Report on Strand 3A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Yorkshire Association of Change Ringers

The Yorkshire Association of Change Ringers Newsletter Autumn 2014 Issue Number 15 2015 Dates for your diary 7 February General Meeting, Leeds & District Branch 27 to 29 March The Harrogate Residential or 10 to 12 April Ringing Course 9 May AGM and Inter-Branch Striking Contest, Scarborough Branch 17 to 19 July The Storthes Hall Park Residential Ringing Course, Kirkburton 19 September General Meeting and Final of Sunday Service Bands Striking Contest, Sheffield & District Branch Also in September The White Rose Shield Striking Contest for 12-Bell Bands. In November The Snowdon Dinner Additionally, the Beverley & District Society is hosting the 2015 Central Council Meeting in Hull, 23 to 25 May. In 2015, in addition to the two residential Courses, the Education Committee plans to hold a Ringing Up & Down in Peal Course, a Tower Maintenance Course, a Conducting Course, a Handbells for Beginners Course and a Tune Ringing on Handbells Course. It also plans to hold a Course on Leadership in Ringing, with the intention of attracting younger ringers. 2 Yorkshire Association Newsletter Autumn 2014 EDITORIAL In the last edition about a year ago I said that we hoped the Newsletter might join the 21st Century in its presentation to members. This was discussed by the Association’s Standing Sub-Committee in February when it was decided that the Newsletter should continue in a paper format (as well as being on-line) so all members could readily browse through it at tower ringing. So this is what I’ve actioned. Holly Webster of York, originally from Easingwold, has very kindly filled the breach left by Jean Doman and has dealt with the layout and the new printing firm. -

Lancashire and the Legend of Robin Hood

Reconstructing the layout of the Town Fields of Lancaster Mike Derbyshire Although the Borough of Lancaster is known historically as an administrative and commercial centre, for much of its history agriculture dominated the town’s economy. In addition to providing the services associated with a market town, it did itself constitute a significant farming community. The purpose of the present paper is to examine the extent to which it is possible to reconstruct the layout of the town fields, in particular during the seventeenth century, and to locate fields mentioned in documents of that period. Lancaster is not a promising township in which to undertake an exercise of this kind. There is no map, such as a Tithe Map, showing field names in the township at a later date, which can be used as a basis for identifying the sites of fields mentioned in seventeenth century documents. The first objective was therefore to construct such a map as far as this is practicable, principally on the basis of nineteenth century sources. A preliminary task in preparing this map was the construction of an outline of field boundaries for recording the field names from nineteenth century sources (and also for presenting the information on field names from the seventeenth century). The most useful outline of field boundaries is provided by the Corn Rent plan of 1833. Although this does not provide field names, as do conventional Tithe Award plans, it does provide field boundaries at a date prior to the construction of the railways.1 Copies were scanned into a computer for manipulation, including the deletion of glebe land and the marsh, the deletion of areas of the moor shown as unenclosed or having the appearance of recent encroachments on Yates’s map of Lancashire of 17862 and the reconstruction of the field pattern prior to the building of the Lancaster canal. -

The Last Post Reveille

TTHHEE LLAASSTT PPOOSSTT It being the full story of the Lancaster Military Heritage Group War Memorial Project: With a pictorial journey around the local War Memorials With the Presentation of the Books of Honour The D Day and VE 2005 Celebrations The involvement of local Primary School Chidren Commonwealth War Graves in our area Together with RREEVVEEIILLLLEE a Data Disc containing The contents of the 26 Books of Honour The thirty essays written by relatives Other Associated Material (Sold Separately) The Book cover was designed and produced by the pupils from Scotforth St Pauls Primary School, Lancaster working with their artist in residence Carolyn Walker. It was the backdrop to the school's contribution to the "Field of Crosses" project described in Chapter 7 of this book. The whole now forms a permanent Garden of Remembrance in the school playground. The theme of the artwork is: “Remembrance (the poppies), Faith (the Cross) and Hope( the sunlight)”. Published by The Lancaster Military Heritage Group First Published February 2006 Copyright: James Dennis © 2006 ISBN: 0-9551935-0-8 Paperback ISBN: 978-0-95511935-0-7 Paperback Extracts from this Book, and the associated Data Disc, may be copied providing the copies are for individual and personal use only. Religious organisations and Schools may copy and use the information within their own establishments. Otherwise all rights are reserved. No part of this publication and the associated data disc may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the Editor. -

Report on Strand 3A

Church Growth Research Programme Strand 3: Structures Cranmer Hall, St Johns College, Durham Report on Strand 3a Cathedrals, Greater Churches and the Growth of the Church October 2013 Canon John Holmes & Ben Kautzer 1 Contents Introduction Cathedrals are Growing p.5 Cathedrals are Growing Aims Limitations Methodology Overview Reflection Section 1 Background Section 1.1 The Narrative of Cathedral Growth p.8 1.1.1 Introduction 1.1.2 White Elephants? 1.1.3 Pilgrims and Tourists: Growth of Cathedral Visitors 1.1.4 Social change and church attendance 1.1.5 Growing signs 1.1.6 Spiritual Capital 1.1.7 Latest statistics Section 1.2 What are Cathedrals For? Cathedral Ministry and Mission in Context 1.2.1 Introduction 1.2.2 The Bishop’s seat 1.2.3 A Centre of worship 1.2.4 A centre of mission 1.2.5 Worship 1.2.6 Teaching 1.2.7 Service 1.2.8 Evangelism 1.2.9 Witness Section 2 Growing Cathedrals Section 2.1 Where is Cathedral Growth Happening? The Statistics p.16 2.1.1 Introduction 2.1.2 The Statistical Evidence for Cathedral Growth 2.1.3 Analysing the Data 2.1.3.1 Strengths of the data 2.1.3.2 Limitations of the data 2.1.4 Unpacking the Headline Statistics 2.1.4.1 Attendance Statistics by Province 2.1.4.2 Attendance Statistics by Region 2.1.4.3 Attendance Statistics by Cathedral Type 2.1.5 Church Growth and the Shifting Patterns of Cathedral Worship 2.1.5.1 Sunday Services 2.1.5.2 Weekday Services 2.1.6 Conclusion Section 2.2 Who is Attending Cathedral Services? The Worshipper Survey 2.2.1 Introduction 2.2.2 Towards a New Research Strategy 2 2.2.3 -

Aspects of the Architectural History of Kirkwall Cathedral Malcolm Thurlby*

Proc Antiqc So Scot, (1997)7 12 , 855-8 Aspects of the architectural history of Kirkwall Cathedral Malcolm Thurlby* ABSTRACT This paper considers intendedthe Romanesque formthe of Kirkwallof eastend Cathedraland presents further evidence failurethe Romanesque for ofthe crossing, investigates exactthe natureof its rebuilding and that of select areas of the adjacent transepts, nave and choir. The extension of the eastern arm is examined with particular attention to the lavish main arcades and the form of the great east window. Their place medievalin architecture Britainin exploredis progressiveand and conservative elements building ofthe evaluatedare context building. the ofthe in use ofthe INTRODUCTION sequence Th f constructioeo t Magnus'S f o n s Cathedra t Kirkwalla l , Orkney comples i , d xan unusual. The basic chronology was established by MacGibbon & Ross (1896, 259-92) and the accoune Orkneth n i ty Inventory e Royath f o l Commissio e Ancienth d Historican o an nt l Monuments of Scotland (RCAHMS 1946,113-25)(illus 1 & 2). The Romanesque cathedral was begun by Earl Rognvald in 1137. Construction moved slowly westwards into the nave before the crossing was rebuilt in the Transitional style and at the same time modifications were made to the transepts includin erectioe gpresene th th f no t square eastern chapels. Shortly after thi sstara t wa sextensioe madth eastere n eo th befor f m no n ar e returnin nave e worgo t th t thi n .A k o s stage no reason was given for the remodelling of the crossing and transepts in the late 12th century. -

K Eeping in T Ouch

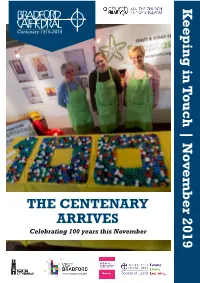

Keeping in Touch | November 2019 | November Touch in Keeping THE CENTENARY ARRIVES Celebrating 100 years this November Keeping in Touch Contents Dean Jerry: Centenary Year Top Five 04 Bradford Cathedral Mission 06 1 Stott Hill, Cathedral Services 09 Bradford, Centenary Prayer 10 West Yorkshire, New Readers licensed 11 Mothers’ Union 12 BD1 4EH Keep on Stitching in 2020 13 Diocese of Leeds news 13 (01274) 77 77 20 EcoExtravaganza 14 [email protected] We Are The Future 16 Augustiner-Kantorei Erfurt Tour 17 Church of England News 22 Find us online: Messy Advent | Lantern Parade 23 bradfordcathedral.org Photo Gallery 24 Christmas Cards 28 StPeterBradford Singing School 35 Coffee Concert: Robert Sudall 39 BfdCathedral Bishop Nick Baines Lecture 44 Tree Planting Day 46 Mixcloud mixcloud.com/ In the Media 50 BfdCathedral What’s On: November 2019 51 Regular Events 52 Erlang bradfordcathedral. Who’s Who 54 eventbrite.com Front page photo: Philip Lickley Deadline for the December issue: Wed 27th Nov 2019. Send your content to [email protected] View an online copy at issuu.com/bfdcathedral Autumn: The seasons change here at Bradford Cathedral as Autumn makes itself known in the Close. Front Page: Scraptastic mark our Centenary with a special 100 made from recycled bottle-tops. Dean Jerry: My Top Five Centenary Events What have been your top five Well, of course, there were lots of Centenary events? I was recently other things as well: Rowan Williams, reflecting on this year and there have Bishop Nick, the Archbishop of York, been so many great moments. For Icons, The Sixteen, Bradford On what it’s worth, here are my top five, Film, John Rutter, the Conversation in no particular order. -

Herefordshire News Sheet

CONTENTS ARS OFFICERS AND COMMITTEE FOR 1991 .................................................................... 2 PROGRAMME SEPTEMBER 1991 TO FEBRUARY 1992 ................................................... 3 EDITORIAL ........................................................................................................................... 3 MISCELLANY ....................................................................................................................... 4 BOOK REVIEW .................................................................................................................... 5 WORKERS EDUCATIONAL ASSOCIATION AND THE LOCAL HISTORY SOCIETIES OF HEREFORDSHIRE ............................................................................................................... 6 ANNUAL GARDEN PARTY .................................................................................................. 6 INDUSTRIAL ARCHAEOLOGY MEETING, 15TH MAY, 1991 ................................................ 7 A FIELD SURVEY IN KIMBOLTON ...................................................................................... 7 FIND OF A QUERNSTONE AT CRASWALL ...................................................................... 10 BOLSTONE PARISH CHURCH .......................................................................................... 11 REDUNDANT CHURCHES IN THE DIOCESE OF HEREFORD ........................................ 13 THE MILLS OF LEDBURY ................................................................................................. -

New Season of Bradford Cathedral Coffee Concerts Begins with Baritone Singer James Gaughan

Date: Thursday 9th January 2020 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE PRESS RELEASE New season of Bradford Cathedral Coffee Concerts begins with baritone singer James Gaughan The monthly Coffee Concerts held at Bradford Cathedral return on Tuesday 14th January when baritone singer James Gaughan performs a programme of music at 11am. Entry is free and refreshments are available from 10:30am. James Gaughan is an experienced soloist specialising in the song and concert repertoire. Based in York, he studies at the De Costa Academy of Singing with Michael De Costa. James gives lunchtime recitals throughout the year. Past performances include at Southwell Minster; Derby, Lincoln, 1 HOSPITALITY. FAITHFULNESS. WHOLENESS. [email protected] Bradford Cathedral, Stott Hill, Bradford, BD1 4EH www.bradfordcathedral.org T: 01274 777720 Sheffield and Wakefield Cathedrals; Emanuel United Reformed Church, Cambridge; Christ Church Harrogate; Hexham Abbey; Great Malvern Priory and others. He also performs regularly as a soloist with choirs and choral societies. Past performances include of Elijah (Mendelssohn); Stabat Mater (Astorga); Cantata 140 (Bach); Ein Deutsches Requiem (Brahms); Requiem (Fauré); Israel in Egypt (Handel); Paukenmesse (Haydn) and Messiah (Handel). James Gaughan: “The programme I’ve prepared is based around the poets, rather than around the composers. I think it’s become quite normal these days to have the historical concerts, where you go from composer to composer and knit them closely together. “What I’ve tried to do with this set-up is to place little sets from different periods of poetry, which means I can have quite a varied set of three songs which could theoretically be from three different centuries which gives a lot of variety for the audience, but still have some coherent link to it.” The monthly Coffee Concert programme continue with saxophonist Rob Burton in February, pianist Jill Crossland in March and Violin and Piano duo James and Alex Woodrow in April. -

Cathedral News

Cathedral News August 2019 – No. 688 From: The Dean We’ve recently gone through the process of Peer Review. After the Chapter had completed a lengthy self-evaluation questionnaire on matters of governance and finance and so on, three reviewers came from other cathedrals to mark our homework. Or rather, to bring an external perspective to bear, and help us refine our thinking about where we are heading as a cathedral. In spite of our natural wariness in advance, only to be expected given the amount of external scrutiny the cathedral has undergone in recent years, it was an encouraging experience. More of that, however, in a future Cathedral News. For now, I want to pick up on a comment made by all three reviewers. They came to us from Liverpool, Winchester, and Ely, and all expressed delight, and surprise, at the splendour of our cathedral: “We had no idea what a marvellous building it is!” For me, their observations provoked two questions... Is it because we all take the building for granted? Or is it because we’ve failed to tell our story effectively? I suspect there is truth behind both these questions. We all know how ‘distance lends enchantment to the view’; and the converse is also clearly true. It is not that familiarity necessarily breeds contempt, but you cannot live in a perpetual state of wonderment. Sir Simon Jenkins, the author of all those books on beautiful houses and railway stations and churches and cathedrals, told of his visit to Exeter: “I came into the cathedral and sat in silence for half an hour, overwhelmed by the beauty of the place.” I have the benefit of being in the cathedral every day, and will often speak of how our vaulted ceiling lifts my heart daily to heaven. -

Brian Knight

STRATEGY, MISSION AND PEOPLE IN A RURAL DIOCESE A CRITICAL EXAMINATION OF THE DIOCESE OF GLOUCESTER 1863-1923 BRIAN KNIGHT A thesis submitted to the University of Gloucestershire in accordance with the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Arts and Humanities August, 2002 11 Strategy, Mission and People in a Rural Diocese A critical examination of the Diocese of Gloucester 1863-1923 Abstract A study of the relationship between the people of Gloucestershire and the Church of England diocese of Gloucester under two bishops, Charles John Ellicott and Edgar Charles Sumner Gibson who presided over a mainly rural diocese, predominantly of small parishes with populations under 2,000. Drawing largely on reports and statistics from individual parishes, the study recalls an era in which the class structure was a dominant factor. The framework of the diocese, with its small villages, many of them presided over by a squire, helped to perpetuate a quasi-feudal system which made sharp distinctions between leaders and led. It is shown how for most of this period Church leaders deliberately chose to ally themselves with the power and influence of the wealthy and cultured levels of society and ostensibly to further their interests. The consequence was that they failed to understand and alienated a large proportion of the lower orders, who were effectively excluded from any involvement in the Church's affairs. Both bishops over-estimated the influence of the Church on the general population but with the twentieth century came the realisation that the working man and women of all classes had qualities which could be adapted to the Church's service and a wider lay involvement was strongly encouraged. -

Eternal Light: a Requiem

Eternal Light: A Requiem 2008 Theatre Royal, Bath Sadlers Wells, London Forum Theatre, Malvern Theatre Royal, Plymouth St John’s Smiths Square, London The Lowry, Salford Wycombe Swan, High Wycombe Theatre Royal, Norwich Festival Theatre, Edinburgh 2009 Cymru, Llandudno Hall for Cornwall, Truro Snape Maltings Theatre Royal, Brighton Eden Court, Inverness Clwyd Theatre, Cymru, Mold Theatre Royal, Newcastle Birmingham Hippodrome, Birmingham Tewkesbury Abbey, Tewkesbury Guildhall, Plymouth Wells Cathedral, Wells Newcastle University, Australia Grand Theatre, Leeds Leisure Centre, Thame Hertogenbosch, The Netherlands St Peter’s Church, Plymouth St John the Baptist Church, Barnstaple All Saints Church, Swansea Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford All Saints Church, Douglas, Isle of Man Parish Church, Stockton State Hall, Heathfield, East Sussex Methodist Church, Belfast Methodist Central Hall, Coventry St Lukes United Methodist Church, Houston TX, USA St James the Great Church, Littlehampton St John’s Church, Old Coulsdon St Bede’s Roman Catholic Church, Basingstoke Tewskesbury Abbey St Mary’s Church, Bury St Edmunds St James, Exeter 2010 Leisure Centre, Billingshurst St Michael’s & All Angels Church, Turnham Green, London St Peters Church, Ealing, London Lady Eleanor Hollis School, Hampton All Saints Church, Putney, London Easterbrook Hall, Dumfries Waterfront Hall, Belfast First United Church, Mooretown NJ, USA Symphony Hall, Birmingham St James Piccadilly, London The Sage, Gateshead Cadogan Hall, London St Saviour’s Church, Brockenhurst St Albans -

Peter Davenport

BATH ABBEY Peter Davenport There is no clear evidence as to when the first Christians reached Bath. We know they were here in the 3rd century when they are mentioned in a curse from the Sacred Spring of Sulis Minerva. That curse, employing a variation of what was obviously a legalistic formula, (' .. whether slave or free, Christian or pagan . ') implies that Christians were a recognised part of local society. They may not always have been a very respectable part of society, however. It may be that the local centurion Gaius Severius Emeritus was referring to them when he caused an altar to be erected in the Temple Precinct recording the rededication of this 'holy spot, wrecked by insolent hands'. Although Christianity, having become the majority religion by the end of the Roman period, survived in the areas held by the Britons against the invading Saxons, it does not seem to have done so around Bath after the capture of the region in 577. The Severn was the limit of the territory nominally controlled by the British (or Welsh) bishops that Augustine so disastrously failed to win over to his mission in 598. After the missionary work of St. Augustine and his successors Christianity was again established, especially through the conversion of the Saxon kings (with the expectation that their loyal subjects would emulate them). It is against this background that we can begin our account of Bath's Abbey. The Saxon Abbey The earliest document that the Abbey can produce is a charter dated 675, granted by King Osric of the Hwicce, a sub-grouping 2 PETER DAVENPORT of the Kingdom of Mercia.