMARY OBIOR/ONICHA-UKU ONICHA-UGBO PHC ONICHA-UGBO PRIMARY PHC IDUMUJE-UGBOKO PRIMARY PHC IDUMUJE-UNOR PRIMARY HP ANIOFU PRIMARY IDUMUJE PHC OBOMKPA PRIMARY HP UGBOBA PRIMARY OKWUOFU MAT. HOME, PRIMARY OBAMKPA OBOMKPA PHC IDUMUOGO PRIMARY PHC UGBODU PRIMARY PHC UBULUBU PRIMARY PHC UKWUZU PRIMARY MATERNITY HOME, UBULUBU PRIMARY UGBODU PHC ISSELE-MKPITIME PRIMARY ANIOCHA NORTH ANIOCHA PHC ISSELE-AZAGBA PRIMARY FLORA MAT. HOME, ISSELE- PRIMARY ISSELE-MKPITIME AZAGBA PHC ONICHA-OLONA PRIMARY ONICHA-OLONE GEN. HOSPITAL ONICHA-OLONESECONDARY PHC EZI PRIMARY PHC OGORDO PRIMARY STAR OF HOPE MAT. HOME, PRIMARY EZI EZI ANIOCHA NORTH ANIOCHA PHC ISSELE-UKU PRIMARY HP ISSELE-UKU PRIMARY PILGRIM BAPTIST HOSP, SECONDARY ISSELE-UKU ISSELE-UKU(2) AJULU CLINIC, ISSELE-UKU PRIMARY FAITH MAT. HOME ONICHA- PRIMARY UGBO ST. MONICA MAT. HOME PRIMARY ONICHA- UGBO ONICHA-UGBO GEN. HOSPITAL OGWASHI-UKUSECONDARY PHCC OGWASHI-UKU PRIMARY HOPE CLINIC & MATERNITY OGWASHI-UKUPRIMARY EJEKS CLINIC OGWASHI-UKU PRIMARY NOVA SPECIALIST HOSPITAL OGWASHI-UKUSECONDARY AGIADIASI ST MARY HOSPITAL OGWASHI-UKUSECONDARY PHCC ADONTE PRIMARY PHCC UKWUOBA PRIMARY ADONTE PHCC UMUTE PRIMARY GEN. HOSPITAL UBULU-UKU SECONDARY ST. ANTHONY MAT. HOME UBULU-UKUPRIMARY UBULU-UKU 1 TRINITY HOSPITAL & MATERNITYSECONDARY UBULU-UKU PHCC UBULU-UKU PRIMARY ANGLICAN MAT. UBULU-UKU PRIMARY UBULU-UKU 2 HOPE MAT. HOME AKUE QTRS.PRIMARY UBULU-UKU UBULU-OKITI 2 PHCC UBULU-OKITI PRIMARY PHCC UBULU-UNOR PRIMARY UBULU-UNOR PHCC ASHAMA PRIMARY GOVT HOSPITAL ISHEAGU SECONDARY PHCC ISHEAGU PRIMARY PHCC OLODU PRIMARY PHCC EWULU PRIMARY EWULU/ISHEAGU PHCC ABAH UNOR PRIMARY PHCC NSUKWA PRIMARY NSUKWA EMMA. -

Agricultural Economics and Extension Research Studies (AGEERS) Vol 6 No.2,2018

AGRICULTURAL ECONOMICS AND EXTENSION RESEARCH STUDIES (AGEERS) A G E E R S 2018, Vol 6, No.2 Promoting Agricultural Research AGRICULTURAL ECONOMICS AND EXTENSION RESEARCH STUDIES Promoting Agricultural Research Vol. 6, No.2 ISSN: 2315-5922 2018 A PUBLICATION OF THE DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURAL ECONOMICS AND EXTENSION, UNIVERSITY OF PORT HARCOURT, NIGERIA AGRICULTURAL ECONOMICS AND EXTENSION RESEARCH STUDIES AGEERS VOLUME 6 (2), 2018 ISSN: 2315 – 5922 A Publication of the Department of Agricultural Economics and Extension Faculty of Agriculture, University of Port Harcourt PMB 5323, Choba, Rivers State, Nigeria C 2018. Department of Agricultural Economics and Extension Faculty of Agriculture, University of Port Harcourt, Nigeria EDITORIAL BOARD Editor – in – chief Professor A.C. Agumagu Managing Editor Dr. A. Henri-Ukoha Senior Editors Prof. O.M. Adesope Dr. A.O. Onoja Editors Dr. O.N. Nwaogwugwu Dr. M.E. Ndubueze-Ogaraku Dr. P. A. Ekunwe Dr. C.C. Ifeanyi-obi Associate Editors Ms. O. Jike – Wai Dr. Z. A. Elum Assistant Editors Dr. A.I. Emodi Dr. E. B. Etowa Dr. V.C. Ugwuja Consulting Editors Prof. E. P. Ejembi Federal University of Agriculture, Makurdi, Nigeria Prof. V. I. Fabiyi Ladoke Akintola University, Ogbomosho, Nigeria Prof. E.A. Allison-Oguru Niger Delta University, Amasoma, Nigeria Prof. J.S. Orebiyi Federal University of Technology, Owerri, Nigeria Prof. O.O. Oladele North West University, Mafikeng, South Africa Prof. IniAkpabio University of Uyo, Nigeria Prof. C.U. Okoye University of Nigeria, Nsukka Prof. S. Rahman Nasarawa State University, Keffi, Nigeria Prof. A.O. Angba University of Calabar, Nigeria Dr. D.I. Ekine Rivers State University Prof. -

NIDPRODEV Donates Livelihood Recovery Items to Flood Disaster

NGO DONATES LIVELIHOOD RECOVERY ITEMS TO FLOOD VICTIMS In order to avert famine following the recent flood that devastated farming and rendered many farmers homeless in Delta State, a non-governmental organization, Niger Delta Professionals for Development (NIDPRODEV) through funding from Oxfam Novib, Netherlands has brought succor to farmers in four communities in Isoko South Local Government Area affected by the recent flood. The donations included thousands of improved cassava stems, herbicides, knapsack sprayers, nose masks, fish fingerlings and fertilizers. NIDPRODEV has also carried out soil assessment in these communities to determine soil fertility and quality after the flood in order to ensure that farmers receive all of the necessary inputs to grow quality crops. Making the donation to the people of Enhwe, Uzere, Aviara and Idheze communities, Mr. Jerry Nwigwe and Ms. Ifeoma Olisakwe of NIDPRODEV as well as Mr. Austin Terngu of Oxfam Novib, informed the people that the gesture was part of their humanitarian effort aimed to alleviate some of the hardship that farmers in the area are currently experiencing. The efforts of these two organizations are partly through livelihood recovery items as the flood has devastated their sources of livelihood and reduce crop yield. The representatives from these organizations pledged the continuous assistance to the communities in this planting season and urged the people to work hard to ensure that they make optimum use of the items.Representatives of the communities who received the items on behalf of the people, Mr Oghomu Samson (Enhwe) and Mr Akasi Festus (Uzere), conveyed the pleasure of the people to the NIDPRODEV and Oxfam Novib and promised that the farmers would make good use of the items. -

Climate Change Are Real

CASECASE STUDY STUDY ARTICLE 4(16), October- December, 2018 ISSN Climate 2394–8558 EISSN 2394–8566 Change Determinants of Access and Utilization of Climate Services among Vulnerable Communities: A Case Study of Isoko Communities in Delta State, Nigeria Onwuemele Andrew Changes in climate have caused impacts on natural and human systems. These impacts affect poor people’s lives through impacts on livelihoods and destruction of homes. In Delta State, the impacts of climate change are real. Adaptation has been identified as the key to reducing the impacts of climate change. However, successful adaptation depends on use of climate services. While climate services are essential to adaptation, the services do not always reach the users who need it most. This paper analyses factors influencing access and utilization of climate services in Delta state, Nigeria. The paper utilized the survey research while data were analyzed using both descriptive and inferential statistics. Findings show low utilization of climate service. The determinants of access and utilization of climate services include income, educational attainments, access to ICT facilities, extension agents and the level of local climate variability. The paper calls for awareness creation on the importance of climate services. INTRODUCTION Temperature Globally, climate change has constituted a serious threat to development The assessment also reveals that that in the long term, there was gains in the last decades. It has negatively impacted on both human and temperature increase in several parts of the country with the exception of natural systems generating adverse consequences for living organisms areas around the Jos Plateau while the largest increase in temperature especially human beings (IPCC, 2014). -

Approved Year 2020 Revised Capital Budget

Approved Year 2020 Revised Capital Budget ADMINISTRATIVE SECTOR Directorate of Government House & Protocol BUSINESS Approved 2020 Approved 2020 Budget Code Budget Line Item AREA Fund Fund Center Commitment Item Function Code Funded Program Budget Revised Budget Approved 2019 Budget 0111020001 Security 426. 02101 F101010000 00023050122 70111 00220000010108 280,000,000 200,000,000 800,000,000 0111020002 Beautification of Selected Cities 426. 02101 F101010000 00023050124 70111 00090000010110 400,000,000 200,000,000 250,000,000 0111020003 Girl Child Enterpreneurship Programme 210. 02101 F101010000 00022020503 70133 00070000010106 400,000,000 400,000,000 0111020004 Social Security 426. 02101 F101010000 00023050122 70111 00220000010108 1,000,000,000 2,000,000,000 728,000,000 0111020005 Purchase of medical equipment for the Govt House Clinic 426. 02101 F101010000 00031050102 70111 00040000010102 14,471,550 14,471,550 25,000,000 0111020006 Library 426. 02101 F101010000 00031050108 70111 00220000010104 2,000,000 2,000,000 5,000,000 0111020007 Uniforms 426. 02101 F101010000 00022020309 70111 00220000010105 3,030,000 3,030,000 5,000,000 0111020008 Govt House Resource/Research center 426. 02101 F101010000 00032010501 70111 00220000010109 12,443,330 12,443,330 15,000,000 0111020009 Rehabilitation/Repairs of Special Edit Centre 426. 02101 F101010000 00031050418 70111 00220000010104 5,000,000 5,000,000 20,000,000 0111020010 Minor Works 426. 02101 F101010000 00031050418 70111 00220000010104 74,042,396 74,042,396 86,000,000 0111020011 Purchase of Vehicles and Boats 426. 02101 F101010000 00032010405 70111 00220000010102 2,011,766,500 1,305,730,086 2,006,448,607 0111020012 Purchase of office Equipment 426. -

(Formerly NIDPRODEV Situation Report) FLOOD RAVAGES NGO PROJECTS' COMMUNITIES in the NIGER DELTA If Urgent Attention Is N

LITE (Formerly NIDPRODEV Situation Report) FLOOD RAVAGES NGO PROJECTS’ COMMUNITIES IN THE NIGER DELTA If urgent attention is not given to the ravaging flood which has post serious threat to the inhabitants in the Niger Delta region, the relative peace experienced in the last few years will be a mirage. Though the flooding is acclaimed to be a national issue, the impact and magnitude of it in the Niger Delta region is quite monumental compared to what is happening in other regions of Nigeria. A nongovernmental organization, Leadership Initiative for Transformation and Empowerment (LITE-Africa) formerly Niger Delta Professionals for Development (NIDPRODEV) on a daily basis gives situation reports of communities where it operates. Field officers visits to the communities indicate that all its project communities have been overwhelmed by the heavy floods. This has affected the socio-economic status of the people in the communities. Economic livelihoods have been destroyed which is forcing people to make premature harvest of crops that have been overcome by the flood and other livelihood systems such as fish pond, poultry and livestock were destroyed and businesses stalled. The flood is also forcing people to leave their homes and take refuge in camps with little or no food, properties worth billions of naira have been lost to the floods, schools have been closed down indefinitely, and inter-state movement stalled with prices of food stuff sky-rocketing. Furthermore, commercial motor bike operators are charging exorbitant fares to transport people across flooded roads. Some of our project communities affected by the flood resulting to inaccessibility include but are not limited to: Ekowe, Oporoma , and Amassoma in Southern Ijaw LGA; Kiama in Kolokuma/Opukuma LGA in Bayelsa State; Emede, Aviara, Idheze, Uzere, Enwhe and Igbide in Isoko South LGA; and neighboring communities of Ozoro, Ada, Oyede, Orie, and Ofagbe in Isoko North LGA in Delta State. -

The Non-Farm Sector As a Catalyst for Poverty Reduction in the Niger-Delta Region, Nigeria

THE NON-FARM SECTOR AS A CATALYST FOR POVERTY REDUCTION IN THE NIGER-DELTA REGION, NIGERIA ONWUEMELE, ANDREW Nigerian Institute of Social and Economic Research (NISER) Social and Governance Policy Research Department Tel: 234-08028935767; 08130569041 Email: [email protected] Abstract The Niger-Delta region is the home of oil exploration in Nigeria. Over the years, the exploration of oil in the region has created several environmental problems. The increasing level of environmental degradation in the region has brought about pollution of water bodies and land which are the most important livelihood assets of the people. Thus, crop production and fishing which are the main livelihood activities of the people can no longer sustain the domestic needs of most rural households in the region. The quality of life in these communities has worsened as large numbers of the subsistent farmers are now edged out of the production circuit. To supplement income from the farm sector since the rural households must survive, this study therefore, assesses the role of the non-farm sector in the sustenance of the rural households. The survey research design was adopted. One state (Delta state) in the Niger-Delta was randomly selected for the study. The study covers two Local Councils in the state (Isoko North and South). Nineteen rural wards were purposively used for the study out of the twenty-four wards in the two councils. One community each was randomly selected from each ward. Both primary and secondary sources of data were utilized. The systematic sampling with a random start and a sampling interval of five was used in selecting the final respondents. -

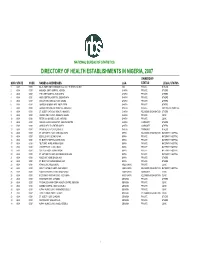

Directory of Health Establishments in Nigeria, 2007 Ownership S/No

NATIONAL BUREAU OF STATISTICS DIRECTORY OF HEALTH ESTABLISHMENTS IN NIGERIA, 2007 OWNERSHIP S/NO. STATE CODE NAMES & ADDRESSES LGA STATUS LEGAL STATUS 1 ABIA 00001 IDEAL HOSP. NO3 COUNCIL STREET OFF 91 OHAKU RD ABA ABA PRIVATE OTHERS 2 ABIA 00001 AKAHABA JOINT HOSPITAL. ABIRIBA OHAFIA PRIVATE OTHERS 3 ABIA 00001 THE LIGHT HOSPITAL. ELU OHAFIA OHAFIA PRIVATE OTHERS 4 ABIA 00001 MBEN CENTRAL HOSPITAL. EBEM OHAFIA OHAFIA PRIVATE OTHERS 5 ABIA 00001 KING OF KING SPECIAL HOSP. ASABA OHAFIA PRIVATE OTHERS 6 ABIA 00001 JOHNSON OSONWA MED. HOSP. EBEM OHAFIA PRIVATE OTHERS 7 ABIA 00001 UZONDU PSYCHIATRIC HOSPITAL. AMACKPU OHAFIA PRIVATE PSYCHIATRIC HOSPITAL 8 ABIA 00001 ST. JOSEPH CATHOLIC HEALTH. AMACKPU OHAFIA RELIGIOUS ORGANISATION OTHERS 9 ABIA 00001 UZONDU POLY CLINIC. AMAEKPU. OHAFIA OHAFIA PRIVATE CLINIC 10 ABIA 00001 PETER UKA OJI MED. CLINIC. NKPORO OHAFIA PRIVATE CLINIC 11 ABIA 00001 ISIUGWU OHAFIA JONES PRY. HEALTH CENTRE OHAFIA COMMUNITY OTHERS 12 ABIA 00001 OHAFOR HEALTH CENTRE OHAFIA OHAFIA COMMUNITY OTHERS 13 ABIA 00001 OKAMU HEALTH CENTRE OHAFIA OHAFIA COMMUNITY OTHERS 14 ABIA 00001 ST. ANTHONY'S MAT. HOME ASA UKWA UKWA RELIGIOUS ORGANISATION MATERNITY HOSPITAL 15 ABIA 00001 EZEVILLE MAT. UZUAKU UKWA UKWA PRIVATE MATERNITY HOSPITAL 16 ABIA 00001 ST. MARY'S HOSPITAL OGWE UKWA UKWA PRIVATE MATERNITY HOSPITAL 17 ABIA 00001 TILY'S MAT. HOME AKIRIKA NDOKI UKWA PRIVATE MATERNITY HOSPITAL 18 ABIA 00001 CHINYERE MAT. CLINIC UKWA UKWA PRIVATE MATERNITY HOSPITAL 19 ABIA 00001 COTTAGE HOSP. AZUMIRI NDOKI UKWA PRIVATE MATERNITY HOSPITAL 20 ABIA 00001 ST. ANTHONY'S HOSP. UMUEBULU NAWU ABA UKWA PRIVATE MATERNITY HOSPITAL 21 ABIA 00001 NGOZI MAT. -

SURNAME FIRSTNAME ADRESS LGA GENDER DEGREE PROGRAM 1 ANITA EJOMERIONA OPPOSITE HIGH COURT of JUSTICE, OFF IDC ROAD OLEH Isoko So

SURNAME FIRSTNAME ADRESS LGA GENDER DEGREE PROGRAM 1 ANITA EJOMERIONA OPPOSITE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE, OFF IDC ROAD OLEH Isoko South Delta State F HND N-Agro 2 Imonifano Esther 29 IDC Road, Oleh Delta State Isoko South Delta State F BSc N-Agro 3 ARUORIWO OWEWE 29 AMAWA STREET, OLEH Isoko South Delta State F BSc N-Agro 4 OHWOKA LUCKY 1, OHWOKA CLOSE AVIARA, ISOKO SOUTH. Isoko South Delta State F HND N-Agro 5 Esieba Omamuzo 16 Okemu Street off Iwhrekpokpor road, Ughelli Isoko South Delta State F HND N-Agro 6 Joyce Iferobia 8 michael amadi rukpakwulusi newlayout ph rivers state Isoko South Delta State F BSc N-Agro 7 OFFICE CLEMENTINA No. 27 Agbama Street, Oleh Isoko South Delta State F BSc N-Agro 8 OGBOGHRO ONYISI NO. 4 OVIEBA STREET, OLEH Isoko South Delta State F HND N-Agro 9 NWOSU JOANNA NO. 2B, ONUIYI LIND ROAD, NSUKKA Isoko South Delta State F BSc N-Agro 10 Godwin Samuel 17, Iyare Quarter, Enhwe, Isoko South LGA, Delta State Isoko South Delta State M HND N-Agro 11 SYLVESTER ITIMI 24 Itimi Road, Irri Town, Isoko South, Delta State. Isoko South Delta State M BEng N-Agro 12 EVAWERE ORAHEMO 7 Agbajileke street Oleh, Delta state Isoko South Delta State M HND N-Agro 13 Marro Unuive 5 Erebi lane,Oleh Isoko South Delta State M BSc N-Agro 14 CHRISTIAN OGHRE OPPOSITE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE, OFF IDC ROAD OLEH Isoko South Delta State M HND N-Agro 15 IGBAMA REUBEN No 97 Iwhrekpokpor Road, Ughelli Isoko South Delta State M HND N-Agro 16 FELIX EDHERAKA 4, Ekregbo street, Eviewho Qtrs Irri Isoko South Delta State M BSc N-Agro 17 Umukoro Odaro-Junior 23 Ogbemudia Road, Oleh Isoko South Delta State M BSc N-Agro 18 Dennis Obaduemu No 4 Igbide Emede Road Igbide Isoko South Delta State M HND N-Agro 19 IGHOBURO MIKE OGBUKU QAURTERS, IKPIDE-IRRI Isoko South Delta State M HND N-Agro 20 OMONUKU EDWIN No.