Terrorists/Liberators: Researching and Dealing with Adversary Social

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report of the 7 July Review Committee

cover2.qxd 5/26/06 3:41 pm Page 1 Report of the 7 July Review Committee - Volume 2 Volume - Committee Report of the 7 July Review Report of the 7 July Review Committee Volume 2: Views and information from organisations Greater London Authority City Hall The Queen’s Walk More London London SE1 2AA www.london.gov.uk Enquiries 020 7983 4100 June 2006 Minicom 020 7983 4458 LA/May 06/SD D&P Volume 2: Views and information from organisations Contents Page Transcript of hearing on 3 November 2005 3 Transport for London, Metropolitan Police Service, City of London Police, British Transport Police, London Fire Brigade and London Ambulance Service Transcript of hearing on 1 December 2005 Telecommunications companies: BT, O2, Vodafone, Cable & Wireless 61 Communication with businesses: London Chamber of Commerce & Industry 90 and Metropolitan Police Service Transcript of hearing on 11 January 2006 Local authorities: Croydon Council (Local Authority Gold on 7 July), Camden 109 Council, Tower Hamlets Council and Westminster City Council Health Service: NHS London, Barts & the London NHS Trust, Great Ormond 122 Street Hospital, Royal London Hospital and Royal College of Nursing Media: Sky News, BBC News, BBC London, ITV News, LBC News & Heart 132 106.2, Capital Radio and London Media Emergency Forum, Evening Standard, The Times Transcript of hearing on 1 March 2006 147 Ken Livingstone, Mayor of London Sir Ian Blair, Metropolitan Police Commissioner Written submissions from organisations Metropolitan Police 167 City of London Police 175 London Fire Brigade -

9783642379826.Pdf

Giorgio De Michelis Francesco Tisato Andrea Bene Diego Bernini (Eds.) 116 Arts and Technology Third International Conference, ArtsIT 2013 Milan, Italy, March 2013 Revised Selected Papers 123 Lecture Notes of the Institute for Computer Sciences, Social Informatics and Telecommunications Engineering 116 Editorial Board Ozgur Akan Middle East Technical University, Ankara, Turkey Paolo Bellavista University of Bologna, Italy Jiannong Cao Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong Falko Dressler University of Erlangen, Germany Domenico Ferrari Università Cattolica Piacenza, Italy Mario Gerla UCLA, USA Hisashi Kobayashi Princeton University, USA Sergio Palazzo University of Catania, Italy Sartaj Sahni University of Florida, USA Xuemin (Sherman) Shen University of Waterloo, Canada Mircea Stan University of Virginia, USA Jia Xiaohua City University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong Albert Zomaya University of Sydney, Australia Geoffrey Coulson Lancaster University, UK Giorgio De Michelis Francesco Tisato Andrea Bene Diego Bernini (Eds.) Arts and Technology Third International Conference, ArtsIT 2013 Milan, Italy, March 21-23, 2013 Revised Selected Papers 13 Volume Editors Giorgio De Michelis Francesco Tisato Andrea Bene Diego Bernini DISCo, University of Milano-Bicocca viale Sarca 336, 20135 Milano, Italy E-mail: {gdemich; tisato; bene; bernini }@disco.unimib.it ISSN 1867-8211 e-ISSN 1867-822X ISBN 978-3-642-37981-9 e-ISBN 978-3-642-37982-6 DOI 10.1007/978-3-642-37982-6 Springer Heidelberg Dordrecht London New York Library of Congress Control Number: 2013935879 CR Subject Classification (1998): J.5, H.5.1, H.5, I.4.9 © ICST Institute for Computer Science, Social Informatics and Telecommunications Engineering 2013 This work is subject to copyright. -

Annual Report 2005

NATIONAL GALLERY BOARD OF TRUSTEES (as of 30 September 2005) Victoria P. Sant John C. Fontaine Chairman Chair Earl A. Powell III Frederick W. Beinecke Robert F. Erburu Heidi L. Berry John C. Fontaine W. Russell G. Byers, Jr. Sharon P. Rockefeller Melvin S. Cohen John Wilmerding Edwin L. Cox Robert W. Duemling James T. Dyke Victoria P. Sant Barney A. Ebsworth Chairman Mark D. Ein John W. Snow Gregory W. Fazakerley Secretary of the Treasury Doris Fisher Robert F. Erburu Victoria P. Sant Robert F. Erburu Aaron I. Fleischman Chairman President John C. Fontaine Juliet C. Folger Sharon P. Rockefeller John Freidenrich John Wilmerding Marina K. French Morton Funger Lenore Greenberg Robert F. Erburu Rose Ellen Meyerhoff Greene Chairman Richard C. Hedreen John W. Snow Eric H. Holder, Jr. Secretary of the Treasury Victoria P. Sant Robert J. Hurst Alberto Ibarguen John C. Fontaine Betsy K. Karel Sharon P. Rockefeller Linda H. Kaufman John Wilmerding James V. Kimsey Mark J. Kington Robert L. Kirk Ruth Carter Stevenson Leonard A. Lauder Alexander M. Laughlin Alexander M. Laughlin Robert H. Smith LaSalle D. Leffall Julian Ganz, Jr. Joyce Menschel David O. Maxwell Harvey S. Shipley Miller Diane A. Nixon John Wilmerding John G. Roberts, Jr. John G. Pappajohn Chief Justice of the Victoria P. Sant United States President Sally Engelhard Pingree Earl A. Powell III Diana Prince Director Mitchell P. Rales Alan Shestack Catherine B. Reynolds Deputy Director David M. Rubenstein Elizabeth Cropper RogerW. Sant Dean, Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts B. Francis Saul II Darrell R. Willson Thomas A. -

'Passing Unnoticed in a French Crowd': the Passing Performances

National Identities ISSN: 1460-8944 (Print) 1469-9907 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cnid20 ‘Passing unnoticed in a French crowd’: The passing performances of British SOE agents in Occupied France Juliette Pattinson To cite this article: Juliette Pattinson (2010) ‘Passing unnoticed in a French crowd’: The passing performances of British SOE agents in Occupied France, National Identities, 12:3, 291-308, DOI: 10.1080/14608944.2010.500469 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/14608944.2010.500469 Published online: 06 Sep 2010. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 912 View related articles Citing articles: 1 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=cnid20 National Identities Vol. 12, No. 3, September 2010, 291Á308 ‘Passing unnoticed in a French crowd’: The passing performances of British SOE agents in Occupied France Juliette Pattinson* University of Strathclyde, UK This article examines the dissimulation, construction and assumption of national identities using as a case study male and female British agents who were infiltrated into Nazi-Occupied France during the Second World War. The British nationals recruited by the SOE’s F section had, as a result of their upbringing, developed a French ‘habitus’ (linguistic skills, mannerisms and knowledge of customs) that enabled them to conceal their British paramilitary identities and ‘pass’ as French civilians. The article examines the diverse ways in which individuals attempted to construct French identities linguistically (through accent and use of vocabulary, slang and swear words), visually (through their physical appearance and clothing) and performatively (by behaving in particular ways). -

HISTORY of WWII INFILTRATIONS INTO FRANCE-Rev62-06102013

Tentative of History of In/Exfiltrations into/from France during WWII from 1940 to 1945 (Parachutes, Plane & Sea Landings) Forewords This tentative of history of civilians and military agents (BCRA, Commandos, JEDBURGHS, OSS, SAS, SIS, SOE, SUSSEX/OSSEX, SUSSEX/BRISSEX & PROUST) infiltrated or exfiltrated during the WWII into France, by parachute, by plane landings and/or by sea landings. This document, which needs to be completed and corrected, has been prepared using the information available, not always reliable, on the following internet websites and books available: 1. The Order of the Liberation website : http://www.ordredelaliberation.fr/english/contenido1.php The Order of the Liberation is France's second national Order after the Legion of Honor, and was instituted by General De Gaulle, Leader of the "Français Libres" - the Free French movement - with Edict No. 7, signed in Brazzaville on November 16th, 1940. 2. History of Carpetbaggers (USAAF) partly available on Thomas Ensminger’s website addresses: ftp://www.801492.org/ (Need a user logging and password). It is not anymore possible to have access to this site since Thomas’ death on 03/05/2012. http://www.801492.org/MainMenu.htm http://www.801492.org/Air%20Crew/Crewz.htm I was informed that Thomas Ensminger passed away on the 03/05/2012. I like to underline the huge work performed as historian by Thomas to keep alive the memory the Carpetbaggers’ history and their famous B24 painted in black. RIP Thomas. The USAAF Carpetbagger's mission was that of delivering supplies and agents to resistance groups in the enemy occupied Western European nations. -

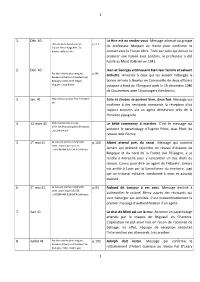

1 1 1. Déc. 40 La Hire Est Au Rendez-Vous. Message Adressé Au

1 1. Déc. 40 La Hire est au rendez-vous. Message adressé au groupe p.224 Histoire de la Résistance en du professeur Morpain au Havre pour confirmer le France. Henri Noguères. T1. Robert Laffont.1967 contact avec la France Libre. Trahi par celui qui devait lui procurer une liaison avec Londres, le professeur a été fusillé au Mont Valérien en 1941. 2. Déc. 40 Jean et Georges embrassent bien leur famille et saluent p.106 Par les nuits les plus longues. Bichette. Annonce à ceux qui les avaient hébergés la Réseaux d’évasion d’aviateurs en Bretagne 1940-1944. Roger bonne arrivée à Newlyn en Cornouaille de deux officiers Huguen. Coop Breizh polonais à bord de l’Emigrant parti le 16 décembre 1940 de Douarnenez avec 19 passagers clandestins. 3. Jan. 41 http://beaucoudray.free.fr/1940.h Toto et Zouzou se portent bien, deux fois. Message qui tm confirme à des résistants normands la réception d’un rapport transmis via un agent demeurant près de la frontière espagnole. 4. 12 mars 41 http://www.plan-sussex- Le bébé commence à marcher. C’est le message qui 1944.net/francais/pdf/infiltrations _en_france.pdf annonce le parachutage d’Eugène Pérot, alias Pépé, du réseau Jade-Fitzroy. 5. 1er mai 41 La lune est pleine d’éléphants p.100 Albert attend près du canal. Message qui autorise verts. Dominique DECEZE. Jamars qui prétend rejoindre un réseau d’évasion de J.LANZMANN &SEGHERS éditeurs. Belgique et du nord de la France par l’Espagne, à se rendre à Marseille pour y rencontrer un des chefs du réseau. -

The Company Journal and "The Feederline"

The Company Journal and "The Feederline" Fire Department News Cambridge, Massachusetts A Class 1 Fire Department From the desk of Chief Gerald R. Reardon Issue #76 Fall 2015 All Companies Working June 24, 2015 – Working Fire, 62 Jackson Circle, Box 75 – heavy smoke and fire showing from Floor #3 of a 4 story brick residential building. No alarms sounding on arrival. Building evacuated prior to arrival. Primary and secondary searches completed, lines stretched. Fire knocked down and confined to a bedroom and hallway. June 24, 2015 – Mutual Aid, Waltham, 3 rd Alarm, 240 Moody Street – Engine 9, Ladder 1, Squad 4 and Division 1 responded to Waltham to assist at their 3rd Alarm fire. June 24, 2015 – 1 Alarm Fire, 85 Hammond Street, Box 614 – companies found trash left by painters on fire in the garage. Small fire extinguished with water can. June 26, 2015 – Mutual Aid, Belmont, Working Fire, 11 Pearl Street – Engine 1, Squad 4 and Division 2 responded to the fire for RIT and Ladder 1 covered at HQ July 2, 2015 – 1 Alarm Fire, Box 94,103 Belmont Street – companies dispatched for smoke in the basement. On arrival Engine 9 and Squad 4 found a small fire in the basement that melted a domestic water pipe which extinguished most of the fire. July 12, 2015 – Mutual Aid Arlington, 3 Alarms, 2 Belton Street, Box 3114 – Engine 4, Squad 2 and Division 2 responded to Arlington for a 2 alarm fire. On scene they assisted by operating hand lines in the interior of the building and overhaul. -

Unabridged AFM Product Guide + Stills

AFM PRODUCTPRODUCTwww.thebusinessoffilmdaily.com/AFM2012ProductGuide/AFMProductGuide.pdfGUIDEGUIDE Hillridge (Parker Posey), the head of the high school soccer team’s two week trip Director: Alex de la Iglesia 108 MEDIA hospital’s charity foundation, reluctantly to Italy. Dynamic friendships, rivalries Writer: Alex de la Iglesia decides to take Adan into her home for a and personal secrets compete in this tale Key Cast: José Mota, Salma Hayek CORPORATION few days. Through his ongoing and of one boy’s stirring coming of age in a Delivery Status: Screening 108 Media Corporation, 225 sometimes inappropriate slogans, Adan foreign land. Year of Production: 2011 Country of Commissioners St., Suite 204,, Toronto, slowly begins to affect Karen and the Origin: Spain Ontario Canada, Tel: 1.637.837.3312, MYN BALA: WARRIORS OF THE dysfunctional relationship she has with In this hilarious comedy, Alex de la http://www.108mediacorp.com, STEPPE her daughter Meghan. Epic Adventure (125 min) Iglesia makes fun of lack of today's [email protected] Director: Akan Satayev morals in media and depiction of Sales Agent, Producer BUFFALO GIRLS Documentary (66min) Kazakhstan, 1729: A ferocious Mongol financial crisis through the eyes of an At AFM: Abhi Rastogi (CEO) Buffalo Girls tells the story of two 8- tribe sweeps across the steppes, and unemployed advertising executive who Office: Loews Hotel Suite 601 year-old-girls, Stam and Pet, both Kazakh sultans leave their people to fend decides to take advantage of an accident AUTUMN BLOOD Director: Reed Morano (Frozen River) professional Muay Thai prizefighters. Set for themselves. Young Sartai and other he has after yet another humiliating work Writer: Stephen Barton and Markus in small villages throughout rural survivors flee to the mountains. -

Andre Borrel & Lise De Baissac

NOTES FOR VALENCAY COMMEMORATION – 2017 Lieutenant Andrée Borrel, First Aid Nursing Yeomanry Andrée Raymonde Borrel was born in Paris on 18 November 1919 to a working-class family living in the suburb of Bécon-les-Bruyeres. She grew up with a love of the outdoors and a passion for hiking, climbing and cycling. Leaving school at 14 she worked firstly for a milliner then as an assistant in boulangeries. After the outbreak of war in 1939 she left to accompany her widowed mother to Toulon. In October she volunteered for the ‘Association des Dames de France’ training as a nurse. In January 1940 she went to Nîmes to care for wounded soldiers. After the fall of France she was unwilling to accept her country’s defeat and joined the Resistance, being drawn into the ‘Pat’ line assisting evaders’ escape to Spain. In late 1941 the line was betrayed and she escaped to Portugal. There she worked for the British Embassy until a flight to England was arranged in April 1942. After being cleared through the Royal Victoria Patriotic School she offered her services to De Gaulle’s HQ but was rejected after refusing to divulge details of the ‘Pat’ line. She was readily accepted by SOE’s F Section, not least because of her knowledge of conditions in France and her resistance experience. Given a commission in the FANY, she joined the first course for female agents in May 1942. After one failed attempt, Andrée (code name ‘Denise’) was dropped into France on the night of 24/25 September 1942 together with Lise de Baissac (‘Odile’), landing at Boisrenard near the village of Crouy-sur-Cosson. -

Publications

Anthony Lewis Brooks Associate Professor Department of Architecture, Design and Media Technology The Technical Faculty of IT and Design Section for Media Technology - Campus Aalborg Human Machine Interaction The Center for Applied Game Research Postal address: Rendsburggade 14 5-454 9000 Aalborg Denmark Postal address: Rendsburggade 14 5-454 9000 Aalborg Denmark Email: [email protected] Phone: 9940 9940 Mobile: 0045 2130 3015 Fax: 9940 7710 Web: http://personprofil.aau.dk/profil/103302, http://personprofil.aau.dk/profil/103302, http://personprofil.aau.dk/profil/103302 Web address: http://personprofil.aau.dk/profil/103302 Publications Leonardo Journal LABS top-ranked thesis abstracts of 2021 on intersections between art, science and technology: LABS ID: 4247 Brooks, Anthony "SOUNDSCAPES: THE EVOLUTION OF A CONCEPT, APPARATUS AND METHOD WHERE LUDIC ENGAGEMENT IN VIRTUAL INTERACTIVE SPACE IS A SUPPLEMENTAL TOOL FOR THERAPEUTIC MOTIVATION." PhD , Sunderland, UK, 2011 Brooks, A. L., 24 Sep 2021, 1 p. Online : Leonardo Electronic Almanac. Innovative and Assistive Technologies in Rehabilitation ‐ Keynote (60) ‐ Virtual Reality Rehabilitation in Moving Societies, September 7, 2021, 12:30 ‐ 13:30 Virtual Reality Rehabilitation in Moving Societies Brooks, A. L., 7 Sep 2021. The Zone of Optimised Motivation (ZOOM) Brooks, A. L., 19 Jul 2021, Digital Learning and Collaborative Practices: Lessons from Inclusive and Empowering Participation with Emerging Technologies. Brooks, E., Dau, S. & Selander, S. (eds.). 1 ed. Routledge, Vol. 1. Design, Learning,and Innovation Brooks, E. (ed.), Brooks, A. L. (ed.), Sylla, C. M. (ed.) & Møller, A. K. (ed.), 1 Jul 2021, (Lecture Notes of the Institute for Computer Sciences, Social Informatics and Telecommunications Engineering, Vol. -

EAI Endorsed Transactions on Creative Technologies

EAI Endorsed Transactions on Creative Technologies Editor-in-Chief Matei Mancas, University of Mons, Belgium Matei MANCAS has an Audiovisual Systems and Networks engineering degree (Ir.) from ESIGETEL Engineering School, France, and a MSc. degree in Information Processing from the University of Paris XI (Orsay). He holds a PhD in applied sciences from the Engineering Faculty of Mons (FPMs), Belgium since 2007. He made several research visits abroad as in La Sapienza University in Rome, Italy and IRISA-INRIA in Rennes, France. He is now a senior researcher and project leader at the Numediart Institute of the University of Mons, the institute of new media arts technologies where he acquired several years of experience with different projects involving together engineers, artists and people from creative industries. Matei is the organizer of several meetings of EU IP and COST projects and TPC and PC member of several conferences. He is also a member of the Management and Steering Committee of a COST Action and he is a representative of the researchers in the Board of Directors of the University of Mons. Matei’s research is about Smart Rooms and more precisely the analysis and modeling of human attention with applications to creative industries like TV, web and advertising. Special Issue Editor Manik Sharma Editorial Board Thierry Dutoit, University of Mons, Belgium Albert Ali Salah, Bogazici University, Turkey Pieter Jan Maes, McGill University, Canada Christophe d'Alessandro, LIMSI-CNRS, France Christian Jacquemin, LIMSI-CNRS, France Anton -

Aalborg Universitet INFORMATION SOCIETY EVOLUTION and EFFECTS Brooks, Anthony Lewis

Aalborg Universitet INFORMATION SOCIETY EVOLUTION AND EFFECTS Brooks, Anthony Lewis Published in: Proceedings 14th INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE e-Society 2016 Publication date: 2016 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication from Aalborg University Citation for published version (APA): Brooks, A. L. (2016). INFORMATION SOCIETY EVOLUTION AND EFFECTS: Keynote Lecture. In P. K. Kommers, & P. Isaías (Eds.), Proceedings 14th INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE e-Society 2016 (Vol. 14, pp. XV-XV). Portugal: International Association for Development, IADIS. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. ? Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. ? You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain ? You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us at [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from vbn.aau.dk on: April 30, 2017 14th INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE e-Society 2016 i ii PROCEEDINGS OF THE 14th INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE e-Society 2016 VILAMOURA, ALGARVE, PORTUGAL APRIL 9-11, 2016 Organised by Official Carrier iii Copyright 2016 IADIS Press All rights reserved This work is subject to copyright.