Warfare and the Materialization of Daily Life at the Mississippian Common Field Site

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Many-Storied Place

A Many-storied Place Historic Resource Study Arkansas Post National Memorial, Arkansas Theodore Catton Principal Investigator Midwest Region National Park Service Omaha, Nebraska 2017 A Many-Storied Place Historic Resource Study Arkansas Post National Memorial, Arkansas Theodore Catton Principal Investigator 2017 Recommended: {){ Superintendent, Arkansas Post AihV'j Concurred: Associate Regional Director, Cultural Resources, Midwest Region Date Approved: Date Remove not the ancient landmark which thy fathers have set. Proverbs 22:28 Words spoken by Regional Director Elbert Cox Arkansas Post National Memorial dedication June 23, 1964 Table of Contents List of Figures vii Introduction 1 1 – Geography and the River 4 2 – The Site in Antiquity and Quapaw Ethnogenesis 38 3 – A French and Spanish Outpost in Colonial America 72 4 – Osotouy and the Changing Native World 115 5 – Arkansas Post from the Louisiana Purchase to the Trail of Tears 141 6 – The River Port from Arkansas Statehood to the Civil War 179 7 – The Village and Environs from Reconstruction to Recent Times 209 Conclusion 237 Appendices 241 1 – Cultural Resource Base Map: Eight exhibits from the Memorial Unit CLR (a) Pre-1673 / Pre-Contact Period Contributing Features (b) 1673-1803 / Colonial and Revolutionary Period Contributing Features (c) 1804-1855 / Settlement and Early Statehood Period Contributing Features (d) 1856-1865 / Civil War Period Contributing Features (e) 1866-1928 / Late 19th and Early 20th Century Period Contributing Features (f) 1929-1963 / Early 20th Century Period -

View / Open Gregory Oregon 0171N 12796.Pdf

CHUNKEY, CAHOKIA, AND INDIGENOUS CONFLICT RESOLUTION by ANNE GREGORY A THESIS Presented to the Conflict and Dispute Resolution Program and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science June 2020 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Anne Gregory Title: Chunkey, Cahokia, and Indigenous Conflict Resolution This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Science degree in the Conflict and Dispute Resolution Program by: Kirby Brown Chair Eric Girvan Member and Kate Mondloch Interim Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2020. ii © 2020 Anne Gregory This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs (United States) License. iii THESIS ABSTRACT Anne Gregory Master of Science Conflict and Dispute Resolution June 2020 Title: Chunkey, Cahokia, and Indigenous Conflicts Resolution Chunkey, a traditional Native American sport, was a form of conflict resolution. The popular game was one of several played for millennia throughout Native North America. Indigenous communities played ball games not only for the important culture- making of sport and recreation, but also as an act of peace-building. The densely populated urban center of Cahokia, as well as its agricultural suburbs and distant trade partners, were dedicated to chunkey. Chunkey is associated with the milieu surrounding the Pax Cahokiana (1050 AD-1200 AD), an era of reduced armed conflict during the height of Mississippian civilization (1000-1500 AD). The relational framework utilized in archaeology, combined with dynamics of conflict resolution, provides a basis to explain chunkey’s cultural impact. -

Caddo Archeology Journal, Volume 19. 2009

CCaddoaddo AArcheologyrcheology JJournalournal Volume 19 2009 CADDO ARCHEOLOGY JOURNAL Department of Sociology P.O. Box 13047, SFA Station Stephen F. Austin State University Nacogdoches, Texas 75962-3047 EDITORIAL BOARD TIMOTHY K. PERTTULA 10101 Woodhaven Dr. Austin, Texas 78753 e-mail: [email protected] GEORGE AVERY P.O. Box 13047, SFA Station Stephen F. Austin State University Nacogdoches, Texas 75962-3047 e-mail: [email protected] LIAISON WITH THE CADDO NATION OF OKLAHOMA ROBERT CAST Tribal Historic Preservation Offi cer Caddo Nation of Oklahoma P.O. Box 487 Binger, OK 73009 e-mail: [email protected] ISSN 1522-0427 Printed in the United States of America at Morgan Printing in Austin, Texas 2009 Table of Contents The Caddo and the Caddo Conference 1 Pete Gregory An Account of the Birth and Growth of Caddo Archeology, as Seen by Review of 50 Caddo Conferences, 1946-2008 3 Hester A. Davis and E. Mott Davis CADDO ARCHEOLOGY JOURNAL ◆ iii The Caddo and the Caddo Conference* Pete Gregory There was one lone Caddo at the early Caddo Conference held at the University of Oklahoma campus—Mrs. Vynola Beaver Newkumet—then there was a long gap. In 1973, the Chairman of the Caddo Nation, Melford Wil- liams, was the banquet speaker for the Conference, which was held in Natchitoches, Louisiana. A panel, consisting of Thompson Williams, Vynola Newkumet, Phil Newkumet, and Pete Gregory, was also part of that conference. Subsequent to 1973, Caddo representatives have not only been invited, but have attended the majority of the conferences. Caddo Nation chairpeople who have attended include Melford Williams, Mary Pat Francis, Hank Shemayme, Hubert Halfmoon, Elmo Clark, Vernon Hunter, and La Rue Martin Parker. -

Cultural Affiliation Statement for Buffalo National River

CULTURAL AFFILIATION STATEMENT BUFFALO NATIONAL RIVER, ARKANSAS Final Report Prepared by María Nieves Zedeño Nicholas Laluk Prepared for National Park Service Midwest Region Under Contract Agreement CA 1248-00-02 Task Agreement J6068050087 UAZ-176 Bureau of Applied Research In Anthropology The University of Arizona, Tucson AZ 85711 June 1, 2008 Table of Contents and Figures Summary of Findings...........................................................................................................2 Chapter One: Study Overview.............................................................................................5 Chapter Two: Cultural History of Buffalo National River ................................................15 Chapter Three: Protohistoric Ethnic Groups......................................................................41 Chapter Four: The Aboriginal Group ................................................................................64 Chapter Five: Emigrant Tribes...........................................................................................93 References Cited ..............................................................................................................109 Selected Annotations .......................................................................................................137 Figure 1. Buffalo National River, Arkansas ........................................................................6 Figure 2. Sixteenth Century Polities and Ethnic Groups (after Sabo 2001) ......................47 -

APR 2 7 200I National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form

NPS Form 10^900-b OMB No. 1024-<X (Revised March 1992) United Skates Department of the Interior iatlonal Park Service APR 2 7 200I National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form Is used for documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See Instructions in How to Complete t MuMple Property Documentation Form (National Register Bulletin 168). Complete each Item by entering the requested information. For additional space, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all Items. _X_ New Submission __ Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Listing Native American Rock Art Sites of Illinois B. Associated Historic Contexts_______________________________ (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) Native American Rock Art of Illinois (7000 B.C. - ca. A. D. 1835) C. Form Prepared by name/title Mark J. Wagner, Staff Archaeologist organization Center for Archaeological Investigations dat0 5/15/2000 Southern Illinois University street & number Mailcode 4527 telephone (618) 453-5035 city or town Carbondale state IL zip code 62901-4527 D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth In 36 CFR Part 60 and the Secretary of the Interior's Standards and Guidelines for Archeology and Historic Preservation. -

2016 Athens, Georgia

SOUTHEASTERN ARCHAEOLOGICAL CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS & ABSTRACTS OF THE 73RD ANNUAL MEETING OCTOBER 26-29, 2016 ATHENS, GEORGIA BULLETIN 59 2016 BULLETIN 59 2016 PROCEEDINGS & ABSTRACTS OF THE 73RD ANNUAL MEETING OCTOBER 26-29, 2016 THE CLASSIC CENTER ATHENS, GEORGIA Meeting Organizer: Edited by: Hosted by: Cover: © Southeastern Archaeological Conference 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS THE CLASSIC CENTER FLOOR PLAN……………………………………………………...……………………..…... PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS…………………………………………………………………….…..……. LIST OF DONORS……………………………………………………………………………………………….…..……. SPECIAL THANKS………………………………………………………………………………………….….....……….. SEAC AT A GLANCE……………………………………………………………………………………….……….....…. GENERAL INFORMATION & SPECIAL EVENTS SCHEDULE…………………….……………………..…………... PROGRAM WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 26…………………………………………………………………………..……. THURSDAY, OCTOBER 27……………………………………………………………………………...…...13 FRIDAY, OCTOBER 28TH……………………………………………………………….……………....…..21 SATURDAY, OCTOBER 29TH…………………………………………………………….…………....…...28 STUDENT PAPER COMPETITION ENTRIES…………………………………………………………………..………. ABSTRACTS OF SYMPOSIA AND PANELS……………………………………………………………..…………….. ABSTRACTS OF WORKSHOPS…………………………………………………………………………...…………….. ABSTRACTS OF SEAC STUDENT AFFAIRS LUNCHEON……………………………………………..…..……….. SEAC LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT AWARDS FOR 2016…………………….……………….…….…………………. Southeastern Archaeological Conference Bulletin 59, 2016 ConferenceRooms CLASSIC CENTERFLOOR PLAN 6 73rd Annual Meeting, Athens, Georgia EVENT LOCATIONS Baldwin Hall Baldwin Hall 7 Southeastern Archaeological Conference Bulletin -

Doi 10136

<ennewick Man--Ames chapter http://www.cr.nps.gov/aad/design/'kennewick/AMES.HTM IARCHEOLOG¥ _z ETHNOGRAPHY PROGRAM Peoples&gultures Kennewick Man Chapter 2 CulturalAffiliationReport Section1 Review of the Archaeological Data Kenneth A_ Ames Acknowledgments Alexander GalE,Stephanie Butler and ,Ion Daehnke, all of Introduction Portland State University, gave me invaluable assistance in the production of this document. They assisted me with :: scopeofWorkand library research, the bibliography, data bases and so on and Methodology on. However, neither they, nor any of the people with whom :: ,_:,rganizatiofonthis I consulted on this work (see list below) bear any Report responsibilities for errors, ideas, or conclusions drawn here. -he _',:,Ghem ,',ColumL_ia) That responsibility is solely mine. Plat _aU Background =s-:uesProodem Introd uction "EartierGroup" This report is part of the cultural affiliation study, under NAGPRA, of the Kennewick human remains. The ._.r,:haeologvortheEarly circumstances of the finding of those remains, and the Modern Period: The Other resulting controversies, are well enough known not to EndoftheSequence require rehearsal here. The present work reviews the extant Reviewd the archaeological record for the Southern Columbia Plateau Archaeological Record: (sensu Ames et al. 1998) (Figure 1). Continuities, Discontinuities an:Ga s Scope of Work and Methodology Cotlclusions The framework for this study is set out in the scope of work Bibliography (SOW) dated December 9, 1999. It is important to be quite explicit about what the scope of work and the parameters of LiaofFigures this study are. Therefore, in summarizing the SoW, I either closely paraphrase its wording, or quote extensively. The project's scope of work included: • "Identify an "earlier group" with which the Kennewick human remains could be associated. -

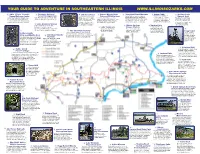

Hardin County Area Map.Pdf

YOUR GUIDE TO ADVENTURE IN SOUTHEASTERN ILLINOIS WWW.ILLINOISOZARKS.COM 1 Ohio River Scenic 4 Shawnee National 3 Old Stone Face 6 Sahara Woods State 7 Stonefort Depot Museum 11 Camp Cadiz 15 Golden Circle This former coal mining area Byway Welcome Center Forest Headquarters A ½ mile moderately strenuous Fish and Wildlife Area Built in 1890, this former railroad depot Natural Arch is now a 2,300 acre state park On the corner in downtown Equality. View Main office for the national forest with visitor trail takes you to scenic vistas This former coal mining area is now a is a step back in time with old signs from This unique rock arch forms a managed for hunting and fishing. their extensive collection of artifacts from information, displays and souvenirs for sale. and one of the finest and natural 2,300 acre state park managed for hunting railroad companies and former businesses, natural amphitheater that was Plans are being developed for the salt well industry while taking advantage stone face rock formations. and fishing. Plans are being developed tools and machines from the heyday of the secret meeting place of a off-road vehicle recreation trails. of indoor restrooms and visitor’s information. Continue on the Crest Trail to for off-road vehicle recreation trails. railroads and telegraphs are on display. group of southern sympathizers, the Tecumseh Statue at Glen the Knights of the Golden 42 Lake Glendale Stables O Jones Lake 3 miles away. Circle, during the Civil War. Saddle up and enjoy an unforgettable 40 Hidden Springs 33 Burden Falls horseback ride no matter what your 20 Lake Tecumseh Ranger Station During wet weather, an intermittent stream spills experience level. -

62Nd Annual Midwest Archaeological Conference October 4–6, 2018 No T R E Dame Conference Center Mc Kenna Hall

62nd Annual Midwest Archaeological Conference October 4–6, 2018 No t r e Dame Conference Center Mc Kenna Hall Parking ndsp.nd.edu/ parking- and- trafǢc/visitor-guest-parking Visitor parking is available at the following locations: • Morris Inn (valet parking for $10 per day for guests of the hotel, rest aurants, and conference participants. Conference attendees should tell t he valet they are here for t he conference.) • Visitor Lot (paid parking) • Joyce & Compt on Lot s (paid parking) During regular business hours (Monday–Friday, 7a.m.–4p.m.), visitors using paid parking must purchase a permit at a pay st at ion (red arrows on map, credit cards only). The permit must be displayed face up on the driver’s side of the vehicle’s dashboard, so it is visible to parking enforcement staff. Parking is free after working hours and on weekends. Rates range from free (less than 1 hour) to $8 (4 hours or more). Campus Shut t les 2 3 Mc Kenna Hal l Fl oor Pl an Registration Open House Mai n Level Mc Kenna Hall Lobby and Recept ion Thursday, 12 a.m.–5 p.m. Department of Anthropology Friday, 8 a.m.–5 p.m. Saturday, 8 a.m.–1 p.m. 2nd Floor of Corbett Family Hall Informat ion about the campus and its Thursday, 6–8 p.m. amenities is available from any of t he Corbett Family Hall is on the east side of personnel at the desk. Notre Dame Stadium. The second floor houses t he Department of Anthropology, including facilities for archaeology, Book and Vendor Room archaeometry, human osteology, and Mc Kenna Hall 112–114 bioanthropology. -

Monks Mound—Center of the Universe? by John Mcclarey

GUEST ESSAY Monks Mound—Center of the universe? By John McClarey hyperbole or a facsimile? I think the case can be made that Monks Mound and the entire Alayout of this ancient metropolis in the H American Bottom near East St. Louis was a facsimile or model of Cahokia’s place in the cosmos, similar to the Black Hills as a “mirror or heaven” or the heart of all that is.” These are good metaphors to describe Cahokia’s center in the three-layer cake concept of the universe—the Underworld, the Earth, and the Sky. Cahokia by the 12th century B.C.E., was the place for people to connect with the spirits of this sacred sphere. In this article I will identify the sacred elements that made this place special to local and non-local populations and the role of the Birdman chiefs, priests, and shamans to interpret this unique place as a center in a larger world. Additionally, I identify the similarities of Cahokia as a a sacred place to other societies at different times and places. My fascination with Cahokia Mounds developed over a period of time with many visits from the early 1970s to the present. Briefly, Cahokia was the largest America city north of Mexico before the coming of the Europeans in the 15th cen- tury. It is believed that Cahokia was a political, religious, and economic center for perhaps as many as 500,000 Indians in the Mississippi Valley. It was a planned city with everything the world and in all religions, but the focus here is on the laid out on the cardinal points on the compass, Monks Cahokia Mounds in southern Illinois and cross culture Mound, the largest mound at the center, served as the official comparisons, Cahokia’s unique story includes the cruciform residence of the Great Sun god or Birdman deity. -

The Future of the Past: Science in Archaeology Illinois Antiquity Vol

The Future of the Past: Science in Archaeology Illinois Antiquity Vol. 50, No. 3 September 2015 REFERENCES AND SUGGESTED READINGS ARCHAEOLOGY AND ECOLOGY: BRIDGING THE SCIENCES THROUGH INTERDISCIPLINARY RESEARCH By Carol E. Colaninno LiDAR ILLUMINATED By Michael Farkas IDENTIFYING BLACK DRINK CEREMONIALISM AT CAHOKIA: CHEMICAL RESIDUE ANALYSIS By Thomas E. Emerson and Timothy R. Pauketat SOURCING NATIVE AMERICAN CERAMICS FROM WESTERN ILLINOIS By Julie Zimmermann Holt, Andrew J. Upton, and Steven A. Hanlin Conrad, Lawrence A. 1989 The Southeastern Ceremonial Complex on the Northern Middle Mississippian Frontier: Late Prehistoric Politico-religious Systems in the Central Illinois River Valley. In The Southeastern Ceremonial Complex: Artifacts and Analysis, edited by P. Galloway, pp. 93-113. University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln. 1991 The Middle Mississippian Cultures of the Central Illinois Valley. In Cahokia and the Hinterlands: Middle Mississippian Cultures of the Midwest, edited by T. E. Emerson and R. B. Lewis, pp. 119-156. University of Illinois Press, Urbana. Dye, David H. 2004 Art, Ritual, and Chiefly Warfare in the Mississippian World. In Hero, Hawk, and Open Hand: American Indian Art of the Ancient Midwest and South, edited by R. F. Townsend, pp. 191-205. The Art Institute, Chicago. Fie, Shannon M. 2006 Visiting in the Interaction Sphere: Ceramic Exchange and Interaction in the Lower Illinois Valley. In Recreating Hopewell, edited by D. K. Charles and J. E. Buikstra, pp. 427-45. University Press of Florida, Gainesville. 2008 Middle Woodland Ceramic Exchange in the Lower Illinois Valley. Midcontinental Journal of Archaeology 33:5-40. Fowles, Severin M., Leah Minc, Samuel Duwe and David V. -

Own and Be Owned Archaeological Approaches to the Concept of Possession

Own and be owned Archaeological approaches to the concept of possession P AG – Postdoctoral Archaeological Group Alison Klevnäs & Charlotte Hedenstierna-Jonson (Eds) Stockholm Studies in Archaeology 62, 2015 Own and be owned Archaeological approaches to the concept of possession © 2015 by PAG – Postdoctoral Archaeological Group, and the authors Department of Archaeology and Classical Studies Stockholm University SE-106 91 Stockholm www.archaeology.su.se Editors: Alison Klevnäs & Charlotte Hedenstierna-Jonson English revision: Kristin Bornholdt Collins Cover and typography: Anna Röst, Karneol form & kommunikation Printed by Publit, Stockholm, Sweden 2015 ISSN 0349-4128 ISBN 978-91-637-8212-1 Contents Preface vii Alison Klevnäs & Charlotte Hedenstierna-Jonson Introduction: the nature of belongings 1 Alison Klevnäs Things of quality: possessions and animated objects in the Scandinavian Viking Age 23 Nanouschka Myrberg Burström The skin I live in. The materiality of body imagery 49 Fredrik Fahlander To own and be owned: the warriors of Birka’s garrison 73 Charlotte Hedenstierna-Jonson The propriety of decorative luxury possessions. Reflections on the occurrence of kalathiskos dancers and pyrrhic dancers in Roman visual culture 93 Julia Habetzeder Hijacked by the Bronze Age discourse? A discussion of rock art and ownership 109 Per Nilsson Capturing images: knowledge, ownership and the materiality of cave art 133 Magnus Ljunge Give and take: grave goods and grave robbery in the early middle ages 157 Alison Klevnäs Possession through deposition: the 'ownership' of coins in contemporary British coin-trees 189 Ceri Houlbrook Possession, property or ownership? 215 Chris Gosden About the authors 222 Things of quality: possessions and animated objects in the Scandinavian Viking Age Nanouschka M.