Constructivism [Extracts], 1922

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Descargar Descargar

HI INCUBANDO PROCESOS EN CLAVE DE _ Hábitat Inclusivo ECONOMIA SOCIAL Y SOLIDARIA. AUTORES: Propuesta del Programa Universitario en Incubación Social de la Universidad Nacional Lic. Anna Daga Lic. Santiago Errecalde de Quilmes Prof. Graciela Fernández Lic. Nancy Marchand Anna Daga, Graciela Fernández y Nancy El Programa Universitario de Incubación Social se propone Marchand son Directora, responsable vincular las funciones de docencia, investigación y extensión del Área de Proyectos y aistente técnica para el fortalecimiento de procesos de innovación sociotécnica y respectivamente del Programa Universitario de Incubación Social de valoración económica. Se propone la construcción de equipos (PUIS) de la Universidad Nacional de interdisciplinarios y multiactorales nucleados en Incubadoras Quilmes. Universitarias en Economía Social y Solidaria. El siguiente artículo busca presentar la propuesta del Programa Santiago Errecalde es Licenciado en Comunicación Social, docente- Universitario de Incubación Social en general y algunas de las investigador de la UNQ. Dirige la propuestas y desafíos de la Incubadora Universitaria en Incubadora Universitaria en Economía Social y Solidaria en Diseño y Economía Social y Solidaria de Diseño y Comunicación. Comunicación del Programa Universitario de Incubación Social. El Programa Universitario de Incubación Social en Economía Social y Solidaria (PUIS) (1) es una propuesta transversal, que se comienza a implementar en la CONTACTO: Universidad Nacional de Quilmes (UNQ) a partir del año 2013. El PUIS [email protected] [email protected] depende de la Secretaría de Extensión Universitaria en articulación con la [email protected] [email protected] Secretaría de Innovación y Transferencia Tecnológica, como propuesta para incubar procesos generadores de valor socio-económico e innovación social y Palabras Claves: tecnológica, en el marco del desarrollo estratégico del sector de la Economía Incubación Proceso Social y Solidaria (ESS). -

"The Architecture of the Book": El Lissitzky's Works on Paper, 1919-1937

"The Architecture of the Book": El Lissitzky's Works on Paper, 1919-1937 The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Johnson, Samuel. 2015. "The Architecture of the Book": El Lissitzky's Works on Paper, 1919-1937. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:17463124 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA “The Architecture of the Book”: El Lissitzky’s Works on Paper, 1919-1937 A dissertation presented by Samuel Johnson to The Department of History of Art and Architecture in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History of Art and Architecture Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts May 2015 © 2015 Samuel Johnson All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Professor Maria Gough Samuel Johnson “The Architecture of the Book”: El Lissitzky’s Works on Paper, 1919-1937 Abstract Although widely respected as an abstract painter, the Russian Jewish artist and architect El Lissitzky produced more works on paper than in any other medium during his twenty year career. Both a highly competent lithographer and a pioneer in the application of modernist principles to letterpress typography, Lissitzky advocated for works of art issued in “thousands of identical originals” even before the avant-garde embraced photography and film. -

Aleksandr Rodchenko. Model Workers' Club, Soviet Pavilion at The

Downloaded from http://direct.mit.edu/octo/article-pdf/doi/10.1162/OCTO_a_00147/1754067/octo_a_00147.pdf by guest on 26 September 2021 Aleksandr Rodchenko. Model Workers’ Club, Soviet pavilion at the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels in Paris. 1925. © Estate of Alexander Rodchenko/RAO, Moscow/VAGA, New York. Labor Demonstrations: Aleksei Gan’s Island of the Young Pioneers , Dziga Vertov’s Kino-Eye , and the Rationalization of Artistic Labor* Downloaded from http://direct.mit.edu/octo/article-pdf/doi/10.1162/OCTO_a_00147/1754067/octo_a_00147.pdf by guest on 26 September 2021 KRISTIN ROMBERG Of Russian Constructivism’s manifold demonstration pieces, the model workers’ club that Aleksandr Rodchenko exhibited in Paris in 1925 is one of the best. Its economy of materials and transparent structural logic exemplify Constructivism’s rationalist bid for a socialist aesthetics, while its function as a club models the ideal of enlightened recreation as the partner to unalienated labor. 1 Visible in the well-known photograph of the club are posters for the two films that are the subject of this essay. Both were conceived as demonstration pieces in their own right. The poster in the center, also designed by Rodchenko, is for Dziga Vertov’s first feature-length film, Kino-Eye . The one to the right, with the pared-down typographic layout, advertises Aleksei Gan’s Island of the Young Pioneers .2 Both films were made in 1924 and featured the Young Pioneers, the Soviet youth organization for children ages ten to fifteen founded in 1922 on the model of the Boy Scouts. Both were produced as examples of a new approach to filmmaking called “the demonstration of everyday life.” But while Kino-Eye has gone on to be celebrated as the closest thing to Constructivism in cinema, 3 Island has only been mentioned in passing, and even then as a complete disaster. -

Index Figures in Bold Refer to the Biographies and / Or Illustrations A

Index Figures in bold refer to the biographies Kenneth Arrow 406 Beau 87 and / or illustrations H.C. Artmann 418, 481,481 Gottfried Bechtold 190, 221,356, 362, Boris Arvatov 61 362, 418, 498, 499, W.R. Ashby 328 499 a Michael Atiyah 255 Johannes R. Becker 58 Karl Abraham 522, 523, 528, 530- Carl Aub6ck 68 Konrad Becker 294, 364, 364 532 Augustine 209 Otto Beckmann 294, 357, 357, 546, Raimund Abraham 546, 574, 575, 574, Amadeo Avogadro 162 580 575 R. Axelrod 408 Richard Beer-Hoffmann 448 Antal Abt 241 Alfred Julius Ayer 456 Adolf Behne 67 Friedrich Achleitner 418, 481,481,483, Peter Behrens 66 484, 485, 488, 570 b L~szl6 Beke 504 J~nos Acz~l 251 Johannes Baader 59 Man6 Beke 245 Andor Adam 61 Baader-Meinhof group 577 GySrgy von B~k~sy 32, 122, 418, 431, Alfred Adler 66, 518, 521,521, Mihaly Babits 513 433, 433, 434 529, 533 G~bor Bachman 546, 559, 559, 560, John Bell 189, 212-217, 218 Bruno Adler 71 561 Therese Benedek 522 Raissa Adler 521 Ernst Bachrich 67 Tibor Benedek 522 Theodor W. Adorno 26, 142, 402, 447, Ron Baecker 343 Otto Benesch 473 478 Roger Bacon 185 Walter Benjamin 70, 476 Marc Adrian 106, 106, 142, 146, Alexander Bain 352 Gottfried Benn 589 148, 148, 355 BEla Bal&sz 66, 84, 338-341, 418, Max Bense 108 Robert Adrian X 363,363 444-447,446, 44 7, Jeremy Bentham 405 Endre Ady 442, 444 449-454, 513, 529 Vittorio Benussi 23-26, 24, 25, 29 August Aichhorn 521,524, 527, 528 Nandor Balasz 238 Sophie Benz 525 Howard Aiken 323 Alice B~lint 514, 515, 517-519, Bal&zs BeSthy 418, 504, 505, 504, Alciphon 166 521,521,522 505 Josef Albers 123 Mihaly Balint 513-516, 518, 522, (:tienne BEothy 55, 57, 69, 368, 384, David Albert 188 522 385, 384-386 Leon Battista Alberti 166, 354 Hugo Ball 525 Anna B~othy-Steiner 55, 384 Bernhard Alexander 521 Giacomo Balla 19,41 Gyula Benczur 71 Franz Gabriel Alexander 521,522 Richard Baltzer 242 Max Benirschke 38 J.W. -

Dziga Vertov, the First Shoemaker of Russian Cinema1

Dziga Vertov, The First Shoemaker of Russian Cinema1 Devin Fore Princeton University Abstract We are told that the mechanization of production has dire effects on the functionality of language as well as human capacities for symbolic communication in general. This expropriation of language by the machine results in the deterioration of the traditional political public sphere, which once privileged language as the exclusive medium of intersubjectivity and agency. The essay argues that the work of the Soviet media artist Dziga Vertov, especially his 1931 “film-thing” En- thusiasm, sought to redress the antagonism between technology and politics faced by modern industrial societies. Vertov’s public sphere was one that did not privilege language and abstract discourse, but that incorporated all manner of material objects as means of commu- nication. As Vertov instructed, the public sphere must move beyond its linguistic bias to embrace industrial commodities as communica- tive social media. 1. This article is excerpted from a longer paper that examines Dziga Vertov’s work with television, but that cannot appear here in its entirety because of exigencies of space. Postponing the discussion of early television’s position within the Soviet media land- scape for a later context, the present article limits itself to the exposition of two argu- ments: the first section addresses the fate of political discourse within modern regimes of industrial production; then, through an analysis of one passage from Vertov’s film Enthusiasm (1931), the second section considers Vertov’s strategies for forging new modes of political agency within the sphere of technical production. Configurations, 2010, 18:363–382 © 2011 by The Johns Hopkins University Press and the Society for Literature and Science. -

„Lef“ and the Left Front of the Arts

Slavistische Beiträge ∙ Band 142 (eBook - Digi20-Retro) Halina Stephan „Lef“ and the Left Front of the Arts Verlag Otto Sagner München ∙ Berlin ∙ Washington D.C. Digitalisiert im Rahmen der Kooperation mit dem DFG-Projekt „Digi20“ der Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek, München. OCR-Bearbeitung und Erstellung des eBooks durch den Verlag Otto Sagner: http://verlag.kubon-sagner.de © bei Verlag Otto Sagner. Eine Verwertung oder Weitergabe der Texte und Abbildungen, insbesondere durch Vervielfältigung, ist ohne vorherige schriftliche Genehmigung des Verlages unzulässig. «Verlag Otto Sagner» ist ein Imprint der Kubon & Sagner GmbH. Halina Stephan - 9783954792801 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 05:25:44AM via free access S la v istich e B eiträge BEGRÜNDET VON ALOIS SCHMAUS HERAUSGEGEBEN VON JOHANNES HOLTHUSEN • HEINRICH KUNSTMANN PETER REHDER JOSEF SCHRENK REDAKTION PETER REHDER Band 142 VERLAG OTTO SAGNER MÜNCHEN Halina Stephan - 9783954792801 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 05:25:44AM via free access 00060802 HALINA STEPHAN LEF” AND THE LEFT FRONT OF THE ARTS״ « VERLAG OTTO SAGNER ■ MÜNCHEN 1981 Halina Stephan - 9783954792801 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 05:25:44AM via free access Bayerische Staatsbibliothek München ISBN 3-87690-186-3 Copyright by Verlag Otto Sagner, München 1981 Abteilung der Firma Kubon & Sagner, München Druck: Alexander Grossmann Fäustlestr. 1, D -8000 München 2 Halina Stephan - 9783954792801 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 05:25:44AM via free access 00060802 To Axel Halina Stephan - 9783954792801 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 05:25:44AM via free access Halina Stephan - 9783954792801 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 05:25:44AM via free access 00060802 CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................ -

Constructivism (Art) 1 Constructivism (Art)

Constructivism (art) 1 Constructivism (art) Constructivism was an artistic and architectural philosophy that originated in Russia beginning 1919, which was a rejection of the idea of autonomous art in favour of art as a practice for social purposes. Constructivism as an active philosophy lasted until about 1934, greatly effecting the art of the Weimar Republic and elsewhere, before being replaced by Socialist Realism. Some of its motifs have been reused sporadically since. Beginnings The term Construction Art was first used as a derisive term by Kazimir Malevich to describe the work of Alexander Rodchenko during 1917. Constructivism first appears as a positive term in Naum Gabo's Realistic Manifesto of 1920. Alexei Gan used the word as the title of his book Constructivism, which was printed during 1922.[1] Constructivism was a post-World War I development of Russian Futurism, and particularly of the 'corner-counter reliefs' of Vladimir Tatlin, which had been exhibited during 1915. The term itself would be invented by the sculptors Antoine Pevsner and Naum Photograph of the first Constructivist Exhibition, 1921 Gabo, who developed an industrial, angular style of work, while its geometric abstraction owed something to the Suprematism of Kasimir Malevich. The teaching basis for the new ohilosophy was established by The Commissariat of Enlightenment (or Narkompros) the Bolshevik government's cultural and educational ministry directed by Anatoliy Vasilievich Lunacharsky who suppressed the old Petrograd Academy of Fine Arts and the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture during 1918. IZO, the Commissariat's artistic bureau, was managed during the Russian Civil War mainly by Futurists, who published the journal Art of the Commune. -

Make Whichever You Find Work

54 | variant 41 | SPrin G 2011 Make Whichever You Find Work Anthony Iles & Marina Vishmidt ‘Art’s double character as both autonomous and fait Value is the capitalist category par excellence social is incessantly reproduced on the level of its – the category and lens through which every autonomy.’ – Theodor Adorno thing, every object and all social relations are viewed. Value, with its twin poles of use-value and ‘If you take hold of a samovar by its stubby legs, you exchange-value, is the core of the real abstraction can use it to pound nails, but that is not its primary that mediates all social relations through the function.’ – Viktor Shklovsky commodity. ‘[...] there is no use-value other than in the form of Introduction value in capitalist society, if value and capital constitute The recent uptake of the post-autonomist a forceful, totalising form of socialisation that shapes immaterial labour thesis draws cultural every aspect of life.’3 practitioners closer to the critical self-recognition In a society organised by the abstraction of of their own labour (waged and otherwise) as value, that is, a society in which profit is the alienated, as well its formal commonality with imperative for co-operation and production, the other kinds of affective labour at large.1 Art chief product not the commodity but the class finds itself in a new relation with abstract value, relation between capital and labour: this is why whether it’s the typical forms of contemporary it makes more sense to speak of capitalism as a work or financial mechanisms. -

CLUB of the NEW SOCIAL TYPE Yixin Zhou Arch 646: History And

SOCIALISM AND REPRESENTATIONAL UTOPIA: CLUB OF THE NEW SOCIAL TYPE Yixin Zhou Arch 646: History and Theory of Architecture III Research Paper Dec. 14, 2016 Zhou !2 Abstract This paper studies the “Club of the New Social Type” by Ivan Leonidov in 1928, a research study project for a prototype of workers’ club. As a project in the early stage of Leonidov’s career, it embodies various sources of influences upon the architect from Suprematism to Constructivism. The extremity in the abstraction of forms, specific consideration of programs and the social ambition of Soviet avant-garde present themselves in three different dimensions. Therefore, the paper aims to analyze the relationships of the three aspects to investigate the motivation and thinking in the process of translating a brief into a project. Through the close reading of the drawings against the historical context, the paper characterizes the project as socialism and representational utopia. The first part of the paper would discuss the socialist aspect of the “Club of the New Social Type”. I will argue that the project demonstrates Leonidov’s interest in collective rather than individual not only spatially, but also in term of mass behavior and program concern. In the second part, the arguments will be organized on the representation technique in the drawings which renders the project in a utopian aesthetic. It reveals the ambition that the club would function as a prototype for the society and be adopted universally. Throughout the paper, the project would be constantly situated in the genealogy of architectural history for a comparison of ideas. -

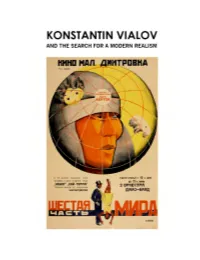

Konstantin Vialov and the Search for a Modern Realism” by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph

Aleksandr Deineka, Portrait of the artist K.A. Vialov, 1942. Oil on canvas. National Museum “Kyiv Art Gallery,” Kyiv, Ukraine Published by the Merrill C. Berman Collection Concept and essay by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph. D. Edited by Brian Droitcour Design and production by Jolie Simpson Photography by Joelle Jensen and Jolie Simpson Research Assistant: Elena Emelyanova, Research Curator, Rare Books Department, Russian State Library, Moscow Printed and bound by www.blurb.com Plates © 2018 the Merrill C. Berman Collection Images courtesy of the Merrill C. Berman Collection unless otherwise noted. © 2018 The Merrill C. Berman Collection, Rye, New York Cover image: Poster for Dziga Vertov’s Film Shestaia chast’ mira (A Sixth Part of the World), 1926. Lithograph, 42 1/2 x 28 1/4” (107.9 x 71.7 cm) Plate XVII Note on transliteration: For this catalogue we have generally adopted the system of transliteration employed by the Library of Congress. However, for the names of artists, we have combined two methods. For their names according to the Library of Congress system even when more conventional English versions exist: e.g. , Aleksandr Rodchenko, not Alexander Rodchenko; Aleksandr Deineka, not Alexander Deineka; Vasilii Kandinsky, not Wassily Kandinsky. Surnames with an “-ii” ending are rendered with an ending of “-y.” But in the case of artists who emigrated to the West, we have used the spelling that the artist adopted or that has gained common usage. Soft signs are not used in artists’ names but are retained elsewhere. TABLE OF CONTENTS 7 - ‘A Glimpse of Tomorrow’: Konstantin Vialov and the Search for a Modern Realism” by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph. -

INTRODUCTION Embedded Aesthetics and Situated History

INTRODUCTION Embedded Aesthetics and Situated History YEAR BEFORE JOINING ALEKSEI GAN in founding the Working Group of Constructivists, Varvara Stepanova A noted a peculiar orientation in her future colleague. In March 1920, she recorded in her diary with apparent bemuse- ment, “Gan considers agitation as important as creating a work.”1 As cofounder of the working group, the framer of their theoretical program, and the only person involved in nearly all of constructivism’s manifestations across disciplines—including mass festivals, the “laboratory period,” theater, industrial design, print, cinema, and architecture—Gan was ubiquitous within the movement, even arguably its central figure, but his position was also idiosyncratic. Never a professional artist per se, he worked primarily as a political organizer. Stepanova’s comment percep- tively points to the fundamental insight Gan brought to the constructivist project from that experience: within a society organized around mass production and public spaces, part of the construction of any object was the construction of a broad public for it. From Gan’s standpoint, the “work of art” was less an object 1 58905int.indd 1 2018-09-13 10:24 AM than a labor process through which new publics were constituted and new modes of sociality cultivated. This book presents a new understanding of Russian constructivism by retelling its story from that perspective, with Gan as its central protagonist. At times that tale will feel heroic, but equally oftentimes tragic. Mostly it will be a gritty on-the-ground story about bumbling through the trials and errors of working to shape an evolving political field from a position deeply embedded within it. -

Cultural Syllabus : Russian Avant-Garde and Radical Modernism : an Introductory Reader

———————————————————— Introduction ———————————————————— THE RUSSIAN AVANT-GARDE AND RADICAL MODERNISM An Introductory Reader Edited by Dennis G. IOFFE and Frederick H. WHITE Boston 2012 — 3 — ——————————— RUSSIAN SUPREMATISM AND CONSTRUCTIVISM ——————————— 1. Kazimir Malevich: His Creative Path1 Evgenii Kovtun (1928-1996) Translated from the Russian by John E. Bowlt Te renewal of art in France dating from the rise of Impressionism extended over several decades, while in Russia this process was consoli- dated within a span of just ten to ffteen years. Malevich’s artistic devel- opment displays the same concentrated process. From the very begin- ning, his art showed distinctive, personal traits: a striking transmission of primal energy, a striving towards a preordained goal, and a veritable obsession with the art of painting. Remembering his youth, Malevich wrote to one of his students: “I worked as a draftsman... as soon as I got of work, I would run to my paints and start on a study straightaway. You grab your stuf and rush of to sketch. Tis feeling for art can attain huge, unbelievable proportions. It can make a man explode.”2 Transrational Realism From the early 1910s onwards, Malevich’s work served as an “experimen- tal polygon” in which he tested and sharpened his new found mastery of the art of painting. His quest involved various trends in art, but although Malevich firted with Cubism and Futurism, his greatest achievements at this time were made in the cycle of paintings he called “Alogism” or “Transrational Realism.” Cow and Violin, Aviator, Englishman in Moscow, Portrait of Ivan Kliun—these works manifest a new method in the spatial organization of the painting, something unknown to the French Cub- ists.