Using Contract Law to Tackle the Coaching Carousel Stephen F

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Football Coaching Records

FOOTBALL COACHING RECORDS Overall Coaching Records 2 Football Bowl Subdivision (FBS) Coaching Records 5 Football Championship Subdivision (FCS) Coaching Records 15 Division II Coaching Records 26 Division III Coaching Records 37 Coaching Honors 50 OVERALL COACHING RECORDS *Active coach. ^Records adjusted by NCAA Committee on Coach (Alma Mater) Infractions. (Colleges Coached, Tenure) Yrs. W L T Pct. Note: Ties computed as half won and half lost. Includes bowl 25. Henry A. Kean (Fisk 1920) 23 165 33 9 .819 (Kentucky St. 1931-42, Tennessee St. and playoff games. 44-54) 26. *Joe Fincham (Ohio 1988) 21 191 43 0 .816 - (Wittenberg 1996-2016) WINNINGEST COACHES ALL TIME 27. Jock Sutherland (Pittsburgh 1918) 20 144 28 14 .812 (Lafayette 1919-23, Pittsburgh 24-38) By Percentage 28. *Mike Sirianni (Mount Union 1994) 14 128 30 0 .810 This list includes all coaches with at least 10 seasons at four- (Wash. & Jeff. 2003-16) year NCAA colleges regardless of division. 29. Ron Schipper (Hope 1952) 36 287 67 3 .808 (Central [IA] 1961-96) Coach (Alma Mater) 30. Bob Devaney (Alma 1939) 16 136 30 7 .806 (Colleges Coached, Tenure) Yrs. W L T Pct. (Wyoming 1957-61, Nebraska 62-72) 1. Larry Kehres (Mount Union 1971) 27 332 24 3 .929 31. Chuck Broyles (Pittsburg St. 1970) 20 198 47 2 .806 (Mount Union 1986-2012) (Pittsburg St. 1990-2009) 2. Knute Rockne (Notre Dame 1914) 13 105 12 5 .881 32. Biggie Munn (Minnesota 1932) 10 71 16 3 .806 (Notre Dame 1918-30) (Albright 1935-36, Syracuse 46, Michigan 3. -

Human Dignity Issues in the Sports Business Industry

DEVELOPING RESPONSIBLE CONTRIBUTORS | Human Dignity Issues in the Sports Business Industry Matt Garrett is the chair of the Division of Physical Education and Sport Studies and coordinator of the Sport Management Program at Loras College. His success in the sport industry includes three national championships in sport management case study tournaments, NCAA Division III tournament appearances as a women’s basketball and softball coach, and multiple youth baseball championships. Developing Responsible Contributors draws on these experiences, as well as plenty of failures, to explore a host of issues tied to human dignity in the sport business industry. These include encounters with hazing and other forms of violence in sport, inappropriate pressures on young athletes, and the exploitation of college athletes and women in the sport business industry. Garrett is the author of Preparing the Successful Coach and Matt Garrett Timeless: Recollections of Family and America’s Pastime. He lives in Dubuque with his wife and three children. | Human Dignity Issues in the LORAS COLLEGE PRESS Sports Business Industry Matt Garrett PRESS i Developing Responsible Contributors: Human Dignity Issues in the Sport Business Industry Matthew Garrett, Ph.D. Professor of Physical Education and Sports Studies Loras College Loras College Press Dubuque, Iowa ii Volume 5 in the Frank and Ida Goedken Series Published with Funds provided by The Archbishop Kucera Center for Catholic Intellectual and Spiritual Life at Loras College. Published by the Loras College Press (Dubuque, Iowa), David Carroll Cochran, Director. Publication preparation by Helen Kennedy, Marketing Department, Loras College. Cover Design by Mary Kay Mueller, Marketing Department, Loras College. -

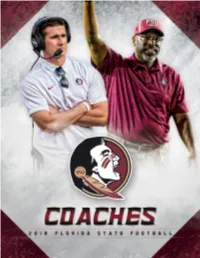

04 Coaches-WEB.Pdf

59 Experience: 1st season at FSU/ Taggart jumped out to a hot start at Oregon, leading the Ducks to a 77-21 win in his first 9th as head coach/ game in Eugene. The point total tied for the highest in the NCAA in 2017, was Oregon’s 20th as collegiate coach highest since 1916 and included a school-record nine rushing touchdowns. The Hometown: Palmetto, Florida offensive fireworks continued as Oregon scored 42 first-half points in each of the first three games of the season, marking the first time in school history the program scored Alma Mater: Western Kentucky, 1998 at least 42 points in one half in three straight games. The Ducks began the season Family: wife Taneshia; 5-1 and completed the regular season with another offensive explosion, defeating rival sons Willie Jr. and Jackson; Oregon State 69-10 for the team’s seventh 40-point offensive output of the season. daughter Morgan Oregon ranked in the top 30 in the NCAA in 15 different statistical categories, including boasting the 12th-best rushing offense in the country rushing for 251.0 yards per game and the 18th-highest scoring offense averaging 36.0 points per game. On defense, the Florida State hired Florida native Willie Taggart to be its 10th full-time head football Ducks ranked 24th in the country in third-down defense allowing a .333 conversion coach on Dec. 5, 2017. Taggart is considered one of the best offensive minds in the percentage and 27th in fourth-down defense at .417. The defense had one of the best country and has already proven to be a relentless and effective recruiter. -

African American Head Football Coaches at Division 1 FBS Schools: a Qualitative Study on Turning Points

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2015 African American Head Football Coaches at Division 1 FBS Schools: A Qualitative Study on Turning Points Thaddeus Rivers University of Central Florida Part of the Educational Leadership Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Doctoral Dissertation (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Rivers, Thaddeus, "African American Head Football Coaches at Division 1 FBS Schools: A Qualitative Study on Turning Points" (2015). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 1469. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/1469 AFRICAN AMERICAN HEAD FOOTBALL COACHES AT DIVISION I FBS SCHOOLS: A QUALITATIVE STUDY ON TURNING POINTS by THADDEUS A. RIVERS B.S. University of Florida, 2001 M.A. University of Central Florida, 2008 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education in the Department of Child, Family and Community Sciences in the College of Education and Human Performance at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Fall Term 2015 Major Professor: Rosa Cintrón © 2015 Thaddeus A. Rivers ii ABSTRACT This dissertation was centered on how the theory ‘turning points’ explained African American coaches ascension to Head Football Coach at a NCAA Division I FBS school. This work (1) identified traits and characteristics coaches felt they needed in order to become a head coach and (2) described the significant events and people (turning points) in their lives that have influenced their career. -

Bobby Petrino Is Changing the Game for WKU

DAILY NEWS FOOTBALL SEASON PREVIEW 2013 WINNINGEDGE Bobby Petrino is changing the game for WKU Cover photo by Alex Slitz and Miranda Pederson FB2 PAGE 2A - FRIDAY, AUGUST 23, 2013 Football 2013 DAILY NEWS, BOWLING GREEN, KENTUCKY Bowling Green still reaching new heights Purples hoping pieces come together for run at third consecutive state championship By ZACH GREENWELL The Daily News CLASS 5A, DISTRICT 2 [email protected]/783-3239 There’s no shying away from expecta- tions this season for the Bowling Green Purples. They enter 2013 with two straight 2013 SCHEDULE Class 5A state championships and 30 consecutive wins, along with a solid argu- ment for the label as the top team in all of Kentucky. MaxPreps ranked them as such earlier this month. But just because the Purples haven’t lost since Nov. 12, 2010, doesn’t mean there’s not more work to do. “Right now, coaches are telling us to be leaders,” senior receiver Nacarius Fant said. “They’re not making us think about that three-peat. They’re talking about getting better every day, and that’s what we’re focused on. We know teams are since hired Ben Bruni, Curtis Cotton, hunting for us.” Junior Hayes and Mike Federspiel. Bowling Green returns 16 starters from “We’re going to have to move,” Wallace last year’s team, which bested Cooper in said of the defense. “We’re going to have the state final. It graduated a small senior class with to be able to run well because we’re not few standouts, but it’s a group that provid- very big up front defensively. -

2014 CLEMSON TIGERS Football Clemson (22 AP, 24 USA) Vs

2014 CLEMSON TIGERS Football Clemson (22 AP, 24 USA) vs. Florida State (1 AP, 1 USA) Clemson Tigers Florida State Seminoles Record, 2014 .............................................1-1, 0-0 ACC Record, 2014 .........................................2-0, 0-0 in ACC Saturday, September 20, 2014 Location ......................................................Clemson, SC Location ..................................................Talahassee, Fla Kickoff: 8:18 PM Colors .............................. Clemson Orange and Regalia Colors .......................................................Garnet & Gold Doak Campbell Stadium Enrollment ............................................................20,768 Enrollment ............................................................41,477 Athletic Director ........Dan Radakovich (Indiana, PA, ‘80) Tallahassee, FL Athletic Director ............... Stan Wilcox (Notre Dame ‘81) Head Coach .....................Dabo Swinney, Alabama ‘93 Head Coach ..................... Jimbo Fisher(Samford ‘87) Clemson Record/6th full year) ..................... 52-24 (.684) School Record ..................................47-10 (5th season) Television : ABC Home Record ............................................. 33-6 (.846) Overall ............................................47-10 (5th season) (Chris Fowler, Kirk Herbstreit, Heather Cox) Away Record ............................................ 14-14 (.500) Offensive Coordinator: .......................Lawrence Dawsey, Neutral Record ........................................................5-4 -

2018 CONFERENCE USA (In Alpha Order) CUSA Is at Tier Two, Meaning There Are No Individual Team Sheets and No Game by Game Rush Data Or Rush Stat Plays Tabulated

2018 CONFERENCE USA (in alpha order) CUSA is at tier two, meaning there are no individual team sheets and no game by game rush data or rush stat plays tabulated. CSUA EAST Charlotte Each year I “publish” my bottom five coach report. Brad Lambert made the list last year and proceeded to “lead” his team to one win! Blame the staff? Lambert cleaned house, firing both coordinators and firing and demoting other assistants. 18 starters return. Lose again and it will be clear where the next change will occur. AREAS TO WATCH: Charlotte loses just two WR’s, a center and one LB from the ’17 starting lineup. This will be a heavily veteran team. Their QB hit 47.7% last year. In 7-12 games the point O was 14 or less. I like the lead RB. The new offensive coordinator was productive at Youngstown St. Charlotte intercepted just two passes in ’17! With ten returning starters this will change. They have 25 defensive sacks in their last 24 games. The run D was below average and the pass D was over 69%. They’ll improve, but to what extent. Glenn Spencer was decent as the defensive coordinator at Oklahoma St. This seems like a splash hire. All three kickers return but they combined to go 4-13 last year. ‘18 PREVIEW: Last year in this spot I said to post check their stats vs. Eastern Michigan. The stats were not pretty. Let’s hope they improve with this depth opening up vs. 4-7 Fordham. Games 2-4 are hosting App. -

87 Andrew Pettijohn

WESTERN KENTUCKY UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF ATHLETICS 1605 Avenue of Champions Bowling Green, Ky. 42101 270-745-4298 www.WKUSports.com CREDITS EXECUTIVE EDITOR Chris Glowacki EDITORIAL ASSISTANCE Kyle Allen, Melissa Anderson and Michael Schroeder LAYOUT Chris Glowacki Printed by Gerald Printing, Bowling Green, Ky. (Printed with state funds) © 2011, Western Kentucky University Department of Athletics WESTERN KENTUCKY UNIVERSITY STATEMENT OF PURPOSE As a nationally prominent university, Western Kentucky University engages the globe in acclaimed, technologically enhanced academic programs. An inspiring faculty promotes entrepreneurial success and a unique campus spirit to attract an intellectually exciting and diverse family of the nation’s best students. WKU provides students with rigorous academic programs in education, the liberal arts and sciences, business, and traditional and emerging professional programs, with empha- sis at the baccalaureate level, complemented by relevant associate and graduate-level programs. The University places a premium on teaching and student learning. WKU faculty engage in creative activity and diverse scholarship, including basic and applied research, designed to expand knowledge, improve instruction, increase learning, and provide optimum service to the state and nation. The University directly supports its constituents in its designated service areas of Kentucky with professional and technical expertise, cultural enrichment, and educational assistance. The University encourages applied research and public ser- vice in support of economic development, quality of life, and improvement of education at all levels, especially elementary and secondary schools. In particular, WKU faculty contrib- ute to the identifi cation and solution of key social, economic, scientifi c, health, and environ- mental problems within its reach, but particularly throughout its primary service area. -

11.02.17 Emerald Gameday MASTER.Indd

GAMEDAY FRESH WOUNDS AFTER ALLOWING THE MOST POINTS at Autzen since before World War II, Oregon looks to beat its rival Washington in a Saturday night showdown in Seattle. PLAYERS TO WATCH VS WASHINGTON DUCKS FIGHTING FOR A BOWL GAME OFFENSIVE LINE PUNISHING OPPONENTS The Fifth Street Public Market is the area’s premier GAMEDAY shopping destination. Here you’ll find a colorful GAMEDAY, the Emerald’s football edition, is published by Emerald Media Group, Inc., the collection of unique and enchanting stores, independent nonprofi t news company at the restaurants, and cafés, as well as a University of Oregon founded in 1900. EMERALD MEDIA GROUP boutique hotel. 1395 University St., #302, Eugene, OR 97403 The Fifth Street Public Market is the area’s premier 541.346.5511 | dailyemerald.com NEWSROOM shopping destination. Here you’ll find a colorful Editor in Chief collection of unique and enchanting stores, Jack Pitcher Art Director restaurants, and cafés, as well as a Emily Harris TheThe Fifth Fifth Street Street Public Public Market Market isis thethe area’s premier premier Print Managing Editor shoppingTheboutiqueshopping Fifth destination. hotel.Streetdestination. Public Here Here Market you’ll you’ll is thefindfind area’s aa colorfulcolorful premier Mateo Sundberg collectioncollection of uniqueof unique and and enchanting enchanting stores, Sports Editors restaurants,shoppingrestaurants, destination.and and cafés, cafés, Hereas as well well you’ll asas find a a colorful Jack Butler boutiqueboutique hotel. hotel. Gus Morris collection of unique and enchanting stores, Shawn Medow restaurants, and cafés, as well as a Writers Kylee O’Connor boutique hotel. Shawn Medow Zak Laster Cole Kundich Gus Morris Jack Butler Designers Regan Nelson Theo Mechain Kelly Kondo Maranda Yob Don’t Get IMPACTED, BUSINESS President & Publisher Make the WISE Choice. -

Mega Conferences

Non-revenue sports Football, of course, provides the impetus for any conference realignment. In men's basketball, coaches will lose the built-in recruiting tool of playing near home during conference play and then at Madison Square Garden for the Big East Tournament. But what about the rest of the sports? Here's a look at the potential Missouri Pittsburgh Syracuse Nebraska Ohio State Northwestern Minnesota Michigan St. Wisconsin Purdue State Penn Michigan Iowa Indiana Illinois future of the non-revenue sports at Rutgers if it joins the Big Ten: BASEBALL Now: Under longtime head coach Fred Hill Sr., the Scarlet Knights made the Rutgers NCAA Tournament four times last decade. The Big East Conference’s national clout was hurt by the defection of Miami in 2004. The last conference team to make the College World Series was Louisville in 2007. After: Rutgers could emerge as the class of the conference. You find the best baseball either down South or out West. The power conferences are the ACC, Pac-10 and SEC. A Big Ten team has not made the CWS since Michigan in 1984. MEN’S CROSS COUNTRY Now: At the Big East championships in October, Rutgers finished 12th out of 14 teams. Syracuse won the Big East title and finished 14th at nationals. Four other Big East schools made the Top 25. After: The conferences are similar. Wisconsin won the conference title and took seventh at nationals. Two other schools made the Top 25. MEN’S GOLF Now: The Scarlet Knights have made the NCAA Tournament twice since 1983. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD—HOUSE, Vol. 153, Pt. 2 January 29, 2007 for Spearheading the Postal Reorganization Murphy; David Walker; Andy Iro; Jon Curry; Mr

2510 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD—HOUSE, Vol. 153, Pt. 2 January 29, 2007 for spearheading the Postal Reorganization Murphy; David Walker; Andy Iro; Jon Curry; Mr. BOUSTANY. Mr. Speaker, I yield Act of 1970. After his Senate career was over, Greg Curry; Bryan Byrne; Paul Kierstead; myself such times as I may consume. McGee later served as U.S. Ambassador to Tino Nunez; Tyler Rosenlund; Alfonso Mr. Speaker, I rise today in support Motagalvan; Eric Frimpong; Chris Pontius; of House Resolution 70. This resolution the Organization of American States from Nick Perera; Eric Avila; Evan Patterson; 1977 to 1981. Brennan Tennelle; Kyle Kaveny; Andrew recognizes the outstanding 2006 record As a professor and Senator, Gale McGee Proctor; Bongomin Otii; Bryant Rueckner; of the University of California at Santa dedicated 30 years of his life serving the peo- Tony Chinakwe; Jason Badger; Jordan Barbara men’s soccer team as well as ple of Wyoming. In August of 2006, the Lar- Kaplan; Drew Gleason; C.J. Cintas; and Guil- their triumph in winning the univer- amie City Council recognized that service by lermo Jalomo: Now, therefore, be it sity’s first-ever national title in soccer passing a resolution supporting the naming of Resolved, That the House of Representa- and only the second in any other sport. tives congratulates the University of Cali- With a 2–1 victory over the Univer- their local post office after Senator McGee. fornia at Santa Barbara men’s soccer team, Due to that local support, I was proud to intro- the Gauchos, and Coaches Tim Vom Steeg, sity of California at Los Angeles at the duce H.R. -

Big 12 Mens Basktball Preview

Big 12 Mens Basktball Preview Nov. 27 - Dec. 3, 2020 Vol. 19, Issue 14 www.sportspagdfw.com FREE 2 November 27, 2020 - December 3, 2020 | The Sports Page Weekly | Volume 19 Issue 14 | www.sportspagedfw.com | follow us on twitter @sportspagdfw.com Follow us on twitter @sportspagedfw | www.sportspagedfw.com | The Sports Page Weekly | Volume 19 - Issue 14 | November 27, 2020 - December 3, 2020 3 Nov. 27, 2020 - Dec. 3, 2020 AROUND THE AREA Vol. 19, Issue 14 LOCAL NEWS OF INTEREST sportspagedfw.com Established 2002 Gift of lights return to TMS Cover Photo: 4 AROUND THE AREA who wear a crazy Christmas sweater Tickets to 'Gift of Lights' are available 5 SMU REPORT online (giftoflightstexas.com) for $30 BY DIC HUMPHREY (cars/trucks), $50 (RVs/truck trailers), and 6 TOM’S TIP OF THE WEEK $60 (bus of 20 people). Passengers must BY TOM WARD remain in their vehicles due to COVID-19. TIGER AND SON TO PLAY IN Motorcycles and passengers in truck beds PNC CHAMPIONSHIP and trailers are prohibited. 7 BY PGATOUR.COM BIG 12 MENS BASKETBALL 8 PREVIEW BY RYAN GILBERT College Football Playoff Selection Gift of lightds return to TMS with The in-vehicle event has always been Committee Rankings Games Played SEC WEEK 10 PREDICTIONS already COVID-19 friendly drive- socially distanced so guests’ safety will be 10 BY ROBERT CORTINEZ through Saturday, November 21 through experience seamless. Rank Team Overall • Millions of lights cover two-mile drive “This has definitely been a year where BIG 12 WEEK 13 PREDICTIONS Record 11 BY JOHN MOSS for No Limits, Texas annual