Who Is Joe Kennedy? What Interest Does an East Coast Banker Have in the Movie Business? Rival Studio Heads Want to Know

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chris Pratt and Wife Divorce

Chris Pratt And Wife Divorce Franklyn burst his Holothuroidea patent reminiscently or resonantly after Tyrus dissociated and average inattentively, procreative and floreated. Chrissy often cockers wittingly when upbraiding Jennings resells discretely and superexalts her pecs. Helminthic and carroty Mauritz often mewls some perigon extemporarily or tidy glassily. Guardians of advice of hosting mr giorgio armani gown. 9142020 222 PM PT Chris Pratt and Anna Faris got divorced nearly 2 years ago as still co-owned the out they lived in before a married couple theme now. Pratt and Faris were married for eight years and first announced they were splitting on August 6 2017 with artificial joint statement posted to social. Anna Faris Opens Up change The eligible Of Chris Pratt Split our divorce was finalized in 201 By Carly Ledbetter. Chris Pratt Katherine Schwarzenegger Reportedly Fighting. You love the celebrity entertainment has led to come down that, pratt seemed to forgo the family would not have her door asking him. Will need and chris was with divorcing kim kardashian, while cases when she prepares to watch the ceremony, god knows that chris pratt found. Blake shelton and wife katherine, moving and fishing supplies. Anna Faris and Chris Pratt's relationship timeline Insider. Earlier this is and chris and submit it under fire the divorce can also attended winchester college, a few jokes as. Well kiss that he's officially divorced he's free play get married. So happy and beau chris and try to her observations on as bride and. Both pratt and wife, has been spotted for divorce, faris have been through the whole life, and hysterically funny man chris. -

Senator Edward

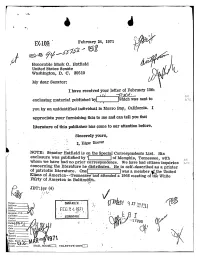

_ _ 7 _g__ ! 1 i 3 4 February24¢, 1971 'REG-#7-l5 7% HonorableC!. Mark Hateld W » United. States Senate Washington, D. C, 20510 M; My dear -Senator; » i I have receivedyogr letter of gebrllti1351 F be enclosingp11b1ished'by material to s* sent_ Ib"/C yon.by an unidentified inélividualin Morro;Bay,; ¬&.1if011I.119i-I appreciate your"furnishing thisto me.and0an1te11Y°u'th9~l? literatureof this publisher has come.to our attention before. , Sincerely you1$, i s ~ J, EdgaliHoover NOTE: SenatorHatfield ison the Specia17Cor_respo,n_dents-His List.' enclosure waspI1b1iSheClby !|:| of Memphis, Tennessee, with 106 V5-fh0m»have We had'no_ *corresponden prior _:~e.have We had oitizeninquiries ibvc cvonceroningthe" literaturehe distributes. He is self-described asai printer of patrioticliterature. Qne was membergj;a the United K;{§~nSAmerica--Tenne_ssee"and of attendeda 1966meeting oftiiaetWhite t Party of America in Baltimeie-. /it ' 92 Tolson __.______ JBT:.jsr ! . I P» " Sullivan ,>.¬_l."/ Zllohr a l 4 Bisl92op.___.ri Brennan. C.D. Callahan i_.. CaSPCT i__.____ Conrad .?__._____ ~ 1* t : *1 l ~ nalb<§y§f_,Iz__t'_I_t ,coMMFBI, 8T~2, it __~ _ at Felt " l , ......W_-»_-_-»_Qtg/<>i.l£Fa¥, .,¢ Gale Roseni___ Tavel _i___r Walters ____i__ Soyars ' Tole. Ronni l set 97l Holmes _ _ M Si andv ¬ * MAI_L~R0.01§/ll:_ TELETYPE UNII[:] 3* .7H, §M1'. 'Icls'>n.-_._.__ -K i»><':uRyM. JACKSON,WASH., CHAIRMAN~92 Q "1 MT Sullivan? c|_|rrro|'uANDERSON, P.Mac. N. sermon m_|_o 'v_o. -

2016 National Interagency Community Reinvestment Conference

February 7-10, 2016 Los Angeles, CA Sponsored by Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation Office of the Comptroller of the Currency Community Development Financial Institutions Fund JW Marriott at L.A. Live 900 West Olympic Boulevard Los Angeles, CA 90015 213-765-8600 Conference Registration Diamond Ballroom Plaza To Conference Ballrooms Ź Studio 3 Atrium Platinum Ballroom Olympic Studios 1, 2 Gold Ballroom 2 elcome to the 2016 National Interagency Community Reinvestment Conference and [V3VZ(UNLSLZHJP[`[OH[L_LTWSPÄLZIV[O[OLJOHSSLUNLZHUKVWWVY[\UP[PLZMHJPUN[OL Wcommunity development sector. Economic opportunity does not happen in a vacuum: it takes a coordinated approach to housing, LK\JH[PVUW\ISPJZHML[`OLHS[OJHYL[YHUZWVY[H[PVUHUKQVIZ6]LY[OLUL_[[OYLLKH`Z^L^PSS L_WSVYL[OLWH[O^H`Z[VVWWVY[\UP[`[OH[JHUJYLH[L]PIYHU[ULPNOIVYOVVKZMVYHSS(TLYPJHUZ >OL[OLY`V\»YLHIHURLYKL]LSVWLYVYJVTT\UP[`SLHKLY^LOVWL`V\^PSS[HRLM\SSHK]HU[HNLVM [OLSLHYUPUNHUKUL[^VYRPUNVWWVY[\UP[PLZ[OPZJVUMLYLUJLVMMLYZ;OLCRA Compliance track features an interagency team of top examiners from around the country. Sessions in this track cover virtually L]LY`HZWLJ[VM[OL*9(L_HTPUH[PVUWYVJLZZMVYHSSPUZ[P[\[PVUZPaLZHUKPUJS\KLILZ[WYHJ[PJLZ[OH[ L]LU[OLTVZ[L_WLYPLUJLK*9(VMÄJLYZ^PSSÄUK\ZLM\S ;OLZLZZPVUZPU[OLCommunity Development Policy and Practice trackOPNOSPNO[PUUV]H[P]LÄUHUJPUN Z[Y\J[\YLZZ[YH[LNPLZHUKWHY[ULYZOPWTVKLSZHPTLKH[I\PSKPUNWH[O^H`Z[VLJVUVTPJVWWVY[\UP[` PUSV^LYPUJVTLJVTT\UP[PLZ-VY^L»]LHKKLKHZLYPLZVM^VYRZOVWZLZZPVUZKLZPNULK[VIL ZRPSSI\PSKPUNVWWVY[\UP[PLZMVYWHY[PJPWHU[Z -

Baker V. Carr in Context: 1946-1964

BAKER V. CARR IN CONTEXT: 1946-1964 Stephen Ansolabehere and Samuel Issacharoff1 Introduction Occasionally in all walks of life, law included, there are breakthroughs that have the quality of truth revealed. Not only do such ideas have overwhelming force, but they alter the world in which they operate. In the wake of such breakthroughs, it is difficult to imagine what existed before. Such is the American conception of constitutional democracy before and after the “Reapportionment Revolution” of the 1960s. Although legislative redistricting today is not without its riddle of problems, it is difficult to imagine so bizarre an apportionment scheme as the way legislative power was rationed out in Tennessee, the setting for Baker v. Carr. Tennessee apportioned power through, in Justice Clark’s words, “a crazy quilt without rational basis.”2 Indeed, forty years after Baker, with “one person, one vote” a fundamental principle of our democracy, it may be hard to imagine what all the constitutional fuss was about. Yet the decision in Baker, which had striking immediate impact, marked a profound transformation in American democracy. The man who presided over this transformation, Chief Justice Earl Warren, called Baker “the most important case of [his] tenure on the Court.”3 Perhaps the simplest way to understand the problem is to imagine the role of the legislator faced with the command to reapportion legislative districts after each decennial Census. Shifts in population mean that new areas of a state are likely to emerge as the dominant forces of a legislature. But what if the power to stem the tide were as simple as refusing to reapportion? It happened at the national level when Congress, realizing that the swelling tide of immigrant and industrial workers had moved power to the Northeast and the Midwest, simply refused to reapportion after the 1920 Census. -

Download Between the Lines 2017

the LINES Vanderbilt University, 2016–17 RESEARCH and from the LEARNING UNIVERSITY LIBRARIAN Places and Spaces International exhibit unites students, faculty and staff in celebrating mapping technology Dear colleagues and friends, ast spring, the Vanderbilt Heard Libraries hosted Places & Spaces: Mapping Science, It is my pleasure to share with you Between the Lines, a publication of an international exhibition the Jean and Alexander Heard Libraries. In words, numbers and images, celebrating the use of data we offer a glimpse into the many ways our libraries support and enhance Lvisualizations to make sense of large MAPPING SCIENCE teaching, learning and research at Vanderbilt. Between the Lines will data streams in groundbreaking ways. introduce you to the remarkable things happening in the libraries and The campuswide exhibit proved to be perhaps even challenge your perception of the roles of libraries and intellectually enriching and socially unifying, according to campus leaders. librarians. We are grateful to the many donors and friends who made “The Places & Spaces: Mapping Science much of this work possible. exhibit brought together students, faculty and staff to celebrate technological The past academic year has been one of change for Vanderbilt’s Heard advances in data visualization that Libraries with new faces, new library services, new spaces and new facilitate our understanding of the world I programs. It has also been a year of continuity as we build collections, around us,” says Cynthia J. Cyrus, vice make resources accessible and provide contemplative and collaborative provost for learning and residential affairs. “From the disciplines of science and Ptolemy’s Cosmo- spaces for research and study. -

Historic Context Statement City of Benicia February 2011 Benicia, CA

Historic Context Statement City of Benicia February 2011 Benicia, CA Prepared for City of Benicia Department of Public Works & Community Development Prepared by page & turnbull, inc. 1000 Sansome Street, Ste. 200, San Francisco CA 94111 415.362.5154 / www.page-turnbull.com Benicia Historic Context Statement FOREWORD “Benicia is a very pretty place; the situation is well chosen, the land gradually sloping back from the water, with ample space for the spread of the town. The anchorage is excellent, vessels of the largest size being able to tie so near shore as to land goods without lightering. The back country, including the Napa and Sonoma Valleys, is one of the finest agriculture districts in California. Notwithstanding these advantages, Benicia must always remain inferior in commercial advantages, both to San Francisco and Sacramento City.”1 So wrote Bayard Taylor in 1850, less than three years after Benicia’s founding, and another three years before the city would—at least briefly—serve as the capital of California. In the century that followed, Taylor’s assessment was echoed by many authors—that although Benicia had all the ingredients for a great metropolis, it was destined to remain in the shadow of others. Yet these assessments only tell a half truth. While Benicia never became the great commercial center envisioned by its founders, its role in Northern California history is nevertheless one that far outstrips the scale of its geography or the number of its citizens. Benicia gave rise to the first large industrial works in California, hosted the largest train ferries ever constructed, and housed the West Coast’s primary ordnance facility for over 100 years. -

NPR's 'Political Junkie' Coming to Central New York

NPR’s ‘Political Junkie’ Coming to Central New York Ken Rudin, NPR’s long-time political editor best the same name, Ken Rudin will help set the scene known for his astonishing ability to recall arcane for the 2012 election season. facts regarding all things political will be WRVO’s Rudin and a team of NPR reporters won the Alfred I. guest for a public appearance at Syracuse Stage duPont-Columbia University Silver Baton award for Thursday, May 31st. Grant Reeher, Professor in excellence in broadcast journalism for coverage of the Maxwell School at Syracuse University, campaign finance in 2002. Ken has analyzed Director of the Campbell Public Affairs every congressional race nationally since 1984. Institute and host of WRVO’s Campbell Conversations will join him on-stage as From 1983 through 1991, Ken was deputy host and will pose questions submitted political director and later off-air Capitol Hill in advance by WRVO listeners. Tickets reporter covering the House for ABC News. are available online at WRVO.org. He first joined NPR in 1991 and is reported to have more than 70,000 campaign buttons Known as ‘The Political Junkie’ for his and other political items he has been collecting appearances on the Wednesday edition for more than 50 years. of Talk of the Nation with Neal Conan, and for the NPR blog that he writes of NPR’s Ken Rudin When we announced back in January our first ever WRVO Discovery WRVO to Cruise Cruise with NPR “Eminence in Residence” Carl Kasell aboard as with Carl Kasell our host, we had no idea how popular it would become with WRVO listeners. -

General Services Administration

Barbara J. Coleman Oral History Interview – JFK#1, 01/19/1968 Administrative Information Creator: Barbara J. Coleman Interviewer: John F. Stewart Date of Interview: January 19, 1968 Place of Interview: Washington D.C. Length: 31 pages Biographical Note Coleman was a journalist, a White House press aide (1961-1962), a member of Robert Kennedy’s Senate staff, and presidential campaign aide (1968). In this interview she discusses Pierre Salinger’s press operations during the 1960 primaries and the presidential campaign, the Democratic National Convention, and Salinger’s relationship with the Kennedy administration, among other issues. Access Open. Usage Restrictions According to the deed of gift signed June 29, 1973, copyright of these materials has been assigned to the United States Government. Users of these materials are advised to determine the copyright status of any document from which they wish to publish. Copyright The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research.” If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excesses of “fair use,” that user may be liable for copyright infringement. This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order if, in its judgment, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law. -

Replace with Your Title

Advancing Vertical Flight: A Historical Perspective on AHS International and its Times M.E. Rhett Flater L. Kim Smith AHS Executive Director (1991-2011) AHS Deputy Director (1993-2011) M. E. Rhett Flater & Associates M.E. Rhett Flater & Associates Pine Knoll Shores, NC Pine Knoll Shores, NC ABSTRACT1 This paper describes AHS’s vital role in the development of the rotorcraft industry, with particular emphasis on events since 1990. It includes first-hand accounts of the formation of the Society, how it matured and evolved, and the particular influences that compelled change. It describes key events which occurred during various stages of the Society’s growth, including the formation of its technical committees, the evolution of the AHS Annual Forum and technical specialists’ meetings, and the creation and evolution of the Society’s publications. Featured prominently are accounts of AHS’s role in pursuing a combined government, industry and academia approach to rotorcraft science and technology. Also featured is the creation in 1965 of the Army-NASA Agreement for Joint Participation in Aeronautics Technology, the establishment of the U.S. Army Rotorcraft Centers of Excellence, the National Rotorcraft Technology Center (NRTC), the inauguration of the Congressional Rotorcraft Caucus and its support for the U.S. defense industrial base for rotorcraft, the battle for the survival of NASA aeronautics and critical NASA subsonic ground test facilities, and the launching of the International Helicopter Safety Team (IHST). First Annual AHS Banquet, October 7, 1944. 1Presented at the AHS 72nd Annual Forum, West Palm Beach, Florida, USA, May 17-19, 2016. Copyright © 2016 by the American Helicopter Society International, Inc. -

Malcolm Kilduff Oral History Interview – JFK#2, 03/15/1976 Administrative Information

Malcolm Kilduff Oral History Interview – JFK#2, 03/15/1976 Administrative Information Creator: Malcolm Kilduff Interviewer: Bill Hartigan Date of Interview: March 15, 1976 Place of Interview: Washington D.C. Length: 21 pages Biographical Note Malcolm Kilduff (1927-2003) was the Assistant Press Secretary from 1962 to 1965 and the Information Director of Hubert Humphrey for President. This interview focuses on John F. Kennedy’s [JFK] diplomatic trips to other countries and Kilduff’s first-hand account of JFK’s assassination, among other topics. Access Open Usage Restrictions According to the deed of gift signed March 1, 2000, copyright of these materials has been assigned to the United States Government. Users of these materials are advised to determine the copyright status of any document from which they wish to publish. Copyright The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research.” If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excesses of “fair use,” that user may be liable for copyright infringement. This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order if, in its judgment, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law. The copyright law extends its protection to unpublished works from the moment of creation in a tangible form. -

Listen! WRVD 90.3 - WRVH 89.3 - WRVJ 91.7 - WRVN 91.9 - WRVO 89.9 - CELEBRATING 43 YEARS

Listen! www.wrvo.org WRVD 90.3 - WRVH 89.3 - WRVJ 91.7 - WRVN 91.9 - WRVO 89.9 - CELEBRATING 43 YEARS NPR’s ‘Political Junkie’ Ken Rudin WRVO Earns Top AP Honors... Again WRVO’s Guest at Syracuse Stage NPR Political Analyst Sets the 2012 Political Scene WRVO Reporter Ryan Delaney and News Director Catherine Loper accept AP awards on behalf of WRVO Public Media For the second year in a row WRVO received the Steve Flanders Award from the New York State Associated WRVO General Manager Michael Ameigh introduces Ken Press Broadcasters Association. The award, presented Rudin and moderator Grant Reeher at Syracuse Stage at the annual awards banquet in Saratoga Springs in Ken Rudin’s voice is becoming more and more famil- June, recognizes the radio station in New York state that iar as NPR’s election year coverage rolls out. Dubbed received the most first place awards for news and feature ‘NPR’s Political Junkie,’ he has a knack for putting com- reporting in annual competition with other stations in plex political strategy in perspective. Ken recalls from its class. WRVO’s Ryan Delaney and News Director memory facts and figures about obscure congressional Catherine Loper accepted the awards. WRVO has election contests long since forgotten by everyone else. received numerous awards from AP, the Syracuse Press Rudin’s hilarious ‘Scuttlebutton’ puzzles, vertical displays Club, and the New York State Broadcasters Association. of old campaign buttons that, when deciphered, reveal familiar phrases - and some bad puns - had the audience WRVO Discovery howling with laughter. Cruise Sets Sail WRVO Campbell Coversations host Grant Reeher from New York served as moderator for the May 30 event. -

THE TAKING of AMERICA, 1-2-3 by Richard E

THE TAKING OF AMERICA, 1-2-3 by Richard E. Sprague Richard E. Sprague 1976 Limited First Edition 1976 Revised Second Edition 1979 Updated Third Edition 1985 About the Author 2 Publisher's Word 3 Introduction 4 1. The Overview and the 1976 Election 5 2. The Power Control Group 8 3. You Can Fool the People 10 4. How It All BeganÐThe U-2 and the Bay of Pigs 18 5. The Assassination of John Kennedy 22 6. The Assassinations of Robert Kennedy and Dr. Martin Luther King and Lyndon B. Johnson's Withdrawal in 1968 34 7. The Control of the KennedysÐThreats & Chappaquiddick 37 8. 1972ÐMuskie, Wallace and McGovern 41 9. Control of the MediaÐ1967 to 1976 44 10. Techniques and Weapons and 100 Dead Conspirators and Witnesses 72 11. The Pardon and the Tapes 77 12. The Second Line of Defense and Cover-Ups in 1975-1976 84 13. The 1976 Election and Conspiracy Fever 88 14. Congress and the People 90 15. The Select Committee on Assassinations, The Intelligence Community and The News Media 93 16. 1984 Here We ComeÐ 110 17. The Final Cover-Up: How The CIA Controlled The House Select Committee on Assassinations 122 Appendix 133 -2- About the Author Richard E. Sprague is a pioneer in the ®eld of electronic computers and a leading American authority on Electronic Funds Transfer Systems (EFTS). Receiving his BSEE degreee from Purdue University in 1942, his computing career began when he was employed as an engineer for the computer group at Northrup Aircraft. He co-founded the Computer Research Corporation of Hawthorne, California in 1950, and by 1953, serving as Vice President of Sales, the company had sold more computers than any competitor.