Anderson, Peter. “The Architecture of Interpretation.”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1960 National Gold Medal Exhibition of the Building Arts

EtSm „ NA 2340 A7 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from LYRASIS Members and Sloan Foundation http://archive.org/details/nationalgoldOOarch The Architectural League of Yew York 1960 National Gold Medal Exhibition of the Building Arts ichievement in the Building Arts : sponsored by: The Architectural League of New York in collaboration with: The American Craftsmen's Council held at: The Museum of Contemporary Crafts 29 West 53rd Street, New York 19, N.Y. February 25 through May 15, i960 circulated by The American Federation of Arts September i960 through September 1962 © iy6o by The Architectural League of New York. Printed by Clarke & Way, Inc., in New York. The Architectural League of New York, a national organization, was founded in 1881 "to quicken and encourage the development of the art of architecture, the arts and crafts, and to unite in fellowship the practitioners of these arts and crafts, to the end that ever-improving leadership may be developed for the nation's service." Since then it has held sixtv notable National Gold Medal Exhibitions that have symbolized achievement in the building arts. The creative work of designers throughout the country has been shown and the high qual- ity of their work, together with the unique character of The League's membership, composed of architects, engineers, muralists, sculptors, landscape architects, interior designers, craftsmen and other practi- tioners of the building arts, have made these exhibitions events of outstanding importance. The League is privileged to collaborate on The i960 National Gold Medal Exhibition of The Building Arts with The American Crafts- men's Council, the only non-profit national organization working for the benefit of the handcrafts through exhibitions, conferences, pro- duction and marketing, education and research, publications and information services. -

The Meter Greeters

Journal of Applied Communications Volume 59 Issue 2 Article 3 The Meter Greeters C. Hamilton Kenney Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/jac This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Kenney, C. Hamilton (1976) "The Meter Greeters," Journal of Applied Communications: Vol. 59: Iss. 2. https://doi.org/10.4148/1051-0834.1951 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Applied Communications by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Meter Greeters Abstract The United States and Canada became meter greeters away back in the 1800's. The U.S. Congress passed an act in 1866 legalizing the metric system for weights and measures use, and metric units were on the law books of the Dominion of Canada in 1875. This article is available in Journal of Applied Communications: https://newprairiepress.org/jac/vol59/iss2/3 Kenney: The Meter Greeters The Meter Greeters C. Hamilton Kenney The United States and Canada became meter greeters away back in the 1800's. The U.S. Congress passed an act in 1866 legalizing the metric system for weights and measures use, and metric units were on the law books of the Dominion of Canada in 1875. The U.S. A. was a signatory to the Treaty of the Meter l signed in Paris, France. in 1875, establishing the metric system as an international measurement system, but Canada did not become a signatory nation until 1907. -

In the Name of Krishna: the Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town

In the Name of Krishna: The Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Sugata Ray IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Frederick M. Asher, Advisor April 2012 © Sugata Ray 2012 Acknowledgements They say writing a dissertation is a lonely and arduous task. But, I am fortunate to have found friends, colleagues, and mentors who have inspired me to make this laborious task far from arduous. It was Frederick M. Asher, my advisor, who inspired me to turn to places where art historians do not usually venture. The temple city of Khajuraho is not just the exquisite 11th-century temples at the site. Rather, the 11th-century temples are part of a larger visuality that extends to contemporary civic monuments in the city center, Rick suggested in the first class that I took with him. I learnt to move across time and space. To understand modern Vrindavan, one would have to look at its Mughal past; to understand temple architecture, one would have to look for rebellions in the colonial archive. Catherine B. Asher gave me the gift of the Mughal world – a world that I only barely knew before I met her. Today, I speak of the Islamicate world of colonial Vrindavan. Cathy walked me through Mughal mosques, tombs, and gardens on many cold wintry days in Minneapolis and on a hot summer day in Sasaram, Bihar. The Islamicate Krishna in my dissertation thus came into being. -

Renzo Piano Designs a Reverent Addition to Louis Kahn's Kimbell

SEEMING INEVITABILITY: renzo piano designs a reverent addition to louis kahn’s kimbell 6 spring INEVITABILITY: Lef: Aerial view from northwest. Above: Piano Pavilion from east, 2014. Photos: Michel Denancé. by ronnie self Louis Kahn’s and Renzo Piano’s buildings for the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth are mature projects realized by septuagenarian architects. They show a certain wis- dom that may come with age. As a practitioner, Louis Kahn is generally considered a late bloomer. His most respected works came relative- ly late in his career, and the Kimbell, which opened a year and a half before his death, is among his very best. Many of Kahn’s insights came through reflection in parallel to practice, and his pursuits to reconcile modern architec- ture with traditions of the past were realized within his own, individual designs. spring 7 Piano (along with Richard Rogers and Gianfranco Franchini) won the competition for the Centre Pompidou in Paris as a young architect piano’s main task was to respond appropriately only in his mid-30s. Piano sees himself as a “builder” and his insights come largely through experience. Aside from the more famboyant Cen- to kahn’s building, which he achieved through tre in the French capital, Piano was entrusted relatively early in his career with highly sensitive projects in such places as Malta, Rhodes, alignments in plan and elevation ... and Pompeii. He made studies for interventions to Palladio’s basilica in Vicenza. More recently he has been called upon to design additions to modern architectural monuments such as Marcel Breuer’s Whitney Mu- seum of American Art in New York and Le Corbusier’s chapel of Notre Dame du Haut in Ronchamp. -

All Things Country with Rowena Playlist for September 5, 2020

All Things Country Playlist September 5, 2020 Mel Street Walk Softly On The Bridges Greatest Hits GRT Connie Moore Just Love Me Twice As Hard Tomorrow 45rpm single Spur Don Williams She Never Knew Me Harmony Dot LP The Wilders Honky Tonk Habit Throw Down Rural Grit George Morgan I'll Furnish The Shoulder You Cry On Candy Kisses Bear Family Gretchen Wilson Red Neck Woman Here For The Party Epic Tanya Tucker The Day My Heart Goes Still While I'm Livin' Fantasy Chris Scruggs Sober Up And Think Honky Tonkin' Lifestyle self Eddie Rabbitt Drivin' My Life Away Horizon Elektra Mary Battiata & Little Pink Things You Say And Don't Say The Heart, Regardless self Merle Haggard Man From Another Time Chill Factor Epic Buddy Jewell Dyess Arkansas Times Like These Sony Carol Johnson According To Law Meet The Pearls: Juke Box Pearls Bear Family Curtis Wright I Can't Stand To Watch My Old Flame Burn Curtis Wright Liberty Patty Loveless Daniel Prayed Mountain Soul Epic George Jones Old Brush Arbors Walk Through This World With Me: Bear Family Complete Musicor Recordings, Vol. 1 Hoppers Yes I Am Power Spring Hill Music Rani Arbo & Daisy Mayhem Joy Comes Back Big Old Life Signature Sounds Aussie Bush Band Aussie Bbq Bush Songs From The Australian Outback Collectables Shavonne Make Me One Promise single self Ricky Van Shelton Living Proof Loving Proof Columbia Waylon Jennings & Willie Nelson Just To Satisfy You Waylon & Company RCA Victor LP Amber Digby A Man I Hardly Know Music From The Honky Tonks Heart Of Texas Jerry Reed She Got The Gold Mine (I Got The Shaft) The Essential Jerry Reed Sony Legacy Tim Wilson I Married A Woman Who Talks Like Jerry Reed Tuned Up Southern Tracks Dale Watson A Couple Of Beers Ago The Essential Dale Watson Cjub Entertainment Dale Watson No Fussin', No Cussin', Mama's Hungry Preachin' To The Choir: Live At The Continental Song City Eyes, Another Day Another Dollar, Call It Borderline A Night John England & The Western Swingers Deep Water Swinging Broadway self Asleep At The Wheel, feat. -

US Marine Corps Base Hawaii, Kaneohe Bay

NAVAL AIR STATION KANEOHE, ADMINISTRATION AND HABS Hl-311-P OPERATIONS BUILDING HABS H/-311-P (U.S. Marine Corps Base Hawaii, Kaneohe Bay, Facility 215) E Street between 3rd and 4th streets Kq1n,@0t1e Honolulu County Hawaii PHOTOGRAPHS WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA FIELD RECORDS HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDINGS SURVEY National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior 1849 C Street NW Washington, DC 20240-0001 HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDINGS SURVEY U.S. NAVAL AIR STATION KANEOHE, OAHU, ADMINISTRATION AND OPERATIONS BUILDING (U.S. Marine Corps Base Hawaii, Kaneohe Bay, Facility 215) HABS No. Hl-311-P Location: Honolulu County, Hawaii U.S.G.S. Mokapu Point quadrangle, 1998 7.5 Minute Series (Topographic) (Scale - 1 :24,000) NAD83 datum. Universal Transverse Mercator Coordinates: 04.628510.2371690. Lat./ Long. Coordinates: 21 °26'35.05" N 157°45'35.45" W Date of Construction: 1941 Designer: Albert Kahn, Inc., Detroit, Michigan Builder: Contractors, Pacific Naval Air Bases Owner: U.S. Marine Corps Present Use: Offices Significance: Facility 215, Administration and Operations Building, is significant for its association with U.S. Naval Air Station (NAS) Kaneohe and its role before the onset of World War II (WWII) in the Pacific. It was one of the primary buildings during the establishment of the U.S. Naval Air Station Kaneohe and headquarters for the station coll1111ander. The building contained the offices for numerous important administrative and coll1111unication functions of the station. The ca. 1939 building is also significant as a part of the original design of the station. In addition, Facility 215 at Kaneohe, along with forty-three other facilities there, is significant because it embodies distinctive characteristics of building types in this period that were designed by the notable architectural firm of Albert Kahn, Inc. -

ANNE TYNG: INHABITING GEOMETRY April 15 – June 18, 2011 GRAHAM FOUNDATION

ANNE TYNG: INHABITING GEOMETRY April 15 – June 18, 2011 GRAHAM FOUNDATION Anne Tyng, A Life Chronology By: Ingrid Schaffner, Senior Curator, Institute of Contemporary Art Philadelphia & William Whitaker, Curator and Collections Manager, The Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania All quotes: Anne Tyng. 1920 Bauer; classmates include Lawrence Halprin, Philip July 14: born in Jiangxi, China, to Ethel and Walworth Johnson, Eileen Pei, I.M. Pei, and William Wurster. Tyng, American Episcopal Missionaries. The fourth of five children, Tyng lives in China until 1934 with periodic furloughs in the United States. 1944 Graduates Harvard University, MA Architecture. In New York, works briefly in the offices of: Konrad Wachsmann; 1937 Van Doren, Nowland, and Schladermundt; Knoll Graduates St. Mary‘s School, Peekskill, New York. Returns Associates. to China for a family visit; continues to travel with her sister around the world via South Asia and Europe. 1945 Moves to Philadelphia to live with parents (having left as refugees of the Japanese invasion in 1939, they return to 1938 China in 1946). Employed by Stonorov and Kahn. The only Enrolls in Radcliffe College, majoring in fine arts. woman in an office of six, Tyng is involved in residential and city planning projects. 1941 1947 Takes classes at the Smith Graduate School of Architecture Joins Louis I. Kahn in his independent practice; initial and Landscape Architecture (a.k.a The Cambridge School), projects include the Weiss House (1947-50) and Genel the first women‘s school to offer architectural studies in House (1948-51), as well as the Radbill Building and the United States. -

History of Twentieth Century Architecture: Richards Medical Labs by Louis Kahn

History of Twentieth Century Architecture: Richards Medical Labs by Louis Kahn Louis I. Kahn (b. Kuressaare, Saaremaa, Estonia 1901; d. New York, NY, United States of America 1974) Louis Kahn completed his Bachelor of Architecture in 1924 at University of Pennsylvania. Former professor of Yale University and University of Pennsylvania. His most famous designs: Yale Art Gallery, Salk Institute, Fisher House, Jatiyo Sangshad Bhaban, Exeter Library and Kimbell Art Museum. Fellow in the American Institute of Architects and member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Awarded with the Frank P. Brown Medal in 1964, the AIA Gold Medal and Royal Gold Medal by the RIBA in 1972. In 1957, Kahn left University of Yale to teach at University of Pennsylvania where he also received a commission to design a new building for the campus, the Alfred Newton Richards Medical Research Laboratories Buildings. In his first design, the service towers would act as columns for the laboratories’ floors, but he changed it, following the advice of his engineers who suggested him to position the columns to the third points of the buildings. (Vincent Scully, 1962, p. 28) A successful partnership between Kahn and August Komendant, a structural engineer, started during this project. Komendant was a pioneer in using precast and pre- Nelly Chang, 2010 The redbrick facade seemed to be a stressed concrete to build bridges in Germany. The use sensible choice for Richards Labs as it of his expertise can be easily seen in Richards Labs, was surrounded by the 19th century Xavier de Jauréguiberry, 2011 Xavier de Jauréguiberry, buildings of the University campus. -

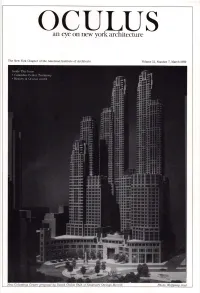

An Eye on New York Architecture

OCULUS an eye on new york architecture The New York Chapter of the American Institute of Architects Volume 51, Number 7, March 1989 ew Co lumbus Center proposal by David Childs FAIA of Skidmore Owings Merrill. 2 YC/AIA OC LUS OCULUS COMING CHAPTER EVENTS Volume 51, Number 7, March 1989 Oculus Tuesday, March 7. The Associates Tuesday, March 21 is Architects Lobby Acting Editor: Marian Page Committee is sponsoring a discussion on Day in Albany. The Chapter is providing Art Director: Abigail Sturges Typesetting: Steintype, Inc. Gordan Matta-Clark Trained as an bus service, which will leave the Urban Printer: The Nugent Organization architect, son of the surrealist Matta, Center at 7 am. To reserve a seat: Photographer: Stan Ri es Matta-Clark was at the center of the 838-9670. avant-garde at the end of the '60s and The New York Chapter of the American Institute of Architects into the '70s. Art Historian Robert Tuesday, March 28. The Chapter is 457 Madison Avenue Pincus-Witten will be moderator of the co-sponsoring with the Italian Marble New York , New York 10022 evening. 6 pm. The Urban Center. Center a seminar on "Stone for Building 212-838-9670 838-9670. Exteriors: Designing, Specifying and Executive Committee 1988-89 Installing." 5:30-7:30 pm. The Urban Martin D. Raab FAIA, President Tuesday, March 14. The Art and Center. 838-9670. Denis G. Kuhn AIA, First Vice President Architecture and the Architects in David Castro-Blanco FAIA, Vice President Education Committees are co Tuesday, March 28. The Professional Douglas Korves AIA, Vice President Stephen P. -

Harriet Pattison Oral History Transcript

The Cultural Landscape Foundation® Pioneers of American Landscape Design® ___________________________________ HARRIET PATTISON ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW TRANSCRIPT ___________________________________ Interviews Conducted June 17-19, 2015 By Charles A. Birnbaum, FASLA, FAAR Gina M. Angelone, Director © 2016 The Cultural Landscape Foundation, all rights reserved. May not be used or reproduced without permission. The Cultural Landscape Foundation® Pioneers of American Landscape Design® Oral History Series: Harriet Pattison Interview Transcript Table of Contents PRELUDE ........................................................................................................................................................................ 4 BIOGRAPHY ................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Childhood................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Growing Up in Chicago .......................................................................................................................................... 4 City Full of Wonders .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Francis Parker School ........................................................................................................................................ -

Calendrical Calculations: the Millennium Edition Edward M

Errata and Notes for Calendrical Calculations: The Millennium Edition Edward M. Reingold and Nachum Dershowitz Cambridge University Press, 2001 4:45pm, December 7, 2006 Do I contradict myself ? Very well then I contradict myself. (I am large, I contain multitudes.) —Walt Whitman: Song of Myself All those complaints that they mutter about. are on account of many places I have corrected. The Creator knows that in most cases I was misled by following. others whom I will spare the embarrassment of mention. But even were I at fault, I do not claim that I reached my ultimate perfection from the outset, nor that I never erred. Just the opposite, I always retract anything the contrary of which becomes clear to me, whether in my writings or my nature. —Maimonides: Letter to his student Joseph ben Yehuda (circa 1190), Iggerot HaRambam, I. Shilat, Maaliyot, Maaleh Adumim, 1987, volume 1, page 295 [in Judeo-Arabic] If you find errors not given below or can suggest improvements to the book, please send us the details (email to [email protected] or hard copy to Edward M. Reingold, Department of Computer Science, Illinois Institute of Technology, 10 West 31st Street, Suite 236, Chicago, IL 60616-3729 U.S.A.). If you have occasion to refer to errors below in corresponding with the authors, please refer to the item by page and line numbers in the book, not by item number. Unless otherwise indicated, line counts used in describing the errata are positive counting down from the first line of text on the page, excluding the header, and negative counting up from the last line of text on the page including footnote lines. -

Water Heater Formulas and Terminology

More resources http://waterheatertimer.org/9-ways-to-save-with-water-heater.html http://waterheatertimer.org/Figure-Volts-Amps-Watts-for-water-heater.html http://waterheatertimer.org/pdf/Fundamentals-of-water-heating.pdf FORMULAS & FACTS BTU (British Thermal Unit) is the heat required to raise 1 pound of water 1°F 1 BTU = 252 cal = 0.252 kcal 1 cal = 4.187 Joules BTU X 1.055 = Kilo Joules BTU divided by 3,413 = Kilowatt (1 KW) FAHRENHEIT CENTIGRADE 32 0 41 5 To convert from Fahrenheit to Celsius: 60.8 16 (°F – 32) x 5/9 or .556 = °C. 120.2 49 140 60 180 82 212 100 One gallon of 120°F (49°C) water BTU output (Electric) = weighs approximately 8.25 pounds. BTU Input (Not exactly true due Pounds x .45359 = Kilogram to minimal flange heat loss.) Gallons x 3.7854 = Liters Capacity of a % of hot water = cylindrical tank (Mixed Water Temp. – Cold Water – 1⁄ 2 diameter (in inches) Temp.) divided by (Hot Water Temp. x 3.146 x length. (in inches) – Cold Water Temp.) Divide by 231 for gallons. % thermal efficiency = Doubling the diameter (GPH recovery X 8.25 X temp. rise X of a pipe will increase its flow 1.0) divided by BTU/H Input capacity (approximately) 5.3 times. BTU output (Gas) = GPH recovery x 8.25 x temp. rise x 1.0 FORMULAS & FACTS TEMP °F RISE STEEL COPPER Linear expansion of pipe 50° 0.38˝ 0.57˝ – in inches per 100 Ft. 100° .076˝ 1.14˝ 125° .092˝ 1.40˝ 150° 1.15˝ 1.75˝ Grain – 1 grain per gallon = 17.1 Parts Per million (measurement of water hardness) TC-092 FORMULAS & FACTS GPH (Gas) = One gallon of Propane gas contains (BTU/H Input X % Eff.) divided by about 91,250 BTU of heat.