Study Regarding the State of Rights of Refugees from the Republic of Croatia 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inscribed 6 (2).Pdf

Inscribed6 CONTENTS 1 1. AVIATION 33 2. MILITARY 59 3. NAVAL 67 4. ROYALTY, POLITICIANS, AND OTHER PUBLIC FIGURES 180 5. SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY 195 6. HIGH LATITUDES, INCLUDING THE POLES 206 7. MOUNTAINEERING 211 8. SPACE EXPLORATION 214 9. GENERAL TRAVEL SECTION 1. AVIATION including books from the libraries of Douglas Bader and “Laddie” Lucas. 1. [AITKEN (Group Captain Sir Max)]. LARIOS (Captain José, Duke of Lerma). Combat over Spain. Memoirs of a Nationalist Fighter Pilot 1936–1939. Portrait frontispiece, illustrations. First edition. 8vo., cloth, pictorial dust jacket. London, Neville Spearman. nd (1966). £80 A presentation copy, inscribed on the half title page ‘To Group Captain Sir Max AitkenDFC. DSO. Let us pray that the high ideals we fought for, with such fervent enthusiasm and sacrifice, may never be allowed to perish or be forgotten. With my warmest regards. Pepito Lerma. May 1968’. From the dust jacket: ‘“Combat over Spain” is one of the few first-hand accounts of the Spanish Civil War, and is the only one published in England to be written from the Nationalist point of view’. Lerma was a bomber and fighter pilot for the duration of the war, flying 278 missions. Aitken, the son of Lord Beaverbrook, joined the RAFVR in 1935, and flew Blenheims and Hurricanes, shooting down 14 enemy aircraft. Dust jacket just creased at the head and tail of the spine. A formidable Vic formation – Bader, Deere, Malan. 2. [BADER (Group Captain Douglas)]. DEERE (Group Captain Alan C.) DOWDING Air Chief Marshal, Lord), foreword. Nine Lives. Portrait frontispiece, illustrations. First edition. -

Volume 126, Number 55 Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139 Tuesday, November 21, 2006 Petition Drafted for Institute Divestment Sudanese Government Cited As “Genocidal”

Drop Date Tomorrow; No School Thursday, Friday MIT’s The Weather Today: Sunny, humid, 88°F (31°C) Oldest and Largest Tonight: Partly cloudy, 66°F (19°C) Tomorrow: Sunny, 86°F (30°C) Newspaper Details, Page 2 Volume 126, Number 55 Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139 Tuesday, November 21, 2006 Petition Drafted For Institute Divestment Sudanese Government Cited as “Genocidal” By Marie Y. Thibault night, the petition had garnered 343 EDITOR IN CHIEF signatures. As an MIT Corporation advisory Zainabadi plans to present the pe- committee continues deliberating tition to MIT Corporation’s Advisory whether MIT should divest from Su- Committee for Shareholder Respon- dan or not, a petition supporting di- sibility at their next meeting before vestment is gathering energy around bringing it before the Corporation’s campus. A lecture planned for next Executive Committee. week is expected to open and add to Graduate Student Council Presi- campus discussion about divestment. dent Eric G. Weese G, also a member The petition reads, “We, the un- of the ACSR, said that the committee dersigned, request the Massachusetts checked the number of signatures on Institute of Technology divest from the petition at its last meeting. offending companies doing business Zainabadi hopes that the ACSR with the genocidal government in will decide to divest and will choose Sudan immediately (no later than De- a model of “targeted divestment” for CHRIS PENTACOFF cember 31st 2006).” the divestment, as was proposed by MIT hackers changed the Harvard motto “Veritas” to “HUGE EGO” on both sides of the Harvard score- The petition’s author, Kayvan the Sudan Divestment Task Force. -

Kent1258151570.Pdf (651.73

When Two Worlds Collide: The Allied Downgrading Of General Dragoljub “Draža” Mihailović and Their Subsequent Full Support for Josip Broz “Tito” A thesis submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Jason Alan Shambach Csehi December, 2009 Thesis written by Jason Alan Shambach Csehi B.A., Kent State University, 2005 M.A., Kent State University, 2009 Approved by Solon Victor Papacosma , Advisor Ken Bindas , Chair, Department of History John R. D. Stalvey , Dean, College of Arts and Sciences ii Table of Contents Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………………….iv Prelude…………………………………………………………………………………..1 Chapter 1…………….………………………………………………………………....11 A Brief Overview of the Existing Literature and an Explanation of Balkan Aspirations Chapter 2.........................................................................................................................32 Churchill’s Yugoslav Policy and British Military Involvement Chapter 3….……………………………………………………………………………70 Roosevelt’s Knowledge and American Military Involvement Chapter 4………………….………………………………………………...………...101 Fallout from the War Postlude….……………………………………………………………….…...…….…131 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………….….142 iii Acknowledgements The completion of this thesis could not have been attained without the help of several key individuals. In particular, my knowledgeable thesis advisor, S. Victor Papacosma, was kind enough to take on this task while looking to be on vacation on a beach somewhere in Greece. Gratitude is also due to my other committee members, Mary Ann Heiss, whose invaluable feedback during a research seminar laid an important cornerstone of this thesis, and Kevin Adams for his participation and valuable input. A rather minor thank you must be rendered to Miss Tanja Petrović, for had I not at one time been well-acquainted with her, the questions of what had happened in the former Yugoslavia during World War II as topics for research seminars would not have arisen. -

History of Women Reel Listing

History of Women Reel Listing Abailard, Pierre, 1079-1142. Agrippa, von Nettesheim, Heinrich Cornelius, Letters of Abelard and Heloise. 1486?-1535. London, Printed for J. Watts. 1743 The glory of women; or, A treatise declaring the Item identification number 1; To which is prefix'd a excellency and preheminence of women above men, particular account of their lives, amours, and which is proved both by scripture, law, reason, and misfortunes: extracted chiefly from Monsieur Bayle. authority, divine and humane. Translated from the French by the late John Hughes, London, Printed for Robert Ibbitson. 1652 esq. 7th ed. Item identification number 7; Written first in Latine Reel: 1 by Henricus Cornelius Agrippa ... and now translated into English for the vertuous and beautifull female Adams, Hannah, 1755-1832. sex of the commonwealth of England. by Edvv. An alphabetical compendium of the various sects Fleetvvood, gent. which have appeared in the world from the beginning Reel: 1 of the Christian æ ra to the present day. Boston, Printed by B. Edes & sons. 1784 Alberti, Marcello, b. 1714. Item identification number 3; with an appendix, Istoria della donne scientiate del dotore Marcello containing a brief account of the different schemes of Alberti. religion now embraced among mankind. The whole In Napoli, Per Felice Mosca. 1740 collected from the best authors, ancient and modern. Item identification number 8. Reel: 1 Reel: 1 Adams, Hannah, 1755-1832. Albertus Magnus, Saint, bp. of Ratisbon, 1193?- A summary history of New-England, from the 1280. first settlement at Plymouth, to the acceptance of the Albertus Magnus, de secretis mulierum. -

(C) Clive Barker 28.7.86 115 Flood Street, London. SW3 01-352-4195

HELLRAISER A Screenplay by Clive Barker Paragan Film Productions Ltd (C) Clive Barker 28.7.86 115 Flood Street, London. SW3 01-352-4195 1 1 TITLE SEQUENCE In darkness, a blood-curdling cacophony: the squeal of unoiled winches, the rasp of hooks and razors being sharpened; and worse, the howl of tormented souls. Above this din one particular victim yells for mercy - a mixture of tears and roars of rage. By degrees his incoherent pleas are drowned out by the surrounding tumult, until without warning his voice pierces the confusion afresh - this time reduced to naked scream. And with the sound, an image. A house: Number 55, Lodovico Street, an old, three storey, late Victorian house, with gaunt trees lining its overgrown garden. Its curtains are drawn, there is newspaper over its top window. The titles begin to run, as we approach the house down the driveway. We move inside, to the hallway. The cries are louder now. Room by room, we explore the empty house, while the titles continue to run. It has been left empty for many years, though much of its furniture remains, covered in dust-sheets. On the mantelpiece of one room, a plaster saint. In the kitchen, evidence of life here. Opened tins; bread; bottles of spirits; a glass. We move upstairs, gliding along the corridor of the lower landing. The din is furious now. On the floor of one room, a makeshift bed: blankets strewn; an open suitcase; more liquor. We move up a flight and approach a room off the upper landing, the door of which is ajar. -

Love Croatian Film · 2014 Croatian Films – Coming up in 2014 May 2014 WHAT’S LOVE GOT CONTENTS

love croatian film · 2014 Croatian Films – Coming Up in 2014 may 2014 WHAT’S LoVE goT ConTEnTS To Do WiTH iT? Feature Film — 2013 second half of the year Šuti · Hush… Lukas Nola · 8 Vis- -Vis Nevio Marasović · 8 Kauboji · Cowboys Tomislav Mršić · 8 Majstori · Handymen Dalibor Matanić · 10 Projekcije · Projections Zrinko Ogresta · 10 Hitac · One Shot Robert Orhel · 10 finished 2014 Duh babe Ilonke · The Little Gipsy Witch Tomislav Žaja · 12 Cure Andrea Štaka · 13 Domoljub · A Patriotic Man · Isänmaallinen mies Arto Halonen · 14 Inferno Vinko Möderndorfer · 15 Most na kraju svijeta · The Bridge at the End of the World Branko Ištvančić · 16 Otok ljubavi · Love Island Jasmila Žbanić · 17 Spomenik Majklu Džeksonu · Monument to Michael Jackson Darko Lungulov · 18 Sudilište · Judgement · Sadilishteto Stephan Komandarev · 19 Takva su pravila · These Are the Rules Ognjen Sviličić · 20 ‘What’s love got to do with it?’ You may start by singing this Ti mene nosiš · You Carry Me Ivona Juka · 21 Zagreb Cappuccino Vanja Sviličić · 22 question in the r’n’b voice of the energetic grandmother. post-production Broj 55 · Number 55 Kristijan Milić · 23 And I will scream back: ‘A lot!’ In Croatia, as in many other Kosac · The Reaper Zvonimir Jurić · 24 Lazar · Lazarus Svetozar Ristovski · 25 Eastern European countries, filmmaking is still alive, mostly Ljubav ili smrt · Love or Death Daniel Kušan · 26 Svinjari · The Enchanting Porkers Ivan Livaković · 27 as the fruit of persistent passion. In order to build up a Život je truba · Life Is a Trumpet Antonio Nuić · 28 decent filmmaking support system, as we have managed Short Fiction Film — 2013 festival highlights Balavica · Little Darling Igor Mirković · 30 to do in Croatia, one often has to swim upstream, but Ko da to nisi ti · So Not You Ivan Sikavica · 30 Kutija · Boxed Nebojša Slijepčević · 30 one also has to walk in the clouds. -

An Analysis of Idiomatic Expression Found on American Sniper Movie

AN ANALYSIS OF IDIOMATIC EXPRESSION FOUND ON AMERICAN SNIPER MOVIE THESIS Submitted in Partially Fulfillment of the Requirement For Degree of Bachelor of Education In english Education By Muhammad Ilham Subkhan 133411009 EDUCATION AND TEACHER TRAINING FACULTY WALISONGO STATE ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY SEMARANG 2018 THESIS STATEMENT I am the student with the following identity: Name : Muhammad Ilham Subkhan Student Number : 133411009 Field Of Study : English Language Education certify that the thesis is definitely my own work. I am completely responsible for the content of this thesis. Other reseacrher’s opinions or findings included in this thesis are quoted or cited in accordance with ethical standard. Semarang, May 19th, 2018 The Researcher, Muhammad Ilham Subkhan Student Number: 133411009 ii KEMENTERIAN AGAMA R.I. UNIVERSITAS ISLAM NEGERI WALISONGO FAKULTAS ILMU TARBIYAH DAN KEGURUAN Jl. Prof. Dr. Hamka (Kampus II) Ngaliyan Semarang Telp. 024-7601295 Fax. 7615387 RATIFICATION Thesis with the following identity: Title : “An Analysis of Idiomatic Expression Found On American Sniper Movie” Name : Muhammad Ilham Subkhan Student Number : 133411009 Department : English Language Education had been ratified by the board of examiner of education and teacher training faculty Walisongo State Islamic University and can be received as one of requireements for gaining the Bachelor Degree in English Language Education. Semarang, July 30 th, 2018 THE BOARD OF EXAMINERS Chairperson Secretary Dra. Hj. Siti Mariam, M.Pd Muhammad Nafi Annury, M.Pd NIP.19650727 199203 2 002 NIP.1972880719 2005501 1 007 Examiner I Examiner II Siti Tarwiyah, S.S., M.Hum. Nadiah Ma’mun , M.Pd. NIP.19721108 199903 2 001 NIP.19781103 200701 2 016 Advisor I Advisor II Dra. -

Croatian Cinema 01, Magazine

INTRODUCTION A GREAT QUEST FOR THE NEW HAS BEGUN Priest’s Children, Lapitch, the Little Shoemaker and The Mysterious Boy have become blockbust- ers and Cowboys (with 34,000 views) became the cult film of the year. Croatian minority and ma- jority co-productions have travelled extensively and won a great number of international awards, in particular Halima’s Path by Arsen Ostojić, Cir- hrvoje hribar cles by Srđan Golubović, A Stranger by Bobo Jelčić. ceo of croatian n Russia, I was once shown a photograph of I am most excited about the trio Cowboys, A Stran- audiovisual centre a commissary with a leather collar who was ger and Projections. These three films, which bare Iknown for jumpstarting Andrej Tarkovsky’s no resemblance to one another, are also radically career. The faces of the gentlemen in bowler hats, different from any other film that was previous- the board members of RKO Pictures that have ly shot in Croatia. A great quest for a new and un- granted Orson Welles permission to filmCitizen known kind of film has begun in Croatia, one that Kane weren’t any more attractive. I don’t believe will be able to tell “new anecdotes of this unusual that you would like to spend your summer vaca- country”, as Croatia’s famous author Ivana Brlic tion on an island with any of them. I think of those Mazuranic would put it. photos while watching myself in a mirror. I admit We have recently asked documentary author and that I do not know the answer to the question of producer Dana Budisavljević to join an interna- what exactly is the role of the system in the fate tional presentation of the Croatian audiovisual of an individual work of art. -

Appendix 1 the World of Cinema in Argentina

Appendix 1 The World of Cinema in Argentina A revelation on January 17, 2002. I am headed to the Citibank on Cabildo Street, where I have a savings account. I try to enter the bank but cannot because of the number of people waiting. So I give up on my errand. I cross the street to return home, and from the sidewalk facing the bank I see, for the first time, the building in which it is housed. The familiar is made strange; shortly after, it becomes familiar again, but in a slightly disturbing way. I recognize the building’s arches and moldings, its fanciful rococo façade. I recognize the Cabildo movie theater, in which I saw so many movies as an adolescent. Although I have been coming to this bank for years, I have never before made this connection. I know movie theaters that have been transformed into video arcades, into evangelical churches,1 into parking garages, even into bookstores. Yet I knew of none that had become a bank. All my savings were housed in a space that had been shadows, lights, images, sounds, seats, a screen, film. I remember that around the age of sixteen, I saw Robert Redford’s Ordinary People (1980) on the same day as Alain Resnais’ Last Year at Marienbad (1961) in the Hebraica theater. Two or three movies a day (video didn’t exist then) in which almost everything was film, film, and only film. These are the adolescent years in which cinephilia is born: a messy love, passionate, without much judgment. -

Young Sheldon Episode Guide Episodes 001–083

Young Sheldon Episode Guide Episodes 001–083 Last episode aired Thursday May 13, 2021 www.cbs.com © © 2021 www.cbs.com © 2021 www.myfanbase.de © 2021 tvtropes.org © 2021 www.imdb.com The summaries and recaps of all the Young Sheldon episodes were downloaded from http://www.imdb.com and http: //www.cbs.com and http://www.myfanbase.de and http://tvtropes.org and processed through a perl program to transform them in a LATEX file, for pretty printing. So, do not blame me for errors in the text ! This booklet was LATEXed on May 16, 2021 by footstep11 with create_eps_guide v0.68 Contents Season 1 1 1 Pilot ...............................................3 2 Rockets, Communists, and the Dewey Decimal System . .5 3 Poker, Faith, and Eggs . .7 4 A Therapist, a Comic Book and a Breakfast Sausage . .9 5 A Solar Calculator, a Game Ball, and a Cheerleader’s Bosom . 11 6 A Patch, a Modem, and a Zantac . 13 7 A Brisket, Voodoo, and Cannonball Run . 15 8 Cape Canaveral, Schrodinger’s Cat, and Cyndi Lauper’s Hair . 17 9 Spock, Kirk, and Testicular Hernia . 19 10 An Eagle Feather, a String Bean and an Eskimo . 21 11 Demons, Sunday School, and Prime Numbers . 23 12 A Computer, a Plastic Pony, and a Case of Beer . 25 13 A Sneeze, Detention, and Sissy Spacek . 27 14 Potato Salad, a Broomstick, and Dad’s Whiskey . 29 15 Dolomite, Apple Slices, and a Mystery Woman . 31 16 Killer Asteroids, Oklahoma, and a Frizzy Hair Machine . 33 17 Jiu-Jitsu, Bubble Wrap, and Yoo-Hoo . -

SPRING 2010 - Volume 57, Number 1 SERVING THOSE WHO SERVE

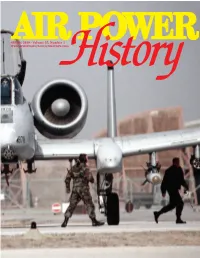

SPRING 2010 - Volume 57, Number 1 WWW.AFHISTORICALFOUNDATION.ORG SERVING THOSE WHO SERVE Every day U.S. service men and women place themselves in harm’s way to accomplish their mission – protecting our nation and ensuring its security. Our mission at EADS North America is to provide the equipment and support necessary for them to do their job and come home safely to their families. From helicopters and patrol aircraft to reliable emergency communications, EADS North America proudly serves those who serve. Spring 2010 - Volume 57, Number 1 WWW.AFHISTORICALFOUNDATION.ORG Features 100 Missions North: History and Traditions Jeff Duford 4 “Fiasco” Revisited: The Air Corps & the 1934 Air Mail Episode Kenneth P. Werrell 12 Reflections on the Balkan Wars Benjamin S. Lambeth 30 “History Makes You Smart—Heritage Makes you Proud” Jacob Neufeld 44 Book Reviews If Mahan Ran the Great Pacific War: An Analysis of World War II Naval Strategy By John A. Adams Reviewed by John F. O’Connell 48 Space Shuttle Main Engine: The First Twenty Years and Beyond By Robert E. Biggs Reviewed by Sherman N. Mullin 48 Embry-Riddle at War: Aviation Training during World War II By Stephan G. Craft Reviewed by Al Mongeon 48 Clipping the Clouds: How Air Travel Changed the World By Marc Dierikx Reviewed by Robert W. Allen 49 Magnum! The Wild Weasels in Desert Storm By Braxton Eisel and Jim Schreiner Reviewed by Michael A. Nelson 50 A Fiery Peace in a Cold War: Bernard Schriever and the Ultimate Weapon By Neil Sheehan Reviewed by Lawrence R. Benson 50 Harnessing the Heavens: National Defense through Space By Paul G. -

Cinema and Memory of the 'Homeland War'

HIDDEN DIALOGUES WITH THE PAST: CINEMA AND MEMORY OF THE ‘HOMELAND WAR’ By Tamara Kolarić Submitted to Central European University Doctoral School of Political Science, Public Policy and International Relations In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science Supervisors: prof. Nenad Dimitrijević CEU eTD Collection prof. Lea Sgier Budapest, Hungary December 2018 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this dissertation contains no materials accepted for any other degree in any other institution. This dissertation contains no materials previously written and/or published by another person, except where appropriate acknowledgment is made in the form of bibliographical reference. Tamara Kolarić 31st December 2018 CEU eTD Collection i ABSTRACT This dissertation analyses the relationship between fiction films and collective memory in Croatia specifically related to the memory of the ‘Homeland War’ – the armed conflict which took place in the country between 1991 and 1995. The analysis is based on the films produced in the period between 2001 and 2014. While literature on post-Yugoslav cinema is abundant, little has been written about the role films play – or have the potential to play – in shaping collective memory. Inspired by the adverse reactions fiction films frequently caused in public, this dissertation started from the following question: what was it that these films “do” – or were perceived to do – to the story of the war? This was then broken down into two research questions: as a point of departure, I looked into whether the war was present in contemporary Croatian cinema, i.e. whether films offered material with regard to the war.