Sharon Creech

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Absolutely Normal Chaos

ABSOlutELY NORMAL CHAOS Setting the Scene Mary Lou Finney is less than excited about her assignment to keep a journal over the summer. But then cousin Carl Ray comes to stay with her family, and what starts out as the dull dog days of summer quickly turns into the wildest roller coaster ride of all time. How was Mary Lou supposed to know what would happen with Carl Ray and the ring? Or with her boy-crazy best friend, Beth Ann? Or with the permanently pink Alex Cheevey? Suddenly, a boring school project becomes a record of the most incredible, unbelievable summer of Mary Lou’s life. Before Reading Absolutely Normal Chaos begins with a letter from Mary Lou to her teacher, Mr. Birkway, begging him not to read her summer journals. Ask the class if they have ever kept a journal. Would they like their teacher reading it? Why or why not? Discussion Questions 1. Describe Mary Lou’s relationship with Alex Cheevey. What is 5. Near the end of the summer Mary Lou writes, “I don’t even their relationship like at the start of the novel? How does it recognize myself when I read back over these pages” (p. 228). change? Why? What do you imagine their relationship is like In what ways has Mary Lou changed over the course of the after the book ends? novel? Is she more mature? Why? Provide examples from the book. 2. When Mary Lou is lamenting the end of the school year, she writes, “Isn’t that just typical? You wait and wait and wait for 6. -

Summer Reading

DIRECTIONS: Pick THREE books from this list, read them this summer and fill out the attached “LOVE IT OR LOSE IT?” sheet. Tell me if you LOVE these books or if our library should “LOSE THEM.” Return the sheet to Mrs. Guzik (or email it to me at [email protected]) by 8/31. You will earn a prize and be entered into a drawing for a $10 Barnes & Noble Gift Card. You will get one additional entry in the gift card drawing for every EXTRA book you read (after the first three). Plus, you’ll get a bonus entry for every book you choose from this list that was published in 1999 or earlier (in bolded italics). For Middle Grade Students (Gr. 3-5) For Middle A Corner of the Universe by Ann Martin (2003 NH) Grade Students (Gr. 3-5) A Single Shard by Linda Sue Park (2002 NW) The School Story by Andrew Clements (2004 CYRM W) A Year Down Yonder by Richard Peck (2002 NW) Sheep by Valerie Hobbs (2009 CYRM W) Absolutely Almost by Lisa Graff (2015 ALA) Shiloh by Phyllis Reynolds Naylor (1992 NW) Because of Winn-Dixie by Kate DiCamillo (2001 NH, 2003 CYRM W) Sounder by William Armstrong (1970 NW) Breadcrumbs by Anne Ursu (2011MA) Spaceheadz by Jon Scieszka (2010 MA) Breaking Stalin’s Nose by Eugene Yelchin (2012 NH) Splendors and Glooms by Laura Schlitz (2013 NH) The Castle in the Attic by Elizabeth Winthrop (1989 CYRM W) Starry River of the Sky by Grace Lin (2010 MA) The Cat Who Went to Heaven by Elizabeth Coatsworth (1930 NW) Stonewords: A Ghost Story by Pam Conrad (1995 CYRM W) Christopher Mouse by William Wise (2007 CYRM W) Strawberry Girl by Lois Lenski (1946 NW) City of Ember by Jeanne DuPrau (2003 MA) Strider by Beverly Cleary (1995 CYRM N) Coraline by Neil Gaiman (2002 MA) The Summer of the Swans by Betsy Byars (1971 NW) The Crossover by Kwame Alexander (2015 NW) The Tale of Despereaux by Kate DiCamillo (2004 NW) Dear Mr. -

Love That Dog Free

FREE LOVE THAT DOG PDF Sharon Creech | 112 pages | 08 Apr 2008 | HarperCollins | 9780064409599 | English | New York, NY, United States Love That Dog Discussion Guide | Scholastic Copyright by New Directions Publishing Corp. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Copyrightby Henry Holt and Co. Copyrightby Valerie Worth. Publisher Henry Holt and Co. The Apple by S. Rigg, from Love That Dog. Printed here by permission of HarperCollins Publishers. Text copyright by Arnold Adoff. Used by permission of HarperCollins Publishers. Copyright by Walter Dean Myers. Harper Trophy is a registered trademark of HarperCollins Publishers. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Summary: A young student, who comes to love poetry through a personal understanding of what different famous poems mean to him, surprises himself by writing his own inspired poem. ISBN [1. I dont understand the poem about the red wheelbarrow and the white chickens and why so much depends upon them. If that is Love That Dog poem about the red wheelbarrow and the white chickens then any words can be a poem. Love That Dog just got to make short lines. Do you promise not to read it out loud? Do you promise not to put it on the board? Okay, here it is, but I dont like it. So much depends upon a blue car splattered with mud speeding down the road. What do you mean Why does Love That Dog much depend upon a blue car? You didnt say before that I had to tell why. -

The YA Novel in the Digital Age by Amy Bright a Thesis

The YA Novel in the Digital Age by Amy Bright A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Department of English and Film Studies University of Alberta © Amy Bright, 2016 Abstract Recent research by Neilsen reports that adult readers purchase 80% of all young adult novels sold, even though young adult literature is a category ostensibly targeted towards teenage readers (Gilmore). More than ever before, young adult (YA) literature is at the center of some of the most interesting literary conversations, as writers, readers, and publishers discuss its wide appeal in the twenty-first century. My dissertation joins this vibrant discussion by examining the ways in which YA literature has transformed to respond to changing social and technological contexts. Today, writing, reading, and marketing YA means engaging with technological advances, multiliteracies and multimodalities, and cultural and social perspectives. A critical examination of five YA texts – Markus Zusak’s The Book Thief, Libba Bray’s Beauty Queens, Daniel Handler’s Why We Broke Up, John Green’s The Fault in Our Stars, and Jaclyn Moriarty’s The Ghosts of Ashbury High – helps to shape understanding about the changes and the challenges facing this category of literature as it responds in a variety of ways to new contexts. In the first chapter, I explore the history of YA literature in order to trace the ways that this literary category has changed in response to new conditions to appeal to and serve a new generation of readers, readers with different experiences, concerns, and contexts over time. -

Literature Circle Guide to LOVE THAT DOG by Sharon Creech

Literature Circle Guide to LOVE THAT DOG by Sharon Creech Book Summary Jack doesn’t care much for poetry, writing it or reading it. With the prodding of his teacher, though, he begins to write poems of his own — about a mysterious blue car, about a lovable dog. Slowly, he realizes that his brain isn’t “empty” and that he can write poems. After meeting one of his favorite writers, Walter Dean Meyers, Jack writes a special poem about a painful experience in his life, the death of his dog. By the end of the book, Jack realizes that writing and reading poetry is not only pleasurable, but that writing can be a way of dealing with painful memories. Instead of trying to forget those difficult experiences, he can make something creative out of them. Author Information Known for writing with a classic voice and unique style, Sharon Creech is the best- selling author of the Newbery Medal winner Walk Two Moons, and the Newbery Honor Book The Wanderer. She is also the first American in history to be awarded the CILIP Carnegie Medal for Ruby Holler. Her other works include the novels Love That Dog, Bloomability, Abolutely Normal Chaos, Chasing Redbird, and Pleasing the Ghost, and two picture books: A Fine, Fine School and Fishing in the Air. These stories are often centered around life, love, and relationships -- especially family relationships. Growing up in a big family in Cleveland, Ohio, helped Ms. Creech learn to tell stories that wouldn't be forgotten in all of the commotion: "I learned to exaggerate and embellish, because if you didn't, your story was drowned out by someone else's more exciting one." Suggested Answers to Literature Circle Questions 1. -

Love-That-Dog-By-Sharon-Creech.Pdf

Love That Dog Recommended for Grades 4-8 Book Summary: Love That Dog Written as a series of journal entries, we meet a boy named Jack. Jack thinks poetry is for girls. With some encouragement from his teacher, he begins to write his own poems. As time passes, he goes from not wanting anyone to know he wrote the poems to offering advice on how to best format the poems for the class to read. [SPOILER] Influenced by one of his favorite writers, Walter Dean Meyers, Jack writes a special poem about the death of his dog. He becomes so passionate about poetry that he writes to Walter Dean Myers and convinces him to visit his school. In the end, Jack has discovered that he really enjoys reading and writing poetry. He uses poetry to express his feelings. Just as he was inspired my many famous poets, his poems now inspire his fellow classmates. At the end of the book, we can read all those poems which Jack referred to in his journal. Author Biography: Sharon Creech Sharon Creech was born on July 29, 1945 in South Euclid, Ohio. Her rowdy family consisted of Mom, Dad, one sister, and three brothers. (A fictional account of what it was like in her family can be found in her book Absolutely Normal Chaos. In the summertime, her family would take a vacation to Wisconsin or Michigan. Once they went to Idaho, which became the basis of her book Walk Two Moons. She received her Bachelor of Arts from Hiram College and a Master of Arts from George Mason University. -

Newbery Award Winners Newbery Award Winners

Waterford Public Library Newbery Award Winners Newbery Award Winners 1959: The Witch of Blackbird Pond by Elizabeth George Speare 1958: Rifles for Watie by Harold Keith Newbery Award Winners 1996: The Midwife's Apprentice by Karen Cushman 1957: Miracles on Maple Hill by Virginia Sorenson 1995: Walk Two Moons by Sharon Creech 1956: Carry On, Mr. Bowditch by Jean Lee Latham 1994: The Giver by Lois Lowry 1955: The Wheel on the School by Meindert DeJong The Newbery Medal was named for 18th-century British bookseller 1993: Missing May by Cynthia Rylant 1954: ...And Now Miguel by Joseph Krumgold John Newbery. It is awarded annually by the Association for 1992: Shiloh by Phyllis Reynolds Naylor 1953: Secret of the Andes by Ann Nolan Clark Library Service to Children, a division of the American Library 1991: Maniac Magee by Jerry Spinelli 1952: Ginger Pye by Eleanor Estes Association, to the author of the most distinguished contribution to 1990: Number the Stars by Lois Lowry 1951: Amos Fortune, Free Man by Elizabeth Yates American literature for children. 1989: Joyful Noise: Poems for Two Voices by Paul Fleischman 1950: The Door in the Wall by Marguerite de Angeli 1988: Lincoln: A Photobiography by Russell Freedman 1949: King of the Wind by Marguerite Henry 2021: When You Trap a Tiger by Tae Keller 1987: The Whipping Boy by Sid Fleischman 1948: The Twenty-One Balloons by William Pène du Bois 1986: Sarah, Plain and Tall by Patricia MacLachlan 1947: Miss Hickory by Carolyn Sherwin Bailey 2020: New Kid, written and illustrated by Jerry Craft 1985: The Hero and the Crown by Robin McKinley 1946: Strawberry Girl by Lois Lenski 2019: Merci Suárez Changes Gears by Meg Medina 1984: Dear Mr. -

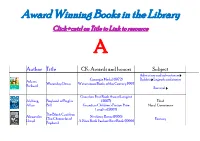

Award Winning Books in the Library Click+Cntrl on Title to Link to Resource A

Award Winning Books in the Library Click+cntrl on Title to Link to resource A Author Title CK: Awards and honors Subject Adventure and adventurers › Carnegie Medal (1972) Rabbits › Legends and stories Adams, Watership Down Waterstones Books of the Century 1997 Richard Survival › Guardian First Book Award Longlist Ahlberg, Boyhood of Buglar (2007) Thief Allan Bill Guardian Children's Fiction Prize Moral Conscience Longlist (2007) The Black Cauldron Alexander, Newbery Honor (1966) (The Chronicles of Fantasy Lloyd A Horn Book Fanfare Best Book (1966) Prydain) Author Title CK: Awards and honors Subject The Book of Three Alexander, A Horn Book Fanfare Best Book (1965) (The Chronicles of Fantasy Lloyd Prydain Book 1) A Horn Book Fanfare Best Book (1967) Alexander, Castle of Llyr Fantasy Lloyd Princesses › A Horn Book Fanfare Best Book (1968) Taran Wanderer (The Alexander, Fairy tales Chronicles of Lloyd Fantasy Prydain) Carnegie Medal Shortlist (2003) Whitbread (Children's Book, 2003) Boston Globe–Horn Book Award Almond, Cuban Missile Crisis, 1962 › The Fire-eaters (Fiction, 2004) David Great Britain › History Nestlé Smarties Book Prize (Gold Award, 9-11 years category, 2003) Whitbread Shortlist (Children's Book, Adventure and adventurers › Almond, 2000) Heaven Eyes Orphans › David Zilveren Zoen (2002) Runaway children › Carnegie Medal Shortlist (2000) Amateau, Chancey of the SIBA Book Award Nominee courage, Gigi Maury River Perseverance Author Title CK: Awards and honors Subject Angeli, Newbery Medal (1950) Great Britain › Fiction. › Edward III, Marguerite The Door in the Wall Lewis Carroll Shelf Award (1961) 1327-1377 De A Horn Book Fanfare Best Book (1950) Physically handicapped › Armstrong, Newbery Honor (2006) Whittington Cats › Alan Newbery Honor (1939) Humorous stories Atwater, Lewis Carroll Shelf Award (1958) Mr. -

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz Book Title Author Points No. Level 6201 EN 213 Valentines Cohen, Barbara 4.0 1.0 9001 EN 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins, The Seuss, Dr. 4.0 1.0 8501 EN Addie's Long Summer Lawlor, Laurie 4.0 5.0 302 EN All About Sam Lowry, Lois 4.0 3.0 903719 All About Wolves (HSP Edition) Goldish, Meish 4.0 0.5 EN 453 EN Almost Starring Skinnybones Park, Barbara 4.0 3.0 138780 Anaheim Ducks Kelley, K.C. 4.0 0.5 EN 5204 EN Angel's Mother's Baby Delton, Judy 4.0 3.0 903425 Apollo to the Moon (HSP Edition) Lynch, Patricia Ann 4.0 0.5 EN 14654 B. Bear Scouts and the Humongous Berenstain, Stan 4.0 1.0 EN Pumpkin, The 17552 B. Bear Scouts Save That Backscratcher, Berenstain, Stan 4.0 1.0 EN The 5503 EN B. Bears and Too Much Junk Food, The Berenstain, Stan/Jan 4.0 0.5 7498 EN B. Bears' Trouble with Money, The Berenstain, Stan 4.0 0.5 80238 Basset Hounds Stone, Lynn M. 4.0 0.5 EN 134643 Best of Figure Skating, The Allen, Kathy 4.0 0.5 EN 138781 Boston Bruins Kelley, K.C. 4.0 0.5 EN 72850 Brachiosaurus Matthews, Rupert 4.0 0.5 EN 108004 Bulldogs Stone, Lynn M. 4.0 0.5 EN 903483 Button Time (HSP Edition) O'Brien, Anne 4.0 0.5 EN 18711 Care and Feeding of Dragons, The Seabrooke, Brenda 4.0 3.0 EN 159 EN Case of the Elevator Duck, The Berends, Polly 4.0 1.0 660 EN Celery Stalks at Midnight, The Howe, James 4.0 2.0 5213 EN Certain Small Shepherd, A Caudill, Rebecca 4.0 1.0 5214 EN Championship Game Hughes, Dean 4.0 2.0 903722 Cheyenne Horses (HSP Edition) Livorse, Kay 4.0 0.5 EN 138782 Chicago Blackhawks Adelman, Beth 4.0 0.5 EN 903318 Chinese Silk Traders (HSP Edition), The Gallego, Isabel 4.0 0.5 EN Boyd, Candy 309 EN Circle of Gold 4.0 3.0 Dawson 52859 Clifford's Big Book of Things to Know Bridwell, Norman 4.0 0.5 EN 19559 Cock-a-doodle Dudley Peet, Bill 4.0 0.5 EN 903319 Crater (HSP Edition), The Falstein, Mark 4.0 0.5 EN 9604 EN Curse of the Mummy's Tomb, The Stine, R.L. -

What Is the Fall 2019 Educational Outreach Tour?

EDUCATIONAL OUTREACH TOUR - FALL 2019 EDUCATION PACK LOVE THAT DOG — THE THEATRE What is the Fall 2019 Educational Outreach Tour? Every fall, the Montana Repertory Theatre, a professional theatre company in residence at the University of Montana’s School of Theatre & Dance in Missoula, MT, tours a short play and accompanying workshop to Middle and High schools across Montana. The plays we choose or commission are educational in nature, inspired by the Montana State Middle and High School curriculum, and, although, our target audience is Montana students, ages 11-18 years of age, it is not unusual for us to also perform for community colleges, arts organizations and local libraries across the state of Montana as well. For More Information Please Contact: Teresa Waldorf / Educational Outreach Coordinator (406) 243-2854 / [email protected] www.montanarep.com SPECIAL THANKS to the New York City Children’s Theatre for the use of their original education packet materials and for creating this beautiful play. MONTANA REPERTORY THEATRE 2019-2020 SEASON Montana Repertory Theatre | montanarep.com | page 2 LOVE THAT DOG — THE SHOW What was up with the snowy Hints on Theatre Etiquette woods poem we read today? Dear Principals and Teachers, Why doesn’t a person just keep going if he has so many miles to go before he sleeps?” In Love Thank you for this opportunity to perform for That Dog, a one-person play adapted from your students. Our actors will give a curtain the book by Sharon Creech, a young student speech before the show. Because we want this ruminates on the confusing, pointless nature experience to be as pleasant as possible for of poetry and the complete impossibility of a you, your students, and the performers, we ask person writing their own poems. -

Walk Two Moons</Em> Literature Circle Questions

Literature Circle Questions Use these questions and the activities that follow to get more out of the experience of reading Walk Two Moons by Sharon Creech. 1. What does Sal say are the “real reasons” her grandparents are taking her to Idaho? 2. At the very end of the story, why does Sal say that she is jealous of Phoebe? 3. Why doesn’t Sal like her new home in Euclid, Ohio? How is it different from her former home in Kentucky? 4. Sal says that her story is hidden behind Phoebe’s. What do you think she means by this? 5. As Sal gets to know Phoebe and the Winterbottom family, she notices some odd things about their family. What does Sal notice, and why does she think that Mrs. Winterbottom is unhappy? 6. As you read, did any of the characters surprise you? Who turned out to be different than you first expected? 7. If you had a friend who was experiencing family problems like Sal and Phoebe, how would you try to help? What kind of advice would you give your friend? 8. In chapter 41, Sal remembers the time her dog Moody Blue had puppies. How does she compare Moody Blue’s behavior to her mother’s? What do we learn about Sal’s mother through this comparison? 9. Of her Gram and Gramps Hiddle, Sal says, “My grandparents can get into trouble as easily as a fly can land on a watermelon.” What are some examples of this from the story? 10. What do Phoebe’s and Sal’s mothers have in common? Compare the two mothers, including their personalities, their problems, and their relationships with their children. -

Literature Circle Questions

Literature Circle Questions Use these questions and activities that follow to get more out of the experience of reading Granny Torrelli Makes Soup by Sharon Creech. 1. List some of the things Rosie likes about Bailey. 2. Who is Pardo? How is he like Bailey? 3. What happened the first day Rosie had to go to school? Why does Bailey have to go to a different school? 4. Make a list of the non-English words and phrases that Granny Torrelli says and what they mean. If you see a word that’s not directly explained, guess its meaning from context. 5. When Rosie and Bailey put on the play about the father and mother, Bailey gets very upset. Why? What do the things he says playing father tell you about his real father? 6. Both Rosie and Granny Torrelli tell stories involving a dog. Compare their two stories. Why did each of them get involved with a dog? How are their experiences similar? Different? 7. How is Bailey and Rosie’s friendship different than one between two sighted people? Compare their friendship to one of your own. 8. After Bailey and Rosie stop fighting, Rosie thinks “something else is squeezing in between us.” What is it? Do you think Bailey feels it too? Why or why not? 9. Why does Rosie keep the fact that she’s learning Braille a secret? Why is Bailey mad at Rosie for learning Braille but happy to tutor Janine? 10. What makes Rosie become her "ice queen" self? Her "tiger" self? Her "sly fox" self? What emotions does she feel in each case? How does she behave? Do other characters have different selfs? 11.