Chapter One Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Introduction

1 Introduction 1.1 On the 18 May 2010 I was instructed by Jersey Heritage to carry out an independent assessment and produce a report on the architectural and historical interest of the 1952 Jersey Odeon Cinema. The building is listed as a Site of Special Interest (SSI). The brief included placing the Odeon into the wider UK context with reference to the development of cinemas generally. Photographs of the building were also requested. A full inspection was carried out on 6 July 2010. 1.2 I am a freelance consultant working in the planning, heritage and conservation sector. I am also currently employed by The Theatres Trust - The National Advisory Public Body for Theatres and a statutory consultee in the planning process within the UK - as its Planning and Heritage Adviser. An acknowledged expert in theatre and cinema buildings, I have over 20 years planning, architectural, urban design, conservation and regeneration experience. Previously I was Principal Urban Design and Conservation Officer for the London Borough of Hounslow dealing with listed buildings, conservation areas, planning and urban design issues and more recently (2008) working as a freelance conservation and design consultant for the London Borough of Hillingdon. I hold a degree in Estate Management and a Postgraduate Diploma in Historic Building Conservation from the Architectural Association (AA). I am a Chartered Town Planner (MRTPI) and a Full Member of the Institute of Historic Building Conservation (IHBC). I also serve on the Casework Committees of the Cinema Theatre Association, the Twentieth Century Society and the Victorian Society. 1.3 Dr Elain Harwood has agreed to edit this report. -

Aaaaannual Review

AAAAAnnual Review Front Cover: The Staffordshire Hoard (see page 27) Reproduced by permission of Birmingham Museum and Art Galleries See www.staffordshirehoard.org.uk Back Cover: Cluster of Quartz Crystals (see page 23) Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society Annual Report and Review 2010 th The 190 Annual Report of the Council at the close of the session 2009-10 Presented to the Annual Meeting held on 8th December 2010 and review of events and grants awarded THE LEEDS PHILOSOPHICAL AND LITERARY SOCIETY, founded in 1819, has played an important part in the cultural life of Leeds and the region. In the nineteenth century it was in the forefront of the intellectual life of the city, and established an important museum in its own premises in Park Row. The museum collection became the foundation of today’s City Museum when in 1921 the Society transferred the building and its contents to the Corporation of Leeds, at the same time reconstituting itself as a charitable limited company, a status it still enjoys today. Following bomb damage to the Park Row building in the Second World War, both Museum and Society moved to the City Museum building on The Headrow, where the Society continued to have its offices until the museum closed in 1998. The new Leeds City Museum, which opened in 2008, is now once again the home of the Society’s office. In 1936 the Society donated its library to the Brotherton Library of the University of Leeds, where it is available for consultation. Its archives are also housed there. The official charitable purpose of the Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society is (as newly defined in 1997) “To promote the advancement of science, literature and the arts in the City of Leeds and elsewhere, and to hold, give or provide for meetings, lectures, classes, and entertainments of a scientific, literary or artistic nature”. -

Public Space: the Management Dimension

INVESTIGATING PUBLIC SPACE MANAGEMENT The north terrace of the square is a heavily used pedestrian thoroughfare. During the day the pervasive presence of street performers adds to the liveliness of the space (Figure 10.6). As the day turns to afternoon and to evening and night the ambience becomes far more alcohol-based as drinks can be seen and smelt all over the square. By late night the area has built up to a raucous feel, which, on occasions, becomes unpleasant and intimidating. The gardens in the centre of the square are typical of London’s 10.6 Portrait artists in Leicester Square Georgian squares today, in that the layout of the square is community- and civil-minded with many benches and low walls for sitting on. Further symbolism is added through the two statues and four busts in the gardens. The Victorian and typically British elements are the grass, tall trees, flowerbeds and serpentine paths, all enclosed by iron railings. The architecture of the surrounding buildings speaks little of the rich history of Leicester Square for, like the gardens, it dates only as far back as the late nineteenth century. Cinema replaced theatre as the main form of entertainment in the 1930s, and still features prominently around the square. The square is dominated by the 1930s art deco Odeon Leicester Square on the east side, and more recently the Alhambra Theatre. On the north side there is the Empire Theatre, which was one of the first cinemas in London in 1896. On the south side is the Odeon West End, dating from the 1920s. -

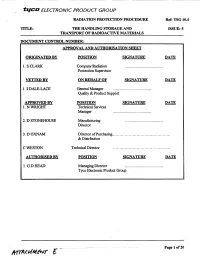

The Handling Storage and Transport

tiicA ELECTRONIC PRODUCT GROUP RADIATION PROTECTION PROCEDURE Ref: TSG 10.4 TITLE: THE HANDLING STORAGE AND ISSUE: 5 TRANSPORT OF RADIOACTIVE MATERIALS DOCUMENT CONTROL NUMBER: APPROVAL AND AUTHORISATION SHEET ORIGINATED BY POSITION SIGNATURE DA.TE 1. S CLARK Company Radiation Protection Supervisor VETTED BY ON BEHALF OF SIGNATURE DA ,TE 1. 1 DALE-LACE General Manager Quality & Product Support APPROVED BY POSITION SIGNATURE DAITE 1. N WRIGHT Technical Services Manager 2. D STONEHOUSE Manufacturing Director 3. D OXNAM Director of Purchasing ............................................ & Distribution C WESTON Technical Director AUTHORISED BY POSION SIGNATURE DA,TE 1. GD HEAD M anaging D irector ........................................ Tyco Electronic Product Group Page 1 of 20 -."+ c. .A .r. tZIca ELECTRONIC PRODUCT GROUP RADIATION PROTECTI(4• PROCEDURE Ref: TSG 10.4 TITLE: THE HANDLING STORAGE AND ISSUE: 5 TRANSPORT OF RADIOACTIVE MATERIALS CONTENTS LIST 1.0 Introduction 2.0 Scope 3.0 Responsibilities 4.0 Definitions 5.0 Procedure 5.1 Equipment & Materials 5.2 Health & Safety 5.2.1 Incident Reporting Procedure 5.3 Procedure 5.3.1 Despatch & Return of Finished Goods & Service Detectors to UK Destinations 5.3.2 Despatch of sample MF/Raft Detectors to UK destinations 5.3.3 Despatch of Finished Goods to International destinations 5.3.4 Packaging & Despatch of Waste (Scrap) or Detectors within UK 5.3.4.1 Removal from Customers Premises (all types) 5.3.4.2 Damaged Detectors (all types) 5.3.4.3 Packaging - Excepted 5.3.4.4 Packaging - I White, -

Report & Accounts of the Trustees

REPORT & ACCOUNTS OF THE TRUSTEES · 2016 REPORT & ACCOUNTS OF THE TRUSTEES · 2016 REFERENCE AND ADMINISTRATIVE INFORMATION The Garfield Weston Foundation is a general grant-giving charity endowed by the late W Garfield Weston and members of his family, which is registered with the Central Register of Charities, registration number 230260. The Foundation is recognised by the Inland Revenue as an approved charity for tax purposes, the reference number being X96978. Principal Office Weston Centre 10 Grosvenor Street · London W1K 4QY Trustees Guy H Weston, Chairman Camilla HW Dalglish Catrina A Hobhouse Jana R Khayat Sophia M Mason Eliza L Mitchell Melissa Murdoch W Galen Weston OC George G Weston Director Philippa Charles Secretary to the Trustees Janette Cattell Bankers Coutts & Co · 440 Strand · London WC2R 0QS Solicitors Slaughter and May 1 Bunhill Row · London EC1Y 8YY Auditors UHY Hacker Young LLP Quadrant House · 4 Thomas More Square · London E1W 1YW Fund Managers Investec 30 Gresham Street · London EC2V 7QN Unigestion Asia Pte. Ltd. 152 Beach Road · Suite #23-05/06 Gateway East · Singapore 189721 GARFiEld Weston FOUNdATiON 1 REPORT & ACCOUNTS OF THE TRUSTEES · 2016 Cumulative donations since 1958: £906 million Overall Spend for this year: 92% £58.7 grants made under £100k million ACHIEVEMENTS AND HIGHLIGHTS OF GARFIELD Weston FOUndation Growth in expenditure in Continued commitment the Community category: to fund core costs and up by 37% on last year to skill building £5.5million Supported + Continued growth 41% in expenditure in 50charities -

BULLETIN Vol 49 No 3 May / June 2015

CINEMA THEATRE ASSOCIATION BULLETIN www.cta-uk.org Vol 49 No 3 May / June 2015 The Odeon Trowbridge and the Picture House Morley. 2015 photos by David Simpson FROM YOUR EDITOR CINEMA THEATRE ASSOCIATION promoting serious interest in all aspects of cinema buildings It was good to meet some of you at the AGM and to put faces to ———————————————————— names. Thank you for all your kind comments about the Bulletin, Company limited by guarantee. Reg. No. 04428776. both in person at the AGM and also by letter and email. Registered address: 59 Harrowdene Gardens, Teddington, TW11 0DJ. Registered Charity No. 1100702. Directors are marked ‡ in list below. On the front page of the last Bulletin there were two ‘Cinema 100’ —————————————————————————————— plaques and I asked you where they were. The one for Sir David Lean PATRONS: Carol Gibbons Glenda Jackson is in pristine condition as it is indoors at the Brief Encounter exhibi- Sir Gerald Kaufman MP Lucinda Lambton tion at Carnforth Railway station in Lancashire. This was the easy —————————————————————————————— one and I expect many of you knew it already. The weathered one ANNUAL MEMBERSHIP SUBSCRIPTIONS Full Membership (UK) ...................................................... £25 (£29) was a little more difficult but an Internet search of the title Turn of Under 25s ......................................................................... £15 (£15) the Tide [eg: imdb.com] should have told you that it was filmed at Associate Membership (UK)............................................. £10 (£10) Robin Hood’s Bay in North Yorkshire. This is a very picturesque loca- Overseas (Europe Air Mail & World Surface Mail) ........... £32 (£37) tion and well worth a visit if you are in the area. -

June 2012 Newsletter

LICHFIELD & DISTRICT ORGANISTS’ ASSOCIATION Founded 1926 LDOA President: Martyn Rawles, FRCO JUNE 2012 NEWSLETTER RECENT LDOA VISITS Overhaul and reconditioning was carried out by Nicholson’s in 1955. It then seems there were further Saturday 21st April 2012 visit to St Peter’s, Maney, for changes carried out around 1974 by Tom Sheffield, with Chairman’s Afternoon and AGM extra stops being added to the Choir, the Clarinet moved from the Choir and changed to a Krummorn playable from The visit was at the kind invitation of our Chairman David the Great and Pedal, and the addition of a Trombone ex Gumbley, who is Organist and Director of Music at St Burton-on-Trent Town Hall. Peter’s Church, and the visit was combined with our 2012 AGM, matters arising from which are covered under In the 2006 rebuild by Nicholson’s, the main changes separate heading following this visit report. made were a Trumpet (2nd hand) on the Choir installed on a new chest, reversal of the 1974 change by restoring the The church was built on land purchased from Emmanuel Clarinet to the Choir, the wind pressure reduced on the College, and St Peter’s was consecrated on 28th June pedal Trombone, a new pedal board, and a 16 channel 1905 by the Bishop of Birmingham, the Rt Revd Charles computer capture system installed. Gore, gaining full parish status in 1907. As originally consecrated, the church was incomplete owing to lack of The very comprehensive 31 speaking stop full romantic funds, but in the late 1920’s it was decided to build the specification as it stands today is: final west bay and tower, the extension being consecrated by Bishop Barnes on 29th Sept 1935. -

The Fax Time Machine

This newsletter is the idea The Fax Time of the officers of the Halifax RL Heritage Lunch Club, and Machine club historian Andrew Hardcastle. All correspond- ence should be sent to, Chris Mitchell c/o Halifax Panthers RLFC The Shay Stadium, Shay Syke, Halifax HX1 2YT Year 1 Edition 6 July 2021 RFL Hall of Fame This month we turn to the Rugby Football League's Hall of Fame and its connection with Halifax. Sadly it's rather slender.The scheme was launched in 1988, when experts selected 9 original inductees, the players considered to be the very greatest in the game's history. They were Harold Wagstaff, Jim Sullivan, Albert Rosenfeld, Gus Risman, Jonty Parkin, Alex Murphy, Billy Boston, Brian Bevan and Billy Batten Not much of a Halifax connection there, you might think. But you'd be wrong. One of them actually turned out for us once, and later became first team coach for a couple of seasons. Just which one it was will be revealed lower down. Since 1988 another 19 names have joined these originals. This time there are two Halifax connections, though not as players. Roger Millward, add- ed in the year 2000, was our coach from May 1991 to December 1992, when he was replaced by our other Hall of Fame link, Malcolm Reilly, who joined the roll of honour in 2014 Roger Millward at Thrum Hall, 1992. Malcolm Reilly, Halifax coach, 1994. front row far left Should there be a Halifax player in the Hall of Fame? Karl Harrison, record If we were to start a campaign for one, who would it GB caps for a Halifax be? If we went for the player who's scored most tries player. -

'A British Empire of Their Own? Jewish Entrepreneurs in the British Film

‘A British Empire of Their Own? Jewish Entrepreneurs in the British Film Industry’ Andrew Spicer (University of the West of England) Introduction The importance of Jewish entrepreneurs in the development of Hollywood has long been recognized, notably in Neil Gabler’s classic study, An Empire of Their Own (1988). No comparable investigation and analysis of the Jewish presence in the British film industry has been conducted.1 This article provides a preliminary overview of the most significant Jewish entrepreneurs involved in British film culture from the early pioneers through to David Puttnam. I use the term ‘entrepreneur’ rather than ‘film-maker’ because I am analyzing film as an industry, thus excluding technical personnel, including directors.2 Space restrictions have meant the reluctant omission of Sidney Bernstein and Oscar Deutsch because the latter was engaged solely in cinema building and the former more significant in the development of commercial television.3 I have also confined myself to Jews born in the UK, thus excluding the Danziger brothers, Filippo del Giudice, Menahem Golan and Yoram Globus, Alexander Korda, Harry Saltzman and Max Schach.4 I should emphasize that my aim is to characterize the nature of the contribution of my chosen figures to the development of British cinema, not provide detailed career profiles.5 The idea that Jews controlled the British film industry surfaced most noticeably in the late 1930s when the undercurrent of anti-Semitic prejudice in British society took public forms; Isidore Ostrer, head of the giant Gaumont-British Picture Corporation (GBPC) was referred to in the House of Commons as an ‘unnaturalised alien’ (Low 1985: 243). -

Report on Strand 3A

Church Growth Research Programme Strand 3: Structures Cranmer Hall, St Johns College, Durham Report on Strand 3a Cathedrals, Greater Churches and the Growth of the Church October 2013 Canon John Holmes & Ben Kautzer 1 Contents Introduction Cathedrals are Growing p.5 Cathedrals are Growing Aims Limitations Methodology Overview Reflection Section 1 Background Section 1.1 The Narrative of Cathedral Growth p.8 1.1.1 Introduction 1.1.2 White Elephants? 1.1.3 Pilgrims and Tourists: Growth of Cathedral Visitors 1.1.4 Social change and church attendance 1.1.5 Growing signs 1.1.6 Spiritual Capital 1.1.7 Latest statistics Section 1.2 What are Cathedrals For? Cathedral Ministry and Mission in Context 1.2.1 Introduction 1.2.2 The Bishop’s seat 1.2.3 A Centre of worship 1.2.4 A centre of mission 1.2.5 Worship 1.2.6 Teaching 1.2.7 Service 1.2.8 Evangelism 1.2.9 Witness Section 2 Growing Cathedrals Section 2.1 Where is Cathedral Growth Happening? The Statistics p.16 2.1.1 Introduction 2.1.2 The Statistical Evidence for Cathedral Growth 2.1.3 Analysing the Data 2.1.3.1 Strengths of the data 2.1.3.2 Limitations of the data 2.1.4 Unpacking the Headline Statistics 2.1.4.1 Attendance Statistics by Province 2.1.4.2 Attendance Statistics by Region 2.1.4.3 Attendance Statistics by Cathedral Type 2.1.5 Church Growth and the Shifting Patterns of Cathedral Worship 2.1.5.1 Sunday Services 2.1.5.2 Weekday Services 2.1.6 Conclusion Section 2.2 Who is Attending Cathedral Services? The Worshipper Survey 2.2.1 Introduction 2.2.2 Towards a New Research Strategy 2 2.2.3 -

Index to Yorkshire Journal

Index to Yorkshire Journal A full index to the previous year’s issues was published in each Spring issue from 1994 to 2004. It would be extremely time consuming to combine these annual indexes into a single master index, so the annual indexes are individually reproduced in the remainder of this document. Fortunately it is relatively simple to find all references using the search function in your reader – usually this is invoked by pressing the Cntrl and F keys simultaneously. No index exists for the last three 2004 issues, as publication ceased at the end of this year, Each reference is indexed by the issue number (in bold type) followed by the page number. The issue numbers are: Spring Summer Autumn Winter 1993 1 2 3 4 1994 5 6 7 8 1995 9 10 11 12 1996 13 14 15 16 1997 17 18 19 20 1998 21 22 23 24 1999 25 26 27 28 2000 29 30 31 32 2001 33 34 35 36 2002 37 38 39 40 2003 - 41 42 43 2004 44 45 46 47 There was also a trial issue (Winter 1992) referenced by 0 The following suffixes have been used to identify the different types of material being referenced: a an illustration: drawing, painting, etc p photograph cp cover photograph v verse dv dialect verse ss short story (R) book review For example, 2 110p refers to a photograph on page 110 of the summer 1993 issue. Where no suffix is given, the reference is textual. Subject Index A Askrigg Kings Arms I 89-90 Addingham Atkinson, John Christopher Church of St Peter 3 68p Forty Years in a ‘Moorland Paris/1 Addlebrough 2 83p (r891), excpt 3 22 Adel auctions 4 I 15—17 Church of St John the Baptist -

Halifax DEAN CLOUGH

F Mill G Mill @ DEAN CLOUGH Halifax Offices To Let 137m2 (1476 ft2 ) to 7280m2 (78,368ft2 ) The stone-built mills at Dean Clough represent the zenith of a construction tradition.This quality has been actively reinforced in their re-development by adopting the best modern practice of design, refit and re-use. The highest quality materials have been incorporated including solid stone steps and landings, solid wood handrails, high quality doors and door furniture, stainless steel fittings and high specification carpets. These elements are matched by the quality of the mechanical and electrical design specification. Modern, energy efficient solutions for air quality and lighting fully comply with the rigorous requirements of the new Building Regulations. The end result is a product that can be maintained and operated at a highly competitive level in the long-term. It is a product that embodies the economic benefits of sustainability. F Mill and G Mill represent the acme of 20 years conversion experience using, and at times pioneering, contemporary design standards. Both mills offer an unmatched combination of quality and price. Facilities at both BCO Award Winning* mills include: Very Competitive Rates Highest quality materials and fittings Flexible Terms 24hr security and CCTV Scenic Lifts Long Term Design Features Spacious Environment On Site Management Low Service Charges Reserved and Pay&Display Car Parking Efficient Floor Plans Access Control Comfort Cooling *F Mill BCO North Region Award Winner, Refurbished Category 2005 G Mill BCO North Region Award Winner, Refurbished Category 2006 Let to Notes * Approximate dimension from underside of @ DEAN CLOUGH beams to apex of arched ceiling is 250 – 300mm.