SC10-364 Merits Answer Brief

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CONTENTS August 2021

CONTENTS August 2021 I. EXECUTIVE ORDERS JBE 21-12 Bond Allocation 2021 Ceiling ..................................................................................................................... 1078 II. EMERGENCY RULES Children and Family Services Economic Stability Section—TANF NRST Benefits and Post-FITAP Transitional Assistance (LAC 67:III.1229, 5329, 5551, and 5729) ................................................................................................... 1079 Licensing Section—Sanctions and Child Placing Supervisory Visits—Residential Homes (Type IV), and Child Placing Agencies (LAC 67:V.7109, 7111, 7311, 7313, and 7321) ..................................................... 1081 Governor Division of Administration, Office of Broadband Development and Connectivity—Granting Unserved Municipalities Broadband Opportunities (GUMBO) (LAC 4:XXI.Chapters 1-7) .......................................... 1082 Health Bureau of Health Services Financing—Programs and Services Amendments due to the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Public Health Emergency—Home and Community-Based Services Waivers and Long-Term Personal Care Services....................................................................................... 1095 Office of Aging and Adult Services—Programs and Services Amendments due to the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Public Health Emergency—Home and Community-Based Services Waivers and Long-Term Personal Care Services....................................................................................... 1095 Office -

DACIN SARA Repartitie Aferenta Trimestrului III 2019 Straini TITLU

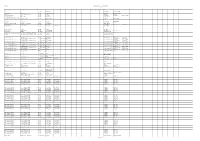

DACIN SARA Repartitie aferenta trimestrului III 2019 Straini TITLU TITLU ORIGINAL AN TARA R1 R2 R3 R4 R5 R6 R7 R8 R9 R10 R11 S1 S2 S3 S4 S5 S6 S7 S8 S9 S10 S11 S12 S13 S14 S15 Greg Pruss - Gregory 13 13 2010 US Gela Babluani Gela Babluani Pruss 1000 post Terra After Earth 2013 US M. Night Shyamalan Gary Whitta M. Night Shyamalan 30 de nopti 30 Days of Night: Dark Days 2010 US Ben Ketai Ben Ketai Steve Niles 300-Eroii de la Termopile 300 2006 US Zack Snyder Kurt Johnstad Zack Snyder Michael B. Gordon 6 moduri de a muri 6 Ways to Die 2015 US Nadeem Soumah Nadeem Soumah 7 prichindei cuceresc Broadway-ul / Sapte The Seven Little Foys 1955 US Melville Shavelson Jack Rose Melville Shavelson prichindei cuceresc Broadway-ul A 25-a ora 25th Hour 2002 US Spike Lee David Benioff Elaine Goldsmith- A doua sansa Second Act 2018 US Peter Segal Justin Zackham Thomas A fost o data in Mexic-Desperado 2 Once Upon a Time in Mexico 2003 US Robert Rodriguez Robert Rodriguez A fost odata Curly Once Upon a Time 1944 US Alexander Hall Lewis Meltzer Oscar Saul Irving Fineman A naibii dragoste Crazy, Stupid, Love. 2011 US Glenn Ficarra John Requa Dan Fogelman Abandon - Puzzle psihologic Abandon 2002 US Stephen Gaghan Stephen Gaghan Acasa la coana mare 2 Big Momma's House 2 2006 US John Whitesell Don Rhymer Actiune de recuperare Extraction 2013 US Tony Giglio Tony Giglio Acum sunt 13 Ocean's Thirteen 2007 US Steven Soderbergh Brian Koppelman David Levien Acvila Legiunii a IX-a The Eagle 2011 GB/US Kevin Macdonald Jeremy Brock - ALCS Les aventures extraordinaires d'Adele Blanc- Adele Blanc Sec - Aventurile extraordinare Luc Besson - Sec - The Extraordinary Adventures of Adele 2010 FR/US Luc Besson - SACD/ALCS ale Adelei SACD/ALCS Blanc - Sec Adevarul despre criza Inside Job 2010 US Charles Ferguson Charles Ferguson Chad Beck Adam Bolt Adevarul gol-golut The Ugly Truth 2009 US Robert Luketic Karen McCullah Kirsten Smith Nicole Eastman Lebt wohl, Genossen - Kollaps (1990-1991) - CZ/DE/FR/HU Andrei Nekrasov - Gyoergy Dalos - VG. -

Wakix, INN-Pitolisant

ANNEX I SUMMARY OF PRODUCT CHARACTERISTICS 1 This medicinal product is subject to additional monitoring. This will allow quick identification of new safety information. Healthcare professionals are asked to report any suspected adverse reactions. See section 4.8 for how to report adverse reactions. 1. NAME OF THE MEDICINAL PRODUCT Wakix 4.5 mg film-coated tablets Wakix 18 mg film-coated tablets 2. QUALITATIVE AND QUANTITATIVE COMPOSITION Wakix 4.5 mg film-coated tablet Each tablet contains pitolisant hydrochloride equivalent to 4.45 mg of pitolisant. Wakix 18 mg film-coated tablet Each tablet contains pitolisant hydrochloride equivalent to 17.8 mg of pitolisant. For the full list of excipients, see section 6.1. 3. PHARMACEUTICAL FORM Film-coated tablet (tablet) Wakix 4.5 mg film-coated tablet White, round, biconvex film-coated tablet, 3.7 mm diameter, marked with “5” on one side. Wakix 18 mg film-coated tablet White, round, biconvex film-coated tablet, 7.5 mm diameter marked with “20” on one side. 4. CLINICAL PARTICULARS 4.1 Therapeutic indications Wakix is indicated in adults for the treatment of narcolepsy with or without cataplexy (see also section 5.1). 4.2 Posology and method of administration Treatment should be initiated by a physician experienced in the treatment of sleep disorders. Posology Wakix should be used at the lowest effective dose, depending on individual patient response and tolerance, according to an up-titration scheme, without exceeding the dose of 36 mg/day: - Week 1: initial dose of 9 mg (two 4.5 mg tablets) per day. - Week 2: the dose may be increased to 18 mg (one 18 mg tablet) per day or decreased to 4.5 mg (one 4.5 mg tablet) per day. -

The TV Player Report a Beta Report Into Online TV Viewing

The TV Player Report A beta report into online TV viewing Week ending 18th December 2016 Table of contents Page 3 Introduction 4 Frequently asked questions 5 Aggregate on-demand and live viewing by TV player 6 Aggregate on-demand and live viewing by broadcaster group 7 Live streaming channels 9 Top 50 on-demand programmes – last week 10 Top 50 live programmes – last week 11 Top 50 on-demand programmes – last 4 weeks 12 Top 10 on-demand programmes by TV player – last week and 4 weeks 16 Top 10 live programmes by TV player – last week 19 Top 50 on-demand programmes by operating system – last week 22 Top 50 live programmes by operating system – last week 25 Top 50 on-demand programmes by operating system – last 4 weeks 28 Reference section Introduction In an era of constant change, BARB continues to develop its services in response to fragmenting behaviour patterns. Since our launch in 1981, there has been proliferation of platforms, channels and catch-up services. In recent years, more people have started to watch television and video content distributed through the internet. Project Dovetail is at the heart of our development strategy. Its premise is that BARB’s services need to harness the strengths of two complementary data sources. - BARB’s panel of 5,100 homes provides representative viewing information that delivers programme reach, demographic viewing profiles and measurement of viewers per screen. - Device-based data from web servers provides granular evidence of how online TV is being watched. The TV Player Report is the first stage of Project Dovetail. -

Federal Register/Vol. 81, No. 180/Friday, September 16, 2016

63860 Federal Register / Vol. 81, No. 180 / Friday, September 16, 2016 / Rules and Regulations DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND AAR/IP After Action Report/Improvement HSPD Homeland Security Presidential HUMAN SERVICES Plan Directive ACHC Accreditation Commission for HVA Hazard Vulnerability Analysis or Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Health Care, Inc. Assessment Services ACHE American College of Healthcare ICFs/IID Intermediate Care Facilities for Executives Individuals with Intellectual Disabilities AHA American Hospital Association ICR Information Collection Requirements 42 CFR Parts 403, 416, 418, 441, 460, AO Accrediting Organization IDG Interdisciplinary Group 482, 483, 484, 485, 486, 491, and 494 AOA/HFAP American Osteopathic IOM Institute of Medicine [CMS–3178–F] Association/Healthcare Facilities JPATS Joint Patient Assessment and Accreditation Program Tracking System RIN 0938–AO91 ASC Ambulatory Surgical Center LEP Limited English Proficiency ARCAH Accreditation Requirements for LD Leadership Medicare and Medicaid Programs; Critical Access Hospitals LPHA Local Public Health Agencies Emergency Preparedness ASPR Assistant Secretary for Preparedness LSC Life Safety Code Requirements for Medicare and and Response LTC Long Term Care Medicaid Participating Providers and BLS Bureau of Labor Statistics MMRS Metropolitan Medical Response Suppliers BTCDP Bioterrorism Training and System Curriculum Development Program MRC Medical Reserve Corps AGENCY: Centers for Medicare & CAH Critical Access Hospital MS Medical Staff Medicaid Services (CMS), HHS. -

Annotated Bibliography of Cause-Of-Death Validation Studies, 1958-80

� 1 , Annotated cm Bibliography of Cause-of-Death ,= Validation Studies: PROPERW OF THE 1958-1980 PUBLICATIONS5f3Afqc~ U)}TOW L!BMRV An annotated bibliography of studies relating to the errors in diagnosing, recording, coding, and tabulating cause of death. Data Evaluation and Methods Research Sertes 2, No 89 DHHS Publication No, (PHS) 82-1363 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Public Health Service Office of Health Research, Statistics, and Technology National Center for Health Statistics Hyattsvi[le, Md September, 1982 COPYRIGHT INFORMATION The National Center for Haalth Statistics has obtainad permission from the copyright holders to raproduce cartain quoted material in this report. Further reproduction of this material is prohibited without specific permission of the copyright holders. All othar material contained in the report is in the public domain and may be used and reprinted without special permission; citation as to source, howaver, is appreciated. SUGGESTED CITATION National Center for Health Statistics, A. Gittelsohn and P. Royston: Annotated bibliography of cause-of-death validation studies, 1958-80. Vita/ and Hea/th .Mdstics, Series 2, No. 89. DHHS Pub. No. (PHS) 82-1363. Public Health Setvica, Washington. U.S. Government Printing Office, Saptember, 1982. Library of Congrasa Cataloging in Publication Data Gittelsohn, Alan M. Annotated bibliography of cause-of death validation studies, 1958-1979. (Vital and health statistics, Serias 2, Data evaluation and methods rasaarch; no. 68) (DHHS publication; no (PHS) 81-1368) Authors: Alan Gittelsohn, Patricia N. Royston. 1. Death–Causes-Stat istics-Bibliography. 2. Death–Causas– Classification–bib biography. 3. Death–Proof and certification– Bibliography, 5. Errors, Theory of–bibliography. -

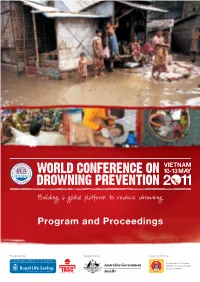

Program and Proceedings

Building a global platform to reduce drowning Program and Proceedings Presented by Supported by Country Partner Government of Vietnam Ministry of Labour, Invalids and Social Affairs 50 countries. 400 delegates. All committed to creating a world free from drowning preSented by country partnerS Government of Vietnam Ministry of Labour, Invalids and Social Affairs MAJOR SPONSOR Silver SponSor ScholarShip SupporterS Ausstraliatralia -- Mallaysiaaysia InInsstitutetitute Stream SponSor Maatschappij tot Redding van THE ROYAL LIFE SAVING SOCIETY Drenkelingen A Commonwealth Organisation vietnam ScholarShip partnerS Cooper Foundation 2 WorLd ConferenCe on droWnInG PreVentIon 2011 contents forward 4 abstraCts Background 10 Conference drowning Prevention Partners 12 027 Committees 16 Ambassadors 18 developing Countries Scholarship fund 20 INDex Child drowning epidemic & the danang declaration 22 349 Program aND abstraCts Program and Proceedings – Production Program Snapshot 24 editors Justin scarr (Convener) – Chief operating abstraCts officer, royal Life Saving Society – Australia; ILS drowning Prevention Keynote Addresses 27 Commission; development Coordinator, ILS Asia-Pacific Vietnam in focus 37 drowning in Low and Middle Income Countries 45 monique sharp (Conference Secretariat/ organiser) – national Manager, drowning research 91 Marketing and events, royal Life Saving Society - Australia Child drowning 121 matthew smeal (Media and emergency response and Medical Issues 139 Communications) – Communications Manager, International Programs, royal -

Timnath Town Council Meeting 6:00 PM - Tuesday, May 11, 2021 4750 Signal Tree Drive, Timnath, Colorado

AGENDA Timnath Town Council Meeting 6:00 PM - Tuesday, May 11, 2021 4750 Signal Tree Drive, Timnath, Colorado Page 1. CALL TO ORDER AND ROLL CALL 2. AMENDMENTS TO THE AGENDA 3. PUBLIC COMMENT The intent of this section is to allow the public to make comments on non- agenda items or items that do not have a public hearing available. Please keep comments to 3 minutes 4. CONSENT AGENDA 4.a. April 22, 2021 Check Register 3 - 18 April 22, 2021 Check Register 4.b. Approval of the April 27, 2021, Town Council Meeting Minutes 19 - 23 Timnath Town Council - 27 Apr 2021 - Minutes 4.c. ORDINANCE NO. 5, SERIES 2021, An Ordinance Approving the 24 - 39 Timnath Landing Planned Development Overlay Amendment - First Reading and Setting the Public Hearing for May 25, 2021 Staff Report - Pdf Ord 5 Narrative Planned Development Overlay Presented by: Kevin Koelbel 5. REPORTS 5.a. Mayor and Council Reports 6. BUSINESS 6.a. RESOLUTION NO. 26, SERIES 2021, A Resolution Authorizing and 40 - 55 Approving Timnath's Participation in the Metro Mortgage Assistance Plus Program, and Authorizing the Execution of the Delegation and Participation Agreement and Other Documents in Connection Therewith Staff Report - Pdf mDPA - Request to Participate - 01.15.21 metroDPA Program - CityCounty_04.15.2021 Reso 26 metroDPA - DelegationParticAgrmnt Timnath Presented by: Aaron Adams Page 1 of 107 6.b. RESOLUTION NO. 27, SERIES 2021, A Resolution Approving an 56 - 82 agreement with Colorado State University to conduct an Air Quality Monitoring Plan for the Town of Timnath Staff Report - Pdf Copy of Town Council Purchase Authorization_CSU Reso 27 CSU Agreement Presented by: Aaron Adams 6.c. -

National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2019’’

H. R. 5515 One Hundred Fifteenth Congress of the United States of America AT THE SECOND SESSION Begun and held at the City of Washington on Wednesday, the third day of January, two thousand and eighteen An Act To authorize appropriations for fiscal year 2019 for military activities of the Depart- ment of Defense, for military construction, and for defense activities of the Depart- ment of Energy, to prescribe military personnel strengths for such fiscal year, and for other purposes. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, SECTION 1. SHORT TITLE. (a) IN GENERAL.—This Act may be cited as the ‘‘John S. McCain National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2019’’. (b) REFERENCES.—Any reference in this or any other Act to the ‘‘National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2019’’ shall be deemed to be a reference to the ‘‘John S. McCain National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2019’’. SEC. 2. ORGANIZATION OF ACT INTO DIVISIONS; TABLE OF CONTENTS. (a) DIVISIONS.—This Act is organized into four divisions as follows: (1) Division A—Department of Defense Authorizations. (2) Division B—Military Construction Authorizations. (3) Division C—Department of Energy National Security Authorizations and Other Authorizations. (4) Division D—Funding Tables. (b) TABLE OF CONTENTS.—The table of contents for this Act is as follows: Sec. 1. Short title. Sec. 2. Organization of Act into divisions; table of contents. Sec. 3. Congressional defense committees. Sec. 4. Budgetary effects of this Act. DIVISION A—DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE AUTHORIZATIONS TITLE I—PROCUREMENT Subtitle A—Authorization Of Appropriations Sec. -

Vol. 84 Thursday, No. 26 February 7, 2019 Pages 2427–2704

Vol. 84 Thursday, No. 26 February 7, 2019 Pages 2427–2704 OFFICE OF THE FEDERAL REGISTER VerDate Sep 11 2014 20:48 Feb 06, 2019 Jkt 247001 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4710 Sfmt 4710 E:\FR\FM\07FEWS.LOC 07FEWS II Federal Register / Vol. 84, No. 26 / Thursday, February 7, 2019 The FEDERAL REGISTER (ISSN 0097–6326) is published daily, SUBSCRIPTIONS AND COPIES Monday through Friday, except official holidays, by the Office PUBLIC of the Federal Register, National Archives and Records Administration, under the Federal Register Act (44 U.S.C. Ch. 15) Subscriptions: and the regulations of the Administrative Committee of the Federal Paper or fiche 202–512–1800 Register (1 CFR Ch. I). The Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Assistance with public subscriptions 202–512–1806 Government Publishing Office, is the exclusive distributor of the official edition. Periodicals postage is paid at Washington, DC. General online information 202–512–1530; 1–888–293–6498 Single copies/back copies: The FEDERAL REGISTER provides a uniform system for making available to the public regulations and legal notices issued by Paper or fiche 202–512–1800 Federal agencies. These include Presidential proclamations and Assistance with public single copies 1–866–512–1800 Executive Orders, Federal agency documents having general (Toll-Free) applicability and legal effect, documents required to be published FEDERAL AGENCIES by act of Congress, and other Federal agency documents of public Subscriptions: interest. Assistance with Federal agency subscriptions: Documents are on file for public inspection in the Office of the Federal Register the day before they are published, unless the Email [email protected] issuing agency requests earlier filing. -

Assessment and Treatment of Patients with Suicidal Behaviors

PRACTICE GUIDELINE FOR THE Assessment and Treatment of Patients With Suicidal Behaviors WORK GROUP ON SUICIDAL BEHAVIORS Douglas G. Jacobs, M.D., Chair Ross J. Baldessarini, M.D. Yeates Conwell, M.D. Jan A. Fawcett, M.D. Leslie Horton, M.D., Ph.D. Herbert Meltzer, M.D. Cynthia R. Pfeffer, M.D. Robert I. Simon, M.D. Originally published in November 2003. This guideline is more than 5 years old and has not yet been updated to ensure that it reflects current knowledge and practice. In accordance with national standards, including those of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s National Guideline Clearinghouse (http://www.guideline.gov/), this guideline can no longer be assumed to be current. 1 Copyright 2010, American Psychiatric Association. APA makes this practice guideline freely available to promote its dissemination and use; however, copyright protections are enforced in full. No part of this guideline may be reproduced except as permitted under Sections 107 and 108 of U.S. Copyright Act. For permission for reuse, visit APPI Permissions & Licensing Center at http://www.appi.org/CustomerService/Pages/Permissions.aspx. AMERICAN PSYCHIATRIC ASSOCIATION STEERING COMMITTEE ON PRACTICE GUIDELINES John S. McIntyre, M.D., Chair Sara C. Charles, M.D., Vice-Chair Daniel J. Anzia, M.D. Ian A. Cook, M.D. Molly T. Finnerty, M.D. Bradley R. Johnson, M.D. James E. Nininger, M.D. Paul Summergrad, M.D. Sherwyn M. Woods, M.D., Ph.D. Joel Yager, M.D. AREA AND COMPONENT LIAISONS Robert Pyles, M.D. (Area I) C. Deborah Cross, M.D. (Area II) Roger Peele, M.D. -

U.S. Marshals Service (USMS)

United States Marshals Service FY 2021 Performance Budget President’s Budget Submission Salaries and Expenses Appropriation February 2020 This page left intentionally blank. Table of Contents I. United States Marshals Service (USMS) Overview .......................................................... 1 II. Summary of Program Changes ........................................................................................ 15 III. Appropriations Language and Analysis of Appropriations Language ........................ 16 IV. Program Activity Justification ......................................................................................... 17 A. Judicial and Courthouse Security ...............................................................................17 1. Program Description .................................................................................................17 2. Performance and Resource Tables ............................................................................19 3. Performance, Resources, and Strategies ...................................................................24 B. Fugitive Apprehension .................................................................................................26 1. Program Description .................................................................................................26 2. Performance and Resource Tables ............................................................................30 3. Performance, Resources, and Strategies ...................................................................38