Aguna Speakers in Benin a Sociolinguistic Survey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics &A

Online Appendix for Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue (2014) Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics & Change Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue The following document lists the languages of the world and their as- signment to the macro-areas described in the main body of the paper as well as the WALS macro-area for languages featured in the WALS 2005 edi- tion. 7160 languages are included, which represent all languages for which we had coordinates available1. Every language is given with its ISO-639-3 code (if it has one) for proper identification. The mapping between WALS languages and ISO-codes was done by using the mapping downloadable from the 2011 online WALS edition2 (because a number of errors in the mapping were corrected for the 2011 edition). 38 WALS languages are not given an ISO-code in the 2011 mapping, 36 of these have been assigned their appropri- ate iso-code based on the sources the WALS lists for the respective language. This was not possible for Tasmanian (WALS-code: tsm) because the WALS mixes data from very different Tasmanian languages and for Kualan (WALS- code: kua) because no source is given. 17 WALS-languages were assigned ISO-codes which have subsequently been retired { these have been assigned their appropriate updated ISO-code. In many cases, a WALS-language is mapped to several ISO-codes. As this has no bearing for the assignment to macro-areas, multiple mappings have been retained. 1There are another couple of hundred languages which are attested but for which our database currently lacks coordinates. -

Monographie Ketou

REPUBLIQUE DU BENIN =-=-=-=-=-=-=-==-=-=-= MINISTERE DE LA PROSPECTIVE, DU DEVELOPPEMENT ET DE L’EVALUATION DE L’ACTION PUBLIQUE (MPDEAP) -=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-= INSTITUT NATIONAL DE LA STATISTIQUE ET DE L’ANALYSE ECONOMIQUE (INSAE) -=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-= MONOGRAPHIE DE LA COMMUNE DE KETOU DIRECTION DES ETUDES DEMOGRAPHIQUES Décembre 2008 TABLE DES MATIERES LISTE DES TABLEAUX ............................................................................................................ vi LISTE DES GRAPHIQUES ........................................................................................................ x PREFACE ..................................................................................................................................... xi NOTE METHODOLOGIQUE SUR LE RGPH-3 .................................................................. xiii SITUATION GEOGRAPHIQUE DE KETOU DANS LE BENIN .......................................... 1 SITUATION GEOGRAPHIQUE DE LA COMMUNE DE KETOU DANS LE DEPARTEMENT DU PLATEAU ............................................................................................... 2 1- GENERALITES ........................................................................................................................ 3 1-1 Présentation de la commune .................................................................................................. 3 1-1-1 Le relief .......................................................................................................................... -

The House of Oduduwa: an Archaeological Study of Economy and Kingship in the Savè Hills of West Africa

The House of Oduduwa: An Archaeological Study of Economy and Kingship in the Savè Hills of West Africa by Andrew W. Gurstelle A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology) in the University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee: Professor Carla M. Sinopoli, Chair Professor Joyce Marcus Professor Raymond A. Silverman Professor Henry T. Wright © Andrew W. Gurstelle 2015 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I must first and foremost acknowledge the people of the Savè hills that contributed their time, knowledge, and energies. Completing this dissertation would not have been possible without their support. In particular, I wish to thank Ọba Adétùtú Onishabe, Oyedekpo II Ọla- Amùṣù, and the many balè,̣ balé, and balọdè ̣that welcomed us to their communities and facilitated our research. I also thank the many land owners that allowed us access to archaeological sites, and the farmers, herders, hunters, fishers, traders, and historians that spoke with us and answered our questions about the Savè hills landscape and the past. This dissertion was truly an effort of the entire community. It is difficult to express the depth of my gratitude for my Béninese collaborators. Simon Agani was with me every step of the way. His passion for Shabe history inspired me, and I am happy to have provided the research support for him to finish his research. Nestor Labiyi provided support during crucial periods of excavation. As with Simon, I am very happy that our research interests complemented and reinforced one another’s. Working with Travis Williams provided a fresh perspective on field methods and strategies when it was needed most. -

Caractéristiques Générales De La Population

République du Bénin ~~~~~ Ministère Chargé du Plan, de La Prospective et du développement ~~~~~~ Institut National de la Statistique et de l’Analyse Economique Résultats définitifs Caractéristiques Générales de la Population DDC COOPERATION SUISSE AU BENIN Direction des Etudes démographiques Cotonou, Octobre 2003 1 LISTE DES TABLEAUX Tableau 1: Population recensée au Bénin selon le sexe, les départements, les communes et les arrondissements............................................................................................................ 3 Tableau G02A&B : Population Résidente recensée dans la commune de KANDI selon le sexe et par année d’âge ......................................................................... 25 Tableau G02A&B : Population Résidente recensée dans la commune de NATITINGOU selon le sexe et par année d’âge......................................................................................... 28 Tableau G02A&B : Population Résidente recensée dans la commune de OUIDAH selon le sexe et par année d’âge............................................................................................................ 31 Tableau G02A&B :Population Résidente recensée dans la commune de PARAKOU selon le sexe et par année d’âge (Commune à statut particulier).................................................... 35 Tableau G02A&B : Population Résidente recensée dans la commune de DJOUGOU selon le sexe et par année d’âge .................................................................................................... 40 Tableau -

Monographie Des Départements Du Zou Et Des Collines

Spatialisation des cibles prioritaires des ODD au Bénin : Monographie des départements du Zou et des Collines Note synthèse sur l’actualisation du diagnostic et la priorisation des cibles des communes du département de Zou Collines Une initiative de : Direction Générale de la Coordination et du Suivi des Objectifs de Développement Durable (DGCS-ODD) Avec l’appui financier de : Programme d’appui à la Décentralisation et Projet d’Appui aux Stratégies de Développement au Développement Communal (PDDC / GIZ) (PASD / PNUD) Fonds des Nations unies pour l'enfance Fonds des Nations unies pour la population (UNICEF) (UNFPA) Et l’appui technique du Cabinet Cosinus Conseils Tables des matières 1.1. BREF APERÇU SUR LE DEPARTEMENT ....................................................................................................... 6 1.1.1. INFORMATIONS SUR LES DEPARTEMENTS ZOU-COLLINES ...................................................................................... 6 1.1.1.1. Aperçu du département du Zou .......................................................................................................... 6 3.1.1. GRAPHIQUE 1: CARTE DU DEPARTEMENT DU ZOU ............................................................................................... 7 1.1.1.2. Aperçu du département des Collines .................................................................................................. 8 3.1.2. GRAPHIQUE 2: CARTE DU DEPARTEMENT DES COLLINES .................................................................................... 10 1.1.2. -

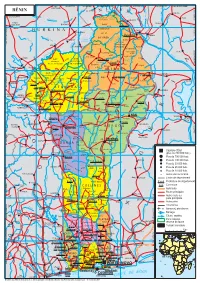

BENIN-2 Cle0aea97-1.Pdf

1° vers vers BOTOU 2° vers NIAMEY vers BIRNIN-GAOURÉ vers DOSSO v. DIOUNDIOU vers SOKOTO vers BIRNIN KEBBI KANTCHARI D 4° G vers SOKOTO vers GUSAU vers KONTAGORA I E a BÉNIN N l LA TAPOA N R l Pékinga I o G l KALGO ER M Rapides a vers BOGANDÉ o Gorges de de u JE r GA Ta Barou i poa la Mékrou KOULOU Kompa FADA- BUNZA NGOURMA DIAPAGA PARC 276 Karimama 12° 12° NATIONAL S o B U R K I N A GAYA k o TANSARGA t U DU W o O R Malanville KAMBA K Ka I bin S D É DU NIGER o ul o M k R G in u a O Garou g bo LOGOBOU Chutes p Guéné o do K IB u u de Koudou L 161 go A ZONE vers OUAGADOUGOU a ti r Kandéro CYNÉGÉTIQUE ARLI u o KOMBONGOU DE DJONA Kassa K Goungoun S o t Donou Béni a KOKO RI Founougo 309 JA a N D 324 r IG N a E E Kérémou Angaradébou W R P u Sein PAMA o PARC 423 ZONE r Cascades k Banikoara NATIONAL CYNÉGÉTIQUE é de Sosso A A M Rapides Kandi DE LA PENDJARI DE L'ATAKORA Saa R Goumon Lougou O Donwari u O 304 KOMPIENGA a Porga l é M K i r A L I B O R I 11° a a ti A j 11° g abi d Gbéssé o ZONE Y T n Firou Borodarou 124 u Batia e Boukoubrou ouli A P B KONKWESSO CYNÉGÉTIQUE ' Ségbana L Gogounou MANDOURI DE LA Kérou Bagou Dassari Tanougou Nassoukou Sokotindji PENDJARI è Gouandé Cascades Brignamaro Libant ROFIA Tiélé Ede Tanougou I NAKI-EST Kédékou Sori Matéri D 513 ri Sota bo li vers DAPAONG R Monrou Tanguiéta A T A K O A A é E Guilmaro n O Toukountouna i KARENGI TI s Basso N è s u Gbéroubou Gnémasson a Î o u è è è É S k r T SANSANN - g Kouarfa o Gawézi GANDO Kobli A a r Gamia MANGO Datori m Kouandé é Dounkassa BABANA NAMONI H u u Manta o o Guéssébani -

A Sociolinguistic Survey of the Gbe Language Communities of Benin and Togo Volume 10 Gbesi Language Area

DigitalResources Electronic Survey Report 2011-022 ® A sociolinguistic survey of the Gbe language communities of Benin and Togo Volume 10 Gbesi language area Gabi Schoch A sociolinguistic survey of the Gbe language communities of Benin and Togo Volume 10 Gbesi language area Gabi Schoch SIL International® 2011 SIL Electronic Survey Report 2011-022, March 2011 Copyright © 2011 Gabi Schoch and SIL International® All rights reserved A SOCIOLINGUISTIC SURVEY OF THE GBE LANGUAGE COMMUNITIES OF BENIN AND TOGO Series editor: Angela Kluge Gbe language family overview (by Angela Kluge) Volume 1: Kpési language area (by Evelin I. K. Durieux-Boon, Jude A. Durieux, Deborah H. Hatfield, and Bonnie J. Henson) Volume 2: Ayizo language area (by Deborah H. Hatfield and Michael M. McHenry) Volume 3: Kotafon language area (by Deborah H. Hatfield, Bonnie J. Henson, and Michael M. McHenry) Volume 4: Xwela language area (by Bonnie J. Henson, Eric C. Johnson, Angela Kluge) Volume 5: Xwla language area (by Bonnie J. Henson and Angela Kluge) Volume 6: Ci language area (by Bonnie J. Henson) Volume 7: Defi language area (by Eric C. Johnson) Volume 8: Saxwe, Daxe and Se language area (by Eric C. Johnson) Volume 9: Tofin language area (by Gabi Schoch) Volume 10: Gbesi language area (by Gabi Schoch) ii Contents Abstract 1. Introduction 2. Background 2.1. Language name and classification 2.2. Language area 2.3. Population 2.4. History of migration 2.5. Presence of other ethnic groups 2.6. Regional language use 2.7. Non-formal education 2.8. Religious situation 3. Previous linguistic research 4. -

Nigeria Benin Togo Burkina Faso Niger Ghana

! 1°E 2°E 3°E 4°E 5°E 6°E! ! ! ! MA-024 !Boulgou !Kantchari Gwadu Birnin-Kebbi ! Tambawel Matiacoali ! ! Pekinga Aliero ! ! ! A f r i c a Jega Niger ! Gunmi ! Anka Diapaga Koulou Birnin Tudu B! enin ! Karimam!a Bunza ! ! ! N N ° ° 2 Zugu 2 1 ! 1 Gaya Kamba ! Karimama Malanville ! ! Atlantic Burkina Faso Guéné ! Ocean Kombongou ! Dakingari Fokku ! Malanville ! ! Aljenaari ! Arli Mahuta ! ! Founougo ! Zuru Angaradébou ! ! Wasagu Kérémou Koko ! ! Banikoara ! Bagudo Banikoara ! ! ! Kaoje ! Duku Kandi ! Kandi ! Batia Rijau ! ! Porga N ! N ° Tanguieta ° 1 1 1 Ségbana 1 Kerou ! Yelwa Mandouri Segbana ! ! Konkwesso Ukata ! ! Kérou Gogounou Gouandé ! ! Bin-Yauri ! Materi ! ! Agwarra Materi Gogounou ! Kouté Tanguieta ! ! Anaba Gbéroubouè ! ! Ibeto Udara Toukountouna ! ! Cobly !Toukountouna Babana Kouande ! Kontagora Sinendé Kainji Reservoir ! ! Dounkassa Natitingou Kouandé ! Kalale ! ! Kalalé ! ! Bouka Bembereke ! Boukoumbe Natitingou Pehunko Sinende ! Kagara Bembèrèkè Auna ! ! Boukoumbé ! Tegina ! N N ° ° 0 Kandé 0 ! Birni ! 1 ! 1 ! Wawa Ndali Nikki ! ! New Bussa ! Kopargo Zungeru !Kopargo ! Kizhi Niamtougou Ndali ! Pizhi ! Djougou Yashikera ! ! Ouaké ! ! Pagoud!a Pya ! Eban ! Djougou Kaiama ! Guinagourou Kosubosu ! Kara ! ! ! Ouake Benin Perere Kutiwengi ! Kabou ! Bafilo Alédjo Parakou ! ! ! Okuta Parakou ! Mokwa Bassar ! Kudu ! ! Pénessoulou Jebba Reservoir ! Bétérou Kutigi ! ! ! Tchaourou Bida Kishi ! ! ! Tchamba ! Dassa ! Bassila Sinou 2°E ! ! Nigeria ! N N Sokodé ° ° ! Save 9 9 Bassila Savalou Bode-Sadu !Paouignan Tchaourou Ilesha Ibariba -

The Acoustic Correlates of Atr Harmony in Seven- and Nine

THE ACOUSTIC CORRELATES OF ATR HARMONY IN SEVEN- AND NINE- VOWEL AFRICAN LANGUAGES: A PHONETIC INQUIRY INTO PHONOLOGICAL STRUCTURE by COLEEN GRACE ANDERSON STARWALT Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Arlington in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT ARLINGTON May 2008 Copyright © by Coleen G. A. Starwalt 2008 All Rights Reserved DEDICATION To Dad who told me I could become whatever I set my mind to (May 6, 1927 – April 17, 2008) ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Where does one begin to acknowledge those who have walked alongside one on a long and often lonely journey to the completion of a dissertation? My journey begins more than ten years ago while at a “paper writing” workshop in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. I was consulting with Rod Casali on a paper about Ikposo [ATR] harmony when I casually mentioned my desire to do an advanced degree in missiology. Rod in his calm and gentle way asked, “Have you ever considered a Ph.D. in linguistics?” I was stunned, but quickly recoverd with a quip: “Linguistics!? That’s for smart people!” Rod reassured me that I had what it takes to be a linguist. And so I am grateful for those, like Rod, who have seen in me things that I could not see for myself and helped to draw them out. Then the One Who Directs My Steps led me back to the University of Texas at Arlington where I found in David Silva a reflection of the adage “deep calls to deep.” For David, more than anyone else during my time at UTA, has drawn out the deep things and helped me to give them shape and meaning. -

LCSH Section E

E (The Japanese word) E. J. Pugh (Fictitious character) E-waste [PL669.E] USE Pugh, E. J. (Fictitious character) USE Electronic waste BT Japanese language—Etymology E.J. Thomas Performing Arts Hall (Akron, Ohio) e World (Online service) e (The number) UF Edwin J. Thomas Performing Arts Hall (Akron, USE eWorld (Online service) UF Napier number Ohio) E. Y. Mullins Lectures on Preaching Number, Napier BT Centers for the performing arts—Ohio UF Mullins Lectures on Preaching BT Logarithmic functions E-journals BT Preaching Transcendental numbers USE Electronic journals E-zines (May Subd Geog) Ë (The Russian letter) E.L. Kirchner Haus (Frauenkirch, Switzerland) UF Ezines BT Russian language—Alphabet USE In den Lärchen (Frauenkirch, Switzerland) BT Electronic journals E & E Ranch (Tex.) E. L. Pender (Fictitious character) Zines UF E and E Ranch (Tex.) USE Pender, Ed (Fictitious character) E1 (Mountain) (China and Nepal) BT Ranches—Texas E-lists (Electronic discussion groups) USE Lhotse (China and Nepal) E-605 (Insecticide) USE Electronic discussion groups E2ENP (Computer network protocol) USE Parathion E. London Crossing (London, England) USE End-to-End Negotiation Protocol (Computer E.1027 (Roquebrune-Cap-Martin, France) USE East London River Crossing (London, England) network protocol) UF E1027 (Roquebrune-Cap-Martin, France) E. London River Crossing (London, England) E10 Motorway Maison en bord du mer E.1027 (Roquebrune- USE East London River Crossing (London, England) USE Autoroute E10 Cap-Martin, France) Ê-luan Pi (Taiwan) E22 Highway (Sweden) Villa E.1027 (Roquebrune-Cap-Martin, France) USE O-luan-pi, Cape (Taiwan) USE Väg E22 (Sweden) BT Dwellings—France E-mail art E190 (Jet transport) E.A. -

A Sociolinguistic Survey of the Gbe Language Communities of Benin and Togo Gbe Language Family Overview

DigitalResources Electronic Survey Report 2011-012 ® A sociolinguistic survey of the Gbe language communities of Benin and Togo Gbe language family overview Angela Kluge A sociolinguistic survey of the Gbe language communities of Benin and Togo Gbe language family overview Angela Kluge SIL International® 2011 SIL Electronic Survey Report 2011-012, March 2011 Copyright © 2011 Angela Kluge and SIL International® All rights reserved Contents Abstract 1. Introduction 2. Classification and clustering of Gbe 3. Classification of Gbe: Problems with the dialect-language dichotomy 4. Classification of Gbe as a macrolanguage with member languages 5. Classification of Gbe outside the dialect-language dichotomy 6. Sociolinguistic literature extensibility study of the Gbe language continuum 7. Summary References 2 Abstract This paper presents a tentative classification of the Gbe language varieties (Kwa language family), spoken in the southeastern part of West Africa. Given the chaining pattern of the Gbe cluster, this paper also discusses whether the individual Gbe speech varieties should be considered and classified as dialects of one larger language, or as closely related but distinct languages, or as member languages of a Gbe macrolanguage. To date no satisfying solution is available. Further, this paper serves as an introduction to the 10-volume series “A sociolinguistic survey of the Gbe language communities of Benin and Togo,” represented in a series of reports published in SIL Electronic Survey Reports: Kpési (Durieux-Boon et al. 2010), Ayizo (Hatfield and McHenry 2010), Kotafon (Hatfield et al. 2010), Xwela (Henson et al. 2010), Xwla (Henson and Kluge 2010), Ci (Henson 2010), Defi (Johnson 2010), Saxwe, Daxe, and Se (Johnson 2010), Tofin (Schoch 2010), and Gbesi (Schoch 2010). -

PDF Download

International Journal of Advanced Engineering and Management Research Vol. 2 Issue 5, 2017 http://ijaemr.com/ ISSN: 2456-3676 DIFFICULTY OF ACCESS TO SECONDARY EDUCATION AND LOCAL DEVELOPMENT IN THE COMMUNITY OF DJIDJA (WEST AFRICA) Victorin Vidjannagni GBENOU1, Expédit W. VISSIN2, Hilaire S. S. AIMADE2 1. Department of Sociology and Anthropology (University of Abomey-Calavi) 2. Laboratoire Pierre Pagney ‘’Climat, Eau, Ecosystèmes et Développement’’ (LACEEDE), Université d’Abomey-Calavi (Bénin) ABSTRACT This research has studied the problem of education and local development in the municipality of Djidja. The methodological approach adopted for this study is based on data collection, data processing and results analysis. The data processing to lead to the realization of the figures and tables which made it possible to identify the educational difficulties and to examine the place given to education in the Commune of Djidja. The results from the field surveys showed a wide range of educational problems, namely: a low level of access: 151 PPE, 19 nursery schools, and 12 CEG for 123542 inhabitants; absence of retention measures (follow-up, canteen, infirmary ...) leading to high rates of persistent drop-out (Primary: 13.15%, Secondary I: 12.66% and Secondary II: 27.35%). At the level of quality it was found: insufficient teaching materials, the lack of laboratory and a body of teachers mostly high school very low qualified (0.80% APE, 04.99% ACE, 94.21% Vacataires ) in the municipality of Djidja. Key Words: Djidja commune, education, education, local development. 1- Introduction "The resources that will make the riches of the world of tomorrow will come not from the fields, but from the factories, but from the works of the spirit." This prognosis, as set out in UNESCO's general report in 2000, reflects the need for world states to invest in education to ensure a future free from poverty and ignorance (Houedo et al.