Angles Are Inherently Neither Length Ratios Nor Dimensionless

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI)

Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) m kg s cd SI mol K A NIST Special Publication 811 2008 Edition Ambler Thompson and Barry N. Taylor NIST Special Publication 811 2008 Edition Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) Ambler Thompson Technology Services and Barry N. Taylor Physics Laboratory National Institute of Standards and Technology Gaithersburg, MD 20899 (Supersedes NIST Special Publication 811, 1995 Edition, April 1995) March 2008 U.S. Department of Commerce Carlos M. Gutierrez, Secretary National Institute of Standards and Technology James M. Turner, Acting Director National Institute of Standards and Technology Special Publication 811, 2008 Edition (Supersedes NIST Special Publication 811, April 1995 Edition) Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol. Spec. Publ. 811, 2008 Ed., 85 pages (March 2008; 2nd printing November 2008) CODEN: NSPUE3 Note on 2nd printing: This 2nd printing dated November 2008 of NIST SP811 corrects a number of minor typographical errors present in the 1st printing dated March 2008. Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) Preface The International System of Units, universally abbreviated SI (from the French Le Système International d’Unités), is the modern metric system of measurement. Long the dominant measurement system used in science, the SI is becoming the dominant measurement system used in international commerce. The Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of August 1988 [Public Law (PL) 100-418] changed the name of the National Bureau of Standards (NBS) to the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and gave to NIST the added task of helping U.S. -

4.1 – Radian and Degree Measure

4.1 { Radian and Degree Measure Accelerated Pre-Calculus Mr. Niedert Accelerated Pre-Calculus 4.1 { Radian and Degree Measure Mr. Niedert 1 / 27 2 Radian Measure 3 Degree Measure 4 Applications 4.1 { Radian and Degree Measure 1 Angles Accelerated Pre-Calculus 4.1 { Radian and Degree Measure Mr. Niedert 2 / 27 3 Degree Measure 4 Applications 4.1 { Radian and Degree Measure 1 Angles 2 Radian Measure Accelerated Pre-Calculus 4.1 { Radian and Degree Measure Mr. Niedert 2 / 27 4 Applications 4.1 { Radian and Degree Measure 1 Angles 2 Radian Measure 3 Degree Measure Accelerated Pre-Calculus 4.1 { Radian and Degree Measure Mr. Niedert 2 / 27 4.1 { Radian and Degree Measure 1 Angles 2 Radian Measure 3 Degree Measure 4 Applications Accelerated Pre-Calculus 4.1 { Radian and Degree Measure Mr. Niedert 2 / 27 The starting position of the ray is the initial side of the angle. The position after the rotation is the terminal side of the angle. The vertex of the angle is the endpoint of the ray. Angles An angle is determine by rotating a ray about it endpoint. Accelerated Pre-Calculus 4.1 { Radian and Degree Measure Mr. Niedert 3 / 27 The position after the rotation is the terminal side of the angle. The vertex of the angle is the endpoint of the ray. Angles An angle is determine by rotating a ray about it endpoint. The starting position of the ray is the initial side of the angle. Accelerated Pre-Calculus 4.1 { Radian and Degree Measure Mr. Niedert 3 / 27 The vertex of the angle is the endpoint of the ray. -

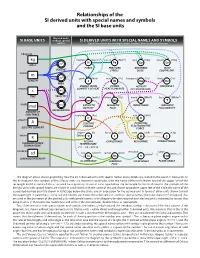

Relationships of the SI Derived Units with Special Names and Symbols and the SI Base Units

Relationships of the SI derived units with special names and symbols and the SI base units Derived units SI BASE UNITS without special SI DERIVED UNITS WITH SPECIAL NAMES AND SYMBOLS names Solid lines indicate multiplication, broken lines indicate division kilogram kg newton (kg·m/s2) pascal (N/m2) gray (J/kg) sievert (J/kg) 3 N Pa Gy Sv MASS m FORCE PRESSURE, ABSORBED DOSE VOLUME STRESS DOSE EQUIVALENT meter m 2 m joule (N·m) watt (J/s) becquerel (1/s) hertz (1/s) LENGTH J W Bq Hz AREA ENERGY, WORK, POWER, ACTIVITY FREQUENCY second QUANTITY OF HEAT HEAT FLOW RATE (OF A RADIONUCLIDE) s m/s TIME VELOCITY katal (mol/s) weber (V·s) henry (Wb/A) tesla (Wb/m2) kat Wb H T 2 mole m/s CATALYTIC MAGNETIC INDUCTANCE MAGNETIC mol ACTIVITY FLUX FLUX DENSITY ACCELERATION AMOUNT OF SUBSTANCE coulomb (A·s) volt (W/A) C V ampere A ELECTRIC POTENTIAL, CHARGE ELECTROMOTIVE ELECTRIC CURRENT FORCE degree (K) farad (C/V) ohm (V/A) siemens (1/W) kelvin Celsius °C F W S K CELSIUS CAPACITANCE RESISTANCE CONDUCTANCE THERMODYNAMIC TEMPERATURE TEMPERATURE t/°C = T /K – 273.15 candela 2 steradian radian cd lux (lm/m ) lumen (cd·sr) 2 2 (m/m = 1) lx lm sr (m /m = 1) rad LUMINOUS INTENSITY ILLUMINANCE LUMINOUS SOLID ANGLE PLANE ANGLE FLUX The diagram above shows graphically how the 22 SI derived units with special names and symbols are related to the seven SI base units. In the first column, the symbols of the SI base units are shown in rectangles, with the name of the unit shown toward the upper left of the rectangle and the name of the associated base quantity shown in italic type below the rectangle. -

Draft 9Th Edition of the SI Brochure

—————————————————————————— Bureau International des Poids et Mesures The International System of Units (SI) 9th edition 2019 —————————————————— 2 ▪ Draft of the ninth SI Brochure, 5 February 2018 The BIPM and the Metre Convention The International Bureau of Weights and Measures (BIPM) was set up by the Metre As of 20 May 2019, fifty Convention signed in Paris on 20 May 1875 by seventeen States during the final session of nine States were Members of this Convention: the diplomatic Conference of the Metre. This Convention was amended in 1921. Argentina, Australia, 2 Austria, Belgium, Brazil, The BIPM has its headquarters near Paris, in the grounds (43 520 m ) of the Pavillon de Bulgaria, Canada, Chile, Breteuil (Parc de Saint-Cloud) placed at its disposal by the French Government; its upkeep China, Colombia, Croatia, is financed jointly by the Member States of the Metre Convention. Czech Republic, Denmark, Egypt, Finland, The task of the BIPM is to ensure worldwide unification of measurements; its function is France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, India, Indonesia, thus to: Iran (Islamic Rep. of), • establish fundamental standards and scales for the measurement of the principal physical Iraq, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Kazakhstan, quantities and maintain the international prototypes; Kenya, Korea (Republic • carry out comparisons of national and international standards; of), Lithuania, Malaysia, • ensure the coordination of corresponding measurement techniques; Mexico, Montenegro, Netherlands, New • carry out and coordinate measurements of the fundamental physical constants relevant Zealand, Norway, to these activities. Pakistan, Poland, Portugal, Romania, The BIPM operates under the exclusive supervision of the International Committee for Russian Federation, Saudi Weights and Measures (CIPM) which itself comes under the authority of the General Arabia, Serbia, Singapore, Slovakia, Slovenia, South Conference on Weights and Measures (CGPM) and reports to it on the work accomplished Africa, Spain, Sweden, by the BIPM. -

1.4.3 SI Derived Units with Special Names and Symbols

1.4.3 SI derived units with special names and symbols Physical quantity Name of Symbol for Expression in terms SI unit SI unit of SI base units frequency1 hertz Hz s-1 force newton N m kg s-2 pressure, stress pascal Pa N m-2 = m-1 kg s-2 energy, work, heat joule J N m = m2 kg s-2 power, radiant flux watt W J s-1 = m2 kg s-3 electric charge coulomb C A s electric potential, volt V J C-1 = m2 kg s-3 A-1 electromotive force electric resistance ohm Ω V A-1 = m2 kg s-3 A-2 electric conductance siemens S Ω-1 = m-2 kg-1 s3 A2 electric capacitance farad F C V-1 = m-2 kg-1 s4 A2 magnetic flux density tesla T V s m-2 = kg s-2 A-1 magnetic flux weber Wb V s = m2 kg s-2 A-1 inductance henry H V A-1 s = m2 kg s-2 A-2 Celsius temperature2 degree Celsius °C K luminous flux lumen lm cd sr illuminance lux lx cd sr m-2 (1) For radial (angular) frequency and for angular velocity the unit rad s-1, or simply s-1, should be used, and this may not be simplified to Hz. The unit Hz should be used only for frequency in the sense of cycles per second. (2) The Celsius temperature θ is defined by the equation θ/°C = T/K - 273.15 The SI unit of Celsius temperature is the degree Celsius, °C, which is equal to the Kelvin, K. -

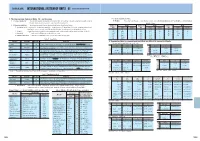

International System of Units (Si)

[TECHNICAL DATA] INTERNATIONAL SYSTEM OF UNITS( SI) Excerpts from JIS Z 8203( 1985) 1. The International System of Units( SI) and its usage 1-3. Integer exponents of SI units 1-1. Scope of application This standard specifies the International System of Units( SI) and how to use units under the SI system, as well as (1) Prefixes The multiples, prefix names, and prefix symbols that compose the integer exponents of 10 for SI units are shown in Table 4. the units which are or may be used in conjunction with SI system units. Table 4. Prefixes 1 2. Terms and definitions The terminology used in this standard and the definitions thereof are as follows. - Multiple of Prefix Multiple of Prefix Multiple of Prefix (1) International System of Units( SI) A consistent system of units adopted and recommended by the International Committee on Weights and Measures. It contains base units and supplementary units, units unit Name Symbol unit Name Symbol unit Name Symbol derived from them, and their integer exponents to the 10th power. SI is the abbreviation of System International d'Unites( International System of Units). 1018 Exa E 102 Hecto h 10−9 Nano n (2) SI units A general term used to describe base units, supplementary units, and derived units under the International System of Units( SI). 1015 Peta P 10 Deca da 10−12 Pico p (3) Base units The units shown in Table 1 are considered the base units. 1012 Tera T 10−1 Deci d 10−15 Femto f (4) Supplementary units The units shown in Table 2 below are considered the supplementary units. -

Radian Measurement

Radian Measurement: What It Is, and How to Calculate It More Easily Using τ Instead of π by Stanley M. Max Adjunct Faculty Towson University Radian measurement In trigonometry, pre-calculus, and higher mathematics, angles are usually measured not in degrees but in radians. Why? To some extent the answer to that question requires studying first- semester calculus. Even at the level of trigonometry and pre-calculus, however, we can partially answer the question. Using radians offers a more efficient system for measuring angles involving more than one rotation. Quick, how many degrees does an angle have that spins around eight-and-a-half times? By using radians, we shall see how speedily you can find the answer. So then, what is a radian? Mathematically, a radian is defined by the following formula: s rad , where the symbol means “is defined as” (1.01) r In this formula, represents the angle being measured, s represents arc length, r represents radius, and rad means radians. Look at the following diagram: Figure 1: Arc length (s) = radius (r) when θ = 1 rad. Graphic created using Mathematica, v. 8. This picture shows that the angle is measured as the ratio of the arc length (s) to the radius (r) of an imaginary circle, and if the angular measurement is made in that fashion, then the measurement is made in radians. Now suppose that s equals r. In that case, equals one radian. In other words, one radian is the measurement of an angle that is opened just wide enough for the following to happen: If the angle is located at the center of a circle, then the length of the arc that the angle intercepts on the circumference will exactly equal the length of the radius of the circle. -

The International System of Units (SI) - Conversion Factors For

NIST Special Publication 1038 The International System of Units (SI) – Conversion Factors for General Use Kenneth Butcher Linda Crown Elizabeth J. Gentry Weights and Measures Division Technology Services NIST Special Publication 1038 The International System of Units (SI) - Conversion Factors for General Use Editors: Kenneth S. Butcher Linda D. Crown Elizabeth J. Gentry Weights and Measures Division Carol Hockert, Chief Weights and Measures Division Technology Services National Institute of Standards and Technology May 2006 U.S. Department of Commerce Carlo M. Gutierrez, Secretary Technology Administration Robert Cresanti, Under Secretary of Commerce for Technology National Institute of Standards and Technology William Jeffrey, Director Certain commercial entities, equipment, or materials may be identified in this document in order to describe an experimental procedure or concept adequately. Such identification is not intended to imply recommendation or endorsement by the National Institute of Standards and Technology, nor is it intended to imply that the entities, materials, or equipment are necessarily the best available for the purpose. National Institute of Standards and Technology Special Publications 1038 Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol. Spec. Pub. 1038, 24 pages (May 2006) Available through NIST Weights and Measures Division STOP 2600 Gaithersburg, MD 20899-2600 Phone: (301) 975-4004 — Fax: (301) 926-0647 Internet: www.nist.gov/owm or www.nist.gov/metric TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD.................................................................................................................................................................v -

MATH 1330 - Section 4.2 - Radians, Arc Length, and Area of a Sector

Page 1 of 6 MATH 1330 - Section 4.2 - Radians, Arc Length, and Area of a Sector Two rays that have a common endpoint (vertex) form an angle. One ray is the initial side and the other is the terminal side. We typically will draw angles in the coordinate plane with the initial side along the positive 푥-axis. A Terminal side Vertex B Initial Side C ∠퐵, ∠퐴퐵퐶, ∠퐶퐵퐴, and 휃 are all notations for this angle. When using the notation ∠퐴퐵퐶 and ∠퐶퐵퐴 the vertex is always the middle letter. We measure angles in two different ways, both of which rely on the idea of a complete revolution in a circle. The first is degree measure. In this system of angle measure one 1 complete revolution is 360°. Therefore, one degree is th of a circle. 360 The second method is called radian measure. One complete revolution is 2. The problems in this section are worked in radians. When there is no symbol next to an angle measure, radians are assumed. The Radian Measure of an Angle Place the vertex of the angle at the center of a circle (central angle) of radius 푟. Let 푠 denote the length of the arc intercepted by the angle. The radian measure 휃 of the angle is the ratio of the arc length 푠 to the radius 푟. In symbols, 푠 휃 = 푟 In this definition, it is assumed that 푠 and 푟 have the same linear units. s r If the central angle 휃 and radius 푟 are given we can use the same formula to calculate the arc length 푠 by applying the formula: 푠 = 푟휃. -

29 Applications of Radian Measure

- 29 Applications of Radian Measure This section focuses on the use of Radians to measure angles and the appli- cations of this, including areas and arc-lengths. By the end of this section, you should have the following skills: • An understanding of definition of a Radian. • Convert angles between degrees and radians. • An understanding of the definition of a sector and segment. • Calculate the arc length and area of a circle sector and apply this to real life examples. 29.1 Radians Radians are often used instead of degrees when measuring angles. In degrees a complete revolution of a circle is 360◦, however in radians it is 2π. If an arc of a circle is drawn such that the radius is the same length as the arc, the angle created is 1 Radian (as shown below). 1 29.2 Converting Between Degrees and Radians • Degrees to Radians: π Radians = × Degrees 180 • Radians to Degrees: 180 Degrees = × Radians π Example 1 1. Convert the following angles from degrees to radians. (a) 140◦ (b) 20◦ (c) 270◦ 2. Convert the following angles from radians to degrees. 2 (a) 3 π (b) 3π 16 (c) 9 π Solution: 1. (a) π 7 140◦ = × 140 = π Rad 180 9 (b) π 1 20◦ = × 20 = π Rad 180 9 (c) π 3 270◦ = × 270 = π Rad 180 2 2. (a) 2 180 2 180 × 2 π = × π = = 120◦ 3 π 3 3 2 (b) 180 3π = × 3π = 180 × 3 = 540◦ π (c) 16 180 16 180 × 16 π = × π = = 320◦ 9 π 9 9 29.3 Arc Length of a Circle The length of an arc is just a portion of the circumference, which we know to be 2πr, where r is the radius of the circle. -

Mobius Units Help SI/Metric Units (Accept Prefixes)

Mobius Units Help The Unit column of the following tables display all of the units that are recognized by the system. You can use either the units themselves, or combinations of these units, for example kJ/mol, kg*m^2, or m/s/s. The system accepts equivalent answers with different units as long as both units are accepted in the system. That is, if the answer is 120 cm, then 1.2 m or 1200 mm will also be accepted as correct. SI/Metric Units (Accept Prefixes) The units in this section can each be prefixed with one of the accepted SI prefixes below. SI Prefixes Base Units Prefix Factor Name Unit Definition Name Y 10^24 yotta m meter Z 10^21 zetta s second E 10^18 exa kg kilogram P 10^15 peta A amp T 10^12 tera K kelvin G 10^9 giga M 10^6 mega Derived SI Units k 10^3 kilo Unit Definition Name 6.02214199 * h 10^2 hecto mol mole da 10^1 deca 10^23 d 10^-1 deci rad 1 radian c 10^-2 centi sr 1 steradian m 10^-3 milli Hz 1/s hertz u 10^-6 micro N kg m/s^2 newton n 10^-9 nano Pa N/m^2 pascal p 10^-12 pico J N m joule f 10^-15 femto W J/s watt a 10^-18 atto C A s coulomb z 10^-21 zepto V J/C volt y 10^-24 yocto F C/V farad ohm V/A ohm CGS Units S A/V siemens Unit Definition Name Wb V s weber erg 10^-7 J erg T Wb/m^2 tesla dyn 10^-5 N dyne H Wb/A henry P 0.1 Pa*s poise lm cd sr lumen St cm^2/s stokes lx lm/m^2 lux sb cd/cm^2 stilb Bq s^-1 becquerel ph 10^4 lx phot Gy J/kg gray Gal cm/s^2 gal Sv J/kg sievert Mx 10^-8 Wb maxwell kat mol/s katal G 10^-4 T gauss Metric Units oersted Oe (10^3/4/Pi) A/m (rationalized) Unit Definition Name L m^3/1000 liter M mol/L molar eV J*1.602E-19 electron volt SI/Metric Units (No Prefixes) These units, and alternative ways of writing units, do not accept SI prefixes. -

ECE 3793 Matlab Project 4 Solution

ECE 3793 Matlab Project 4 Solution Spring 2017 Dr. Havlicek PART I: the DFT 1. Matlab code: %-------------------------------------------------------- % P1 % % - Create and plot the signal x_1[n] as a function of n. % - Compute the DFT X_1[k]. Plot the magnitude and phase % as functions of k. % - Plot the DFT magnitude as a function of the matlab % array index. % - Plot the DFT magnitude as a function of the discrete % radian frequency w. % - Compute and plot the IDFT. % n = 0:7; % time variable x1n = [0 1 1 1 1 1 0 0]; % our 8-point signal X1k = fft(x1n); % compute the DFT X1kmag = abs(X1k); % magnitude of the DFT X1karg = angle(X1k); % phase of the DFT % plot the signal figure(1); stem(n,x1n); axis([0 7 0 1.5]); title('Original Signal'); xlabel('n'); ylabel('x_1[n]'); % plot DFT magnitude and phase as functions of k k = 0:7; % frequency index figure(2); stem(k,X1kmag); ylim([0 6]); title('DFT Magnitude'); xlabel('k'); ylabel('|X_1[k]|'); figure(3); stem(k,X1karg); title('DFT Phase'); xlabel('k'); ylabel('arg(X_1[k])'); 1 % plot DFT magnitude as a function of Matlab index Matlab_idx = [1:8]; % Matlab index figure(4); stem(Matlab_idx,X1kmag); ylim([0 6]); title('DFT Magnitude'); xlabel('Matlab index'); ylabel('|X_1[index]|'); % plot DFT magnitude as a function of discrete frequency % (radians per sample) w = [0:2*pi/8:7*2*pi/8]; % discrete frequency figure(5); stem(w,X1kmag); ylim([0 6]); title('DFT Magnitude'); ylim([0 6]); xlabel('discrete radian frequency \omega'); ylabel('|X_1[\omega]|'); % Compute and plot the IDFT x2n = ifft(X1k); figure(6); stem(n,x2n); axis([0 7 0 1.5]); title('IDFT'); xlabel('n'); ylabel('IDFT'); Original Signal 1.5 1 [n] 1 x 0.5 0 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 n 2 DFT Magnitude 6 5 4 [k]| 1 3 |X 2 1 0 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 k DFT Phase 4 3 2 1 [k]) 1 arg(X 0 −1 −2 −3 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 k 3 DFT Magnitude 6 5 4 3 [index]| 1 |X 2 1 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Matlab index DFT Magnitude 6 5 4 ]| ω [ 1 3 |X 2 1 0 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 discrete radian frequency ω 4 IDFT 1.5 1 IDFT 0.5 0 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 n 2.