Minor London Cinemas III.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Residential Update

Residential update UK Residential Research | January 2018 South East London has benefitted from a significant facelift in recent years. A number of regeneration projects, including the redevelopment of ex-council estates, has not only transformed the local area, but has attracted in other developers. More affordable pricing compared with many other locations in London has also played its part. The prospects for South East London are bright, with plenty of residential developments raising the bar even further whilst also providing a more diverse choice for residents. Regeneration catalyst Pricing attraction Facelift boosts outlook South East London is a hive of residential Pricing has been critical in the residential The outlook for South East London is development activity. Almost 5,000 revolution in South East London. also bright. new private residential units are under Indeed pricing is so competitive relative While several of the major regeneration construction. There are also over 29,000 to many other parts of the capital, projects are completed or nearly private units in the planning pipeline or especially compared with north of the river, completed there are still others to come. unbuilt in existing developments, making it has meant that the residential product For example, Convoys Wharf has the it one of London’s most active residential developed has appealed to both residents potential to deliver around 3,500 homes development regions. within the area as well as people from and British Land plan to develop a similar Large regeneration projects are playing further afield. number at Canada Water. a key role in the delivery of much needed The competitively-priced Lewisham is But given the facelift that has already housing but are also vital in the uprating a prime example of where people have taken place and the enhanced perception and gentrification of many parts of moved within South East London to a more of South East London as a desirable and South East London. -

Annual Report and Accounts 2004/2005

THE BFI PRESENTSANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS 2004/2005 WWW.BFI.ORG.UK The bfi annual report 2004-2005 2 The British Film Institute at a glance 4 Director’s foreword 9 The bfi’s cultural commitment 13 Governors’ report 13 – 20 Reaching out (13) What you saw (13) Big screen, little screen (14) bfi online (14) Working with our partners (15) Where you saw it (16) Big, bigger, biggest (16) Accessibility (18) Festivals (19) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Reaching out 22 – 25 Looking after the past to enrich the future (24) Consciousness raising (25) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Film and TV heritage 26 – 27 Archive Spectacular The Mitchell & Kenyon Collection 28 – 31 Lifelong learning (30) Best practice (30) bfi National Library (30) Sight & Sound (31) bfi Publishing (31) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Lifelong learning 32 – 35 About the bfi (33) Summary of legal objectives (33) Partnerships and collaborations 36 – 42 How the bfi is governed (37) Governors (37/38) Methods of appointment (39) Organisational structure (40) Statement of Governors’ responsibilities (41) bfi Executive (42) Risk management statement 43 – 54 Financial review (44) Statement of financial activities (45) Consolidated and charity balance sheets (46) Consolidated cash flow statement (47) Reference details (52) Independent auditors’ report 55 – 74 Appendices The bfi annual report 2004-2005 The bfi annual report 2004-2005 The British Film Institute at a glance What we do How we did: The British Film .4 million Up 46% People saw a film distributed Visits to -

Neighbourhoods in England Rated E for Green Space, Friends of The

Neighbourhoods in England rated E for Green Space, Friends of the Earth, September 2020 Neighbourhood_Name Local_authority Marsh Barn & Widewater Adur Wick & Toddington Arun Littlehampton West and River Arun Bognor Regis Central Arun Kirkby Central Ashfield Washford & Stanhope Ashford Becontree Heath Barking and Dagenham Becontree West Barking and Dagenham Barking Central Barking and Dagenham Goresbrook & Scrattons Farm Barking and Dagenham Creekmouth & Barking Riverside Barking and Dagenham Gascoigne Estate & Roding Riverside Barking and Dagenham Becontree North Barking and Dagenham New Barnet West Barnet Woodside Park Barnet Edgware Central Barnet North Finchley Barnet Colney Hatch Barnet Grahame Park Barnet East Finchley Barnet Colindale Barnet Hendon Central Barnet Golders Green North Barnet Brent Cross & Staples Corner Barnet Cudworth Village Barnsley Abbotsmead & Salthouse Barrow-in-Furness Barrow Central Barrow-in-Furness Basildon Central & Pipps Hill Basildon Laindon Central Basildon Eversley Basildon Barstable Basildon Popley Basingstoke and Deane Winklebury & Rooksdown Basingstoke and Deane Oldfield Park West Bath and North East Somerset Odd Down Bath and North East Somerset Harpur Bedford Castle & Kingsway Bedford Queens Park Bedford Kempston West & South Bedford South Thamesmead Bexley Belvedere & Lessness Heath Bexley Erith East Bexley Lesnes Abbey Bexley Slade Green & Crayford Marshes Bexley Lesney Farm & Colyers East Bexley Old Oscott Birmingham Perry Beeches East Birmingham Castle Vale Birmingham Birchfield East Birmingham -

Ken Loach : Constructing Individuals

UNIVERSITE MICHEL DE MONTAIGNE – BORDEAUX III U.F.R D’ANGLAIS Ken Loach : Constructing Individuals Questions of existentialism, happiness, gender and individual / collective construction. TRAVAIL D’ETUDES ET DE RECHERCHES PRESENTE PAR ALEXANDRA BEAUFORT J UNIVERSITE MICHEL DE MONTAIGNE – BORDEAUX III U.F.R D’ANGLAIS Ken Loach : Constructing Individuals Questions of existentialism, happiness, gender and individual / collective construction. TRAVAIL D’ETUDES ET DE RECHERCHES PRESENTE PAR ALEXANDRA BEAUFORT Remerciements Je tiens à remercier: - Monsieur Joël Richard qui a accepté de diriger ce TER, pour sa confiance, son suivi et ses conseils; - Monsieur Jean François Baillon, pour son aide précieuse et sa disponibilité; - Monsieur Maurice Hugonin, pour son aide sur Aristote; - Messieurs Paul Burgess, Ken Allen, JF Buck, et les autres pour leur aide à la re- lecture; - Monsieur Fabrice Clerc, pour son soutien et son aide à la mise en page; - Tout le personnel de Parallax Pictures à Londres, pour leur gentillesse et leur compréhension; - Et enfin Ken Loach, pour son extrême gentillesse lors de l'interview, et surtout pour tous ses films, dont l'étude a toujours été passionnante et très enrichissante. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 I/ THE EXISTENTIALIST TREND IN LOACH'S FILMS. 3 1/ Against systematisation. 4 2/ The engagement of the self. 7 3/ Question of religion. 11 4/ Marxism and Existentialism: question of politics. 15 II/ THE PURSUIT OF HAPPINESS 19 1/ Learning to live 20 2/ The Aristotelian conception of citizenship. 23 3/ The organic city. 26 4/ Happiness and Socialization 29 III/ GENDER ISSUES. 33 1/ Is there a gender issue in Loach's movies? 34 2/ Out of home: from Cathy to Sarah 41 3/ Falling Standards, Fallen Males. -

2017 09 19 South Lambeth Estate

LB LAMBETH EQUALITY IMPACT ASSESSMENT August 2018 SOUTH LAMBETH ESTATE REGENERATION PROGRAMME www.ottawaystrategic.co.uk $es1hhqdb.docx 1 5-Dec-1810-Aug-18 Equality Impact Assessment Date August 2018 Sign-off path for EIA Head of Equalities (email [email protected]) Director (this must be a director not responsible for the service/policy subject to EIA) Strategic Director or Chief Exec Directorate Management Team (Children, Health and Adults, Corporate Resources, Neighbourhoods and Growth) Procurement Board Corporate EIA Panel Cabinet Title of Project, business area, Lambeth Housing Regeneration policy/strategy Programme Author Ottaway Strategic Management Ltd Job title, directorate Contact email and telephone Strategic Director Sponsor Publishing results EIA publishing date EIA review date Assessment sign off (name/job title): $es1hhqdb.docx 2 5-Dec-1810-Aug-18 LB Lambeth Equality Impact Assessment South Lambeth Estate Regeneration Programme Independently Reported by Ottaway Strategic Management ltd August 2018 Contents EIA Main Report 1 Executive Summary ................................................................................................. 4 2 Introduction and context ....................................................................................... 12 3 Summary of equalities evidence held by LB Lambeth ................................................ 17 4 Primary Research: Summary of Household EIA Survey Findings 2017 ........................ 22 5 Equality Impact Assessment .................................................................................. -

Paulo Renato Oliveira a Tradição Do Filme Documental E Realista

Universidade de Aveiro - Departamento de Línguas e Culturas 2001 Paulo Renato A Tradição do Filme Documental e Realista Britânico Oliveira dos anos 30 aos anos 70 Universidade de Aveiro - Departamento de Línguas e Culturas 2001 Paulo Renato A Tradição do Filme Documental e Realista Britânico Oliveira dos anos 30 aos anos 70 The British Documentary-Realist Film Tradition from the 1930s to the 1970s Dissertação apresentada à Universidade de Aveiro para cumprimento dos requisitos necessários à obtenção do grau de Mestre em Estudos Ingleses, realizada sob a orientação científica do Prof. Doutor Anthony Barker, Professor Associado do Departamento de Línguas e Culturas da Universidade de Aveiro O Júri Presidente Prof. Doutor Anthony David Barker, Professor Associado da Universidade de Aveiro (Orientador) Vogais Prof. Doutor Abílio Manuel Hernandez Ventura Cardoso, Professor Associado da Faculdade de Letras da Universidade de Coimbra Prof. Doutor Kenneth David Callahan, Professor Associado da Universidade de Aveiro Acknowledgements I want to express my gratitude to Professor Anthony Barker for all his enthusiastic support, encouragement, corrections and suggestions and, also because of all the insightful and enlighten discussions about Film. I would also like to thank Professors David Callahan and Aline Salgueiro for their contribution to my formation in Literature and Cultural Studies. This work would not have been possible without the cooperation of the British Film Institute. I am particularly indebted to the staff of the viewing services at the BFI, for providing me with some of Ken Loach’s plays to watch in their premises. Unfortunately these important television plays are not available to the general public and the only usable copies are kept at the BFI in London. -

From Free Cinema to British New Wave: a Story of Angry Young Men

SUPLEMENTO Ideas, I, 1 (2020) 51 From Free Cinema to British New Wave: A Story of Angry Young Men Diego Brodersen* Introduction In February 1956, a group of young film-makers premiered a programme of three documentary films at the National Film Theatre (now the BFI Southbank). Lorenza Mazzetti, Lindsay Anderson, Karel Reisz and Tony Richardson thought at the time that “no film can be too personal”, and vehemently said so in their brief but potent manifesto about Free Cinema. Their documentaries were not only personal, but aimed to show the real working class people in Britain, blending the realistic with the poetic. Three of them would establish themselves as some of the most inventive and irreverent British filmmakers of the 60s, creating iconoclastic works –both in subject matter and in form– such as Saturday Day and Sunday Morning, The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner and If… Those were the first significant steps of a New British Cinema. They were the Big Screen’s angry young men. What is British cinema? In my opinion, it means many different things. National cinemas are much more than only one idea. I would like to begin this presentation with this question because there have been different genres and types of films in British cinema since the beginning. So, for example, there was a kind of cinema that was very successful, not only in Britain but also in America: the films of the British Empire, the films about the Empire abroad, set in faraway places like India or Egypt. Such films celebrated the glory of the British Empire when the British Empire was almost ending. -

University of Huddersfield Repository

University of Huddersfield Repository Billam, Alistair It Always Rains on Sunday: Early Social Realism in Post-War British Cinema Original Citation Billam, Alistair (2018) It Always Rains on Sunday: Early Social Realism in Post-War British Cinema. Masters thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/34583/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ Submission in fulfilment of Masters by Research University of Huddersfield 2016 It Always Rains on Sunday: Early Social Realism in Post-War British Cinema Alistair Billam Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 3 Chapter 1: Ealing and post-war British cinema. ................................................................................... 12 Chapter 2: The community and social realism in It Always Rains on Sunday ...................................... 25 Chapter 3: Robert Hamer and It Always Rains on Sunday – the wider context. -

1,000 Films to See Before You Die Published in the Guardian, June 2007

1,000 Films to See Before You Die Published in The Guardian, June 2007 http://film.guardian.co.uk/1000films/0,,2108487,00.html Ace in the Hole (Billy Wilder, 1951) Prescient satire on news manipulation, with Kirk Douglas as a washed-up hack making the most of a story that falls into his lap. One of Wilder's nastiest, most cynical efforts, who can say he wasn't actually soft-pedalling? He certainly thought it was the best film he'd ever made. Ace Ventura: Pet Detective (Tom Shadyac, 1994) A goofy detective turns town upside-down in search of a missing dolphin - any old plot would have done for oven-ready megastar Jim Carrey. A ski-jump hairdo, a zillion impersonations, making his bum "talk" - Ace Ventura showcases Jim Carrey's near-rapturous gifts for physical comedy long before he became encumbered by notions of serious acting. An Actor's Revenge (Kon Ichikawa, 1963) Prolific Japanese director Ichikawa scored a bulls-eye with this beautifully stylized potboiler that took its cues from traditional Kabuki theatre. It's all ballasted by a terrific double performance from Kazuo Hasegawa both as the female-impersonator who has sworn vengeance for the death of his parents, and the raucous thief who helps him. The Addiction (Abel Ferrara, 1995) Ferrara's comic-horror vision of modern urban vampires is an underrated masterpiece, full- throatedly bizarre and offensive. The vampire takes blood from the innocent mortal and creates another vampire, condemned to an eternity of addiction and despair. Ferrara's mob movie The Funeral, released at the same time, had a similar vision of violence and humiliation. -

EARL CAMERON Sapphire

EARL CAMERON Sapphire Reuniting Cameron with director Basil Dearden after Pool of London, and hastened into production following the Notting Hill riots of summer 1958, Sapphire continued Dearden and producer Michael Relph’s valuable run of ‘social problem’ pictures, this time using a murder-mystery plot as a vehicle to sharply probe contemporary attitudes to race. Cameron’s role here is relatively small, but, playing the brother of the biracial murder victim of the title, the actor makes his mark in a couple of memorable scenes. Like Dearden’s later Victim (1961), Sapphire was scripted by the undervalued Janet Green. Alex Ramon, bfi.org.uk Sapphire is a graphic portrayal of ethnic tensions in 1950s London, much more widespread and malign than was represented in Dearden’s Pool of London (1951), eight years earlier. The film presents a multifaceted and frequently surprising portrait that involves not just ‘the usual suspects’, but is able to reveal underlying insecurities and fears of ordinary people. Sapphire is also notable for showing a successful, middle-class black community – unusual even in today’s British films. Dearden deftly manipulates tension with the drip-drip of revelations about the murdered girl’s life. Sapphire is at first assumed to be white, so the appearance of her black brother Dr Robbins (Earl Cameron) is genuinely astonishing, provoking involuntary reactions from those he meets, and ultimately exposing the real killer. Small incidents of civility and kindness, such as that by a small child on a scooter to Dr Robbins, add light to a very dark film. Earl Cameron reprises a role for which he was famous, of the decent and dignified black man, well aware of the burden of his colour. -

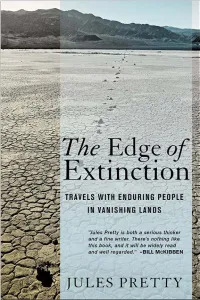

The Edge of Extinction: Travels with Enduring People in Vanishing

THE EDGE OF EXTINCTION Th e Edge of Extinction TRAVELS WITH ENDURING PEOPLE IN VANISHING LANDS M jules pretty Comstock Publishing Associates a division of Cornell University Press Ithaca and London Copyright © 2014 by Cornell University All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher. For information, address Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New York 14850. First published 2014 by Cornell University Press Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Pretty, Jules N., author. Th e Edge of extinction : travels with enduring people in vanishing lands / Jules Pretty. pages cm Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-0-8014-5330-4 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Nature—Eff ect of human beings on—Moral and ethical aspects. 2. Human beings—Eff ect of environment on—Moral and ethical aspects. I. Title. GF80.P73 2014 304.2—dc23 2014017464 Cornell University Press strives to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the fullest extent possible in the publishing of its books. Such materials include vegetable-based, low-VOC inks and acid-free papers that are recycled, totally chlorine-free, or partly composed of nonwood fi bers. For further information, visit our website at www.cornellpress.cornell.edu . Cloth printing 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 { iv } For My father, John Pretty (1932–2012), and mother, Susan and Gill, Freya, and Th eo Without my journey And without this spring I would have missed this dawn. -

The Grierson Effect

Copyright material – 9781844575398 Contents Acknowledgments . vii Notes on Contributors . ix Introduction . 1 Zoë Druick and Deane Williams 1 John Grierson and the United States . 13 Stephen Charbonneau 2 John Grierson and Russian Cinema: An Uneasy Dialogue . 29 Julia Vassilieva 3 To Play The Part That Was in Fact His/Her Own . 43 Brian Winston 4 Translating Grierson: Japan . 59 Abé Markus Nornes 5 A Social Poetics of Documentary: Grierson and the Scandinavian Documentary Tradition . 79 Ib Bondebjerg 6 The Griersonian Influence and Its Challenges: Malaya, Singapore, Hong Kong (1939–73) . 93 Ian Aitken 7 Grierson in Canada . 105 Zoë Druick 8 Imperial Relations with Polynesian Romantics: The John Grierson Effect in New Zealand . 121 Simon Sigley 9 The Grierson Cinema: Australia . 139 Deane Williams 10 John Grierson in India: The Films Division under the Influence? . 153 Camille Deprez Copyright material – 9781844575398 11 Grierson in Ireland . 169 Jerry White 12 White Fathers Hear Dark Voices? John Grierson and British Colonial Africa at the End of Empire . 187 Martin Stollery 13 Grierson, Afrikaner Nationalism and South Africa . 209 Keyan G. Tomaselli 14 Grierson and Latin America: Encounters, Dialogues and Legacies . 223 Mariano Mestman and María Luisa Ortega Select Bibliography . 239 Appendix: John Grierson Biographical Timeline . 245 Index . 249 Copyright material – 9781844575398 Introduction Zoë Druick and Deane Williams Documentary is cheap: it is, on all considerations of public accountancy, safe. If it fails for the theatres it may, by manipulation, be accommodated non-theatrically in one of half a dozen ways. Moreover, by reason of its cheapness, it permits a maximum amount of production and a maximum amount of directorial training against the future, on a limited sum.