From Unsuitable Ally to Vital Parter: the Case of US-Korean Relations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North Korea Vs the United States

North Korea vs the United States Executive Summary A North Korean regular infantry division is the most likely type of division a US unit would face on the Korean peninsula. While the Korean People’s Army (KPA) fields armor and mechanized units, the number of regular infantry units far exceeds the other types (pg 3). KPA offensive operations include the heavy use of artillery with chemical munitions; a primary focus of attacks on combat support (CS), combat service support (CSS), and command and control (C2) units; and deep operations conducted by KPA special-purpose forces (SPF) (pgs 3–4, 11–16, 21–23). KPA defensive operations focus on the elimination of enemy armor through the heavy use of artillery; battalion, regiment, and division antitank kill zones; and the use of counterattack forces at all levels above battalion-sized units (pgs 16–19, 23–26). While US forces will face KPA conventional infantry to their front, KPA SPF will initiate offensive operations in the US/South Korean rear areas to create a “second front” (pgs 15–16). KPA regular forces and SPF will remain in place to conduct stay-behind annihilation ambushes on CS, CSS, and C2 units passing through the passed unit’s area of operations (pg 25). The KPA divisions are already prepared to fight US and Republic of Korea (ROK) forces today. The vehicles and equipment may be different in the future, but their tactics and techniques will be similar to those used today (pgs 10–26). Since 2003, the KPA has created seven divisions that are specialized to operate in urban and mountain terrain using irregular warfare techniques. -

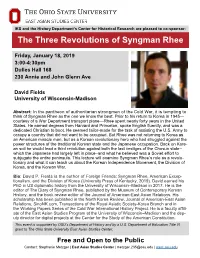

The Three Revolutions of Syngman Rhee

IKS and the History Department’s Center for Historical Research are pleased to co-sponsor: The Three Revolutions of Syngman Rhee Friday, January 18, 2019 3:00-4:30pm Dulles Hall 168 230 Annie and John Glenn Ave David Fields University of Wisconsin-Madison Abstract: In the pantheon of authoritarian strongmen of the Cold War, it is tempting to think of Syngman Rhee as the one we know the best. Prior to his return to Korea in 1945— courtesy of a War Department transport plane—Rhee spent nearly forty years in the United States. He earned degrees from Harvard and Princeton, spoke English fluently, and was a dedicated Christian to boot. He seemed tailor-made for the task of assisting the U.S. Army to occupy a country that did not want to be occupied. But Rhee was not returning to Korea as an American miracle man, but as a Korean revolutionary hero who had struggled against the power structures of the traditional Korean state and the Japanese occupation. Back on Kore- an soil he would lead a third revolution against both the last vestiges of the Chosun state– which the Japanese had largely left in place–and what he believed was a Soviet effort to subjugate the entire peninsula. This lecture will examine Syngman Rhee’s role as a revolu- tionary and what it can teach us about the Korean Independence Movement, the Division of Korea, and the Korean War. Bio: David P. Fields is the author of Foreign Friends: Syngman Rhee, American Excep- tionalism, and the Division of Korea (University Press of Kentucky, 2019). -

A Legal Study of the Korean War Howard S

The University of Akron IdeaExchange@UAkron Akron Law Review Akron Law Journals July 2015 How It All Started - And How It Ended: A Legal Study of the Korean War Howard S. Levie Please take a moment to share how this work helps you through this survey. Your feedback will be important as we plan further development of our repository. Follow this and additional works at: http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/akronlawreview Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Levie, Howard S. (2002) "How It All Started - And How It Ended: A Legal Study of the Korean War," Akron Law Review: Vol. 35 : Iss. 2 , Article 2. Available at: http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/akronlawreview/vol35/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Akron Law Journals at IdeaExchange@UAkron, the institutional repository of The nivU ersity of Akron in Akron, Ohio, USA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Akron Law Review by an authorized administrator of IdeaExchange@UAkron. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Levie: A Legal Study of the Korean War LEVIE1.DOC 3/26/02 12:29 PM HOW IT ALL STARTED - AND HOW IT ENDED: A LEGAL STUDY OF THE KOREAN WAR Howard S. Levie A. World War II Before taking up the basic subject of the discussion which follows, it would appear appropriate to ascertain just what events led to the creation of two such disparate independent nations as the Republic of Korea (hereinafter referred to as South Korea) and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (hereinafter referred to as North Korea) out of what had been a united territory for centuries, whether independent or as the possession of a more powerful neighbor, Japan — and the background of how the hostilities were initiated in Korea in June 1950. -

Military Authoritarian Regimes and Economic Development the ROK's Economic Take-Off Under Park Chung Hee

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Calhoun, Institutional Archive of the Naval Postgraduate School Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Theses and Dissertations Thesis Collection 2008-12 Military authoritarian regimes and economic development the ROK's economic take-off under Park Chung Hee Park, Kisung. Monterey, California. Naval Postgraduate School http://hdl.handle.net/10945/3773 NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL MONTEREY, CALIFORNIA THESIS MILITARY AUTHORITARIAN REGIMES AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT: THE ROK’S ECONOMIC TAKE-OFF UNDER PARK CHUNG HEE by Kisung Park December 2008 Thesis Advisor: Robert Looney Second Reader: Alice Miller Approved for public release, distribution is unlimited THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instruction, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188) Washington DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED December 2008 Master’s Thesis 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE Military Authoritarian Regimes and Economic 5. FUNDING NUMBERS Development: The ROK’s Economic Take-off under Park Chung Hee 6. -

Surviving Through the Post-Cold War Era: the Evolution of Foreign Policy in North Korea

UC Berkeley Berkeley Undergraduate Journal Title Surviving Through The Post-Cold War Era: The Evolution of Foreign Policy In North Korea Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4nj1x91n Journal Berkeley Undergraduate Journal, 21(2) ISSN 1099-5331 Author Yee, Samuel Publication Date 2008 DOI 10.5070/B3212007665 Peer reviewed|Undergraduate eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Introduction “When the establishment of ‘diplomatic relations’ with south Korea by the Soviet Union is viewed from another angle, no matter what their subjective intentions may be, it, in the final analysis, cannot be construed otherwise than openly joining the United States in its basic strategy aimed at freezing the division of Korea into ‘two Koreas,’ isolating us internationally and guiding us to ‘opening’ and thus overthrowing the socialist system in our country [….] However, our people will march forward, full of confidence in victory, without vacillation in any wind, under the unfurled banner of the Juche1 idea and defend their socialist position as an impregnable fortress.” 2 The Rodong Sinmun article quoted above was published in October 5, 1990, and was written as a response to the establishment of diplomatic relations between the Soviet Union, a critical ally for the North Korean regime, and South Korea, its archrival. The North Korean government’s main reactions to the changes taking place in the international environment during this time are illustrated clearly in this passage: fear of increased isolation, apprehension of external threats, and resistance to reform. The transformation of the international situation between the years of 1989 and 1992 presented a daunting challenge for the already struggling North Korean government. -

Korean War Module Day 01

KOREAN WAR MODULE DAY 01 MODULE OVERVIEW HISTORICAL THINKING SKILLS: CONTENT: Developments and Processes People and states around the world 1.B Explain a historical concept, development, or challenged the existing political and social process. order in varying ways, leading to Claims and Evidence in Sources unprecedented worldwide conflicts. 3.B Identify the evidence used in a source to support an argument. 3.C Compare the arguments or main ideas of two sources. 3.D Explain how claims or evidence support, modify, or refute a source’s argument Argumentation 6.D Corroborate, qualify, or modify an argument using diverse and alternative evidence in order to develop a complex argument. This argument might: o Explain the nuance of an issue by analyzing multiple variables. o Explain relevant and insightful connections within and across periods. D WAS THE KOREAN WAR A PRODUCT OF DECOLONIZATION OR THE COLD WAR? A Y CLASS ACTIVITY: Structured Academic Controversy 1 Students will engage in a Structured Academic Controversy (SAC) to develop historical thinking skills in argumentation by making historically defensible claims supported by specific and relevant evidence. AP ALIGNED ASSESSMENT: Thesis Statement Students will analyze primary and secondary sources to construct arguments with multiple claims and will focus on creating a complex thesis statement that evaluates the extent to which the Korean War was a product of decolonization and the Cold War. D EVALUATE THE EXTENT TO WHICH HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENTS IN THE POST- A WAR PERIOD WERE CAUSED BY DECOLONIZATION OR THE COLD WAR? Y CLASS ACTIVITY: Gallery Walk 2 Students will analyze multiple primary and secondary sources in a gallery walk activity. -

![September 30, 1949 Letter, Syngman Rhee to Dr. Robert T. Oliver [Soviet Translation]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6467/september-30-1949-letter-syngman-rhee-to-dr-robert-t-oliver-soviet-translation-696467.webp)

September 30, 1949 Letter, Syngman Rhee to Dr. Robert T. Oliver [Soviet Translation]

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified September 30, 1949 Letter, Syngman Rhee to Dr. Robert T. Oliver [Soviet Translation] Citation: “Letter, Syngman Rhee to Dr. Robert T. Oliver [Soviet Translation],” September 30, 1949, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, CWIHP Archive. Translated by Gary Goldberg. https://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/119385 Summary: Letter from Syngman Rhee translated into Russian. The original was likely found when the Communists seized Seoul. Syngman Rhee urges Oliver to come to South Korea to help develop the nation independent of foreign invaders and restore order to his country. Credits: This document was made possible with support from the Leon Levy Foundation. Original Language: Russian Contents: English Translation Scan of Original Document continuation of CABLE Nº 600081/sh “30 September 1949 to: DR. ROBERT T. OLIVER from: PRESIDENT SYNGMAN RHEE I have received your letters and thank you for them. I do not intend to qualify Mr. KROCK [sic] as a lobbyist or anything of that sort. Please, in strict confidence get in contact with Mr. K. [SIC] and with Mr. MEADE [sic] and find out everything that is necessary. If you think it would be inadvisable to use Mr. K with respect to what Mr. K told you, we can leave this matter without consequences. In my last letter I asked you to inquire more about K. in the National Press Club. We simply cannot use someone who does not have a good business reputation. Please be very careful in this matter. There is some criticism about the work which we are doing. -

Killing Hope U.S

Killing Hope U.S. Military and CIA Interventions Since World War II – Part I William Blum Zed Books London Killing Hope was first published outside of North America by Zed Books Ltd, 7 Cynthia Street, London NI 9JF, UK in 2003. Second impression, 2004 Printed by Gopsons Papers Limited, Noida, India w w w.zedbooks .demon .co .uk Published in South Africa by Spearhead, a division of New Africa Books, PO Box 23408, Claremont 7735 This is a wholly revised, extended and updated edition of a book originally published under the title The CIA: A Forgotten History (Zed Books, 1986) Copyright © William Blum 2003 The right of William Blum to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Cover design by Andrew Corbett ISBN 1 84277 368 2 hb ISBN 1 84277 369 0 pb Spearhead ISBN 0 86486 560 0 pb 2 Contents PART I Introduction 6 1. China 1945 to 1960s: Was Mao Tse-tung just paranoid? 20 2. Italy 1947-1948: Free elections, Hollywood style 27 3. Greece 1947 to early 1950s: From cradle of democracy to client state 33 4. The Philippines 1940s and 1950s: America's oldest colony 38 5. Korea 1945-1953: Was it all that it appeared to be? 44 6. Albania 1949-1953: The proper English spy 54 7. Eastern Europe 1948-1956: Operation Splinter Factor 56 8. Germany 1950s: Everything from juvenile delinquency to terrorism 60 9. Iran 1953: Making it safe for the King of Kings 63 10. -

Truth and Reconciliation� � Activities of the Past Three Years�� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �

Truth and Reconciliation Activities of the Past Three Years CONTENTS President's Greeting I. Historical Background of Korea's Past Settlement II. Introduction to the Commission 1. Outline: Objective of the Commission 2. Organization and Budget 3. Introduction to Commissioners and Staff 4. Composition and Operation III. Procedure for Investigation 1. Procedure of Petition and Method of Application 2. Investigation and Determination of Truth-Finding 3. Present Status of Investigation 4. Measures for Recommendation and Reconciliation IV. Extra-Investigation Activities 1. Exhumation Work 2. Complementary Activities of Investigation V. Analysis of Verified Cases 1. National Independence and the History of Overseas Koreans 2. Massacres by Groups which Opposed the Legitimacy of the Republic of Korea 3. Massacres 4. Human Rights Abuses VI. MaJor Achievements and Further Agendas 1. Major Achievements 2. Further Agendas Appendices 1. Outline and Full Text of the Framework Act Clearing up Past Incidents 2. Frequently Asked Questions about the Commission 3. Primary Media Coverage on the Commission's Activities 4. Web Sites of Other Truth Commissions: Home and Abroad President's Greeting In entering the third year of operation, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Republic of Korea (the Commission) is proud to present the "Activities of the Past Three Years" and is thankful for all of the continued support. The Commission, launched in December 2005, has strived to reveal the truth behind massacres during the Korean War, human rights abuses during the authoritarian rule, the anti-Japanese independence movement, and the history of overseas Koreans. It is not an easy task to seek the truth in past cases where the facts have been hidden and distorted for decades. -

Ecfg Southkorea 2020Ed.Pdf

About this Guide Re This guide is designed to prepare you to deploy to culturally complex environments and achieve mission objectives. The publi fundamental information contained within will help you understand the cultural dimension of your assigned location and gain skills necessary for success. (Photo: Girl holds prayer candle during Lotus c Lantern Festival in Seoul). o The guide consists of 2 parts: f Part 1 is the “Culture Sou General” section, which provides the foundational knowledge you need to operate effectively in any global t environment with a focus on East Asia. h Part 2 is the “Culture Specific” section, which describes K unique cultural features of South Korean society. It applies culture-general concepts to help increase your knowledge of o your assigned deployment rea location. This section is meant to complement other pre-deployment training. (Photo: Korean dancers C honor US forces during a ul cultural event). t For more information, visit the u Air Force Culture and re Language Center (AFCLC) website at www.airuniversity.af.edu/AFCLC/ or contact the AFCLC Region Team at [email protected]. Guid Disclaimer: All text is the property of the AFCLC and may not be modified by a change in title, content, or labeling. It may be reproduced in its current format with the express permission of the AFCLC. All photography is provided as a courtesy of the e US government, Wikimedia, and other sources as indicated. GENERAL CULTURE PART 1 – CULTURE GENERAL What is Culture? Fundamental to all aspects of human existence, culture shapes the way humans view life and functions as a tool we use to adapt to our social and physical environments. -

The Causes of the Korean War, 1950-1953

The Causes of the Korean War, 1950-1953 Ohn Chang-Il Korea Military Academy ABSTRACT The causes of the Korean War (1950-1953) can be examined in two categories, ideological and political. Ideologically, the communist side, including the Soviet Union, China, and North Korea, desired to secure the Korean peninsula and incorporate it in a communist bloc. Politically, the Soviet Union considered the Korean peninsula in the light of Poland in Eastern Europe—as a springboard to attack Russia—and asserted that the Korean government should be “loyal” to the Soviet Union. Because of this policy and strategic posture, the Soviet military government in North Korea (1945-48) rejected any idea of establishing one Korean government under the guidance of the United Nations. The two Korean governments, instead of one, were thus established, one in South Korea under the blessing of the United Nations and the other in the north under the direction of the Soviet Union. Observing this Soviet posture on the Korean peninsula, North Korean leader Kim Il-sung asked for Soviet support to arm North Korean forces and Stalin fully supported Kim and secured newly-born Communist China’s support for the cause. Judging that it needed a buffer zone against the West and Soviet aid for nation building, the Chinese government readily accepted a role to aid North Korea, specifically, in case of full American intervention in the projected war. With full support from the Soviet Union and comradely assistance from China, Kim Il-sung attacked South Korea with forces that were better armed, equipped, and prepared than their counterparts in South Korea. -

Comparative Study of Command and Control Structure Between Rok and Us Field Artillery Battalion

Proceedings of the 2015 Winter Simulation Conference L. Yilmaz, W. K. V. Chan, I. Moon, T. M. K. Roeder, C. Macal, and M. D. Rossetti, eds. COMPARATIVE STUDY OF COMMAND AND CONTROL STRUCTURE BETWEEN ROK AND US FIELD ARTILLERY BATTALION Ahram Kang Doyun Kim Junseok Lee Jang Won Bae Il-Chul Moon Department of Industrial and Systems Engineering KAIST, 335 Gwahangno Yusung-gu Daejon, 305-701, REPUBLIC OF KOREA ABSTRACT One of the main points of the Republic of Korea (ROK) military reformations is to reduce the number of personnel with the strengthened arsenal. However, the number of North Korean artillery forces far surpasses the ROK artillery forces, and the threat of mass destruction by these artillery remains in the Korean Peninsula. The aim of this study was to find the alternative field artillery operations and organization. This study presents a counterfire operation multi-agent model using LDEF formalism and its virtual experiments. The virtual experiments compared 1) the damage effectiveness between battalion and battery missions and 2) the effectiveness of command and control structures in the ROK and US artillery. Their results showed that splitting the units with strengthened guns and integrated C2 structure shows better performance in terms of damage effectiveness. We believe that this paper is basic research for the future ROK-US combined division, C2 network, and operations. 1 INTRODUCTION The threats from North Korea are various in these days. North Korea currently focuses on asymmetric warfare capabilities. For example, it launched three times to test the intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) in 2013. They also developed new types of multiple launcher rockets and tested them by shooting projectiles into the near sea.