Origin of the Culdee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Antiphonary of Bangor and Its Musical Implications

The Antiphonary of Bangor and its Musical Implications by Helen Patterson A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Music University of Toronto © Copyright by Helen Patterson 2013 The Antiphonary of Bangor and its Musical Implications Helen Patterson Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Music University of Toronto 2013 Abstract This dissertation examines the hymns of the Antiphonary of Bangor (AB) (Antiphonarium Benchorense, Milan, Biblioteca Ambrosiana C. 5 inf.) and considers its musical implications in medieval Ireland. Neither an antiphonary in the true sense, with chants and verses for the Office, nor a book with the complete texts for the liturgy, the AB is a unique Irish manuscript. Dated from the late seventh-century, the AB is a collection of Latin hymns, prayers and texts attributed to the monastic community of Bangor in Northern Ireland. Given the scarcity of information pertaining to music in early Ireland, the AB is invaluable for its literary insights. Studied by liturgical, medieval, and Celtic scholars, and acknowledged as one of the few surviving sources of the Irish church, the manuscript reflects the influence of the wider Christian world. The hymns in particular show that this form of poetical expression was significant in early Christian Ireland and have made a contribution to the corpus of Latin literature. Prompted by an earlier hypothesis that the AB was a type of choirbook, the chapters move from these texts to consider the monastery of Bangor and the cultural context from which the manuscript emerges. As the Irish peregrini are known to have had an impact on the continent, and the AB was recovered in ii Bobbio, Italy, it is important to recognize the hymns not only in terms of monastic development, but what they reveal about music. -

A Way out Trilogy, and a Way Back

A w a y o u t t r i l o g y , a w a y o u t o f o u r r e l i g i o u s , p o l i t i c a l A n d p e r s o n a l p r e d i c a m e n t s , a n d a w a y b a c k , t a k i n g b a c k o u r r e l i g i o - n a t i o n a l h e r i t a g e – a l s o – o u r p e r s o n a l s p a c e H. D. K a I l I n Part I – t h e n a z a r e n e w a y o u t (Volume I) Beyond reach of Jerusalem, Rome, Geneva, stood the Orientalist (Volume II) Beyond the canonical gospels exists a Nazarene narrative gospel part I I – a m e r I c a ‘ s w a y o u t Three men with power: Washington, Jefferson, and Franklin Three women of valor: Tubman, Winnemuca, and Liliuokalani part I I I – m y o w n w a y o u t Gullible’s Travels: 50 years a Zionist, now seeking to make amends W e h a v e a s u r e , p r o p h e t I c W o r d B y I n s p I r a t I o n o f t h e L o r d ; A n d t h o ' a s s a I l e d o n e v ' r y h a n d , J e h o v a h ’ s W o r d s h a l l e v e r s t a n d . -

16.10 Celtic Music, Cornwall.Cdr

Who is the Workshop for? If you have ever wondered, n d World of th — what is it that makes Celtic Music so distinctive, spellbinding and enchanting? Sou e C — e what the aural equivalent is of the Book of Kells, with its extraordinary spiralic Celtic Knots? he Explore lt — what the early Celtic sacred music of St.Columba sounded like? T s then COME and SING YOUR HEART OUT on this weekend of UNFORGETTABLE MUSIC. the Uni que Sou ndscapes This workshop is appropriate for people with ALL levels of musical/vocal experience. Michael brings the message that everyone has a singer and a musician inside them and o f IRELAND, SCOTLAND & THE HEBRIDES looks forward to sharing his passion for singing Celtic Music with you. A BOOKSHOP OF RESOURCES will be for sale at the workshop, including Michael’s book of folk song arrangements,‘The Magic & Mysteries of Celtic Folk Songs’. Workshop Leader Michael Deason-Barrow Director of Tonalis Music Centre - runs inspirational courses all over the world connected to Choir Leading. He performed for a number of years in a folk/early music group called, ‘The Chanters of Taliesin’, regularly leads folk music in community choirs and specialises in creating distinctive arrangements of folk songs for choirs. This workshop is the culmination of 30 years research into Celtic Music, from: the mysteries of Irish folk singing (Sean Nós), to improvisatory Gaelic Psalm singing and the music of Scottish Travellers. Fees Early Bird Fees £75 (for booking by Aug. 1st) £80 (by Sept. 1st) £85 (thereafter) Couples, OAPs & Group Bookings (3+): £70/ £75/ £80 (see date deadlines above) from Saturday only fee: £45 (for booking by Aug. -

Exclusively Made Barn 14 Hip No. 1

Consigned by Tres Potrillos, Agent Barn Hip No. 14 Exclusively Made 1 Gone West Elusive Quality.................. Touch of Greatness Exclusive Quality .............. Glitterman Exclusively Made First Glimmer.................... Bay Filly; First Stand March 8, 2011 Danzig Furiously........................... Whirl Series Mad About Julie ............... (1999) Restless Restless Restless Julie.................... Witches Alibhai By EXCLUSIVE QUALITY (2003). Black-type winner of $92,600, Spectacular Bid S. [L] (GP, $45,000). Sire of 3 crops of racing age, 166 foals, 94 start- ers, 59 winners of 116 races and earning $2,727,453, including Sr. Quisqueyano ($319,950, Calder Derby (CRC, $150,350), etc.), Exclusive- ly Maria ($100,208, Cassidy S. (CRC, $60,000), etc.), Boy of Summer ($89,010, Journeyman Stud Sophomore Turf S.-R (TAM, $45,000)), black- type-placed Quality Lass ($158,055), Backstage Magic ($128,540). 1st dam MAD ABOUT JULIE, by Furiously. Winner at 3 and 4, $33,137. Dam of 4 other registered foals, 4 of racing age, 2 to race, 2 winners, including-- Jeongsang Party (f. by Exclusive Quality). Winner at 2, placed at 3, 2013 in Republic of Korea. 2nd dam Restless Julie, by Restless Restless. 2 wins at 2, $30,074, 2nd American Beauty S., etc. Dam of 11 other foals, 10 to race, all winners, including-- RESTING MOTEL (c. by Bates Motel). 8 wins at 2 and 3 in Mexico, cham- pion sprinter, Clasico Beduino, Handicap Cristobal Colon, Clasico Velo- cidad; winner at 4, $46,873, in N.A./U.S. PRESUMED INNOCENT (f. by Shuailaan). 7 wins, 3 to 6, $315,190, Jersey Lilly S. (HOU, $30,000), 2nd A.P. -

Christian Art, Architecture and Music

Christian Art, Architecture and Music LEARNING STRAND: HUMAN EXPERIENCE RELIGIOUS EDUCATION PROGRAMME FOR CATHOLIC SECONDARY SCHOOLS IN AOTEAROA NEW ZEALAND 12G TEACHER GUIDE THE LOGO The logo is an attempt to express Faith as an inward and outward journey. This faith journey takes us into our own hearts, into the heart of the world and into the heart of Christ who is God’s love revealed. In Christ, God transforms our lives. We can respond to his love for us by reaching out and loving one another. The circle represents our world. White, the colour of light, represents God. Red is for the suffering of Christ. Red also represents the Holy Spirit. Yellow represents the risen Christ. The direction of the lines is inwards except for the cross, which stretches outwards. Our lives are embedded in and dependent upon our environment (green and blue) and our cultures (patterns and textures). Mary, the Mother of Jesus Christ, is represented by the blue and white pattern. The blue also represents the Pacific… Annette Hanrahan RSCJ Cover photograph: Cathedral of the Blessed Sacrament, Christchurch / Diocese of Christchurch UNDERSTANDING FAITH YEAR 12 This book is the Teacher Guide to the following topic in the UNDERSTANDING FAITH series 12G CHRISTIAN ART, ARCHITECTURE AND MUSIC TEACHER GUIDE © Copyright 2007 by National Centre for Religious Studies No part of this document may be reproduced in any way, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means, without prior permission of the publishers. Imprimatur: † Colin D Campbell DD Bishop of Dunedin Conference Deputy for Religious Studies October 2007 Authorised by the New Zealand Catholic Bishops’ Conference Published by: National Centre for Religious Studies Catholic Centre P O Box 1937 Wellington New Zealand Printed by: Printlink 33-43 Jackson Street, Petone Private Bag, 39996 Wellington Mail Centre Lower Hutt 5045 Māori terms are italicised in the text. -

Ireland's Cultural Empire

Ireland’s Cultural Empire Ireland’s Cultural Empire: Contacts, Comparisons, Translations Edited by Giuliana Bendelli Ireland’s Cultural Empire: Contacts, Comparisons, Translations Edited by Giuliana Bendelli This book first published 2018 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2018 by Giuliana Bendelli and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-0924-9 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-0924-5 Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore contributed to the funding of this research project and its publication. TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface ....................................................................................................... vii Ireland: The Myth of a Colony Giuliana Bendelli Chapter One ................................................................................................. 1 Latin, Liturgy and Music in Early Mediaeval Ireland: From Columbanus to the Drummond Missal Guido Milanese Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 27 Oliver Goldsmith: An Irish Chinese Spectator in London Simona Cattaneo Chapter Three ........................................................................................... -

17.04 Celtic Music, FC.Cdr

Who is the Workshop for? If you have ever wondered, d World of — t what is it that makes Celtic Music so distinctive, spellbinding and enchanting? oun he — C what the aural equivalent is of the Book of Kells, with its extraordinary, spiralic Celtic Knots? e S e — Explore lt what the early Celtic sacred music of St.Columba sounded like? Th s then COME and SING YOUR HEART OUT on this weekend of UNFORGETTABLE MUSIC. the Unique Soundscapes This workshop is appropriate for people with ALL levels of musical/vocal experience. Michael brings the message that everyone has a singer and a musician inside them and looks forward to sharing his passion for singing Celtic Music with you. of IREL AND, SCO TLAND & T HE HEBRIDES A BOOKSHOP OF RESOURCES will be for sale at the workshop, including Michael’s new book of folk song arrangements,‘The Magic & Mysteries of Celtic Folk Songs’. in SONG Workshop Leader Michael Deason-Barrow - Director of Tonalis - runs inspirational courses all over the world connected to Holistic Singing, Choir Leading, Sacred Music and the Music of the Landscape. He performed in the folk/early music group, ‘The Chanters of Taliesin’ and today regularly leads folk music in community choirs and creates distinctive arrangements of folk songs for choirs. This workshop is the culmination of 30 years research into Celtic Music: from the mysteries of Irish folk singing and improvisatory Gaelic Psalm singing to the music of the Scottish Travellers. Fees & Times N.B. You can book for just the WEEKEND (8 - 9 April), or the WHOLE 3 DAY workshop. -

Celtic Chant | Grove Music

Celtic chant Ann Buckley https://doi.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.05266 Published in print: 20 January 2001 Published online: 2001 The liturgical chant sung by the Churches of the Celtic-speaking peoples of the Middle Ages before they conformed to the unitas catholica of the Roman Church. 1. Historical background. The liturgical practices observed in Christian worship by Celtic-speaking peoples were developed in monastic communities in Ireland, Scotland, Cumbria, Wales, Devon, Cornwall and Brittany. However, Celtic influence was also evident in certain areas controlled by the Anglo-Saxons, such as Northumbria, and extended to the Continent through the efforts of Irish missionaries during the 6th and 7th centuries. Chief among these last was St Columbanus (c543–615), founder of the monasteries of Luxeuil and Bobbio. His followers spread the customs of the Columbanian abbeys throughout centres in what are now France, Belgium, Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Italy and Spain. Several of the most important sources for the early Celtic liturgy are associated with the Columbanian foundations in Gaul. It is somewhat misleading to refer to ‘the Celtic Church’, since there was no single, uniform institution under central authority, and medieval Celtic-speaking Christians never considered themselves ‘Celtic’ in the sense of belonging to a national group, although an awareness of common purpose may be said to have existed for a brief period during the late 6th century and the early 7th. Nonetheless, the term serves as a useful way of classifying regional and cultural distinctiveness, by identifying what was essentially a network of monastic communities that shared a similar kind of structure and between whom there was regular, sometimes close, contact. -

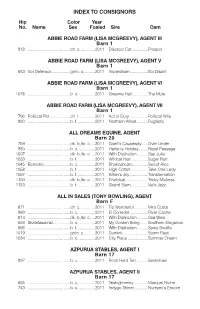

INDEX to CONSIGNORS Hip Color Year No

INDEX TO CONSIGNORS Hip Color Year No. Name Sex Foaled Sire Dam ABBIE ROAD FARM (LISA MCGREEVY), AGENT III Barn 1 818 ................................. ......ch. c. .............2011 Discreet Cat ...............Prosper ABBIE ROAD FARM (LISA MCGREEVY), AGENT V Barn 1 983 Soi Defensor .................gr/ro. c...........2011 Imperialism.................Soi Disant ABBIE ROAD FARM (LISA MCGREEVY), AGENT VI Barn 1 1078 ................................. ......b. c................2011 Graeme Hall...............The Mule ABBIE ROAD FARM (LISA MCGREEVY), AGENT VII Barn 1 796 Political Plot...................ch. f. ..............2011 Act of Duty .................Political Wife 820 ................................. ......b. f. ................2011 Northern Afleet...........Pugilistic ALL DREAMS EQUINE, AGENT Barn 20 759 ................................. ......dk. b./br. c. ...2011 Giant's Causeway......Over Under 880 ................................. ......b. c................2011 Harlan's Holiday.........Royal Passage 1007 ................................. ......dk. b./br. c. ...2011 With Distinction ..........Star Julia 1033 ................................. ......b. f. ................2011 Wildcat Heir................Sugar Run 1045 Benvolio.........................b. c................2011 Shakespeare..............Sweet Aloe 1058 ................................. ......b. f. ................2011 High Cotton................Take One Lady 1097 ................................. ......b. f. ................2011 Kitten's Joy.................Transformation -

O Czym Mowa? Czyli Krótko, Zwięźle I Na Temat O Terminologii I Dostępnej Literaturze Przedmiotu

O CZYM MOWA? CZYLI KRÓTKO, ZWIĘŹLE I NA TEMAT O TERMINOLOGII I DOSTĘPNEJ LITERATURZE PRZEDMIOTU. Podstawowym i zdaje się najważniejszym pytaniem jest: “Co dziś nazywamy muzyką irlandzką?”, a co za tym idzie: “Na ile dzisiejsza muzyka, prezentowana przez zespoły o dumnych nazwach “muzyki irlandzkiej” lub “muzyki celtyckiej” (w porywach do “irish band” tudzież “celtic group”), pokrywa się z autentycznym folklorem Irlandii?”. Zanim jednak rozpoczniemy rozważania na te tematy, zastanówmy się co rozumiemy pod podstawowymi pojęciami, jakimi są folk i folklor. Józef Burszta w swoim Słowniku etnologicznym1 zwraca uwagę, iż “Termin ten został wprowadzony w XIX wieku na oznaczenie zespołu elementów kulturowych ukształtowanych w obrębie “niższych” warstw społeczeństw narodowych określanych jako lud.” natomiast samo pojęcie folkloru wyjaśnia natomiast następująco: “Folklor, to odrębna i samodzielna część kultury symbolicznej, powszechnie, prawie bezrefleksyjnie właściwa konkretnym środowiskom (wiejskim, miejskim, zawodowym, towarzyskim itp.), mniejszym lub większym grupom społecznym, aż do całego społeczeństwa włącznie”2 Drugim badaczem, którego pozycję Słownik folkloru polskiego3 należy tu przytoczyć, jest Julian Krzyżanowski, którego definicja tego zjawiska brzmi następująco: “Folklor, z angielskiego folk-lore, znaczy odrębną kulturę umysłową ludu, wyraz lore określa bowiem kulturę jakiejś grupy społecznej, jej swoisty sposób mówienia, jej pieśni, opowiadania, wierzenia itp.” Krzyżanowski uwzględnia tu zwyczaje, obrzędy, wierzenia, przesądy obok zjawisk z zakresu kultury artystycznej, takich jak poezja obrzędowa, obrzędy i pieśni weselne i pogrzebowe, pieśni rekruckie i żołnierskie, wróżby i zaklęcia, przysłowia, zagadki, pieśni epickie, wiersze religijne, podania, mętowanie (formułki gier i zabaw dziecięcych), widowiska ludowe, pieśni liryczne, śpiewanki, śpiewniki i pieśni powszechne, folklor fabryczny i młynarski4. 1Józef Burszta, Folklor [w:] Słownik etnologiczny. Terminy ogólne, Warszawa-Poznań 1987 2 Józef Burszta, op. -

Josquin Des Prez, a History of Western

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations August 2013 Two Historiographical Studies in Musicology: Josquin Des Prez, a History of Western Music, and the Norton Anthology of Western Music: a Case Study; & in Search of Medieval Irish Chant and Liturgy: a Chronological Overview of the Secondary Literature Marianne Yvette Kordas University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Medieval History Commons, Music Commons, and the Other Education Commons Recommended Citation Kordas, Marianne Yvette, "Two Historiographical Studies in Musicology: Josquin Des Prez, a History of Western Music, and the Norton Anthology of Western Music: a Case Study; & in Search of Medieval Irish Chant and Liturgy: a Chronological Overview of the Secondary Literature" (2013). Theses and Dissertations. 234. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/234 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TWO HISTORIOGRAPHICAL STUDIES IN MUSICOLOGY: JOSQUIN DES PREZ, A HISTORY OF WESTERN MUSIC, AND THE NORTON ANTHOLOGY OF WESTERN MUSIC: A CASE STUDY & IN SEARCH OF MEDIEVAL IRISH CHANT AND LITURGY: A CHRONOLOGICAL OVERVIEW OF THE SECONDARY LITERATURE by Marianne Yvette Kordas A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Music at The University of Wisconsin—Milwaukee August 2013 ABSTRACT TWO HISTORIOGRAPHICAL STUDIES IN MUSICOLOGY: JOSQUIN DES PREZ, A HISTORY OF WESTERN MUSIC, AND THE NORTON ANTHOLOGY OF WESTERN MUSIC: A CASE STUDY & IN SEARCH OF MEDIEVAL IRISH CHANT AND LITURGY: A CHRONOLOGICAL OVERVIEW OF THE SECONDARY LITERATURE by Marianne Yvette Kordas The University of Wisconsin—Milwaukee, 2013 Under the Supervision of Professor Mitchell P. -

20.07 Celtic Choral, A5 Layout.Cdr

THE CELTIC CHOIR GIV E V OICE this Summer to the Mysteries and Magic of Music from IRE LAN D, SCOT LA N D & T H E H E B RID ES A Choral Festival Led by 2 in Parts Michael Weekend or Deason- Sun.pm - Tues. attendance Barrow welcomed from Weave Spellbinding Early Celtic Chant, Tapestries of Sound Mouth Music, Keening, into Enchanting & Sean Nós Irish Airs Choral Music to Magical Love Songs 1:30pm JULY 25th - 28th 2020 VENUE - THE FIELD CENTRE, nr Nailsworth, GLOS Enquiries: Tel. 01666-890460 / [email protected] www.tonalismusic.co.uk Celtic Soundscapes in Choral Music Celtic peoples often say that the world is made out of music. And what a different kind of music it is! (Even the Gaelic word for music, ‘ceol’, meaning ‘sounds like birds’, suggests this.) This ground-breaking CHORAL COURSE will vividly evoke for you CELTIC SOUNDSCAPES from the mountains and glens of Scotland, to the Hebridean Seascapes & the Celtic Otherworld of Ireland. Y’ ’ . Supernatural and spiritual dimensions abound, alongside mythic figures, shape-shifters and magical love songs. During these days you’ll have the chance to sing — The full array of Celtic Choral Music (many in New Arrangements) — Enchanting Love Songs (e.g. ‘She Moves through the Fair’) — Early Celtic Plainchant & Medieval Music from the Orkney’s from the songs of Columba to Deus Meus and the Hymn to St.Magnus. — the Ballads of Bards, Warriors and the Celtic Otherworld from ‘Cuchullain’s Lament for His Son’ and ‘Mo Ghile Meor’ to ‘The Fairies’ Love Song’.