Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Road & Track Magazine Records

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8j38wwz No online items Guide to the Road & Track Magazine Records M1919 David Krah, Beaudry Allen, Kendra Tsai, Gurudarshan Khalsa Department of Special Collections and University Archives 2015 ; revised 2017 Green Library 557 Escondido Mall Stanford 94305-6064 [email protected] URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc Guide to the Road & Track M1919 1 Magazine Records M1919 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: Department of Special Collections and University Archives Title: Road & Track Magazine records creator: Road & Track magazine Identifier/Call Number: M1919 Physical Description: 485 Linear Feet(1162 containers) Date (inclusive): circa 1920-2012 Language of Material: The materials are primarily in English with small amounts of material in German, French and Italian and other languages. Special Collections and University Archives materials are stored offsite and must be paged 36 hours in advance. Abstract: The records of Road & Track magazine consist primarily of subject files, arranged by make and model of vehicle, as well as material on performance and comparison testing and racing. Conditions Governing Use While Special Collections is the owner of the physical and digital items, permission to examine collection materials is not an authorization to publish. These materials are made available for use in research, teaching, and private study. Any transmission or reproduction beyond that allowed by fair use requires permission from the owners of rights, heir(s) or assigns. Preferred Citation [identification of item], Road & Track Magazine records (M1919). Dept. of Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, Calif. Conditions Governing Access Open for research. Note that material must be requested at least 36 hours in advance of intended use. -

Imlay + Horn the Politics of Industrial Collaboration During WWII Excerpts

The Politics of Industrial Collaboration during World War II Ford France^ Vichy and Nazi Germany Talbot Imlay Universite Laval and Martin Horn McMaster University M Cambridge UNIVERSITY PRESS i I 1 X List of abbreviations RkBfV Reichskommissariat fur die Behandlung feindlichen Vermogens RWM Reichswirtschaftsministerium SAF Societe anonyme frangaise Introduction SaSC Sachsisches Staatsarchiv, Chemnitz SHGN Service historique de la gendarmerie nationale, Vincennes SHGR Societe d’histoire du groupe Renault, Boulogne-Billancourt TNA The National Archives, Kew Gardens ZASt Zentralauftragsstelle In October 1944, two months after the liberation of Paris, Fran9ois Lehideux was arrested by the French police and charged with ‘intelligence avec I’ennemi’ - with having collaborated with the Germans during the Occupation. A product of the elite Ecole libre des sciences politiques with considerable experience in finance and industry, Lehideux had been at the centre of the Vichy regime’s economic policies, serving as commissioner for unemployment, delegate-general for national (industrial) equipment, and state secretary for industrial production.^ In each of these positions, he worked closely with the German occupation authorities. But it was Lehideux’s activities as the director of the professional organization for the French automobile industry, the Comite d’organisation de I’automobile et du cycle (GOA), created in September 1940, that appeared the most damning. From 1940 to 1944, the automobile industry had worked over whelmingly for the Germans, delivering some 85 per cent of its produc tion to them. Collectively, French automobile companies had made a major contribution to Germany’s war effort, and as the industry’s political chief, Lehideux was deemed to be directly responsible. -

Form 10 Visteon Corporation

Table of Contents As filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission on May 19, 2000 File No. 001-15827 SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 AMENDMENT NO. 1 TO FORM 10 GENERAL FORM FOR REGISTRATION OF SECURITIES PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(b) OR 12(g) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 VISTEON CORPORATION (Exact Name of Registrant as Specified in Its Charter) DELAWARE 38-3519512 (State or Other Jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer Incorporation or Organization) Identification No.) Fairlane Plaza North 10th Floor 290 Town Center Drive Dearborn, Michigan 48126 (Address of Principal Executive Offices) (Zip Code) (800) VISTEON (Registrant’s telephone number, including area code) Securities to be registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of each class Name of each exchange on which to be so registered each class is to be registered Common Stock, par value $1.00 per share The New York Stock Exchange Securities to be registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None Table of Contents INFORMATION REQUIRED IN REGISTRATION STATEMENT CROSS-REFERENCE SHEET BETWEEN INFORMATION STATEMENT AND ITEMS OF FORM 10 Item 1. Business The information required by this item is contained under the sections “Summary,” “Risk Factors,” “Business” and “Relationship with Ford” of the Information Statement attached hereto. Those sections are incorporated herein by reference. Item 2. Financial Information The information required by this item is contained under the sections “Summary,” “Capitalization,” “Unaudited Pro Forma Condensed Consolidated Financial Statements,” “Selected Consolidated Financial Data” and “Management’s Discussion and Analysis of Financial Condition and Results of Operations” of the Information Statement. -

Karl E. Ludvigsen Papers, 1905-2011. Archival Collection 26

Karl E. Ludvigsen papers, 1905-2011. Archival Collection 26 Karl E. Ludvigsen papers, 1905-2011. Archival Collection 26 Miles Collier Collections Page 1 of 203 Karl E. Ludvigsen papers, 1905-2011. Archival Collection 26 Title: Karl E. Ludvigsen papers, 1905-2011. Creator: Ludvigsen, Karl E. Call Number: Archival Collection 26 Quantity: 931 cubic feet (514 flat archival boxes, 98 clamshell boxes, 29 filing cabinets, 18 record center cartons, 15 glass plate boxes, 8 oversize boxes). Abstract: The Karl E. Ludvigsen papers 1905-2011 contain his extensive research files, photographs, and prints on a wide variety of automotive topics. The papers reflect the complexity and breadth of Ludvigsen’s work as an author, researcher, and consultant. Approximately 70,000 of his photographic negatives have been digitized and are available on the Revs Digital Library. Thousands of undigitized prints in several series are also available but the copyright of the prints is unclear for many of the images. Ludvigsen’s research files are divided into two series: Subjects and Marques, each focusing on technical aspects, and were clipped or copied from newspapers, trade publications, and manufacturer’s literature, but there are occasional blueprints and photographs. Some of the files include Ludvigsen’s consulting research and the records of his Ludvigsen Library. Scope and Content Note: The Karl E. Ludvigsen papers are organized into eight series. The series largely reflects Ludvigsen’s original filing structure for paper and photographic materials. Series 1. Subject Files [11 filing cabinets and 18 record center cartons] The Subject Files contain documents compiled by Ludvigsen on a wide variety of automotive topics, and are in general alphabetical order. -

U Nder the N Azi R Egime Azi Azi R R Egime Egime a a Bout Bout

F R F R U U ESEARCH ESEARCH ORD ORD NDER THE NDER THE R ESEARCH F INDINGS A BOUT - W - - W - F ORD - WERKE F F INDINGS INDINGS N N ERKE ERKE U NDER THE N AZI R EGIME AZI AZI R R EGIME EGIME A A BOUT BOUT R ESEARCH F INDINGS A BOUT F ORD - WERKE U NDER THE N AZI R EGIME Published by Published by Ford Motor Ford Motor Company Company C ONTACT I NFORMATION R ESEARCH R ESOURCES More than 30 archival repositories were At Henry Ford Museum & Greenfield Researchers planning to use primary Media Contacts: searched during the course of this project. Village, the documents and the database will materials are requested to make an Appendix H, Glossary of Repository Sources be available to the public at the Benson Ford appointment before visiting. The Research Tom Hoyt and Bibliography, lists the major archival Research Center: Center Office and Reading Room are open 1.313.323.8143 sources. Monday through Friday, 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. [email protected] Benson Ford Research Center Descriptions of the documents collected Henry Ford Museum & Greenfield Village Henry Ford Museum & Greenfield Village have been entered into a searchable database. 20900 Oakwood Boulevard is a member of OCLC (Online Computer The documents and the database are being P.O. Box 1970 Library Center) and The Library Network Niel Golightly donated to Henry Ford Museum & Dearborn, Michigan 48121-1970 (TLN). 49.0221.901057 Greenfield Village, an independent, nonprofit U.S.A. [email protected] educational institution unaffiliated with Ford tel: 1.313.982.6070 Note:The Henry Ford Museum Reading Room will be Motor Company. -

980470 Life Cycle Assessment of a Transmission Case: Magnesium Vs

Downloaded from SAE International by University of Michigan, Tuesday, April 02, 2019 SAE TECHNICAL PAPER SERIES 980470 Life Cycle Assessment of a Transmission Case: Magnesium vs. Aluminum Peter Reppe and Gregory Keoleian University of Michigan Rebecca Messick and Mia Costic Ford Motor Company International Congress and Exposition Detroit, Michigan February 23-26, 1998 400 Commonwealth Drive, Warrendale, PA 15096-0001 U.S.A. Tel: (724) 776-4841 Fax: (724) 776-5760 Downloaded from SAE International by University of Michigan, Tuesday, April 02, 2019 The appearance of this ISSN code at the bottom of this page indicates SAE’s consent that copies of the paper may be made for personal or internal use of specific clients. This consent is given on the condition, however, that the copier pay a $7.00 per article copy fee through the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc. Operations Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923 for copying beyond that permitted by Sec- tions 107 or 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law. This consent does not extend to other kinds of copying such as copying for general distribution, for advertising or promotional purposes, for creating new collective works, or for resale. SAE routinely stocks printed papers for a period of three years following date of publication. Direct your orders to SAE Customer Sales and Satisfaction Department. Quantity reprint rates can be obtained from the Customer Sales and Satisfaction Department. To request permission to reprint a technical paper or permission to use copyrighted SAE publications in other works, contact the SAE Publications Group. All SAE papers, standards, and selected books are abstracted and indexed in the Global Mobility Database No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form, in an electronic retrieval system or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. -

Hitler's Biggest Allies in World War II Were Ford, General Motors &

Cars & Nazis article Hitler’s biggest allies in World War II were Ford, General Motors & a special report by Clive Matthew-Wilson All content © The Dog & Lemon Guide 2010. All rights reserved N 1937, William E. Dodd, U.S. a tiny bunch of nutters raving on Mu- Ambassador to Germany, sent an nich street corners, Ford is believed to I urgent warning to the American have provided considerable amounts of government: finance to the fledgling party, enabling the Nazis to gain their stronghold on “A clique of U.S. industrialists is Germany. It is notable that even after hell-bent to bring a fascist state to sup- “A clique of U.S. the horrors of the Nazi era were exposed plant our democratic government and is following World War II, Ford never working closely with the fascist regimes industrialists denied financing Hitler. in Germany and Italy. ”1 is hell-bent By the mid-1930s General Motors Ford, General Motors and Standard to bring a was totally committed to large-scale Oil weren’t just the world’s leading auto- fascist state to war production in Germany, produc- motive suppliers, they were among the supplant our ing trucks, tanks & armoured cars. Its largest and wealthiest corporations on German subsidiary Adam-Opel manu- the planet. Greedy, ruthless and drunk democratic factured a host of effective military with Nazi ideology, they decided to help government equipment for the German military end democracy, first in Europe, then in throughout the war. And, while the America. and is working American Air Force used conventional closely with the piston engines, the German Air Force While their own country was at war fascist regimes was close to getting the world’s first with Germany, Ford, General Motors jet fighters, thanks almost entirely to and Standard Oil kept or expanded in Germany General Motors. -

H-Diplo Roundtable, Vol. XVII

2015 Roundtable Editors: Thomas Maddux and Diane H-Diplo Labrosse H-Diplo Roundtable Review Roundtable and Web Production Editor: George Fujii Volume XVII, No. 9 (2015) 7 December 2015 Introduction by Kenneth Mouré Talbot Imlay and Martin Horn. The Politics of Industrial Collaboration during World War II: Ford France, Vichy and Nazi Germany. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014. ISBN: 9781107016361 (hardback, $110.00). URL: http://www.tiny.cc/Roundtable-XVII-9 Contents Introduction by Kenneth Mouré, University of Alberta ....................................................................... 2 Review by Patrick Fridenson, Emeritus Professor of International Business History at the Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales (EHESS), Paris, France ................................................. 7 Review by Peter Hayes, Northwestern University ................................................................................ 17 Review by Ray Stokes, University of Glasgow ....................................................................................... 19 Author’s Response by Talbot Imlay, Université Laval, and Martin Horn, McMaster University ............................................................................................................................................................. 22 © 2015 The Authors. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 United States License. H-Diplo Roundtable Reviews, Vol. XVII, No. 9 (2015) Introduction by Kenneth Mouré, University of -

Ford Anti-Report

ct/54 -t COUNTERINFORMATION SERVICES - A TRANSNATIONALINSTITUTE AFFILIATE 90p The FordMotor Company Counterlnfonnation Services 9 PolandStreet. London Wl. 01439 3764 .\nti-ReportNo.20 \: : \\ .:r; CIS -.S .. - .':irireof journalistswho pub- ..:: .: : ,::t3tionnot coveredor collated r. ::.3 eslablishedmedia. It is their aim - .:.',3s:rsatethe majorsocial and econo- :''.. .:.:rriutionsthat governour daily ,..;: .. order that the basicfacts and :::-:u:t1L)nSbehind them be as rvidely .\- \\ii as possible.CIS is financedby ,..:s. subscriptions,donations and grants. Subscribe l-+.00UK, {,5.00overseas, for six issues. Special Discount for bulk orders. All rvailablefrom CIS,9 PolandStreet, LondonWl. (01-4393164). Distributedby Pluto Press,Unit 10. SpencerCourt, 7 ChalcotRoad, London \wl 8LH. rsBN0 903660l8 0 Designby JulianStapleton. Publishedby CounterInformation Services. Printed by the Russell PressLimited. -l-iGamble Street. Nor ringham NG7 4ET. Far right. Henry II ERRATUMPAGE 26 TableFiesta Costings Thefirst figure $1,215 should reaci $215 rI I ilry i I t i ri.,: ,i$ru,fufo;, q#ah r$ffi.€) s*b ;\*ffi ffi " ft&1;'l i;$ +:;,it ::lrLn:: ;,[ji:, =* i $ H' $,' Sr lU Popperfoto The Ford Motor Company is in the tionally by geography'and nationality. ary.and governmentwage freezes cited to business of making money out of car- Ford, on the other hand. benefitsirom justify their refusal.Tax incentivesand workers. To do this it mounts a constant its centralisedcontrol of manaqementsubsidiesabound as national govern- three-pronged attack: on wages, on strategy. ments competefor Ford's favours.Ford productivity levels, and on workers' flourishesin Europe while Europeancar attempts to organisethemselves. In Europe.lor example.the UK work- firms struggleto survive.The company's force is threatened*rth an embargoon ability to make record profits at the In order to extract greater productivity further UK investmentunless continental expenseof Europeanworkers and national (more work for the same pay) from its levels oi productivity are achieved. -

Automotive Aerodynamics & Thermal Management

BOOK & PAY THE LARGEST OEM REPRESENTATION IN A UNIQUE INTERACTIVE JOINT BY JUNE 31 FF AUTOMOTIVE AERODYNAMICS & THERMAL MANAGEMENT CONFERENCE & GET 40% O THE STANDARD BENEFIT FROM 2 CONFERENCES IN 1 EVENT! PRICE! VENUE: Radisson Blu Hotel Manchester Airport With featured experts, among others, from: AUTOMOTIVE AERODYNAMICS & THERMAL MANAGEMENT IΝΤΕ RNATIONAL FORUM 19-20 November 2019, Manchester, UK Organized by “All of the important people in this business are there. "The somewhat unconventional format of the con - It was a brilliant experience and a great chance to ference that focuses on personal interaction makes share your knowledge.” this a unique and worthwhile event.” Jan Jagrik, Škoda Auto Moni Islam, Audi AG "Highest rate of new contact development that I have “It’s amazing that there is such a high level of execu - ever experienced.” tives, directors and chief engineers at this confer - Dana Nicgorski, Robert Bosch LLC ence.” Amit Shah, ANSYS "An excellent venue to promote our solutions with the best audience that we can get. Fantastic event!” Ajith Narayanan, Altair Scientific Committee & Keynote Speakers: : s n o i s s e S s c i More than 200 companies from over 20 countries m a were represented in our past Automotive Aerodynamics n y & Τhermal Management Forums, among which: d Atsushi Ogawa Dr. Moni Islam Craig Rowberry Adrian Gaylard Dr. Sanjay Kumarasamy o r Head of Aerodynamics, Head of Aerodynamics Functional Manager Technical Specialist EGM - Global Aerodynamics • AstonMartin • Audi • Bentley Motors Limited • BMW • -

How the Ford Motor Company Became an Arsenal of Nazism

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Honors Program in History (Senior Honors Theses) Department of History May 2008 The Silent Partner: How the Ford Motor Company Became an Arsenal of Nazism Daniel Warsh University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/hist_honors Warsh, Daniel, "The Silent Partner: How the Ford Motor Company Became an Arsenal of Nazism" (2008). Honors Program in History (Senior Honors Theses). 17. https://repository.upenn.edu/hist_honors/17 A Senior Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Honors in History. Faculty Advisor: Walter Licht This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/hist_honors/17 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Silent Partner: How the Ford Motor Company Became an Arsenal of Nazism Abstract Corporate responsibility is a popular buzzword in the news today, but the concept itself is hardly novel. In response to a barrage of public criticism, the Ford Motor Company commissioned and published a study of its own activities immediately before and during WWII. The study explores the multifaceted and complicated relationship between the American parent company in Dearborn and the German subsidiary in Cologne. The report's findings, however, are largely inconclusive and in some cases, dangerously misleading. This thesis will seek to establish how, with the consent of Dearborn, the German Ford company became an arsenal for Hitler's march on Europe. This thesis will clarify these murky relationships, and picking up where the Ford internal investigation left off, place them within a framework of corporate accountability and complicity. -

One of the Most Original and Significant Ford Gt40s Produced Will Soon Go Under the Hammer

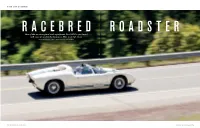

FORD GT40 ROADSTER RACEBRED ROADSTER One of the most original and significant Ford GT40s produced will soon go under the hammer. This is its life story WORDS David Burgess-Wise // PHOTOGRAPHY Pawel Litwinski 74 SEPTEMBER 2014 OCTANE OCTANE SEPTEMBER 2014 75 FORD GT40 ROADSTER Right GT/108 differed slightly from earlier GT40 prototypes, with a new nose developed by Len Bailey at FAV and high-set rear-pillar air intakes. It remains the sole survivor with this nose treatment. Engine is a Cobra-spec Ford 289 V8. ISTORY RECORDS that the Ford GT40 programme was Negotiations for a takeover had seemingly gone well, and the deal a prime example of the old adage ‘Don’t get mad, get was due to be announced on 23 May but, in his imperious way, Ferrari even’. In 1963, word had reached Ford headquarters in – who thought the deal had been sealed with a handshake and then Dearborn via Ford of Germany that Enzo Ferrari was found that the Ford lawyers were drawing up formal documents for anxious to sell his company. What could have been the signature – had called it off at the very last minute. In Dearborn in the most sensational takeover in Ford’s long history grew late 1980s I met a Ford-US public relations man who had set up a press from a beginning so insignificant that when, in the 1980s, I conference for 23 May to announce the deal, only to have to cancel it at Hinterviewed former Ford-Germany executive Robert Layton, the man 24 hours’ notice… who had set the ball rolling, he remembered nothing of the Ford-Ferrari Smarting from the rebuff, Henry Ford II and Lee Iacocca drew up negotiations, save that the chance to buy Ferrari was just one of hundreds plans to build a car to beat Ferrari where it hurt, at the Le Mans 24 of proposals made to Ford Germany at the time.