Download Chapter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NEW RELEASE GUIDE September 3 September 10 ORDERS DUE JULY 30 ORDERS DUE AUGUST 6

ada–music.com @ada_music NEW RELEASE GUIDE September 3 September 10 ORDERS DUE JULY 30 ORDERS DUE AUGUST 6 2021 ISSUE 19 September 3 ORDERS DUE JULY 30 SENJUTSU LIMITED EDITION SUPER DELUXE BOX SET Release Date: September 3, 2021 INCLUDES n Standard 2CD Digipak with 28-page booklet n Blu-Ray Digipak • “The Writing On The Wall” • Making Of “The Writing On The Wall” • Special Notes from Bruce Dickinson • 20-page booklet n 3 Illustrated Art Cards n 3D Senjutsu Eddie Lenticular n Origami Sheet with accompanying instructions to produce an Origami version of Eddie’s Helmet, all presented in an artworked envelope n Movie-style Poster of “The Writing On The Wall” n All housed in Custom Box made of durable board coated with a gloss lamination TRACKLIST CD 1 1. Senjutsu (8:20) 2. Stratego (4:59) 3. The Writing On The Wall (6:23) 4. Lost In A Lost World (9:31) 5. Days Of Future Past (4:03) 6. The Time Machine (7:09) CD 2 7. Darkest Hour (7:20) 8. Death of The Celts (10:20) 9. The Parchment (12:39) 10. Hell On Earth (11:19) BLU-RAY • “The Writing On The Wall” Video • “The Writing On The Wall” The Making Of • Special notes from Bruce Dickinson LIMITED EDITION SUPER DELUXE BOX SET List Price: $125.98 | Release Date: 9/3/21 | Discount: 3% Discount (through 9/3/21) Packaging: Super Deluxe Box | UPC: 4050538698114 Returnable: YES | Box Lot: TBD | Units Per Set: TBD | File Under: Rock SENJUTSU Release Date: September 3, 2021 H IRON MAIDEN Take Inspiration From The East For Their 17th Studio Album, SENJUTSU H Brand new double album shows band maintain -

WHAT USE IS MUSIC in an OCEAN of SOUND? Towards an Object-Orientated Arts Practice

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Oxford Brookes University: RADAR WHAT USE IS MUSIC IN AN OCEAN OF SOUND? Towards an object-orientated arts practice AUSTIN SHERLAW-JOHNSON OXFORD BROOKES UNIVERSITY Submitted for PhD DECEMBER 2016 Contents Declaration 5 Abstract 7 Preface 9 1 Running South in as Straight a Line as Possible 12 2.1 Running is Better than Walking 18 2.2 What You See Is What You Get 22 3 Filling (and Emptying) Musical Spaces 28 4.1 On the Superficial Reading of Art Objects 36 4.2 Exhibiting Boxes 40 5 Making Sounds Happen is More Important than Careful Listening 48 6.1 Little or No Input 59 6.2 What Use is Art if it is No Different from Life? 63 7 A Short Ride in a Fast Machine 72 Conclusion 79 Chronological List of Selected Works 82 Bibliography 84 Picture Credits 91 Declaration I declare that the work contained in this thesis has not been submitted for any other award and that it is all my own work. Name: Austin Sherlaw-Johnson Signature: Date: 23/01/18 Abstract What Use is Music in an Ocean of Sound? is a reflective statement upon a body of artistic work created over approximately five years. This work, which I will refer to as "object- orientated", was specifically carried out to find out how I might fill artistic spaces with art objects that do not rely upon expanded notions of art or music nor upon explanations as to their meaning undertaken after the fact of the moment of encounter with them. -

David Toop Ricocheting As a 1960S Teenager Between Blues Guitarist

David Toop Ricocheting as a 1960s teenager between blues guitarist, art school dropout, Super 8 film loops and psychedelic light shows, David Toop has been developing a practice that crosses boundaries of sound, listening, music and materials since 1970. This practice encompasses improvised music performance (using hybrid assemblages of electric guitars, aerophones, bone conduction, lo-fi archival recordings, paper, sound masking, water, autonomous and vibrant objects), writing, electronic sound, field recording, exhibition curating, sound art installations and opera (Star-shaped Biscuit, performed in 2012). It includes seven acclaimed books, including Rap Attack (1984), Ocean of Sound (1995), Sinister Resonance (2010) and Into the Maelstrom (2016), the latter a Guardian music book of the year, shortlisted for the Penderyn Music Book Prize. Briefly a member of David Cunningham’s pop project The Flying Lizards (his guitar can be heard sampled on “Water” by The Roots), he has released thirteen solo albums, from New and Rediscovered Musical Instruments on Brian Eno’s Obscure label (1975) and Sound Body on David Sylvian’s Samadhisound label (2006) to Entities Inertias Faint Beings on Lawrence English’s ROOM40 (2016). His 1978 Amazonas recordings of Yanomami shamanism and ritual - released on Sub Rosa as Lost Shadows (2016) - were called by The Wire a “tsunami of weirdness” while Entities Inertias Faint Beings was described in Pitchfork as “an album about using sound to find one’s own bearings . again and again, understated wisps of melody, harmony, and rhythm surface briefly and disappear just as quickly, sending out ripples that supercharge every corner of this lovely, engrossing album.” In the early 1970s he performed with sound poet Bob Cobbing, butoh dancer Mitsutaka Ishii and drummer Paul Burwell, along with key figures in improvisation, including Derek Bailey, Evan Parker, Georgie Born, Hugh Davies, John Stevens, Lol Coxhill, Frank Perry and John Zorn. -

Still Lost Inside the Velvet Trail: March New Album Reviews Pt. 2

Still Lost Inside The Velvet Trail: March New Album Reviews Pt. 2. Music | Bittles‘ Magazine Have you heard the new Madonna record yet? Terrible! The entire time I was listening to it the only thing I could think was »That poor woman!«. Whoever advised her that songs like Bitch I’m Madonna were a good idea deserves to be locked in a room with Mark Ronson for an entire day. Luckily there is some fantastic new music out there which more than makes up for the inane racket created by the Peter Pan of pop. By JOHN BITTLES For example we have Vessels, Fort Romeau, Phildel, Mu-Ziq, SCNTST, Mike Simonetti and more bringing out albums which ably counteract all the shit you find in the charts. You might also notice that this week begins a brand new trend where I give each album a rating out of ten. The powers that be were against it, and have made numerous attempts on my life, but until I get bored of it, this new regime is here to stay. So, put on your cowboy hat, ensure your whiskers are well groomed, that the cat is fed, and let us begin… This week we’ll start with an album which has been rocking my stereo ever since it came into my life. Dilate by former math rockers Vessels sees the Leeds-based four piece move away from the post rock of their previous output and into the world of groove-some techno and late night electronica. This is so good one listen can give you an erection for a week (not clinically proven). -

– Agenge D'épopées Musicales –

– AGENGE D’ÉPOPÉES MUSICALES – L’AGENCE SUPER! est une agence artistique créée en 2006 par Julien Catala, à la fois défricheuse de talent, producteur de concerts et festivals, tourneur, programmateur d’événements, agitateur… Représentant aujourd’hui plus de 300 artistes internationaux entre têtes d’affiches confirmées (The XX, Nicolas Jaar, Bon Iver, Cigarettes After Sex, Polo & Pan…) et jeunes loups de l’avant garde musicale internationale (Alex Cameron, Shame, Bicep, Tom Misch … ), SUPER! est devenu en quelques années un véritable “label”, symbole de la musique live indépendante mondiale. PLUS DE SUPER! est aussi producteur du Pitchfork Music Festival Paris 16 000 LIKES qui se déroule depuis 2011 à la Grande Halle de la Villette, coproducteur du Festival Cabourg Mon Amour en juin sur la côte normande et coproducteur de Biarritz En Eté! dont la première édition aura lieu en juillet 2018. PLUS DE 11 000 FOLLOWERS Au fil des années, SUPER! a également développé une activité de production évènementielle en travaillant avec des marques et médias comme Red Bull, Converse, Chanel, Society et de direction artistique avec le festival Villette Sonique, les Inrocks ou encore la Fondation Louis Vuitton. Enfin, SUPER! PLUS DE dirige la salle de concert Le Trabendo, lieu parisien des 3 000 FOLLOWERS musiques actuelles et émergentes, situé dans le Parc de la Villette. Défricheur des nouvelles tendances musicales : rock, folk, pop et électronique, SUPER! incarne un projet WWW.SUPERMONAMOUR.COM artistique fort, radar de l’innovation musicale internationale. -

2.+ENG Dossierprensa2018.Pdf

1 THE FESTIVAL 3 LINEUP 5 PLACES 11 ORGANIZATION AND PARTNERS 12 TICKETS 14 GRAPHIC CAMPAIGN 15 PRESS QUOTES 16 CONTACT 17 2 THE FESTIVAL Primavera Sound has always concentrated all its efforts on uniting the latest musical proposals from the independent scene together with already well established artists, while embracing any style or genre in the line up, fundamentally looking for quality and essentially backing pop and rock as well as underground electronic and dance music. Over the last years, the festival has had the most diverse range of artists. Some of those who have been on stage are Radiohead, Pixies, Arcade Fire, PJ Harvey, The National, Nine Inch Nails, Kendrick Lamar, Neil Young, Sonic Youth, Portishead, Pet Shop Boys, Pavement, Echo & The Bunnymen, Lou Reed, My Bloody Valentine, Brian Wilson, Pulp, Patti Smith, Nick Cave, Cat Power, Public Enemy, Franz Ferdinand, Television, Devo, Enrique Morente, The White Stripes, LCD Soundsystem, Tindersticks, Queens of the Stone Age, She- llac, Dinosaur Jr., New Order, Fuck Buttons, Swans, The Cure, Bon Iver, The xx, Iggy & The Stooges, De La Soul, Marianne Faithfull, Blur, Wu-Tang Clan, Phoenix, The Jesus and Mary Chain, Tame Impala, The Strokes, Belle & Sebastian, Antony & the Johnsons, The Black Keys, James Blake, Interpol and Sleater-Kinney amongst many others. Primavera Sound has consolidated itself as the urban festival par excellence with unique characteristics that have projected it internationally as a reference cultural event. The event stands out from other large music events and is faithful to its original artistic idea, keeping the same standards and maintaining the same qua- lity of organization of past years, without resorting to more commercial bands. -

2017 MAJOR EURO Music Festival CALENDAR Sziget Festival / MTI Via AP Balazs Mohai

2017 MAJOR EURO Music Festival CALENDAR Sziget Festival / MTI via AP Balazs Mohai Sziget Festival March 26-April 2 Horizon Festival Arinsal, Andorra Web www.horizonfestival.net Artists Floating Points, Motor City Drum Ensemble, Ben UFO, Oneman, Kink, Mala, AJ Tracey, Midland, Craig Charles, Romare, Mumdance, Yussef Kamaal, OM Unit, Riot Jazz, Icicle, Jasper James, Josey Rebelle, Dan Shake, Avalon Emerson, Rockwell, Channel One, Hybrid Minds, Jam Baxter, Technimatic, Cooly G, Courtesy, Eva Lazarus, Marc Pinol, DJ Fra, Guim Lebowski, Scott Garcia, OR:LA, EL-B, Moony, Wayward, Nick Nikolov, Jamie Rodigan, Bahia Haze, Emerald, Sammy B-Side, Etch, Visionobi, Kristy Harper, Joe Raygun, Itoa, Paul Roca, Sekev, Egres, Ghostchant, Boyson, Hampton, Jess Farley, G-Ha, Pixel82, Night Swimmers, Forbes, Charline, Scar Duggy, Mold Me With Joy, Eric Small, Christer Anderson, Carina Helen, Exswitch, Seamus, Bulu, Ikarus, Rodri Pan, Frnch, DB, Bigman Japan, Crawford, Dephex, 1Thirty, Denzel, Sticky Bandit, Kinno, Tenbagg, My Mate From College, Mr Miyagi, SLB Solden, Austria June 9-July 10 DJ Snare, Ambiont, DLR, Doc Scott, Bailey, Doree, Shifty, Dorian, Skore, March 27-April 2 Web www.electric-mountain-festival.com Jazz Fest Vienna Dossa & Locuzzed, Eksman, Emperor, Artists Nervo, Quintino, Michael Feiner, Full Metal Mountain EMX, Elize, Ernestor, Wastenoize, Etherwood, Askery, Rudy & Shany, AfroJack, Bassjackers, Vienna, Austria Hemagor, Austria F4TR4XX, Rapture,Fava, Fred V & Grafix, Ostblockschlampen, Rafitez Web www.jazzfest.wien Frederic Robinson, -

The Aesthetics of Acid

The Aesthetics Of Acid by Rick Bull Since the technological paranoia of the cold-war era, and the ensuing political and social consequences of the military technological boom, the development of electronic musics and proliferation of technologies through the 1970’s to the 90’s has seen the amalgamation of a multitude of cultural music ‘systems’- the formation of a universal and hybridised(ing) ‘pop aesthetic’1. In the West at least, the employment of electronic music technology has largely been used to reinforce the ‘classificatory arrangements’2 of the anglo-saxon listening ear - those classical tonal / structural orders criticised by the likes of Webern, Schoenberg and Boulez3......Towards the end of the 1980’s however, the popular appropriation of available technologies was challenged greatly by groups of experimentalists from Detroit, Chicago and Frankfurt - leaders of the ‘acid house’ explosion of the late 80’s, whose musics’ roots greatly shaped the aesthetic of today’s diversified ‘techno’ music genre. Much could be discussed in regards to history and subsequent sterilisation / diversification of such music, yet this essay seeks to focus primarily upon the change in cultural ‘hearing’ that could be suggested has occurred in the late 20th century; reflected and catalysed by the appropriators of frequently ‘obsolete’ musical technologies. I suggest, that through the popularised use of sampling and analogue tone production, and overall shift in the electro- pop listening aesthetic can be observed; ie. that from high to frequently ‘low’ tone fidelity - from a transparent to ‘opaque’ technological ethic, from a melodic / harmonic to largely modal and heavily rhythm based ideal. -

The Smooth Space of Field Recording

1 The Smooth Space of Field Recording Four Projects Sonicinteractions, Doublerecordings, “Dense Boogie” and ‘For the Birds’ Ruth Hawkins Goldsmiths, University of London PhD MUSIC (Sonic Arts) 2013 2 The work presented in the thesis is my own, except where otherwise stated 3 Acknowledgments Many thanks to Dr John Levack Drever, who supervised this thesis, and to the following individuals and organizations who gave me permission to record their work; provided information, technical and other support; and gave me opportunities to publish or screen parts of the work presented here. Sebastian Lexer. Natasha Anderson; Sean Baxter; David Brown; Rob Lambert; John Lely; Anthony Pateras; Eddie Prevost; Seymour Wright. Oliver Bown; Lawrence Casserley; Li Chuan Chong; Thomas Gardner; Chris Halliwell; Dominic Murcott; Aki Pasoulas; Lukas Pearce; Alejandro Viñao; Simon Zagourski-Thomas. Anya Bickerstaff. Lucia H. Chung. Dr Peter Batchelor; Marcus Boon; Mike Brown; Brian Duguid; Prof Elisabeth Le Guin; Dr Luciana Parisi; Prof Keith Potter; Dr Dylan Robinson; Geoff Sample. Rick Campion; Emmanuel Spinelli; Ian Stonehouse. David Nicholson; Francis Nicholson. Dr Cathy Lane; Dr Angus Carlyle - CRiSAP; Prof Leigh Landy; Dr Katharine Norman - Organised Sound; Helen Frosi - SoundFjord; EMS; Unit for Sound Practice Research - Goldsmiths, University of London. 4 Abstract This practice/theory PhD focuses on four projects that evolved from a wider objects, each of the projects was concerned with the ways in which ‘straight’ recording and real-world environments. The dissertation and projects attempt to reconcile, what has been depicted within the acoustic ecology movement as, the detrimental effects of ‘millions’ of recording productions and playbacks on individuals and global environments, by exploring alternative conceptions of environmental recorded sound. -

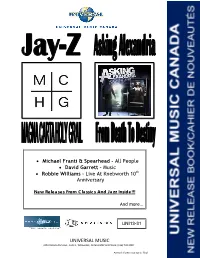

UNIVERSAL MUSIC • Michael Franti & Spearhead – All People • David

Michael Franti & Spearhead – All People David Garrett – Music Robbie Williams – Live At Knebworth 10th Anniversary New Releases From Classics And Jazz Inside!!! And more… UNI13-31 “Our assets on-line” UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2450 Victoria Park Ave., Suite 1, Willowdale, Ontario M2J 5H3 Phone: (416) 718.4000 Artwork shown may not be final UNIVERSAL MUSIC CANADA NEW RELEASE Artist/Title: JAY‐Z / MAGNA CARTA HOLY GRAIL (Standard Version) Bar Code: Cat. #: DEFW4027102 Price Code: SP Order Due: ASAP Release Date: July 9, 2013 8 57018 00418 2 File: Rap / Hip Hop Genre Code: 34 Box Lot: 25 Key Tracks: *SHORT SELL CYCLE “Holy Grail” ft. Justin Timberlake *NOT ACTUAL COVER Artist/Title: JAY‐Z / MAGNA CARTA HOLY GRAIL (Deluxe Version) Bar Code: Cat. #: B001887702 Price Code: SPS Order Due: July 4, 2013 Release Date: July 23, 2013 8 57018 00414 4 File: Rap / Hip Hop Genre Code: 34 Box Lot: 25 Key Tracks: *SHORT SELL CYCLE “Holy Grail” ft. Justin Timberlake *NOT ACTUAL COVER KEY POINTS: • Over 50 Million Albums sold worldwide – 1 million in Canada! • 10 Grammy Awards including 3 for his 2009 release “Blueprint 3” which debuted #1 in Canada • Previous album Watch The Throne with Kanye West has scanned over 130,000 units • Magna Carta Holy Grail includes 15 brand new songs! • Deluxe Version includes intricate 6‐panel soft pack, 28‐page booklet with black o‐card. The idea behind the package is that it needs to be destroyed in order for the information inside to be revealed. • Massive advertising & promotional campaigns running from release throughout the -

March 10, 2021 Jordan Rakei Announces Late Night Tales Compilation, out April

March 10, 2021 For Immediate Release Jordan Rakei Announces Late Night Tales Compilation, Out April 9th Listen to Rakei’s Exclusive Cover of Jeff Buckley’s “Lover, You Should've Come Over” (Photo Credit: Dan Medhurst) The artist-curated mix series, Late Night Tales, is pleased to announce its next compilation, this time curated by multi-instrumentalist, vocalist and producer Jordan Rakei, out April 9th. For Rakei’s Late Night Tales, the first mix of the acclaimed series’ 20th year, the 28-year-old modern soul icon effortlessly stamps his own jazz and hip-hop driven sound all over this gorgeous array of handpicked tracks. A beautifully layered blend that is mirrored in the music he’s made, it comes as no surprise that such a supremely gifted songwriter should deliver a mix that is all about the song. “I wanted to try and showcase as many people as I knew on this mix,” says Rakei. “My idea of Late Night Tales was to distil a series of relaxing moments; the whole conceptual sonic of relaxation. So, I was trying to think of all the collaborators and friends that I knew, who’d recorded stuff with this horizontal vibe. Plus, I was also trying to help my friends' stuff get into the world. I know the story of Khruangbin blowing up after appearing on the series (in fact, I think that's how I discovered them). So, the main idea was to create a certain atmosphere, but also to help some of my favourite collaborators and buddies to give their songs a little push out into the world. -

SRH and HIV LINKAGES COMPENDIUM Indicators & Related Assessment Tools 2

SRH AND HIV LINKAGES COMPENDIUM Indicators & Related Assessment Tools 2 SRH AND HIV LINKAGES COMPENDIUM Indicators & Related Assessment Tools A product of the Inter-agency Working Group on SRH and HIV Linkages* Acknowledgements Thank you to everyone who participated in • Ministry of Health, Macedonia: Brankica the development of the Compendium of Mladenovik Gender Equality and HIV Indicators. This • Ministry of Health, Swaziland: includes representatives of government Nompumelelo Dlamini Mthunzi institutions, civil society organisations, • Population Council: Charlotte Warren the UN family, bilateral and multilateral agencies, international NGOs, and other • UNAIDS: Tobias Alfven, James Guwani, partners who contributed in various ways Andiswa Hani, throughout the process. • UNFPA: Lynn Collins Special thanks go to members of the • WHO: Manjulaa Narasimhan and Lori Steering Group for their insights and Newman guidance through the process: We would like to particularly acknowledge • DfID: Anna Seymour Lynn Collins, Jon Hopkins, Kevin Osborne • FHI360: Francis Okello and Manjula Narasimhan for conceptualising • Global Fund to fight AIDS, TB and Malaria: and leading the process. We would also Motoko Seko like to thank to Roger Drew, David Hales and Kathy Attawell for their technical and • GNP+: Thembi Nkambule research support and guidance throughout • ICAP-Colombia University: Fatima Tsiouris the process. • International Community of Women Living We are grateful to Asa Andersson, James with HIV: Sonia Haerizadeh Guwani, Raymond Yekeye and