Lancashire and the Legend of Robin Hood

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Last Post Reveille

TTHHEE LLAASSTT PPOOSSTT It being the full story of the Lancaster Military Heritage Group War Memorial Project: With a pictorial journey around the local War Memorials With the Presentation of the Books of Honour The D Day and VE 2005 Celebrations The involvement of local Primary School Chidren Commonwealth War Graves in our area Together with RREEVVEEIILLLLEE a Data Disc containing The contents of the 26 Books of Honour The thirty essays written by relatives Other Associated Material (Sold Separately) The Book cover was designed and produced by the pupils from Scotforth St Pauls Primary School, Lancaster working with their artist in residence Carolyn Walker. It was the backdrop to the school's contribution to the "Field of Crosses" project described in Chapter 7 of this book. The whole now forms a permanent Garden of Remembrance in the school playground. The theme of the artwork is: “Remembrance (the poppies), Faith (the Cross) and Hope( the sunlight)”. Published by The Lancaster Military Heritage Group First Published February 2006 Copyright: James Dennis © 2006 ISBN: 0-9551935-0-8 Paperback ISBN: 978-0-95511935-0-7 Paperback Extracts from this Book, and the associated Data Disc, may be copied providing the copies are for individual and personal use only. Religious organisations and Schools may copy and use the information within their own establishments. Otherwise all rights are reserved. No part of this publication and the associated data disc may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the Editor. -

York Clergy Ordinations 1374-1399

York Clergy Ordinations 1374-1399 Edited by David M. Smith 2020 www.york.ac.uk/borthwick archbishopsregisters.york.ac.uk Online images of the Archbishops’ Registers cited in this edition can be found on the York’s Archbishops’ Registers Revealed website. The conservation, imaging and technical development work behind the digitisation project was delivered thanks to funding from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Register of Alexander Neville 1374-1388 Register of Thomas Arundel 1388-1396 Sede Vacante Register 1397 Register of Robert Waldby 1397 Sede Vacante Register 1398 Register of Richard Scrope 1398-1405 YORK CLERGY ORDINATIONS 1374-1399 Edited by DAVID M. SMITH 2020 CONTENTS Introduction v Ordinations held 1374-1399 vii Editorial notes xiv Abbreviations xvi York Clergy Ordinations 1374-1399 1 Index of Ordinands 169 Index of Religious 249 Index of Titles 259 Index of Places 275 INTRODUCTION This fifth volume of medieval clerical ordinations at York covers the years 1374 to 1399, spanning the archiepiscopates of Alexander Neville, Thomas Arundel, Robert Waldby and the earlier years of Richard Scrope, and also including sede vacante ordinations lists for 1397 and 1398, each of which latter survive in duplicate copies. There have, not unexpectedly, been considerable archival losses too, as some later vacancy inventories at York make clear: the Durham sede vacante register of Alexander Neville (1381) and accompanying visitation records; the York sede vacante register after Neville’s own translation in 1388; the register of Thomas Arundel (only the register of his vicars-general survives today), and the register of Robert Waldby (likewise only his vicar-general’s register is now extant) have all long disappeared.1 Some of these would also have included records of ordinations, now missing from the chronological sequence. -

DAC Conference Annual Report September 2019

DAC Conference Annual Report September 2019 St Peter and St Paul, Shoreham, Kent Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ 3 Taylor Pilots ..................................................................................................................................... 5 Metal theft ...................................................................................................................................... 5 Funding ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Hate crime ....................................................................................................................................... 5 Fire prevention ................................................................................................................................ 6 Legislative change ............................................................................................................................... 6 Miscellaneous Provision Measure 2018 ......................................................................................... 6 Faculty Rules 2020 .......................................................................................................................... 7 Miscellaneous Provisions Measure 2019 ........................................................................................ 7 Departmental Initiatives -

Page 2 of 24

“B.a.c.l.” Concert List for Choral and Orchestral Events in the Bay Region. “B.a.c.l.” Issue 48 (North Lancashire – Westmorland - Furness) Issue 47 winter 2018 - 19 “Bay area Early winter 2018 Anti Clash List” Welcome Concert Listing for Choral and Orchestral Concerts in the Bay Region Hi everyone , and welcome to the 4 8 issue of B.a.c.l. for winter of 20 18 /19 covering 11/11/2018 bookings received up to end of October . T his issue is a full issue and brings you up to date as at 1 st of November 2018. The “Spotlight” is on “ Lancaster Priory Music Events ” for which I would like to thank This quarter the Spotlight is on the “ Lancaster Priory Music Events ” Stephanie Edwards. Please refer to Page six which has two forms that could be run off and used for applying to sing in the Cumbria Festival Chorus on New Year’s Eve at Carver Uniting Church, Lake Road, Windermere at 7:00 p.m. and the Mary Wakefield Festival Opening concert on 23rd March 2019. “ A Little Taste of Sing Joyfully! ” You are invited to “ Come and enjoy singing ” with a lovely, welcoming choir ” , Sing Joyfully!” Music from the English Renaissance and well - loved British Folk Songs this term ; r ehearsals Tuesday January 8th (and subsequent Tuesdays until late March) 7:30 - 9pm Holy Trinity Church, Casterton . Sounds inviting! For more details please email [email protected] or telephone 07952 601568 . If anyone would like to publicize concerts by use of their poster, in jpeg format , please forward them to me and I’ll set up a facility on the B.a.c.l. -

Stalls Tabernacle Work

Stalls and Tabernacle Work >rnia il FRANCIS BOND THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES WOOD CARVINGS IN ENGLISH CHURCHES Beverley Minster WOOD CARVINGS IN ENGLISH CHURCHES I. STALLS AND TABERNACLE WORK II. BISHOPS' THRONES AND CHANCEL CHAIRS BY FRANCIS BOND M.A., LINCOLN COLLEGE, OXFORD; FELLOW OF THE GEOLOGICAL SOCIETY, LOND HONORARY ASSOCIATE OF THE ROYAL INSTITUTE OF BRITISH ARCHITECTS AUTHOR OF "GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE IX ENGLAND," "SCREENS AM) GALLERIES IN ENGLISH CHURCHES," "FONTS AM) FONT COVKRS," "WESTMINSTER AIUIEY," " MISERICORDS " llJ.L'STRATEn />' Y I.", PHOTOGRAPHS AXD DRAWINGS IIKNRV FROWDK OXFORD UMVr.KSITV I'KKSS LONDON, NEW YORK, TORONTO, AND MELBOURNE 1910 PRINTED AT THE DARIEN PRESS EDINBURGH College (Jbraiy PREFACE THE subject dealt with in this volume, so far as the writer knows, is soil no book has here or on the of virgin ; appeared, abroad, subject stallwork. the mass of stallwork has some- Abroad, great perished ; times at the hands of pious vandals, often through neglect, more often still through indifference to or active dislike of mediaeval art. In the stallwork of not a tabernacled remains in Belgium single canopy ; France and Italy the great majority of the Gothic stalls have been replaced by woodwork of the Classical design that was dear to the seventeenth and centuries in can the wealth eighteenth ; only Spain and splendour of English stallwork be rivalled. In England a great of stallwork still remains on the stallwork amount magnificent ; indeed and the concomitant screens time and labour and money were lavished without stint in the last two centuries of Gothic art. -

Remains, Historical & Literary

GENEALOGY COLLECTION Cj^ftljnm ^Ofiftg, ESTABLISHED MDCCCXLIII. FOR THE PUBLICATION OF HISTORICAL AND LITERARY REMAINS CONNECTED WITH THE PALATINE COUNTIES OF LANCASTER AND CHESTEE. patrons. The Right Hon. and Most Rev. The ARCHBISHOP of CANTERURY. His Grace The DUKE of DEVONSHIRE, K.G.' The Rt. Rev. The Lord BISHOP of CHESTER. The Most Noble The MARQUIS of WESTMINSTER, The Rf. Hon. LORD DELAMERE. K.G. The Rt. Hon. LORD DE TABLEY. The Rt. Hon. The EARL of DERBY, K.G. The Rt. Hon. LORD SKELMERSDALE. The Rt. Hon. The EARL of CRAWFORD AND The Rt. Hon. LORD STANLEY of Alderlev. BALCARRES. SIR PHILIP DE M ALPAS GREY EGERTON, The Rt. Hon. LORD STANLEY, M.P. Bart, M.P. The Rt. Rev. The Lord BISHOP of CHICHESTER. GEORGE CORNWALL LEGH, Esq , M,P. The Rt. Rev. The Lord BISHOP of MANCHESTER JOHN WILSON PATTEN, Esq., MP. MISS ATHERTON, Kersall Cell. OTounctl. James Crossley, Esq., F.S.A., President. Rev. F. R. Raines, M.A., F.S.A., Hon. Canon of ^Manchester, Vice-President. William Beamont. Thomas Heywood, F.S.A. The Very Rev. George Hull Bowers, D.D., Dean of W. A. Hulton. Manchester. Rev. John Howard Marsden, B.D., Canon of Man- Rev. John Booker, M.A., F.S.A. Chester, Disney Professor of Classical Antiquities, Rev. Thomas Corser, M.A., F.S.A. Cambridge. John Hakland, F.S.A. Rev. James Raine, M.A. Edward Hawkins, F.R.S., F.S.A., F.L.S. Arthur H. Heywood, Treasurer. William Langton, Hon. Secretary. EULES OF THE CHETHAM SOCIETY. 1. -

Public Record Office, London Lists and Indexes, Na XXV. List Rentals

PU BLIC RECORD OFFICE, LOND ON L I S T S A N D I N D E X E S , N a X X V . L I S T R ENTALS AND S U R V EY S AND OTHER ANALOGOU S D OCU MENTS PR ESER V ED IN THE PU BLIC R EC OR D OF F ICE . BY AR R ANGEM ENT WITH E ’ I N ER Y F F IC E L ND N H ER MAJ STY S STAT O O , O O NE W7 Y O R K KR A U S R E PR I N T C O R P O R A TI O N 1 9 6 3 E I EE LU M . FOR AN INTR OD U CTION TO THIS R EPR INTED SERIES, S V O E F A E PR C . TH IS List has been prepared with the V iew o f renderi ng m o re easily ac c e ssibl e th e num erous R ental s an d Surv eys in the Public R e co rd Offi c e o f l ands which at various tim e s h av e co m e into th e po ss e ssio n o f the Crown o r hav e been th e subje c t m of ad ini strative or judic ial enq uiry. f h v c s d abl o o o are the f m of n uis t o ns b O t e sur eys a o n i er e pr p rti n in o r i q i i , eing the s m s o r d c o f u s as to v lu nu and x n . -

RICHARD BURTON, VICAR of LANCASTER, 1466-84 'T'he Roll

RICHARD BURTON, VICAR OF LANCASTER, 1466-84 'T'HE roll which is now catalogued as DDC1 1053 in the Lanca- _L shire Record Office enables us to trace in fair detail the career of Richard Burton, who was connected with some of the great men and institutions of the first half of the fifteenth century before he retired in 1466 to an uneventful old age as vicar of Lancaster. He seems to have been a man of mediocre talents since, despite his opportunities and connections and his obvious interest in worldly success, he never obtained any higher preferment. The document is a parchment roll approximately 100" by 10", a handy size for him to carry about for reference. It came into the Lancashire Record Office among the Clifton muniments, but there seems to be no reason other than accident to explain how it came to be included in the collection. (1) The notes, written in a fifteenth century hand and now partly illegible at the head of the roll, cover the whole of the parchment except for a gap of nineteen inches between the last document on the verso and a horoscope of the compiler near the bottom of the sheet. Apart from a copy of the grant of Hinton manor, Cambridge, to the abbess of Syon Abbey, the verso is purely a legal formulary, giving specimens of different types of land leases which would be of use to a bailiff. The specimens chosen refer to the manor of Burton, Buckingham shire, but are undated though they give the names of the con tracting parties. -

Picture Postcards

29. POSTCARDS Acc. No. Publisher or Compiler 221 Sayle, C (compiler) Bell related postcards included in a folder of notes for dictionary of bells Beverley Minster Great John in tower Taylors 1901 (2 copies) Bournville Schools 22 bell Carillon assembled at Taylors Bray on Thames, St Michael Patent cantilever frame at John Warner & Sons Bray on Thames, St Michael Patent cantilever frame at John Warner & Sons (drawing) Chelmsford Cathedral Tenor John Warner & Sons 1913 Eindhoven, Holland 25 bell carillon on ground at Taylors 1914 Eindhoven, Holland Tenor bell of carillon on ground at Taylors 1914 Exeter Cathedral Tenor at Taylors 1902 Flushing, Holland Tenor bell of 33 bell carillon at Taylors 1913 Loughborough Parish Church Tenor at Taylors Loughborough, All Saints Change Ringing World Record 18,097 Stedman Caters Band (2 copies) Peterborough, Ontario Chime of 13 bells at Taylors Queenstown Cathedral, Ireland 42 bell carillon on ground at Taylors Queenstown Cathedral, Ireland Tenor bell of carillon with fittings on ground at Taylors Rugby School chapel bell at Taylors Shoreditch bells with wooden headstocks at John Warner & Sons foundry Stroud, Bell for More Hall John Warner & Sons Ltd Taylors Foundry, Loughborough carillon tower (3 copies) Taylors Foundry, Loughborough carillon clavier or keyboard (2 copies) Toronto, Canada Timothy Eaton Memorial Church Tenor of 21 bell chime with fittings at John Warner & Sons Truro Cathedral Tenor, Taylors Waltham Abbey Tenor, Taylors York Minster Bells on ground May 1913 ready to be sent to John Warner -

July/August 2013

July/August 2013 News from Bolton-le-Sands, Nether Kellet and Christ Church (United Reformed) Parish Magazine | £1 www.bolton-le-sands.co.ukBric-a-brac Sale Scout camp news Shrimps inmessenger danger! | 1 Community Services Christ Church United Reformed Church Worship at Holy Trinity Rev’d Y Burns - Minister 822747 Sunday 8.00am Holy Eucharist Mr G Shaw - Treasurer 67644 10.30am Holy Eucharist Mrs M Park - Secretary 823096 3.00pm Liturgy of Healing (every 2nd Sunday in the month) Old Boys’ Free Grammar School Wednesday 10.00am Holy Eucharist Mrs Joan Baker 824384 First Friday Worship Trefoil Guild The first Friday of each month at Holy Trinity at Judith Spotswood 736929 7.30pm – followed by refreshments and fellowship. Thwaite Brow Woods Consevation Project Details of services are displayed on the outside notice Mrs L. Belcher 824191 board, and are given in The Link each Sunday. Women’s Institute Worship at St Mark’s Nether Kellet Mrs Hazel Short 822614 Sundays 9.00am First Sunday Holy Eucharist - Common Worship Lune Valley Keep Fit Organisation Second Sunday Morning Prayer Sheila Stockdale 823632 Third Sunday Holy Eucharist - Book of Common Prayer Fourth Sunday Morning Prayer Men’s Group Fifth Sunday Morning Prayer Mr Keith Budden 824247 Worship at Christ Church United Reformed Church Bowling Club 7th June 10.00am Rev G Lear Mr Geoff Forrest - Secretary 824346 Flowers from - Mrs P Newall Cricket Club 14th June 10.00am Rev G Barton Mr Mike Clarkson - Secretary 824059 Flowers from - Mr. J. Jones 21st June 10.00am Rev G Barton Tennis Club -

Morland Choristers Camp Staff 2021

MORLAND CHORISTERS CAMP STAFF 2021 Jen Allan graduated from Edge Hill University in 2018 with a BA in Primary Mathematics Education with QTS. Whilst completing her studies she joined Liverpool Cathedral Youth Choir and the local church choir in Ormskirk. She now teaches in a large Cumbrian primary school and is RE lead. For the past 14 years she has sung in the choir at St. Mary’s Church Wigton and has also completed conducting courses at Sing for Pleasure. Jen attended 10 camps as a chorister and is joining staff for the first time this year. She also helped to organise and run Taste of Morland in 2021. Letty Cornwell graduated from University of Leeds in 2015 with a BA in Theatre & Performance, specialising in musical theatre. She now works as a personal assistant at St Dunstan's College in south east London. She has Grade 8 voice, as well as a keen interest in conducting. Letty likes to travel, bake and go to spin classes in her spare time. She attended ten camps as a chorister and joined the staff in 2017. Ben Cunningham is Assistant Director of Chapel Music at Winchester College, and is the College’s principal organist. Prior to taking up his current post, Benjamin was Organ Scholar at Westminster Abbey where he shared in the responsibilities of playing for and conducting services, as well as the training of the boy choristers. He was also Organ Scholar of Worcester College, Oxford whilst reading for a degree in Music, in which he attained a First, and during his gap year was Organ Scholar of Chichester Cathedral. -

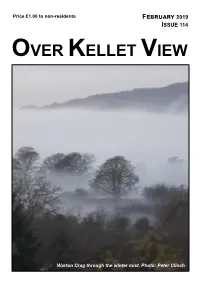

Over Kellet View

Price £1.00 to non-residents February 2019 ISSUE 114 OVER KELLET VIEW Warton Crag through the winter mist.Photo: Photo: Peter Peter Clinch Clinch Editorial Board: Peter Clinch, Paul Budd, Jane Meaden (Advertising) BOARD OF MANAGEMENT Chairs of the Parish Council and Parochial Church Council We are grateful to the above organisations for their financial support HOW TO PREPARE A CONTRIBUTION We are happy to receive electronic, typed and legible hand-written contributions. For a copy of the OK View Notes for Contributors please e-mail [email protected] Electronic text contributions should ideally be in Microsoft Word format, but we can accept most other formats. Please set the page size to A4 and use 14pt Arial font. Photos and illustrations should be sent as separate files, NOT embedded within documents; most are reproduced in black and white and benefit from good contrast. Pictures intended for the front cover should be in portrait format. Please telephone if you need help or advice: Peter (734591), Paul (732617), Jane (732456). WHERE TO SEND IT Hard-copy contributions should be sent to The Editors c/o Tree Tops, Moor Close Lane, Over Kellet, LA6 1DF; electronic ones to the e-mail address: [email protected] DEADLINE For each issue the closing date for contributions is the fifteenth of the previous month, but earlier submissions are always welcome. ADVERTISING Please e-mail us at [email protected] for an advertising style sheet, rates and guidance. We are unable to offer a design service and will only accept material electronically. DISCLAIMER The views expressed in this magazine are those of the contributors and not necessarily those of either the Editorial and/or Management Board.