ABSTRACT BUTLER, JAY. Monastic Revival In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2011 Vol 20 No 1 AIM Newsletter

The Unitedaim States Secretariat of the Alliance usa for International Monasticism www.aim-usa.org Volume 20 No. 1 2011 [email protected] AIM USA New AIM USA Board Member Lent 2011 Grants Sr. Karen Joseph, OSB, member Your support enables us to fund the following requests this year. of the Sisters of St. Benedict in • bread baking machine, Benedictine sisters in Twasana, Ferdinand, Indiana, has joined the South Africa AIM USA Board of Trustees. Sr. • a scholarship for studies for a formation director, OCist Karen, formerly a member of the monks in Vietnam Benedictine Sisters of Perpetual Adoration, Clyde, MO, has served in • jam processing equipment, Cistercian sisters in Ecuador various leadership roles throughout • spirituality books in Portuguese, Benedictine and Cistercian her monastic life, has been involved monastics in Brazil & Angola in committees on the international • monastic studies and secondary education, Benedictine and level within the Benedictine Order Cistercian sisters in Africa and has given retreats and workshops in Benedictine spirituality to Benedictines throughout North America. She has participated in the Monastic Studies Program at St. John’s, Collegeville, MN and has served as a staff member of the Benedictine Women’s Rome Renewal Program for the past four years. Sister Karen works in the Spirituality Ministry Program of the Ferdinand Benedictines. This year, due to increasing postage and printing costs, AIM will be printing and mailing only two issues of the newsletter. The third issue (SUMMER) BREAD BAKING MACHINE—BENEDICTINE SISTERS, TWASANA, will be published only online. SOUTH AFRICA—Sister Imelda with Sister Martin and two novices in PLEASE SEND US the bakery. -

A Monestary for the Brothers of the Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance of the Rule of St

Clemson University TigerPrints Master of Architecture Terminal Projects Non-thesis final projects 12-1986 A Monestary for the Brothers of the Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance of the Rule of St. Benedict. Fairfield ounC ty, South Carolina Timothy Lee Maguire Clemson University Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/arch_tp Recommended Citation Maguire, Timothy Lee, "A Monestary for the Brothers of the Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance of the Rule of St. Benedict. Fairfield County, South Carolina" (1986). Master of Architecture Terminal Projects. 26. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/arch_tp/26 This Terminal Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Non-thesis final projects at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Architecture Terminal Projects by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A MONASTERY FOR THE BROTHERS OF THE ORDER OF CISTERCIANS OF THE STRICT OBSERVANCE OF THE RULE OF ST. BENEDICT. Fairfield County, South Carolina A terminal project presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University in partial fulfillment for the professional degree Master of Architecture. Timothy Lee Maguire December 1986 Peter R. Lee e Id Wa er Committee Chairman Committee Member JI shimoto Ken th Russo ommittee Member Head, Architectural Studies Eve yn C. Voelker Ja Committee Member De of Architecture • ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . J Special thanks to Professor Peter Lee for his criticism throughout this project. Special thanks also to Dale Hutton. And a hearty thanks to: Roy Smith Becky Wiegman Vince Wiegman Bob Tallarico Matthew Rice Bill Cheney Binford Jennings Tim Brown Thomas Merton DEDICATION . -

CALLAN PARISH NEWSLETTER Readers: 6.30 P.M. Lizzy Keher

CALLAN PARISH NEWSLETTER parish. This course takes place Tues. & Thur. 7-9 p.m. in conjunction with NUI Maynooth. It takes place over one academic year and is often a Readers: 6.30 p.m. Lizzy Keher, 8.30 a.m. Tommy Quinlan; 11.00 springboard for people trying to discern if they have a vocation to a.m. Joe Kennedy priesthood or religious life. It is divided up into 6 Modules: Scripture, Moral Theology; History of the Church; Liturgy & Sacraments; Living one’s Faith. Very generous response to Emergency Trocaire Collection last A former participant at the course describes it as ‘compelling, illuminating weekend: Famine and starvation are again stalking East and life-enhancing’ (it) strikes the right balance between teaching and Africa i.e. Ethiopia, Somalia, South Sudan and parts of Kenya. Global encouraging lively discourse and debate thus promoting an informal and warming is reeking havoc on the most vulnerable people of our world – convivial environment in which to interact and receive and assimilate those living in closest proximity to desert regions. The desert is knowledge’. Fee for the full year - €400. For further information please encroaching more and more into areas that areas that could previously be contact Declan Murphy; email: [email protected] cultivated and yield a crop or support a few goats etc.. 25 million people or [email protected] tel. 056-7753624 or 087-9081470. are facing starvation. Last weekend an emergency collection was taken up for Trócaire who is already in there on the ground supporting up to Places of Pilgrimage: Mount Melleray Abbey, near Cappoquin, 100,000 people. -

The Maronite Catholic Church in the Holy Land

The Maronite Catholic Church in the Holy Land The maronite church of Our Lady of Annunciation in Nazareth Deacon Habib Sandy from Haifa, in Israel, presents in this article one of the Catholic communities of the Holy Land, the Maronites. The Maronite Church was founded between the late 4th and early 5th century in Antioch (in the north of present-day Syria). Its founder, St. Maron, was a monk around whom a community began to grow. Over the centuries, the Maronite Church was the only Eastern Church to always be in full communion of faith with the Apostolic See of Rome. This is a Catholic Eastern Rite (Syrian-Antiochian). Today, there are about three million Maronites worldwide, including nearly a million in Lebanon. Present times are particularly severe for Eastern Christians. While we are monitoring the situation in Syria and Iraq on a daily basis, we are very concerned about the situation of Christians in other countries like Libya and Egypt. It’s true that the situation of Christians in the Holy Land is acceptable in terms of safety, however, there is cause for concern given the events that took place against Churches and monasteries, and the recent fire, an act committed against the Tabgha Monastery on the Sea of Galilee. Unfortunately in Israeli society there are some Jewish fanatics, encouraged by figures such as Bentsi Gopstein declaring his animosity against Christians and calling his followers to eradicate all that is not Jewish in the Holy Land. This last statement is especially serious and threatens the Christian presence which makes up only 2% of the population in Israel and Palestine. -

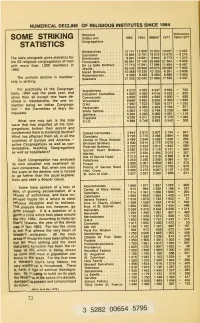

Some Striking

NUMERICAL DECLINE OF RELIGIOUS INSTITUTES SINCE 1964 Religious Difference SOME STRIKING Orders and 1964/1977 STATISTICS Congregations Benedictines 12 131 12 500 12 070 10 037 -2 463 Capuchins 15 849 15 751 15 575 12 475 - 3 276 - The table alongside gives statistics for Dominicans 9 991 10091 9 946 8 773 1 318 the 62 religious congregations of men Franciscans 26 961 27 140 26 666 21 504 -5 636 17584 11 484 - 6 497 . 17 981 with more than 1,000 members in De La Salle Brothers . 17710 - Jesuits 35 438 35 968 35 573 28 038 7 930 1962. - Marist Brothers 10 068 10 230 10 125 6 291 3 939 Redemptorists 9 308 9 450 9 080 6 888 - 2 562 uniform decline in member- - The Salesians 21 355 22 042 21 900 17 535 4 507 ship is striking. practically all the Congrega- For Augustinians 4 273 4 353 4 447 3 650 703 1964 was the peak year, and 3 425 625 tions, . 4 050 Discalced Carmelites . 4 050 4016 since then all except one have de- Conventuals 4 650 4 650 4 590 4000 650 4 333 1 659 clined in membership, the one ex- Vincentians 5 966 5 992 5 900 7 623 7 526 6 271 1 352 ception being an Indian Congrega- O.M.I 7 592 Passionists 3 935 4 065 4 204 3 194 871 tion - the Carmelites of Mary Im- White Fathers 4 083 4 120 3 749 3 235 885 maculate. Spiritans 5 200 5 200 5 060 4 081 1 119 Trappists 4 339 4 211 3819 3 179 1 032 What, one may ask, is this tidal S.V.D 5 588 5 746 5 693 5 243 503 wave that has engulfed all the Con- gregations, broken their ascent and condemned them to statistical decline? Calced Carmelites ... -

St Declan's Well and on to the Round Tower Before Breakfast

_____________________________________________________________________________________________ St Declan’s Way - 7 Day Irish Camino, Sunday 26th September to Saturday 2nd October 2021 “Our Lady’s Hospice & Care Services are delighted to be the first charity to undertake the Irish Camino ‘St Declan’s Way’ which predates the Spanish Camino by circa 400 years. This will be a very special and unique experience for our supporters, taking them 100 kms down paths trodden by saints of old, past castles and forts, holy wells and breath-taking views...” Emily Barton, Senior Manager Public Fundraising _____________________________________________________________________________________________ The 100 kms (62 miles) ancient path of St. Declan’s Way is very much a journey back in time linking the ancient ecclesiastical centres of Ardmore in County Waterford and Cashel in County Tipperary. St Declan brought Christianity to the Déise region of Waterford around 415 AD shortly before the arrival of St. Patrick to Ireland. St Patrick did not come further south than Cashel in his mission to bring the Christian story to the people of Ireland. St. Declan left Ardmore in Waterford and made the return journey to Cashel to meet St. Patrick on many occasions and so the pilgrim route was born. St Declan’s Way remains faithful to the medieval pilgrimage and trading routes etched out on the landscape through the centuries. Following these ancient trails with Dr Phil and Elaine will leave imprints that will last a lifetime. On our Camino, we quite literally walk in the steps of those who have gone before. When our own stories merge with the stories of old, it is then the magic happens. -

Archivio Generale St. Louis Province

INVENTORY OF THE ST. LOUIS PROVINCE COLLECTION (12) REDEMPTORIST GENERAL ARCHIVE, ROME Prepared by Patrick J. Hayes, Ph.D., Archivist Redemptorist Archives of the Baltimore Province 7509 Shore Road Brooklyn, New York, USA 11209 718-833-1900 Email: [email protected] The Redemptorists’ Denver Province (12) has a historic beginning and storied career. Formally erected as a sister province of the Baltimore Province in 1875, it was initially known as the Vice-Province of St. Louis. It eventually divided again between regional foundations in Chicago, New Orleans, and Oakland. The Denver Province presently affiliates with the Vice- Provinces of Bangkok and Manaus and hosts the external province of Vietnam. Today, the classification system at the Archivio Generale Redentoristi (AGR), has retained the name of the original St. Louis Province in identifying the collection associated with this unit of the Redemptorist family. A good place to begin to understand the various permutations of the St. Louis Province is through the work of Father Peter Geiermann’s Annals of the St. Louis Province (1924) in three thick volumes. Unfortunately, it has never been updated. The Province awaits its own full-scale history. The St. Louis Province covered a large swath of the United States at one point—from Whittier, California to Detroit, Michigan and Seattle, Washington to New Orleans, Louisiana. Redemptorists of this province were present in cities such as Wichita and Kansas City, Fresno and Grand Rapids, San Francisco and San Antonio. Their formation houses reached into Missouri, Illinois, and Wisconsin. Schools could be found in Oakland and Detroit. Their shrines in Chicago, New Orleans, and St. -

May 26, 2000 Vol

Inside Archbishop Buechlein . 4, 5 Editorial. 4 From the Archives. 25 Question Corner . 11 TheCriterion Sunday & Daily Readings. 11 Criterion Vacation/Travel Supplement . 13 Serving the Church in Central and Southern Indiana Since 1960 www.archindy.org May 26, 2000 Vol. XXXIX, No. 33 50¢ Two men to be ordained to the priesthood By Margaret Nelson His first serious study of religion was of 1979—four months into the Iran civil his sister and her husband when he was 6 Islam, when he began to teach in Saudi war. years old. Archbishop Daniel M. Buechlein will Arabia. A history professor there, “a wise “I approached the nearest Catholic At his confir- ordain two men to the priesthood for the man from Iraq” who spoke fluent English, Church—St. Joan of Arc in Indianapolis.” mation in 1979, Archdiocese of Indianapolis at 11 a.m. on talked with him He asked Father Donald Schmidlin for Borders didn’t June 3 at SS. Peter and Paul Cathedral in about his own instructions. Since that was before the think of the Indianapolis. faith. Rite of Christian Initiation of Adults priesthood. He They are Larry Borders of St. Mag- “He knew process was so widespread, he met with had been negoti- dalen Parish in New Marion—who spent more about the priest and two other men every week ating a teaching two decades overseas teaching lan- Christianity than or so. job in Japan to guages—and Russell Zint of St. Monica I knew about The week before Christmas in 1979, begin a 15-year Parish in Indianapolis—who studied engi- my own tradi- Borders was confirmed into the Catholic contract. -

Ai266 Mount-Melleray-Abbey.Pdf

01 MOUNT MELLERAY ABBEY ARCHITECTS - dhbArchitects Fintan Duffy (project director); Eddie Phelan, Hein Raubenheimer, Harry Bent, Máire Henry, Shane O’Connor, June Bolger, Emma Carvalho, Mark Fleming, Ed Walsh CLIENT - Cistercian Order STRUCTURAL ENGINEERS - Frank Fox and Associates MECHANICAL AND ELECTRICAL CONSULTANTS - Ramsay Cox Associates QUANTITY SURVEYORS - Grogan Associates MAIN CONTRACTOR - Clancy Construction PHOTOGRAPHER - Philip Lauterbach Project size - 1,300m2 Value - e3m Duration - 15 months Location - Cappoquin, Co. Waterford Report by Fintan Duffy, dhbArchitects Mount Melleray is a functioning monastery of the Cistercian institutional feel of the existing building with its long corridors order which has important historical and literary associations. and poorly lit cloister has been softened and brightened by the It is a protected structure with a rating of national importance. introduction of glazed openings at the end of each axis, with This project required the rebuilding and reordering of part of views to the surrounding gardens. Aspects of the monastic the monastery to provide new accommodation facilities for the life such as rigour and community are expressed in the ordered monks. The monks, many of whom are elderly, had been living layout of the cells and spaces while its contemplative nature is scattered throughout the sprawling complex of mainly early suggested by disconnecting these from the ground plane and 19th century buildings, with little or no amenities or modern facing them westwards. The mountain on which the monastery services. The primary aim of the project was to restore a sense is built is mirrored in the rising line of the rebuilt retaining wall of community by gathering all its members under one roof and outside the new chapel and the Cistercians’ respect for the providing basic comforts in self-contained rooms. -

The Writing and Reception of Catherine of Siena

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 6-2017 Lyrical Mysticism: The Writing and Reception of Catherine of Siena Lisa Tagliaferri Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2154 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] LYRICAL MYSTICISM: THE WRITING AND RECEPTION OF CATHERINE OF SIENA by LISA TAGLIAFERRI A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Comparative Literature in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2017 © Lisa Tagliaferri 2017 Some rights reserved. Except where otherwise noted, this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial 4.0 International License. Images and third-party content are not being made available under the terms of this license. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ ii Lyrical Mysticism: The Writing and Reception of Catherine of Siena by Lisa Tagliaferri This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Comparative Literature in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. 19 April 2017 Clare Carroll Chair of Examining Committee 19 April 2017 Giancarlo Lombardi Executive -

St. Declan's Well to Mark the Moment

_______________________________________________ St. Declan’s Way - 7 Day Irish Camino Camino|Pilgrim paths|Scenic trails|Celtic story & song| Ancient castles|Reflective ‘compass points’ along the way| Where old meets now! _________________________________________________________________ The 100 km (62 mile) ancient path of St. Declan’s Way is very much a journey back in time linking the ancient ecclesiastical centres of Ardmore in County Waterford and Cashel in County Tipperary. St. Declan brought Christianity to the Déise region of Waterford around 415AD shortly before the arrival of St. Patrick to Ireland. St. Patrick did not come further south than Cashel in his mission to bring the Christian story to the people of Ireland. St. Declan left Ardmore in Waterford and made the return journey to Cashel to meet St. Patrick on many occasions and so the pilgrim route was born. St. Declan’s Way remains faithful to the medieval pilgrimage and trading routes etched out on the landscape through the centuries. Following these ancient trails with Dr. Phil and Elaine will leave imprints that will last a lifetime. On our Camino, we quite literally walk in the steps of those who have gone before. When our own stories merge with the stories of old, it is then the magic happens. Let the journey begin! E; [email protected] T; +353 (0)87 9947921 W; www.waterfordcamino.com Day 1: Waterford – home of the Camino Aim to arrive at the Edmund Rice Centre, Barrack Street, Waterford (X91KH90) for 1pm. Cars will be parked here in safety for the duration of the week and your luggage will be transferred to the Tower Hotel. -

Charitable Tax Exemption

Charities granted tax exemption under s207 Taxes Consolidation Act (TCA) 1997 - 30 June 2021 Queries via Revenue's MyEnquiries facility to: Charities and Sports Exemption Unit or telephone 01 7383680 Chy No Charity Name Charity Address Taxation Officer Trinity College Dublin Financial Services Division 3 - 5 11 Trinity College Dublin College Green Dublin 2 21 National University Of Ireland 49 Merrion Sq Dublin 2 36 Association For Promoting Christian Knowledge Church Of Ireland House Church Avenue Rathmines Dublin 6 41 Saint Patrick's College Maynooth County Kildare 53 Saint Jarlath's College Trust Tuam Co Galway 54 Sunday School Society For Ireland Holy Trinity Church Church Ave Rathmines Dublin 6 61 Phibsboro Sunday And Daily Schools 23 Connaught St Phibsborough Dublin 7 62 Adelaide Blake Trust 66 Fitzwilliam Lane Dublin 2 63 Swords Old Borough School C/O Mr Richard Middleton Church Road Swords County Dublin 65 Waterford And Bishop Foy Endowed School Granore Grange Park Crescent Waterford 66 Governor Of Lifford Endowed Schools C/O Des West Secretary Carrickbrack House Convoy Co Donegal 68 Alexandra College Milltown Dublin 6 The Congregation Of The Holy Spirit Province Of 76 Ireland (The Province) Under The Protection Of The Temple Park Richmond Avenue South Dublin 6 Immaculate Heart Of Mary 79 Society Of Friends Paul Dooley Newtown School Waterford City 80 Mount Saint Josephs Abbey Mount Heaton Roscrea Co Tiobrad Aran 82 Crofton School Trust Ballycurry Ashford Co Wicklow 83 Kings Hospital Per The Bursar Ronald Wynne Kings Hospital Palmerstown